Features

This is the latest in the Artistic Licence series.

Growing up in Germany, studying in English, speaking Russian with her parents, and learning French in Belgium: languages have always been a central part of Swetlana Schuster’s life.

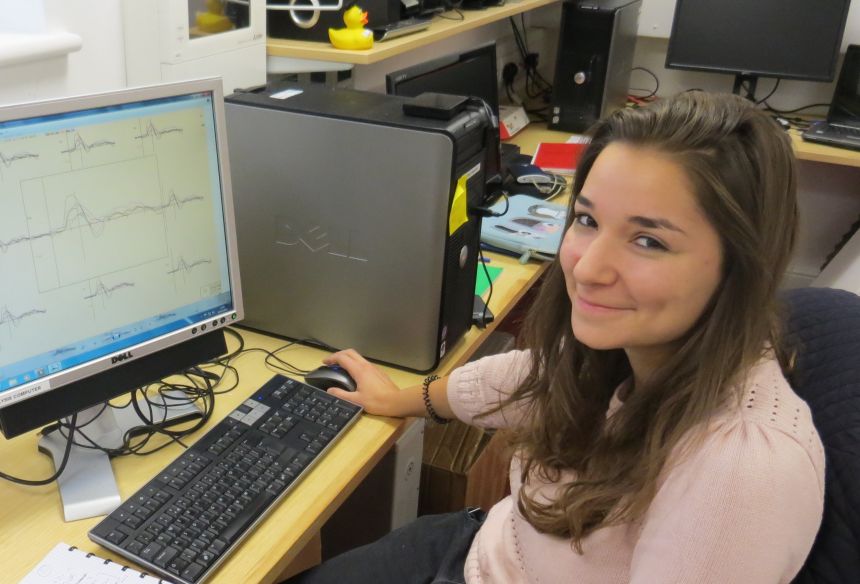

And now she’s a PhD student at Oxford’s Language and Brain Lab, using scientific techniques to see how languages make our brains tick.

“I was always really interested in linguistics, even when I didn’t know much about the academic discipline," she says. "At that point, I was really interested in learning languages.

“And I wasn’t just interested in mastering a new language. I wanted to know what was going on in our brains when we speak one.”

Swetlana is a native German speaker, and grew up in Aachen, Germany. After a childhood learning French and English, and making her own connections between the languages, Swetlana sat down in a lecture theatre at Cambridge for her very first lecture on psycholinguistics.

“I was just blown away. It was incredibly interesting,” she remembers.

Three years later, she came to Oxford to complete an MPhil at the Language and Brain Lab. Now, she’s in the midst of a PhD (or DPhil, as they are known here), working with Professor Aditi Lahiri, and her own experiences have always criss-crossed with her research interests.

Swetlana’s research looks at how native German speakers process words in the brain. This work has also made Swetlana think more about how our brains respond to second (or third or fourth or fifth) languages when we learn them.

Her research has taken her from Leipzig to Chicago to California, using the sort of equipment that we’re more likely to associate with the sciences than the humanities.

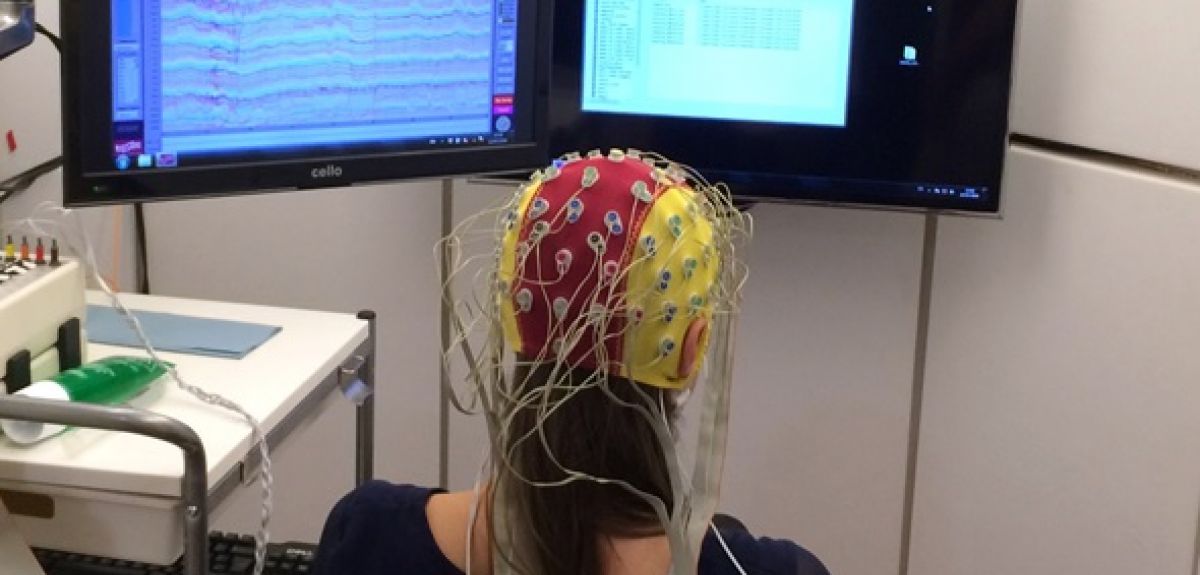

“We use fMRI scanners and an EEG system for part of the experiments,” Swetlana explains.

This means that Swetlana has spent a lot of time examining fMRI scans and carefully placing electrodes onto participants’ heads. She even had the opportunity to run experiments at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig.

“The process of collecting your data can be quite challenging, especially when you’re running experiments abroad,” she says. “But Leipzig was such an exciting opportunity. I learnt so much from collaborating and sharing ideas.”

Now back in Oxford, Swetlana is writing up her research and making the most of Oxford life, both within and outside of the Lab.

“There’s something very special about the Linguistics Faculty,” Swetlana says. “It’s a really supportive environment but also intellectually stimulating.”

And outside of work, college life offers the opportunity to see what else is going on in Oxford’s labs and libraries.

“It’s really fun to be friends with people who have interests in areas completely different to you,” she says.

This is especially interesting for Swetlana, who has thought about how her brain scans and electrodes, which some might think are out of place among the manuscripts and archives of the humanities, fits in to humanities research.

“The idea in our Faculty is to see how everything is connected,” she says. “Looking at how languages change over time, for example. I love how we contribute different approaches to the big questions.”

Another big question is how Swetlana’s research relates to her own language-learning brain.

“It’s made me think about my own languages,” she says. “Bilingualism is something we’re looking into more and more, sometimes from unexpected angles.”

After her DPhil, Swetlana hopes to carry on in research. She’s also interested in language technology, and how language-learning apps could help us learn languages more effectively - so that we, too, could learn to gossip in German or flirt in French.

“I’ve really enjoyed the past six years,” Swetlana says. “And I’m excited to keep on exploring.”

Swetlana is studying a PhD in linguistics

Swetlana is studying a PhD in linguisticsAn artist at Oxford University has won the 2017 Film London Jarman Award.

Oreet Ashery was recently appointed as Associate Professor of Contemporary Art at The Ruskin School of Art and a Fellow of Exeter College.

She has made an immediate impact, winning the prestigious award for UK-based artists working with the moving image. Her successful entry was a 12-part, web-based video series called Revisiting Genesis.

The series looks at the modern death industry and follows an artist with cystic fibrosis and a painter who has had cancer, as well as carers, friends and curators. The films contained stories of Syrian refugees and the people trying to help them, which she recorded in Thessaloniki, Greece earlier this year.

The Guardian interviewed Oreet about her work here.

'I was interested in how people work together,' Oreet told The Guardian. 'Telling stories in a darkened room. Even if no one speaks, that is a story, too.'

Anthony Gardner, Head of the Ruskin School of Art , said: 'We're thrilled that Oreet's enormous talent has been recognised with this award, given in honour of one of the UK's great film-makers to celebrate the next generation of artists using film and moving-image.

'And like Derek Jarman himself, Oreet is not only a great artist but also a great teacher and mentor, which makes her success with the Jarman Award even more fitting.'

The Ruskin School of Art has punched above its weight in the art prize categories in recent years. In the last three years alone, its tutors and alumni have won two Turner prizes (Elizabeth Price and Helen Marten), one Hepworth prize (Helen Marten) and now a Jarman Award.

The Film London Jarman Award recognises and supports the most innovative UK-based artists working with moving image, and celebrates the spirit of experimentation, imagination and innovation in the work of emerging artist filmmakers.

Launched in 2008 and inspired by visionary filmmaker Derek Jarman, the Jarman Award is unique within the industry in offering both financial assistance and the rare opportunity to produce a new moving image work.

There is an interview with Oreet Ashery in The Guardian here. You can watch Revisiting Genesis here.

Oreet Ashery

Oreet AsheryChristina Holka

Research led by Oxford University highlights the accelerating pressure on measuring, monitoring and managing water locally and globally. A new four-part framework is proposed to value water for sustainable development to guide better policy and practice.

The value of water for people, the environment, industry, agriculture and cultures has been long-recognised, not least because achieving safely-managed drinking water is essential for human life. The scale of the investment for universal and safely-managed drinking water and sanitation is vast, with estimates around $114B USD per year, for capital costs alone.

But there is an increasing need to re-think the value of water for two key reasons:

- Water is not just about sustaining life, it plays a vital role in sustainable development. Water’s value is evident in all of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, from poverty alleviation and ending hunger, where the connection is long recognised - to sustainable cities and peace and justice, where the complex impacts of water are only now being fully appreciated.

- Water security is a growing global concern. The negative impacts of water shortages, flooding and pollution have placed water related risks among the top 5 global threats by the World Economic Forum for several years running. In 2015, Oxford-led research on water security quantified expected losses from water shortages, inadequate water supply and sanitation and flooding at approximately $500B USD annually. Last month the World Bank demonstrated the consequences of water scarcity and shocks: the cost of a drought in cities is four times greater than a flood, and a single drought in rural Africa can ignite a chain of deprivation and poverty across generations.

Recognising these trends, there is an urgent and global opportunity to re-think the value of water, with the UN/World Bank High Level Panel on Water launching a new initiative on Valuing Water earlier this year. The growing consensus is that valuing water goes beyond monetary value or price. In order to better direct future policies and investment we need to see valuing water as a governance challenge.

Published in Science, the study was conducted by an international team (led by Oxford University) and charts a new framework to value water for the Sustainable Development Goals. Putting a monetary value on water and capturing the cultural benefits of water are only one step towards this objective. They suggest that valuing and managing water requires parallel and coordinated action across four priorities: measurement, valuation, trade-offs and capable institutions for allocating and financing water.

Lead author Dustin Garrick, University of Oxford, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, explains: ‘Our paper responds to a global call to action: the cascading negative impacts of scarcity, shocks and inadequate water services underscore the need to value water better. There may not be any silver bullets, but there are clear steps to take. We argue that valuing water is fundamentally about navigating trade-offs. The objective of our research is to show why we need to rethink the value of water, and how to go about it, by leveraging technology, science and incentives to punch through stubborn governance barriers. Valuing water requires that we value institutions.’

Co-author Richard Damania, Global Lead Economist, World Bank Water Practice said: ‘We show that water underpins development, and that we must manage it sustainably. Multiple policies will be needed for multiple goals. Current water management policies are outdated and unsuited to addressing the water related challenges of the 21st century. Without policies to allocate finite supplies of water more efficiently, control the burgeoning demand for water and reduce wastage, water stress will intensify where water is already scarce and spread to regions of the world - with impacts on economic growth and the development of water-stressed nations.’

In conclusion, co-author Erin O’ Donnell, University of Melbourne adds: ‘2017 is a watershed moment for the status of rivers. Four rivers have been granted the rights and powers of legal persons, in a series of groundbreaking legal rulings that resonated across the world. This unprecedented recognition of the cultural and environmental value of rivers in law compels us to re-examine the role of rivers in society and sustainable development, and rethink our paradigms for valuing water.’

In the latest animation from Oxford Sparks, experts from the Oxford Genomics Centre talk us through how they 'read' DNA – the 'instruction book' inside of all our cells.

Oxford Sparks is a great place to explore and discover science research from the University of Oxford. Oxford Sparks aims to share the University's amazing science, support teachers to enrich their science lessons, and support researchers to get their stories out there. Follow Oxford Sparks on Twitter @OxfordSparks and on Facebook @OxSparks.

This is the latest in the Artistic Licence series.

Art is part of all our lives. But if you’ve ever tried putting paintbrush to paper, or slipped on a pair of ballet shoes, you’ll know that it’s not easy to make it.

Because most of us can draw a face, or shuffle awkwardly and call it dancing, but few of us will paint sunflowers as well as Van Gogh or tap dance like Fred Astaire. But why not? What makes good art good?

Dr James Grant, philosophy tutor at Exeter College, is using the tools of philosophy to explore that very question.

Looking at artworks across the spectrum - from performance to sculpture to oil painting - he’s exploring what differentiates the doodles from the Dali.

“I want to see if there is an overarching theory of what features make an artwork good,” he says.

And, taking inspiration from Aristotle, he’s come up with a novel argument.

Dr Grant argues that good art exhibits “excellences”.

“Excellences” are attributes that demonstrate high levels of thought, character, and perception. Two key excellences are imaginativeness and good craftsmanship.

So if your artwork is highly creative, and includes a high level of skill, chances are it’ll be a good one.

This might all sound obvious—but Dr Grant’s theory contributes to big debates in philosophy.

He hopes to show that art is not just instrumentally valuable - valuable because it serves a purpose, like making us feel good - but intrinsically valuable - good in its own right.

“I think this provides a new argument for the intrinsic value of art,” he says.

So what is an example of a good artwork that has these excellences?

“I find Chinese jade sculptures very interesting,” Dr Grant says. “Jade is extremely hard to work with, so there’s incredible skill behind these pieces.

“Another example would be Gaudí’s architecture. Not everybody likes it, but it’s imaginative. The Sagrada Familia cathedral is a pretty dramatic manifestation of imaginative thinking.”

Dr Grant hopes that, by thinking about art in this way, we might start to appreciate beauty, and art, differently.

“Many people talk about art as if it’s valuable only because we get pleasure from it. I’m arguing that, when you appreciate and enjoy a good work of art, it’s also true that you get pleasure from it because it’s valuable,” he says.

So that’s all there is to it. If you hone your skills, and think creatively, you too could make art to rival Rembrandt. Better get practising.

- ‹ previous

- 87 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators