Features

Professor Kyle Pattinson from the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences explains how brain scanning could help doctors to personalise treatment for people with chronic breathing disorders.

Ever realised you’ve forgotten your inhaler and immediately felt your breathing become more difficult? Ever wanted to walk upstairs to get something, but the thought of becoming breathless has stopped you? You’re not alone! Our brains store a phenomenal amount of information about the world, based on our past experiences. This helps us to assess situations quickly and anticipate how our bodies will respond, such as when we will become breathless. These ideas are learned and updated constantly throughout our life, and quickly adapt if we develop something like a chronic breathing disorder.

These learned ideas, or ‘priors’, are thought to not only influence our actions (such as avoiding the stairs), but can materially alter the way we perceive a symptom like breathlessness. This theory is termed the ‘Bayesian brain hypothesis’, and it explains how our priors are compared to incoming sensory information in the brain, and both pieces of information are used to create our conscious perception.

Breathlessness can be experienced by people with a wide range of conditions: those with respiratory, cardiovascular or neuromuscular diseases, as well as some people with cancer or conditions such as panic disorder. Symptoms vary, but can include hunger for air, increased breathing effort, rapid breathing and chest tightness. These breathing symptoms have been known for a long time to be influenced by psychological states such as anxiety, but also by low mood, hormone status, gender, obesity and level of fitness. However, the influence of our previous experiences and learned associations has only more recently entered into the equation.

When we have repeated or frightening exposures to breathlessness, such as an asthma attack or severe breathlessness, our brain can quickly learn and update our priors. This system is designed to help us to avoid threats and keep us safe, but generating very strong expectations (priors) about breathlessness can then exacerbate our symptoms on future occasions. What’s more, certain personailty traits such as higher anxiety, or greater body awareness may also influence this system, making some people more susceptible to developing strong expectations about their breathlessness. Once these expectations are embedded, they can be difficult to ‘un-learn’ – the brain can easily catastrophise about the potential worst case scenario, such as having another asthma attack.

Scientists at the University of Oxford are at the cutting-edge of a continually improving brain imaging technology that is being used to shed some light on what exactly is happening when we anticipate and experience breathlessness (see some examples here and here). Over the last eight years our research team has been steadily chipping away at these brain mysteries, in the hope that their findings will lead to more carefully targeted and personalised treatments for people with chronic breathlessness.

In the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, we are using high-field functional magnetic resonance imaging to look at the brain’s workings in incredible detail. This has enabled us to start uncovering the complex neural mechanisms involved in dealing with breathlessness.

The team have been exploring brain networks of breathlessness perception in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (sometimes known as emphysema or bronchitis). The most successful currently available treatment for this condition is pulmonary rehabilitation: a programme of exercise, education, and support to help people with chronic breathing problems learn to breathe more easily again. This type of rehabilitation does not influence physical lung function. That means that it must instead work by helping people to change their learned priors, which make them overestimate the threat of breathlessness (we’re back to those stairs again).

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, we have confirmed that the people who had benefitted from this rehabilitation programme had both higher initial brain activity and greater rehabilitation-induced changes in parts of the brain linked to body symptom evaluation and emotion – the insula and anterior cingulate cortex. They are now working towards studies that can help to increase these changes in breathlessness expectations, and to identify which people in particular are most amenable to the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation. This was the focus of our recently published study, and will help to better understand how personalised therapy may be designed for each individual.

Treating the lungs AND the brain

Clearly there can’t be a ‘one size fits all’ approach to treating debilitating perceptions of breathlessness. Current attempts to treat the complexity of chronic breathing problems have been somewhat scattered, and we must now work towards understanding the individual ‘lived experience of breathlessness’ to lead us to more carefully nuanced interventions. The different factors at play in breathlessness all need to be targeted as part of a comprehensive treatment programme: What are the brain mechanisms at work in learned expectations? How do anxiety, stress and low mood impact on breathlessness? How closely are the observable physical symptoms actually linked to lung function? Imagine the discomfort that could be reduced and quality of life that could be improved, not to mention the money that could be saved (breathlessness due to COPD costs the NHS more than £4 billion per year), if breathlessness were approached in a more holistic way.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is just one in a raft of potential behavioural and drug therapies that could be used to ease the often crippling fear of breathlessness. Only 35% of people who are prescribed pulmonary rehabilitation actually take it up (for a variety of reasons, including not being able to get out to the venues where it is run); and only 60% of those who take it up actually benefit. Therefore, more research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms of breathlessness perception, and develop different treatments that would be suitable for different people. It is the details we are gleaning about the incredibly complex brain mechanisms of symptom perception that will equip us to design more successful treatment options for those whose symptoms do not match their lung function, to bring breathlessness back under control.

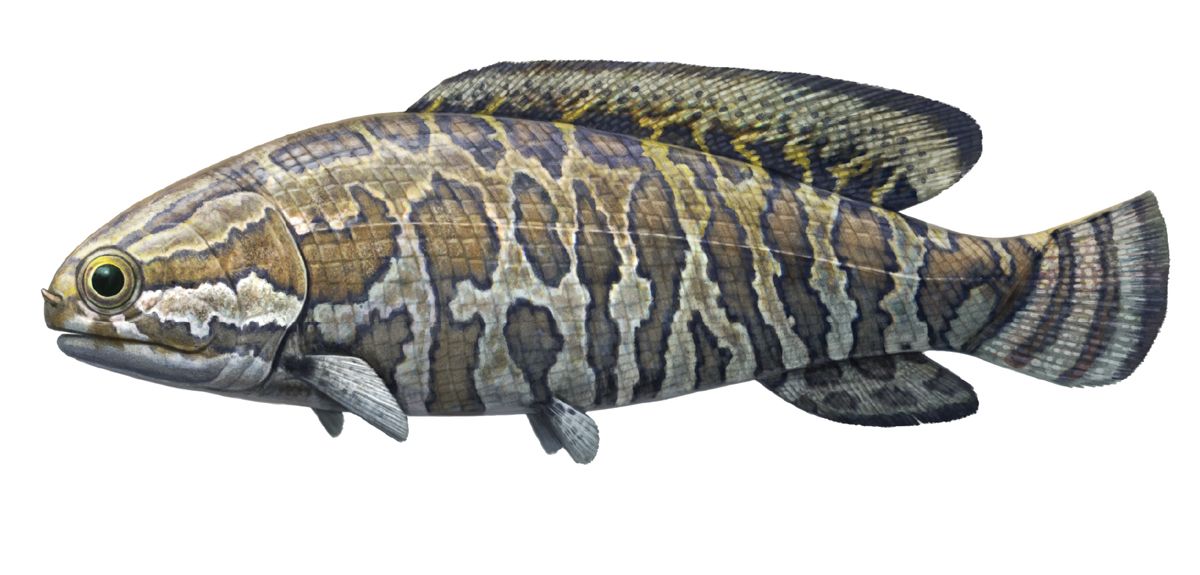

Oxford researchers have conducted a new analysis which reveals a surprising twist in the tale of how fish evolved.

The ray-finned fishes are the most numerous group of backboned animals. There are tens of thousands of different ray-finned species, from angelfish to zebrafish, making up 99% of all species of fish, and 50% of all vertebrates. They are useful to humans as a source of food, and sometimes even as pets, but they are also our distant cousins. We share a common ancestor, deep in evolutionary history. We know a lot about how the other major group of vertebrates, lobe-finned fishes, evolved as they began to move onto dry land, giving rise to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals, including humans. However, the early evolution of the ray-finned fishes’ side of the family tree is not so well understood.

Now, an international team including researchers from Oxford University’s Department of Earth Sciences have discovered a new piece of the puzzle. They looked at polypterids, bizarre fish which live in African freshwaters. Led by Dr Sam Giles from the University of Oxford, they used CT scanning to take a fresh look at the ancestors of modern polypterids, fossilised 250 million years ago.

Although polypterids are technically ray-finned fish, they have a curious combination of features, including thick scales, lungs and fleshy fins, which make them look very ancient - they have been referred to as “dinosaur fish”. They are so strange that scientists didn’t work out that they were ray-finned fish for more than a century after they were discovered. The polypterids seem to be out of place in time, more primitive in evolutionary terms than fossilised ray-finned fish from millions of years ago.

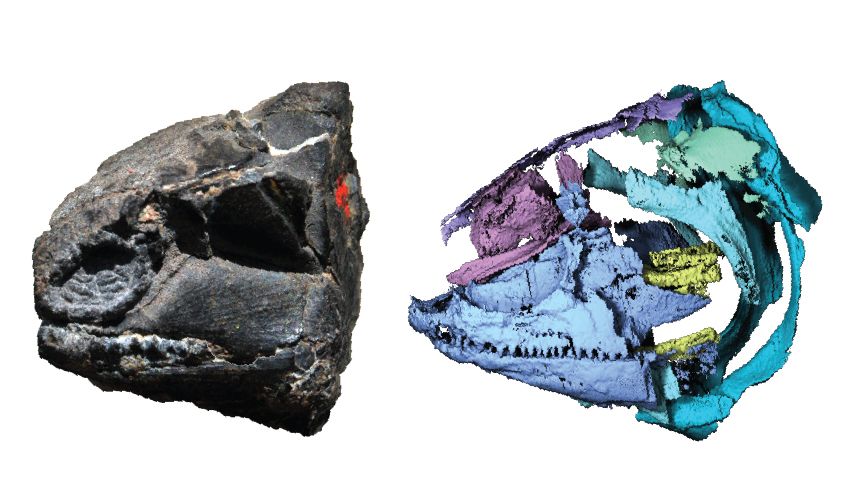

250-million-year-old fossilised head of a polypterid beside a digital visualisation of its skull

250-million-year-old fossilised head of a polypterid beside a digital visualisation of its skullImage credit: Andrey Atuchin

However, the researchers discovered that the “dinosaur fish” aren’t as primitive as they seem. Looking at modern polypterids alongside fossils of their ancestors, it appears that, in fact, they developed some of their odd characteristics later in time.

“Polypterids appear to have undergone several reversals in their evolution, which has clouded the view of their position in the fish family tree,” Dr Giles explained. “It’s as if your brand-new smartphone came with a rotary dialler and without Wi-Fi; we know it’s the latest handset, but its characteristics might lead us to think it’s an older model.”

Now we understand these outwardly “primitive” characteristics for what they were, the polypterids, and their position in the lineage of ray-finned fish, start to make more sense.

“With this new analysis, we were able to iron out a lot of the wrinkles in our understanding of the sequence of evolutionary events,” Dr Giles reflected. “These results change our understanding of when the largest living group of vertebrates evolved, and tell us that ray-finned fishes dominated the seas following a major mass extinction that eradicated their closest rivals.”

“Analyses like these are powerful tools, and go to show that palaeontology doesn’t always rely on the discovery of new fossils; re-examination of old fossils using new techniques is just as important for revitalising our understanding of vertebrate evolution.”

The full paper was published in Nature as “Early members of ‘living fossil’ lineage imply later origin of modern ray-finned fishes”: DOI: 10.1038/nature23654.

Cutting-edge science research in gleaming laboratories. Undergraduates defending their essays to a world expert in the field in a tutorial. The tortoises who take part in an annual inter-college race.

This diverse group of people – and reptiles – are the stars of a new exhibition of photography by Magnum photographer Martin Parr.

Martin Parr: Oxford is a free exhibition that forms part of Photo Oxford 2017 (8 – 24 Sept) and will run from 8 September to 22 October 2017 at the Weston Library.

As part of the commission, Mr Parr was given access to many of the University’s most iconic buildings and events. He told Vice that he enjoyed the project.

“[Oxford] has everything. It has tradition, it's on the cutting edge of research, it's evolving yet staying still,” he said.

“It was meant to be one year's project; it became two years. I don't know how many trips I made there, 50 or 60. I could have gone on for ten years. Once you start digging, you realise the complexity of a place.”

‘Martin Parr has brought his unique viewpoint to the University and we are delighted to be able to show some of his images opening up Oxford at this free exhibition in the Weston Library,’ says Richard Ovenden, Bodley’s Librarian.

‘Martin strongly supported the Bodleian’s campaign to acquire the archive of William Henry Fox Talbot, who made the first photographic journey to Oxford in the 1840s, and I’m sure this new collection, looking at the many different aspects of Oxford life will be of huge interest to Martin’s fans, local residents, visitors and alumni alike.

'This is a rare opportunity to see work of a brilliant photographer who normally only exhibits at larger international galleries.’

A one day symposium featuring talks by the Photo Oxford 2017 artists will run at the Weston Library on Thursday 7 September. The publication OXFORD Martin Parr, by Oxford University Press, is available to pre-order online.

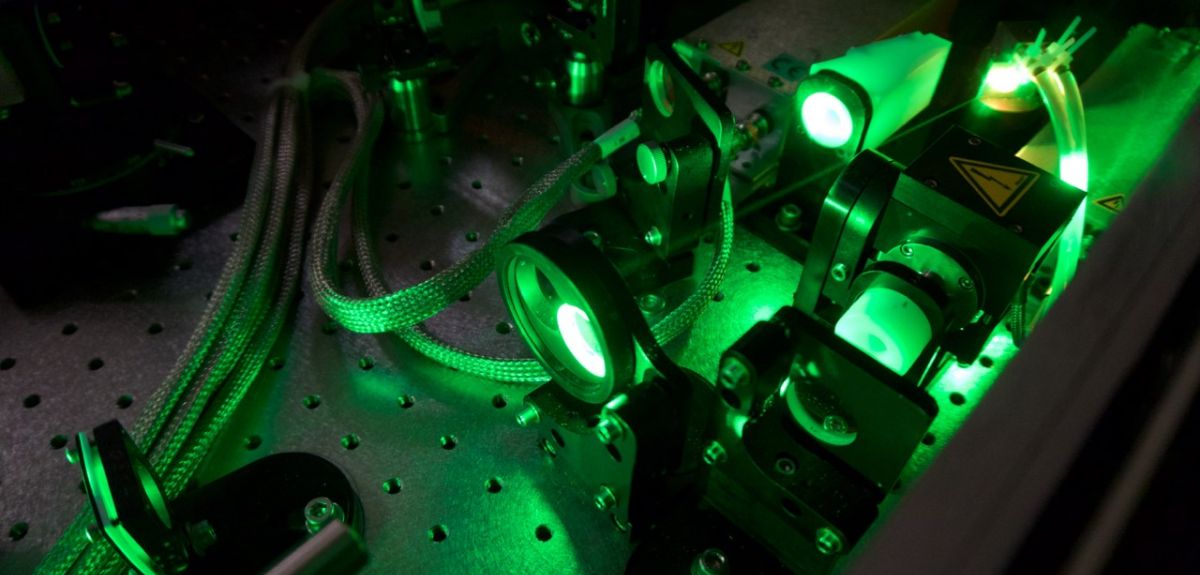

Simon Hooker is a Professor of Atomic and Laser Physics at the University of Oxford, and Chris Arran and Robert Shalloo are two of his graduate students. They discuss the group's work on developing plasma accelerators for real-world applications.

In our group at Oxford's Department of Physics, we combine high-intensity lasers and plasmas to build extremely compact particle accelerators. Our recent experimental results, published in Physical Review Letters, demonstrate a new way to do this - bringing us a step closer to seeing these accelerators widely used in commercial and medical applications.

When we think of particle accelerators - machines which accelerate particles such as electrons and protons to almost the speed of light, we tend to think of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, which is the largest machine ever built at 27 km in circumference. But of the more than 30,000 particle accelerators in operation worldwide today, fewer than 10% are used for scientific research and only 1% specifically in high energy particle physics. So what are the rest used for?

Particle accelerators have been used to investigate new fuel sources and study holy relics - but the vast majority are used in medicine and industry. In medicine, accelerators are used for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, to produce high quality beams of X-rays, and for advanced medical imaging. In industry, accelerators are an integral part of processing a broad range of products, from treating foodstuffs for increased shelf life to microelectronics inside smartphones. In fact, it is estimated that every year accelerators treat over £350 billion worth of products. But almost all of the accelerators used for these applications rely on technology developed nearly a century ago.

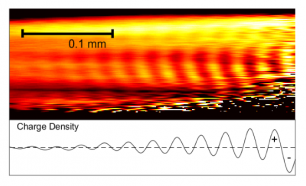

In recent years, scientists around the world have been working to develop new accelerators powered by the interaction of very intense laser pulses and plasmas. In these "laser wakefield accelerators" an intense laser pulse is fired into a gas, which ionizes it to form a mixture of negatively charged electrons and positively charged ions, at temperatures approaching a million degrees. As the laser pulse travels through the plasma it pushes the plasma electrons out of its way, setting up a "plasma wake" behind it - just as a boat moving across a lake creates a wake. The alternation of positive and negative charge densities within the plasma wake sets up huge electric fields, equivalent to a voltage difference of 10 million volts across the diameter of a human hair. These intense fields can be used to accelerate charged particles to high energies in a distance hundreds to thousands of times smaller than in a conventional particle accelerators, dramatically shrinking the size and cost.

Laser-plasma accelerators have already been used to generate electron beams with similar energies to that used in synchrotron light sources - like the Diamond Light Source near Oxford, but in an accelerator stage only a few centimetres long, rather than in a stadium-sized machine. However, the lasers used could only fire a few times per second, severely limiting the applications of these compact accelerators.

We recently proposed a new approach, called the "multiple-pulse laser wakefield accelerator" (MP-LWFA) which could increase the repetition rate of laser-plasma accelerators by a factor of a thousand.

The idea is to drive the plasma wake with a train of lower energy laser pulses, rather than with a single, high-energy pulse. If the pulses are spaced correctly they "kick" the plasma in time with the plasma motion driven by the earlier pulses, in just the same way that repeated, well-timed pushes of a swing result in a large amplitude oscillation. This change of approach allows very different types of laser to be used, which can deliver thousands of pulse trains per second and with high "wall-plug" efficiency. The ultimate goal is to generate synchrotron-like electron and X-ray beams from a laboratory-scale device.

A snapshot of a laser wakefield produced in our experiment. The image shows the wake created behind a laser pulse travelling left to right, leaving behind areas of alternating positive and negative charge.

Recently we demonstrated these ideas in an experiment performed at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory near Oxford. In that work, we fired a train of laser pulses into a plasma and measured the size of the plasma wake which was driven. We found that, just as expected, the strength of the wake was maximized when the laser pulses were separated so that they kicked the plasma in time with the plasma oscillation driven by the earlier pulses. In contrast, if the pulse separation was mismatched to the plasma oscillation then the plasma wake disappeared. Detailed analysis showed that the experimental data was in very good agreement with our theoretical models, confirming that we have a clear understanding of the physics at play.

Having demonstrated the concept, future work will be aimed at generating electron beams and working with experts in laser physics to develop an architecture for a new generation of compact laser-driven accelerators with properties useful for real-world applications.

If you'd like to read more about the experiment you can find a general synopsis article here and you can find out more about our group and other areas of research here.

An Oxford classicist has worked with Italian secondary-school students to create an award-winning new exhibition in Sicily, cataloguing stone inscriptions from the Roman period.

Dr Jonathan Prag, of Oxford’s Faculty of Classics, worked in collaboration with students from the Liceo Artistico Statale M.M. Lazzaro in Catania, Sicily, to create the exhibition, entitled ‘Voci di Pietra’ (‘Voices of stone’).

The exhibition, which is housed in the Norman castle that now serves as Catania’s civic museum, features artefacts between 1500 and 2500 years old, including funerary inscriptions, sculptures, and fragments of buildings, as well as video installations created by the students.

These texts are important because they are contemporary documents. They very often provide information about specific events and private individuals, of a type that is not recorded elsewhere. Inscriptions provide a vast body of information on religious beliefs, naming practices, language, and much more.

Dr Jonathan Prag

Catania was originally a Greek city, and was re-founded as a Roman colony, so the inscriptions are in a mixture of Greek and Latin. The inscriptions provide valuable information both about economics and diplomacy in ancient Catania, and about the private lives of individuals in the city.

One intriguing item is a funeral inscription for a Jewish Roman citizen called Aurelius Samohil (i.e. “Samuel”), from 383 AD (pictured below). This is written in a mixture of Latin and Hebrew, and constitutes the longest Latin text from the ancient Jewish diaspora in the Roman world. The inscription contains a triple warning to posterity not to break into the tomb where Aurelius Samohil and his wife Lassia Irene were buried. This and other texts suggest there was a strong Jewish community in Catania.

The students, who won a prize for their work from the Italian Ministry of Education, worked on the exhibition between 2015 and 2017. They were involved in locating, cleaning and recording the exhibits, as well as presenting them in novel ways – for instance, they designed a reconstruction of a columbarium, a type of Roman tomb. They will use the prize to visit Oxford this autumn.

“The enthusiasm and engagement of the students went well beyond anything I had seen elsewhere or expected,” said Dr Prag, who undertook the project as a Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Oxford Research Centre for the Humanities (TORCH). “They did not have a background in classical studies, but they brought serious artistic flair and a very high level of observation and skill. The end result – a highly professional permanent exhibition – is certainly beyond my original expectations.”

He adds that one of his favourite exhibits is “the rather wonderful video of a very elderly retired stone mason from Catania whom the students found and interviewed, in order to learn about the actual practicalities of engraving on stone”. The students used what they learned from him to create their own inscription as a record of the exhibition.

Dr Prag is now working on a larger project called I.Sicily, which aims to create an online archive of Sicilian inscriptions, reflecting the diverse languages spoken on the island in ancient times.

- ‹ previous

- 92 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators