Features

The fast pace of disease outbreaks and the regular emergence of new drug-resistant strains makes the development of vaccines increasingly important. Helen McShane, Professor of Vaccinology at the Nuffield Department of Medicine, explains the role of international research collaborations in the global fight against infectious diseases.

Developing new vaccines to protect against disease is a race against the clock. As scientists and clinicians around the world work to tackle outbreaks, the emergence of new drug-resistant strains makes the need for preventative vaccines all the more important.

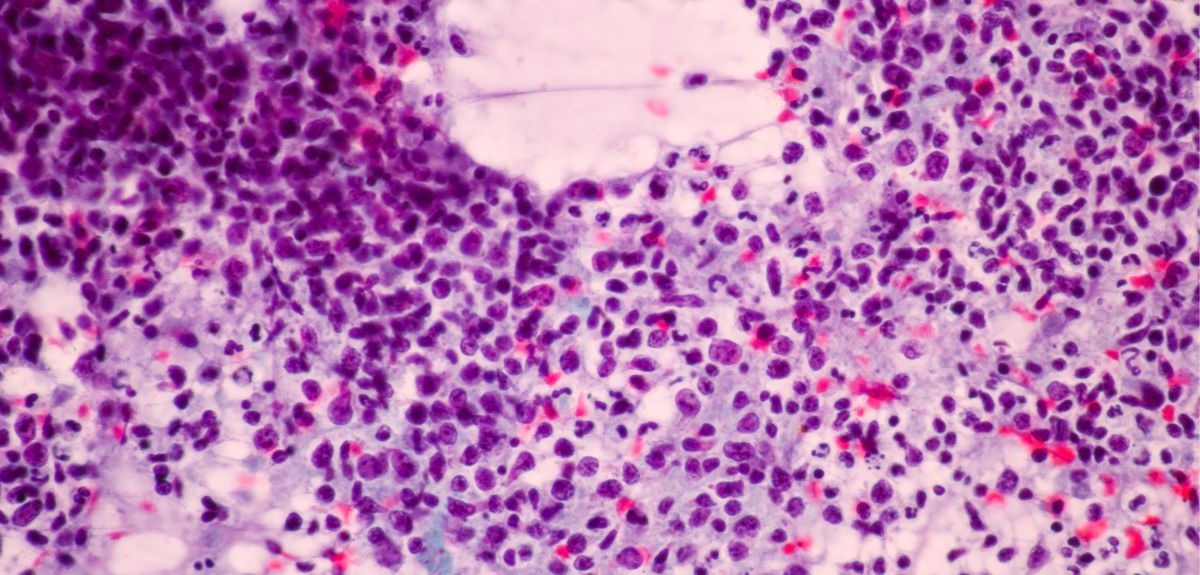

As an example, TB is currently the leading cause of death by infectious disease worldwide, ranking above HIV/AIDS. In 2016, there were an estimated 10.4 million new cases of TB worldwide and 1.6 million deaths. In the same year there were 600,000 new cases with resistance to rifampicin (RRTB), the most effective first-line drug, of which 490 000 had multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). Almost half (47%) of these cases were in India, China and the Russian Federation.

Vaccines are incredibly effective in combatting disease. Current childhood vaccines are estimated to prevent 2-3 million deaths per year worldwide, not to mention the countless lives that have been saved through the eradication of smallpox and the near eradication of polio.

However, the only current vaccine we have against TB is the BCG vaccine, which is almost a century old and only grants limited protection against the disease – especially in high-risk areas.

The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) End TB Strategy, adopted by all WHO member states in 2014, set a target of decreasing TB incidence by 80% and reducing TB deaths by 90% by 2030.

There is a stark gap between where we are and where we need to be, but working together significantly improves our chances of finding new vaccines and treatments. The ace up our sleeve in this ongoing battle is that there are thousands of researchers across the globe tackling the same problems from different angles simultaneously.

Our own team in Oxford, in partnership with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, was recently awarded a £1.7million MRC/BBSRC GCRF grant to set up and lead an international network of researchers working towards vaccine development for TB, leishmaniasis, melioidosis and leprosy – called VALIDATE (vaccine development for complex intracellular neglected pathogens). The VALIDATE Network aims to accelerate this vaccine development as well as to encourage Continuing Professional Development and career progression amongst its members, particularly early career researchers and researchers from LMICs. We currently have 73 members from 37 institutes in 15 countries, but we are looking to grow the network considerably.

Creating an interactive community of researchers who are forming new cross-pathogen, cross-continent, cross-species and cross-discipline collaborations, generating new ideas, taking advantage of synergies and quickly disseminating lessons learned across the network, will help us to make significant progress towards vaccines against the focus pathogens.

This is just one of a number of international collaborations we’re involved with. Through the Medical Research Council’s Vaccine Networks researchers here at Oxford are linked to teams worldwide tackling diseases as broad as malaria, ebola, zika and plague. The UK Government Department of Health together with the MRC and BBSRC launched the UK Vaccine Network as a direct response to the recent ebola and zika outbreaks, which threatened to spread far more widely than they eventually did.

The development and manufacture of vaccines is one of the more complex and slow processes in biopharmaceuticals.

However, multiple vaccine development teams sharing their findings from clinical trials can speed the process up immensely. The UK Vaccine Network has developed a process map to support researchers through the key stages in vaccine development and to help them to identify where bottlenecks could potentially delay progress. Through use of this map, it is hoped that researchers can identify any potential delays well in advance and make plans to overcome them. This should help expedite and streamline vital vaccine development, ultimately enabling more lives to be saved.

Professor Helen McShane is Director of VALIDATE, and Dr Helen Fletcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is Co-Director.

Arts graduates - do you have that one friend who always criticises your degree? Well, we have some good news - a new report released by the British Academy has evidence to back you up.

The Academy has published a report into the skills that the 1.25 million students who study arts, humanities and social science (AHSS) develop through their degrees.

Researchers found that the skills in demand from employers were the same as those developed by studying AHSS: namely, communication and collaboration, research and analysis, and independence and adaptability.

Oxford set the agenda for this kind of research in 2013, when it commissioned a report into the destinations of Oxford graduates of English, History, Philosophy, Classics and Modern Languages.

After tracking the employment history of 11,000 graduates, it found that 16-20% were employed in key economic growth sectors of finance, media, legal services and management by the end of the period. Over the period, the number of graduates employed in these sectors rose substantially.

The British Academy’s report takes this further and pinpoints why it is that AHSS graduates have such success in these fields. And Oxford’s Head of Humanities, Professor Karen O’Brien, is delighted.

"We warmly welcome the report's articulation of the higher level skills and competencies which arts, humanities and social sciences (AHSS) bring to the national workplace,” she says.

“The report demonstrates the valuable ability of AHSS graduates to evaluate ambiguous information and to seek nuanced solutions in contexts of social and cultural complexity.

"At a time when many jobs are likely to be lost through automation, the communicative and analytical skills imparted by AHSS degrees may become more relevant than ever."

An Oxford DPhil candidate has won the student award in the British Ecological Society Photographic Competition for the second year in a row.

Leejiah Dorward, a conservation researcher in the University's Department of Zoology, won the overall student prize for his stunning image of a flap-necked chameleon, taken in Tanzania and titled 'I see you'.

Leejiah also won category awards for three of his other photographs.

'Venomous Vine' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Dynamic Ecosystems category

'Venomous Vine' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Dynamic Ecosystems category 'Home sweet home' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Ecology and Society category

'Home sweet home' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Ecology and Society category 'Shivering sylph' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Individuals and Populations category

'Shivering sylph' - Leejiah's winning picture in the Individuals and Populations category 'I see you' - Leejiah's overall winning picture

'I see you' - Leejiah's overall winning pictureAs David Attenborough's Blue Planet II series on the BBC nears its conclusion, interest in our oceans is perhaps at an all-time high. One of the most memorable episodes focused on the world's coral reefs – in particular, the damage being caused by climate change.

This month, Oxford hosts the European Coral Reef Symposium, which will bring together experts from around the world to exchange ideas and discuss the latest developments in coral reef research, management and conservation. Tickets for the event – well over 500 of them – were booked up within weeks of its announcement.

The conference is organised by Reef Conservation UK (RCUK), along with the University of Oxford and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), with support from the International Society for Reef Studies. This year marks the 20th anniversary of RCUK, which was set up and is still run by early-career researchers with a passion for reef conservation.

Dr Catherine Head from Oxford's Department of Zoology is an RCUK committee member and one of the event’s organisers. She said: 'Coral reefs are on the frontline of climate change impact, suffering from major threats such as last year's climate-induced global coral bleaching, and the physical damage likely to be caused by this year's devastating hurricanes in the Caribbean.

'Meetings such as the European Coral Reef Symposium are crucial in bringing together the best minds in coral reef research and management to share findings and ideas to help tackle the threats to coral reefs while there is still time.'

A coral reef in the Maldives (Kirsty Richards)

A coral reef in the Maldives (Kirsty Richards)The UK has a greater direct stake in coral reefs than might be expected, with more than 60,000 km2 of coral reefs in the British Indian Ocean Territory alone. Globally, Europe hosts 7% of coral reefs within its territories – something that will be explored during the symposium.

And while researchers stress the scale and urgency of the threats to our reefs, they are also keen to emphasise that all is far from lost: popular social media hashtags such as #OceanOptimism highlight conservation success stories in an attempt to inspire new solutions. Meanwhile, the Great British Oceans coalition is campaigning to protect the waters around the UK's overseas territories.

Among the plenary speakers at the Oxford-hosted symposium, being held from 13-15 December, is Professor Madeleine van Oppen from the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the University of Melbourne. Professor van Oppen will be presenting her findings from a large project that is investigating whether species of coral can be cross-fertilised to increase their ability to withstand the effects of climate change, including higher sea temperatures. Looking ahead to the symposium, Professor van Oppen said: 'The focus on coral reef conservation and restoration is timely, as the decline of coral reefs is occurring at an alarming rate. Novel interventions to restore reefs and increase reef resilience are urgently needed.'

Other speakers include Professor Nikolaos Schizas from the University of Puerto Rico, and Professor Pete Edmunds from California State University, who have begun analysing the effects of hurricanes Maria and Irma on coral reefs in the Caribbean. High-profile scientists including Professor Morgan Pratchett from James Cook University in Australia – an expert on the Great Barrier Reef – will present their findings on the devastating, climate-induced bleaching events of the past two years.

Kirsty Richards, an RCUK committee member who is also ZSL's marine and freshwater programme coordinator, added: 'We are excited to have been asked to host the European Coral Reef Symposium in our 20th year – the largest gathering of coral reef researchers in the world in 2017. The interest in the event has been incredible.'

One of the world’s most celebrated mathematicians, Sir Andrew Wiles, is widely known as the man who cracked Fermat’s Last Theorem.

In 1994 Andrew’s proof catapulted him to international fame. He went on to earn some of mathematics’ highest honours, including the Abel Prize and a Copley Medal from the Royal Society. Both his peers and the wider world were gripped by his solving of what was widely believed to be an 'impossible' problem. In 1637 Fermat had stated that there are no whole number solutions to the equation xn + yn = zn when n is greater than 2, unless xyz=0. Fermat went on to claim that he had found a proof for the theorem, but said that the margin of the text he was making notes on was not wide enough to contain it.

At a rare public appearance earlier this week, at the Inaugural Oxford Mathematics London Public Lecture, held in the Science Museum, the audience were treated to revealing insight in to the man behind the maths.

Hosted by mathematician and broadcaster Dr Hannah Fry of University College London, the event featured a lecture followed by an interview including Andrew taking questions from the floor. In front of an audience that included the TV presenter Dara Ó Brian, Andrew addressed a range of questions and shared his thoughts and feelings on everything from his own personal career challenges to the role of maths in society at large.

Answering the question ‘is mathematical skill more nature than nurture?’ he drew a comparison with the film Good Will Hunting, which it is implied that if you are born with a natural aptitude for mathematics, it is easy. ‘There are some things that you are born with that might make it easier, but it is never easy", he said.

‘Mathematicians struggle with mathematics even more than the general public does. We really struggle. It’s hard. But we learn how to adapt to that struggle.’ Of his own struggles, Andrew revealed his belief in the ‘three Bs: Bus, bath and bed.’ Time when you can give into your subconscious and the mind is free to wander away from the immediate problem.

Asked by the comedian Dara Ó Brian, to describe his progress tackling Fermat’s problem, he compared it to three flagpoles in a row, ‘each one higher than the other’ but the ropes that join them ‘sort of sink’ with a ‘particularly big sag in the last one.’

Andrew also talked about his motivations. On the influences that drove his success in proving Fermat’s Last Theorem, and that continue to drive him today, he said: ‘I am always quite encouraged when people say something like: ‘You can’t do it that way.’

When asked his opinion on the skills required to be a great mathematician, he said that he believes that success in the field is more down to character than technical skill. ‘You need a particular kind of personality that will struggle with things, will focus and won’t give up.’ Sometimes the best young mathematicians can’t adapt to this need for struggle, he said. They want to solve things in days. Sometimes it takes much, much longer.

As a specialist in number theory, was he ever tempted to explore other mathematical fields? The answer was an unequivocal ‘no.’ He fell in love with his chosen specialism at a young age and his commitment has never wavered. ‘I confess that I was addicted to number theory from the time I was 10 years old and I have never found anything else in mathematics that appealed quite as much.’

When pressed as to whether his loyalty may be due to feeling less able in other areas, he added ‘definitely true.’

On the subject of exactly what it was that intrigued him most about Fermat’s theorem, he said that he was most captivated by the fact that Fermat wrote down the problem in a copy of a book of Greek Mathematics. ‘It was only found after his death by his son.’

He was so intrigued by the problem that as a student he would ‘sneak off to the library’ to read Fermat. But getting to grips with Fermat did not come easily to him. ‘He had this really irritating habit of writing in Latin.’ To this day Andrew’s Latin remains ‘minimal’.

Pressed on his view on one of the most challenging educational issues, the quality of and attitude towards mathematics at school and in the wider population, he cautioned that the issue is not that children are less interested in maths. ‘Most young people do have a real appetite for mathematics but they are put off by uninspiring teaching.’ When the teachers are not interested in the subjects they teach, it shows and rubs off and ‘gets passed on’ to their students. This is a particular problem at primary level where few of the teachers are mathematicians. As for a potential solution to the ongoing teaching crisis Andrew suggested ‘pay them more.’

Encouraging great mathematicians of the future, he advised them to tackle the ‘impossible problems’ while they were young (teens or undergraduates) and get a taste for research. But, they should buckle-down and ‘be responsible’ when they start their careers.

Andrew also discussed the Millennium Prize Problems, seven mathematical problems that were set by the Clay Mathematics Institute 17 years ago, offering $1 million dollar rewards for each one solved.

One of the problems, the Poincaré conjecture had already been solved in 2003, and of the remaining six, Andrew suggested the Riemann hypothesis is receiving the most attention. First identified by the German mathematician David Hilbert in 1900, the problem ‘says something about the way prime numbers are distributed’ a field where number theorists across the world have been collaborating with huge success over the past two decades.

Andrew shared his view of the beauty of mathematics and what this actually means. He compared solving a mathematical conundrum to walking down a path to explore a garden, designed by the great landscape architect Capability Brown and seeing a new and breathtaking view for the first time. The real thrill is in ‘this surprise element of suddenly seeing everything clarified and beautiful.’

But, like any thing of beauty, you should not stare at a mathematical problem for too long, otherwise ‘the majesty will fade, as is the case with great paintings and music.’ Instead, he prefers to ‘keep walking’ through the garden of mathematics, rediscovering his life’s passion, again and again.

- ‹ previous

- 86 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators