Mapping the Moon: the world’s first lunar atlas goes digital

In 1647, a self-taught astronomer and brewer from Gdańsk changed the way humanity saw the Moon by creating the first detailed map of the lunar surface. Now, nearly four centuries later, the Bodleian Libraries have brought Johannes Hevelius’s Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio ('Selenography, or a Description of the Moon') into the digital age – allowing anyone, anywhere, to explore the world’s very first lunar atlas.

Portrait of Johannes Hevelius. Date: 1646 – 1649. Credit: Rijksmuseum.

Portrait of Johannes Hevelius. Date: 1646 – 1649. Credit: Rijksmuseum.Selenographia was pioneering in its accuracy, showing that Moon’s surface was far from a blank canvas, but a mosaic of craters, valleys, and mountains. The complete atlas is made up of 111 plates and engravings, showing the Moon in every phase, besides a composite map depicting all of the Moon’s features as if lit from the same direction, which became the model for later lunar maps.

This remarkable artefact is of high interest to astronomers, lunar enthusiasts, and historians of science worldwide. Up to now, those wishing to view it would have to come to the Bodleian in person and arrange for the item to be brought out specially. But now a fully-digitised, open-access version is available through Digital Bodleian, the Library’s showcase platform for digitised collections, for anyone to admire, anytime – even from the comfort of their own home.

Judith Siefring, Head of Digital Collections Discovery at the Bodleian, says: ‘The Bodleian is committed to democratising access to its really amazing collections, and digitising as many manuscripts, archives, and rare books as possible forms a large part of that. Around 75% of those who use Digital Bodleian are based outside the UK, demonstrating that we are serving an international audience.’

A remarkable object from a remarkable man

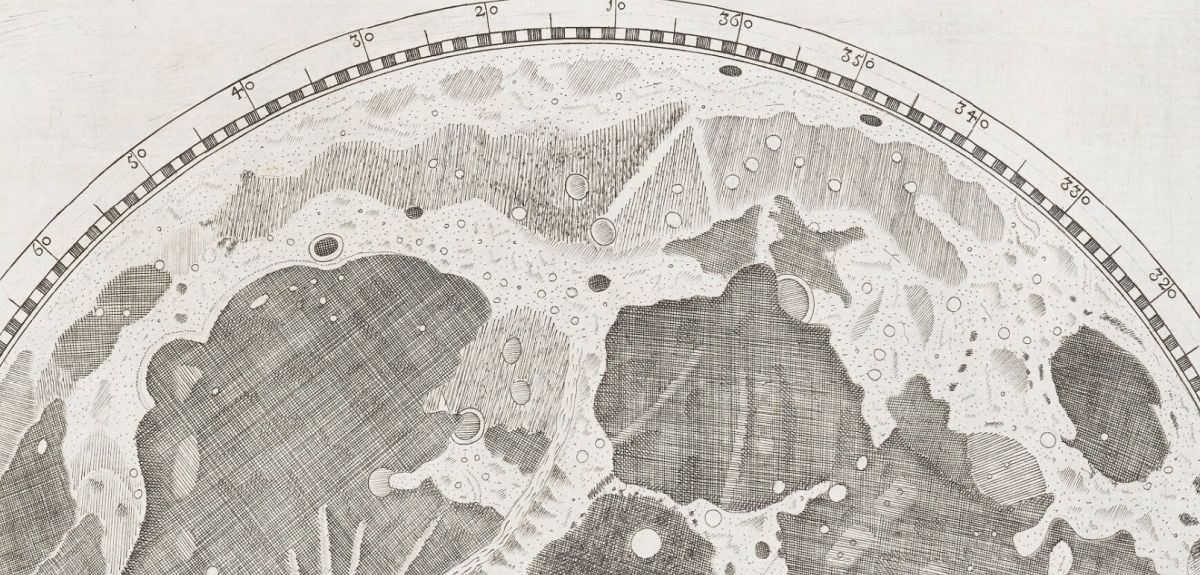

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12.

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12. Producing a lunar atlas was one of Hevelius’s first major endeavours, the other being a catalogue of 1564 stars. Over five years, he meticulously drew the Moon each night from observations by eye and through his telescopes, then engraved his observations in copper the following morning.

‘Considering the equipment he was using, the level of detail of the map is mind-boggling,’ adds Malgorzata. ‘Rudimentary maps of the Moon already existed, but none as detailed as this, and none in the form of an atlas. Hevelius took it upon himself to name various aspects of the terrain, indicating that he discovered many details that were not known about previously.’

Many of the names Hevelius gave to lunar characteristics are still used now (such as ‘Alps’ for lunar mountains), and a large crater on the edge of the Ocean of Storms also bears his name today. When the volume was published in 1647, it brought Hevelius fame and prestige as an astronomer, but perhaps the greatest testament to Selenographia is that it stood as the ultimate lunar reference manual for over a hundred years.

Digitising a treasure

Photographer Ellie Harris in the Bodleian Imaging Studio.

Photographer Ellie Harris in the Bodleian Imaging Studio.The project to digitise Selenographia took shape after the presentation copy was displayed for a group of visiting directors of Polish museums and art galleries. Through collaborations between the Bodleian, the Polish Ball, and the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building, a private donor came forward to fund the digitisation. Malgorzata recalls: ‘Mr Karol Sieniuc was so impressed by the Bodleian’s collections and how it strives to make them available to everyone, that he did not need much persuasion to sponsor the digitisation of a Polish treasure that is Selenographia.’

Selenographia was digitised in the Bodleian Libraries’ dedicated studio, one of the country’s leading imaging facilities. This is equipped with high-resolution cameras and bays tailored to digitise different types of material, from papyrus and maps, to manuscripts and rare books. Over the course of a week, the atlas was captured in just under 800 images at 600-dpi resolution, each checked and aligned using specialist software, then linked to bibliographic data before publication online. The resulting digital version allows users to leaf through Selenographia virtually and zoom in to explore even the finest engraved details, revealing the Moon as Hevelius first saw it nearly four centuries ago.

Connecting communities

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12.

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12. ‘Digitising collections fulfils many key purposes,’ says Judith. A major one is preservation, of course. Interestingly, much of Hevelius’s observatory, instruments, and books were destroyed by a fire in 1679, and the original copper plate used to print Selenographia was sold after his death and turned into a teapot. ‘Another key purpose is engaging diverse audiences with our collections in new ways, and opening up the knowledge they contain to the world,’ adds Judith.

Digital Bodleian has already made over 1.3 million images of rare manuscripts, maps, and printed works freely available online. Previous major initiatives have included partnerships with the Vatican Library (Greek and Hebrew manuscripts and early printing) and with the Herzog August Bibliothek (medieval Manuscripts from German-speaking Lands), both generously funded by the Polonsky Foundation. Other projects have included Literary Manuscripts (funded by the Tolkien Trust) and Education & Activism: Women at Oxford 1878-1920, a collaboration with several Oxford colleges.

You can find the digital version of Selenographia here.

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools