Features

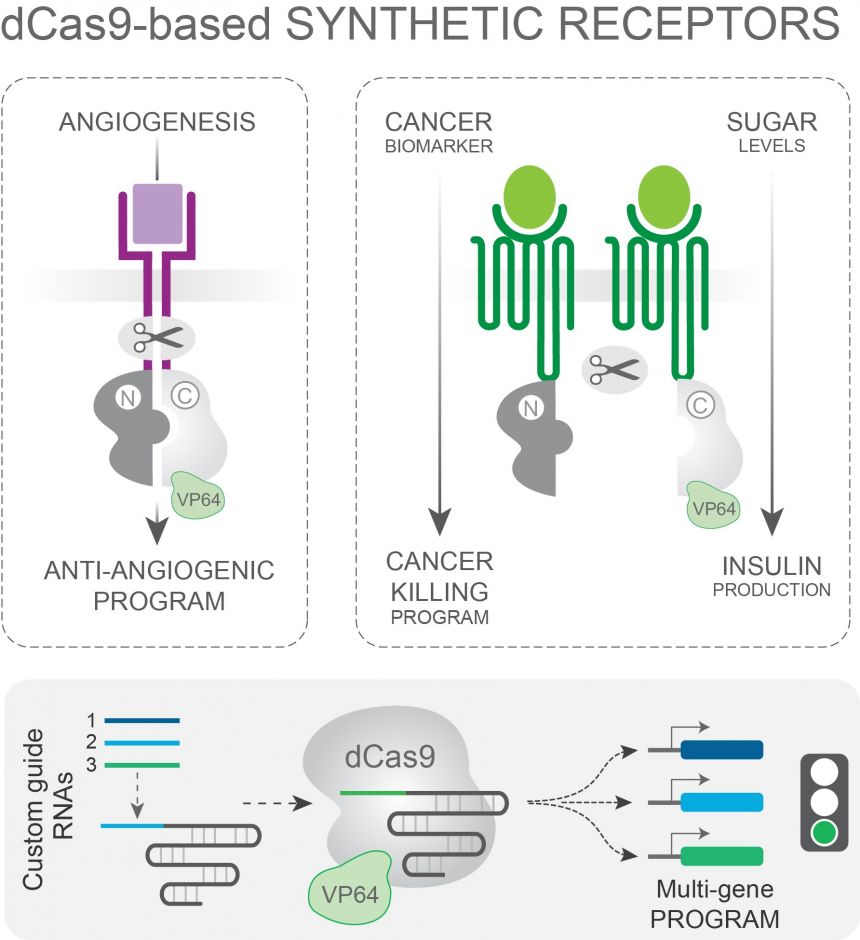

Researchers at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine have developed a new platform based on the revolutionary CRISPR/Cas9 technology, to alter the way human cells respond to external signals, and provide new opportunities for stopping cancer cells from developing.

Cells are constantly monitoring the environment around them and are programmed to respond to molecular cues in their surroundings in distinct ways – some cues may prompt cells to grow, some lead to cell movement and others initiate cell death. For a cell to remain healthy, these responses must be finely balanced. It took evolution over two billion years to tune these responses and orchestrate their interplay in each and every human cell. But what if we could alter the way our cells respond to certain aspects of their environment? Or make them react to signals that wouldn’t normally provoke a reaction? New research published by scientists at the University of Oxford takes cellular engineering to the next level in order to achieve just that.

In a paper published in Cell Reports, graduate student Toni Baeumler and Associate Professor Tudor Fulga, from the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, have used a derivative of the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to rewire the way cells respond to extracellular signals. CRISPR/Cas9 frequently makes the headlines as it allows medical researchers to accurately manipulate the human genome – opening up new possibilities for treating diseases. These studies often focus on correcting faulty genes in crops, livestock, mammalian embryos or cells in a dish. However, not all diseases are caused by a defined error in the DNA. In more complex disorders like diabetes and cancer, it may be necessary to completely rewire the way in which cells work.

Cells are exposed to thousands of different signals – some they will have encountered before, while others that are entirely new. Receptors that sense these signals form one part of a complex modular architecture created by the assembly of building blocks like in a Lego design. It is the precise combination of these ‘Lego bricks’ and the way in which they are built that dictates how a cell responds to a given signal.

Changing the way cells interact with each other

Changing the way cells interact with each otherImage credit: Tudor Fulga

Rather than using the traditional CRISPR/Cas9 system, the team used a version of the Cas9 protein that cannot cut DNA. Instead, it switches on specific genes, depending on the guide RNA (navigation system) it is associated with. Using this approach, the researchers altered the Lego bricks to build a new class of synthetic receptors, and programmed them to initiate specific cascades of events in response to a variety of distinct natural signals.

So could this innovative cellular tinkering improve human health? To answer this question, the team sought to re-program the way in which cancer cells respond to signals that drive the production of new blood vessels (a key step in cancer development). Using a rationally designed synthetic receptor they created in the lab and delivered into cells in a dish, the team converted a pro-blood vessel instruction into an anti-blood vessel response. To test the limits of the system, they then went on to engineer a receptor complex that responds to a signal enriched in the tumour environment by eliciting simultaneous production of multiple ‘red flags’ (effector molecules) known to attract and instruct immune cells to attack cancer. These initial experiments in the lab open up a whole range of possibilities for next-generation cancer therapy.

The system also has potential applications for other systemic diseases, like diabetes. To demonstrate this potential, the team engineered another receptor complex that can sense the amount of glucose in the surroundings and prompt insulin production – the hormone that takes glucose up from the blood stream. In people with diabetes, this mechanism does not work correctly, leading to high levels of glucose in the blood. While a long way from the clinic, the work suggests that this technology could be used to rewire the way that cells in the body function.

The ability to edit the human genome has transformed the way scientists approach some of our biggest medical challenges. With this new technique developed in Oxford, the team hopes that genome engineering does not have to be limited to correcting DNA faults but altering the way that cells work – regardless of the root cause of disease.

Understanding when and how genes first came together to form genomes is a fundamental puzzle in the study of the origin of life. Genes are naturally selfish, and yet, life started with cooperation between genes. So, why did these first living molecules sacrifice their selfish interests to form genomes?

Sam Levin, a DPhil student in Oxford’s Department of Zoology, discusses his new study: 'The evolution of cooperation in simple molecular replicators’, written in collaboration with Professor Stuart West, which addresses this very question.

Contemporary life forms, from bacteria to bonobos, are made up of genomes. A genome is a collection of replicating units, or genes, which specialise on different aspects of making an organism. Some genes focus on making an eyeball, and others on producing a lung. We don’t think of these genes as individuals in their own right - they are simply parts of the larger whole - the organism.

The origin of the first genomes billions of years ago required gene cooperation, but life itself started with simple, independent genes, or replicators. These replicators were ‘naked molecules’, which were capable of little more than making copies of themselves. Early replicators were individuals in their own right. They competed, with replicators that were better at making copies of themselves, out-competing those that were less fit.

At some point, before the last common ancestor of all living things, independent replicating molecules - naked genes, had to come together to form the first genomes. In the process, they subjugated sacrificed their own interests (reducing their own replication rates, helping copy other replicators) to become part of the larger whole, or genome.

In our paper, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, we use mathematical models to show why these primitive life forms might have cooperated, and reveal the link between their behaviour and that of birds, bees, microbes and humans.

Offspring copies sticking around and parent copies surviving both increase ‘relatedness’ between replicators (sharing the same genetic sequence). This shows that the forces that favour cooperation are the same across the tree of life.

The puzzle of cooperation

Darwin (1859) showed us that, all else being equal, we expect selfish individuals to outcompete cooperative ones. Imagine a soup of replicators in the primordial sea, where replicators act cooperatively (reducing their own replication rate) to help copy others. Suppose a mutant arises, which, rather than help others, selfishly copies itself. This mutant reaps the benefits of others being cooperative, but doesn’t incur any cost of helping others. This mutant will outcompete the rest, sweep through the population, and cooperation will disappear. What, then, could explain the continued cooperation between replicators?

We used simple mathematical models of evolution to analyse this question. Previous work by Paul Higgs and colleagues using simulations suggested that replicator cooperation could be explained by replicator copies staying nearby to each other (limited diffusion). When this happens, because copies are essentially clones of their parents, cooperators find themselves near other cooperators, and selfish molecules find themselves near other selfish molecules. Cooperators reap the benefits of cooperation, and selfish molecules have no one to exploit. Soon there are only cooperative molecules and no selfish ones.

Instead of using complex computer simulations, we used simple, pen and paper mathematical models. We found several results. First, when replicator copies stay near each other, this always leads to cooperation. Although it leads to cooperators helping other cooperators, it also leads to cooperators competing with other cooperators, instead of competing with selfish individuals. We found that these two effects exactly cancelled each other out. Instead, an additional biological feature of replicators is necessary for cooperation to evolve: the survival of replicators after they copy themselves (overlapping generations). This also leads to like-individuals being together, but it reduces the negative impact of competition. We showed that the survival of copies after reproduction and offspring copies remaining nearby, are both necessary to favour cooperation at the start of life.

A common thread in the tree of life

Surprisingly, the simple models that we used are the same as those used to understand cooperation across the tree of life, from bacteria to humans. Cooperation didn’t just happen in replicators, it’s everywhere in nature, from cooperatively breeding birds to complex ant colonies. The problem of cooperation in higher organisms has long been understood using the theory of kin selection, developed by Bill Hamilton in 1964 and popularised by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene. Organisms cooperate due to shared genes. A bird can get copies of its genes into the next generation by reproducing itself, or by helping a relative, who shares genes, to reproduce. In other words, genes acting selfishly (getting copies of themselves to the next generation) leads to organisms appearing cooperative. Relatedness (shared genes) favours cooperation.

Our work shows that the same kin selection approach used in birds and bees can be used to understand the first replicators. Offspring copies sticking around and parent copies surviving both increase ‘relatedness’ between replicators (sharing the same genetic sequence). This shows that the forces that favour cooperation are the same across the tree of life, from early human societies to the origin of life.

This is the latest article in Bethany White's Artistic Licence series.

Donald Trump invented a new word this summer. “Covfefe!” he tweeted, and we were all a bit confused.

But could Trump’s covfefe one day find its way into the dictionary?

Simon Horobin, Professor of English Language and Literature at Magdalen College, has spent years studying the English language, and he thinks that technology is changing how we use it.

On social media, e-mail and WhatsApp, speed is important. This means we often use abbreviations, make new words up entirely, or fall victim to the typo.

But, Professor Horobin says, in some ways this doesn’t actually matter. “In certain media, it’s almost expected and understandable.”

And, for what it’s worth (FWIW), there are a few examples of internet slang creeping into the dictionary. In case you missed it (ICYMI), both FWIW and ICYMI made it into the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016.

So did ‘listicle’—which, for those of you who don’t live on Buzzfeed, is not a sea creature but “a journalistic article or other piece of writing presented wholly or partly in the form of a list.”

Professor Horobin argues that technology and social media can make these new words more visible. “This kind of slang has always been around, but the difference is that now it spreads much more quickly,” he explains.

But who is in charge? Who decides what ends up in the dictionary? The answer might surprise you.

To decide what goes in a dictionary, editors analyse a huge amount of data, including printed material, websites, social media feeds, forums, blogs, and e-mails. They look at how often words are used, and how people are using them.

This is because dictionaries are descriptive rather than prescriptive—they don’t tell us what to do, they just describe what we’re already doing. This means that, ultimately, new words and spellings come from us—the users.

So does this mean covfefe is going to worm its way into the OED?

Well—no. Compiling the dictionary is a complex process. “It doesn’t mean that every time you fire off an e-mail, you create a word,” Professor Horobin says. “Or that covfefe is going to appear in the dictionary.”

And while spelling mistakes are often more expected on social media, this doesn’t mean they go unnoticed.

“The internet has also given a new lease of life to correcting people,” Professor Horobin says. “Just look at #spellingfail on Twitter. There are a lot of people policing other’s mistakes.”

Ultimately, Professor Horobin says, “it’s still going to be important to get a good grip of standard English.”

Mr Trump might have covfefe to himself for now. But technology is still changing the English language in ways we haven’t seen before.

“The technological revolution means that spelling is much more fluid and there’s a different attitude to correctness,” Professor Horobin argues. “English is changing very rapidly.”

So you’d better keep practising your spelling—but you can also keep on abbreviating, inventing, and firing off misspelt tweets. In fact, you never know—as you do, you could be creating the English of the future.

The challenge of providing a rapid response to environmental disasters as varied as flooding, drought, illegal logging and oil spills is the focus of two new projects in which the University of Oxford is a key partner. Dr Steven Reece, data processing and machine learning lead at Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science explains how the project will work in action and the role that machine learning technology will play in it.

Preparing for a potential environmental threat is highly challenging and when it comes to identifying hazards, some data can be more useful than others.

Compared to other forms, satellite data, can quickly recognise small changes on the surface of the earth or sea that may be indicators of a larger problem in the making. For example, a new ‘hole’ appearing in a forest can provide evidence of illegal logging, or a slight colour change in crops may show the early effects of drought. Combining data from these images with other sources has the potential to create powerful information for governments and other actors.

Satellite imagery is very useful for quickly generating independent data from a wide variety of events on the earth as they unfold. The difficulty is how to organise and process this vast quantity of data and to combine it with other insights from the earth’s surface so that it can be used to inform decision-makers in the most effective way. There may also be gaps in the data, or some of it may be unreliable, and this is where machine learning technology can be really useful.

Machine learning is having a positive impact on many walks of life, supporting evidence-based decision making across a wide range of different application domains, and truly ground breaking data-centred solutions to key societal problems.

The Oxford University Department of Engineering Science are world leaders in the field. Our machine learning solutions, include tools that are capable of automating and processing large quantities of data from satellite images. This specialist knowledge will be key to a new international collaboration that will use machine learning enabled satellite imagery to make a real difference to people’s lives; improving emergency response to environmental disasters in Malaysia, Ethiopia and Kenya.

UK Space Agency funded projects led by the Satellite Applications Catapult and Airbus Defence and Space will provide a more-timely, accurate and detailed understanding of an environmental crisis than is currently available. The data gathered will be used as a starting point to create information for key decision makers in countries affected by environmental disasters, so that they are able to intervene as early as possible to protect local people and the planet.

Both projects: Earth and Sea Observation System (Malaysia) and Earth Observation for Flood and Drought Resilience in Ethiopia and Kenya, are supported through the UK Space Agency's International Partnership Programme and have attracted a total investment of £21 million.

The objectives of the work are directly relevant to many of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals:

In Malaysia we will be working with government agencies to tackle flooding, oil pollution and illegal logging, all of which pose serious social and economic threats to Malaysian people. Monsoon flooding is a major annual issue, and the project aims to enable evacuation plans and flood defences to be activated much faster. It will also generate data that will help the authorities to quickly identify and track oil leaks from shipping which are causing irreparable damage to Malaysia’s mangrove swamps, and to locate areas where illegal logging is taking place.

In Ethiopia and Kenya the focus will be on creating an improved understanding of flood and drought risk, thus helping to build local people’s resilience to these natural disasters and alleviate poverty. The intention is to use the same data to provide an emergency response where needed and to help develop longer-term strategies and solutions to drought and flood. In Kenya the project will also be generating tools to support the micro-insurance market, which is of key importance to farmers who have little or no access to insurance, by providing independent data about crop damage to verify farmers’ claims.

Our software can reconcile inconsistent data, filter out unreliable sources, and integrate information derived from other sources such as social media. It is even able to interpolate what may lie in the data ‘black spots’ between known observations, thus ‘filling in the gaps’ in the overall picture.

In collaboration with several other partners with different types of expertise, we will be bringing our specialist knowledge to bear on the real-world problems identified in Malaysia, Ethiopia and Kenya, and working out how they can be applied most effectively in these different contexts. In the drought-response work in Ethiopia and Kenya, for example, our engineers will be working with colleagues from the School of Geography and the Environment who specialise in hydrology. We will work together with partners from industry, to investigate how to use machine learning to integrate data from satellite imagery of crops with information of both surface and subterranean water resources. Combining views from above and below in this way is more powerful than looking at each one individually, and will create a much more accurate early warning of drought.

We hope that the lessons learned from this work will be used to better understand environmental threats in other areas of the world, and prevent their impact in the future.

There are over 6,000 languages spoken in the world. But did you know that, like the Indian elephant and the Bengal tiger, some of them are in danger of dying out?

From Dusner (three speakers) to Kelabit (five thousand) to Yiddish (1.5 million), these languages are sprawled across the globe, but they all have one thing in common: unless we act soon, they could become extinct.

Researchers at Oxford University are meticulously studying these languages. And Dr Johanneke Sytsema, who has organised a popular seminar on endangered languages, thinks there could be a novel way to keep minority languages alive: social media.

“Social media could help save a language,” Dr Sytsema says. “Because young people text each other how they speak, even if they don’t know how to spell it.”

Minority languages are often at risk of being drowned out by the louder voices of the bigger languages, which are spoken at school and in the media. But, with social media handing control over to the users, the advent of Facebook and Twitter might just have the reverse effect.

Dr Sytsema has first-hand experience: she speaks Frisian. Frisian, spoken in a province in the Netherlands called Friesland, has 350,000 speakers. Interacting with her own language has given Dr. Sytsema food for thought about how languages could be saved in the future.

“In Friesland, young people who don’t learn much Frisian writing at school send each other messages on social media in Frisian,” she says. In this way, a new generation of Frisian speakers keeps the language alive.

But how do languages become endangered in the first place?

“6% of the world’s population speak 94% of the world’s languages,” Dr. Sytsema explains. “That means that many of these languages only have a handful of speakers.”

But it’s not just a small number of speakers that makes a language endangered. Some languages were once widely spoken, but lost speakers over time. This can happen for many reasons.

“It can be for political reasons - governments decide that only one language can be spoken in schools, for example. Or people move away from their home and lose their language, or communities are broken up.”

Tweeting and texting in Frisian (or Sorbian, or Breton) is not enough in the long-term, though. Dr Sytsema says there are many other things we need to do.

“Government policy is important,” she says. “To support the language, provide teaching in that language, and subsidise radio, television, and printing.”

If we do all of these things, Dr Sytsema argues, we can preserve the thousands of languages that people are chattering in across the globe.

But there’s an (endangered) elephant in the room. Why is a language worth saving in the first place?

Dr Sytsema is unequivocal. It’s vital: because, like our wildlife, our languages are natural creations.

“Natural beauty needs to be protected. Once languages die, you don’t get them back, because they’ve grown over thousands and thousands of years,” Dr Sytsema explains.

“Every language has its own beauty. And that’s why it’s so important.”

You can listen to some Frisian for yourself by watching a weather forecast or exploring an interactive map of endangered languages.

- ‹ previous

- 89 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators