Features

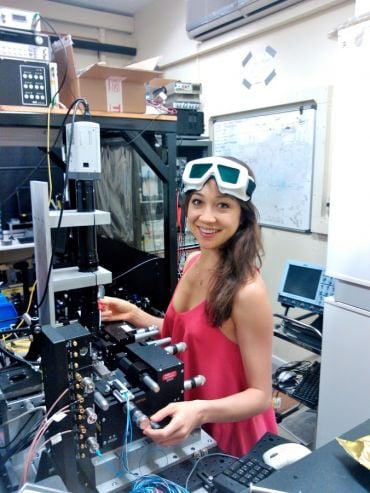

Merritt Moore has achieved what some would call ‘the impossible’: a career as a professional ballet dancer and as an academic quantum physicist. Having quite literally danced her PhD, she is just months’ away from completing her degree in quantum and laser physics. Immediately after graduation she will fly to China to perform at the Beijing National Theatre. Having danced since childhood, she sees great crossover between dance and quantum physics. Earlier this year she combined her passions, collaborating on a meditative science-influenced virtual reality experience called Zero Point Virtual Reality, which is currently running at the Barbican Theatre.

Scienceblog met with Merritt to learn more about fusing her talents and achieving success on her terms.

How did Zero Point Virtual Reality come about?

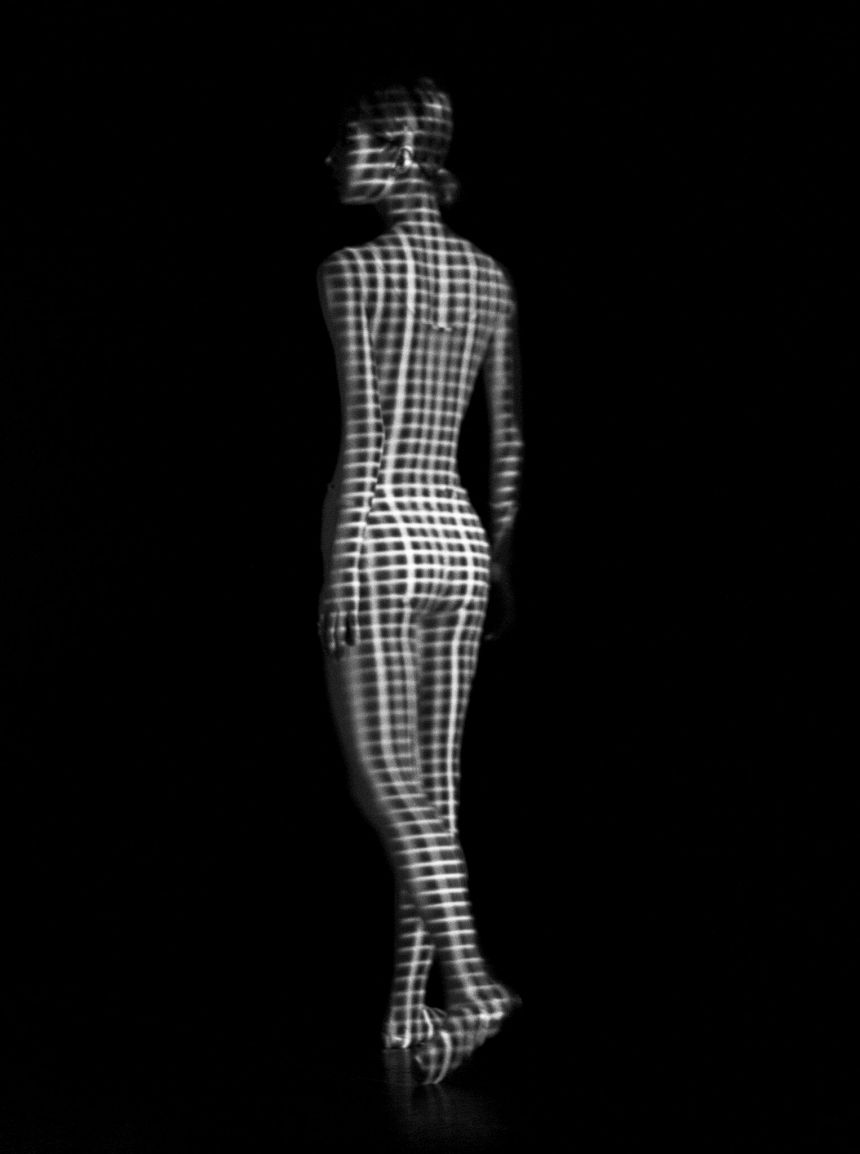

I have danced In a few of [choreographer] Darren Johnston’s productions, including his original Zero Point live performance in 2013. He takes a spiritual approach to his craft, and would often talk about ‘zero-point’ as a state of calm and zen. I introduced him to the concept of zero point energy as a physics phenomenon. A concept that means that there is always energy, even in empty vacuum, where one imagines no energy could exist. When the Barbican invited Darren to bring back his live production Zero Point, it was a natural progression to continue investigating the notion of ‘zero-point’, but this time using technology and dance. This led us to the virtual reality extension of the show.

We put our ideas together and collaborated with the Games and Visual Effects Lab at the University of Hertfordshire, and now we have a meditation experience running in 360° virtual reality (VR), at the Barbican. The end result is sublime and unique, and I hope people like it.

Merritt has juggled her passions of quantum physics and dance since childhood, and sees great crossover between the two.

Merritt has juggled her passions of quantum physics and dance since childhood, and sees great crossover between the two.In what way did you draw on your physics background for the production?

It is an interactive, sensory experience, people walk from scene to scene, taking in the themes. There are quite a few quantum physics-based elements included. For example, in quantum mechanics the systems are constantly evolving, but the minute you try to measure or interfere with them, they stop. We’ve incorporated this by having a moving rock that only moves when you are not looking at it. The approach is very subtle, and a non-scientist probably wouldn’t spot the connection, but it is there. Hopefully it will trigger people to think in a different way.

I’ve always felt that physics and dance have a lot in common. I have a confession that I sometimes read more physics papers when I am preparing for dance meetings than I do for my own research. It inspires me and makes me think about a process, and how I would explain it to someone without all the lingo and technical terminology that we scientists are so used to. Sometimes we ourselves get so lost in jargon, that we forget what things mean, so how can we expect anyone else to understand? The dance community are not scientists, so they ask a lot of ‘why’ questions, which can really throw you. In science, people rarely ask why? They work from facts, so it just is the way it is. It challenges you to think differently and try harder to break things down.

Merritt Moore strikes a pose on the London Underground / Image credit: James Galder

Merritt Moore strikes a pose on the London Underground / Image credit: James Galder

How would you like people to react to it?

The main purpose is to inspire people to view ideas from a different perspective, (literally since with VR you can be placed anywhere). I don’t want to just regurgitate facts, I want to encourage people’s curiosity.

When did you discover your passions for science and dance?

I started dancing when I was 13, which is considered middle-aged in the dance world - most people start as toddlers. Before I discovered dance I was just a girl who loved maths and solving puzzles. I didn’t talk until I was three, so I would communicate through my puzzles. Then I found dance, and was just like ‘this sits in the box of non-verbal activities, I dig this!’ And then, when I found physics, I felt the same way.

You are in your final year at Oxford, what is your thesis investigating?

I am currently working to create large entangled states of light. The more photons - particles of light, you use, the harder it becomes to maintain their quantum properties. Adding more photons makes the whole project more vulnerable to noise, which can destroy their natural state. Understanding how photons behave when you interfere with them can help scientists to explore quantum mechanics phenomena.

Image credit: Merritt Moore

Image credit: Merritt Moore

What drew you to physics?

I love the creativity. Visualising and probing problems that have never been solved before requires a lot of imagination. Often it is mind-bending, and makes no sense. Quantum mechanics is so bizarre - even though the experiment proves again and again that it works, it still makes my head spin.

How do you manage two successful careers in two different fields?

I’ve retired from dance about ten times, burnt my ballet shoes and tried to get so out of shape I would never dance again, but I always come back to it. I honestly never thought I would be a professional dancer. A dance career was a no-go in my family. But I always worked really hard, and achieved the grades I needed. So, when I got to [Harvard] university I was in a position to take a year off to dance with the Zurich Ballet Company. After that I returned for a year, and did the same again the following year, with the Boston Ballet. During the winter break at Oxford I performed with the English National Ballet, and right after leaving here, I will be in Beijing and then on to Edinburgh and Cuba.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s a struggle. I’ve worked a lot. Yes, there have been times that I have felt overwhelmed - when I have been in the lab for over 20 hours a day, sometimes literally sleeping there. But it has always been fun. I’ve realised doing both actually helps me to relax. It’s exercising a different part of the brain and the body and I need it.

What is your ultimate goal?

I haven’t figured out what my title will be yet, but I want to shatter all the stereotypes. The dream is to continue combining physics and dance. I want to dance for the next 10 years, become a principal dancer with a company, and still publish physics papers. I was inspired by the film Interstellar, which, for authenticity, channelled real science into its stunning visuals. Physicists shared insights on black holes and worm holes, and they were converted into special effects for the movie. If I’m able to do something like that, then life is complete.

Quantum physics is one of the more polarising sciences, why do you think that is?

Honestly I think physics in general is really under-sold at school. Classes tend to run the same way, with the standard set of problems that have been done so many times that they are probably online. It’s hard to inspire someone when they know that they can google and memorise the facts. That’s not learning. Technology has evolved so far that most of the information is already there. The asset that we bring to the table, as human beings, is creativity.

I think the way science is taught in schools is very isolating, and self-selecting. There is a misconception that science is technical and geeky, but it is collaborative, imaginative and so much fun.

Do you think that there are any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

I personally have never thought that there is anything that a man can do that a woman can’t. So I had always made a point of avoiding the “women in science” physics societies. I felt that by going, I was making a statement that I saw a difference. But, last year I went to my first meeting and it was amazing, and I thought ‘why didn’t I come sooner?’ I really valued the female camaraderie, and hearing people’s shared experiences. It made me realise that there are serious issues. The ratio of women to men in physics has barely budged in 40 years. You hear a lot of talk about change, but the numbers tell a different story.

Little things make a huge difference, particularly to young girls, and I had no idea. I was having lunch at a young STEM event, for girls aged 11-13. One girl causally looked up at a line-up of the old portraits and said ‘oh there’s a woman - I guess she’s the wife or something’, and the girl next to her said ‘Probably not important.’ My heart sank. I had heard of the Oxford Diversifying Portraiture initiative but never thought anything of it. I would shrug my shoulders and think ‘oh well, it’s history’. But listening to the girls’ highlighted how much, if we really care about getting more girls in science, every little change matters.

Zero Point Virtual Reality is running at the Barbican Theatre until 28 May

A snapshot from the production Zero Point Virtual Reality

Image credit: Darren Johnston

A snapshot from the production Zero Point Virtual Reality

Image credit: Darren Johnston

Legendary Pakistani singer Rahat Fateh Ali Khan has hundreds of millions of views on his YouTube channel.

But he will play to a more intimate audience at Oxford University this week.

He will play alongside Oxford students in a ‘once in a lifetime concert’ at the Sheldonian Theatre tonight.

Rahat Fateh Ali Khan is giving a concert to help raise money to support the work of Oxford University’s Faculty of Music.

The money raised will be invested in further concerts that promote musicians from diverse backgrounds including Indian classical musicians.

He is also donating a harmonium played by his celebrated uncle, Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

Mr Khan is a popular Pakistani singer, primarily of Qawwali, the devotional music of the Muslim Sufis.

‘We are thrilled and honoured to be welcoming distinguished musician Ustad Rahat Fateh Ali Khan,’ says Professor Jonathan Cross of the Faculty of Music. ‘Both as a player of traditional Pakistani Qawwali music and as a leading figure in Pakistani and Bollywood film music, his reputation is global.

‘We expect this to be the first of many concerts of music from the Indian subcontinent hosted by the Faculty. It represents a new and exciting opportunity for our students and staff to engage with these important musical traditions.’

Unfortunately the concert is already sold out. But stay tuned for more Pakistani music coming to Oxford in the future. And in the meantime, enjoy his song Zaroori Tha, which has been watched almost 200 million times:

From drought concerns to political debate and international awareness activity, H₂O has become big news, with good reason. As quickly as the world’s population is rising, international water reserves are diminishing. Despite making up over 70% of the earth’s surface, the bulk of our water reserves are either oceans (97%), or locked up in ice (98% of fresh water supplies), and therefore undrinkable. These changing circumstances have left one in seven people worldwide - that’s over a billion - without access to clean drinking water.

Although near to the sea, countries in the Arabian Peninsula do not have access to rainfall or natural ground water resources and a water crisis is looming. Professor Nick Hankins, Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science talks to Science Blog, about his new research partnership with the University of Bahrain, developing cost-effective water treatment and desalination solutions.

Although near to the sea, countries in the Arabian Peninsula do not have access to rainfall or natural ground water resources and a water crisis is looming. A new Oxford University collaboration will focus on developing solutions to producing water cost-effectively and sustainably in the future.

Image credit: Shutterstock

Although near to the sea, countries in the Arabian Peninsula do not have access to rainfall or natural ground water resources and a water crisis is looming. A new Oxford University collaboration will focus on developing solutions to producing water cost-effectively and sustainably in the future.

Image credit: ShutterstockWhat is sustainable water engineering?

I call my laboratory, the laboratory of sustainable water engineering, I think it explains the work better than chemical engineering. It is a way of thinking about a resource in terms of how we use it, store it, consume it, and recycle it, all of which are incredibly important in water treatment. Future research into sustainability is key to the future of our planet.

It’s often said that water is the new gold. Some dispute it, but the reality is there is a lot of water on this planet, and only a tiny amount of fresh surface water available. My research focuses on developing four key water treatment solutions: the supply of clean, potable drinking water e.g. low energy desalination of seawater, wastewater treatment, water reuse, and finally industrial process water treatment and recycling.

Sustainable water engineering is a way of thinking about a resource in terms of how we use it, store it, consume it, and recycle it. Future research into sustainability is key to the future of our planet.

To have enough fresh water we have to recycle it. It rains, it pours and then we recycle it. Sea water is a largely untapped resource that we need to utilise, but the current costs are just not sustainable.

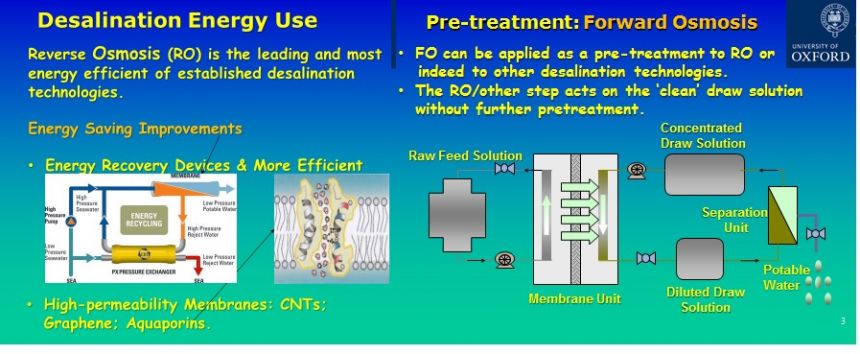

Can you describe desalination?

Desalination is the process of removing all of the salt in seawater. Seawater also contains marine organisms, silt and other materials that reduce the purity of the water. These have to be stripped out to make it drinkable and/or useful to agriculture. It is a lot more expensive than treating rainfall or even wastewater, so any savings that you can make will make a big difference. It is particularly useful in countries that are near to the sea but do not have their own natural water resources, like Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf region in general.

OU

OU

Does your research centre use any specific techniques?

Mining into the world’s seawater resource is key to future water sustainability. Thermal desalination was often used in this area, but the costs are just not sustainable. My research centre specialises in developing cost-effective, lower-energy intensive water treatment techniques.

Reverse osmosis is a popular water purification technology that uses a semipermeable membrane to remove ions, molecules, and larger particles from water under pressure. But I’ve been working on a technique called forward osmosis, which uses less energy. It uses the same principle, only the other way around. A ‘draw’ solution pulls out the water while the salt is trapped by a membrane. The draw agents - magnetic particles or large molecules - are then filtered out from the draw solution or removed by changing the temperature of the water. This allows drinkable water to be extracted, without the need to remove gunk or worry about fouling. It uses less energy and in the long term it could be a good solution to pre-treating the seawater.

The only way forward is to use renewable energy, or to find new ways of reducing the energy costs of treatment processes. Which is exactly the purpose of my research.

How is water treatment useful?

Water treatment has grown in international importance, particularly in the Gulf region. Now that oil resources are running out they are having to diversify economically, and find new ways to save money and conserve energy. As a result there is a lot of government interest in renewable energy, which is energy that is made from natural resources, like solar power, wind turbines and hydropower. Each area has its own challenges, but desalination is one of the most intensive uses for renewable energy.

How did the collaboration with the University of Bahrain (UoB) come about?

The University of Bahrain is in the process of setting up a centre for sustainability, which will focus on renewable energy research.

We recently entered into a four-year partnership with the UoB, which will support the centre to develop sustainable water resources. Our initial research collaboration will investigate ways to reduce the energy consumption associated with the pre-treatment of sea water, which is a necessary but energy-hungry first stage in desalination.

What are the overall project’s aims?

Developing solutions to producing water cost-effectively and sustainably in the future. Work might include irrigating the desert to see if you can grow crops there, or developing ‘seawater greenhouses’ in which desalination is combined with growing crops.

It’s a great opportunity for Oxford that also represents a progressive step forward for Bahrain politically. The country has strong historical links with the UK. They are keen to strengthen international links and work with academic centres of excellence like Oxford.

The clue is in the name, wastewater. We would be crazy not to recycle it. It is already happening in Singapore, where they drink recycled human wastewater. That is where the future is. We are going to have to start looking at our waste differently eventually, so why not now?

What interests you most about the project?

I am thrilled to be involved in an international collaboration where I think there will be a strong and immediate impact. It is also a very exciting opportunity for shared knowledge transfer, supporting a particular and very serious problem. Our findings can be applied straight away in Bahrain and will instantly make a difference to people’s lives.

When will work commence?

We are already up and running. A signing ceremony was held earlier this week at the UoB and attended by a number of state officials including the British Ambassador Simon Martin, the Regional Director of the British Council Alan Rutt and others from local industry.

The project funding includes two research positions, one working with me, in Oxford, and the other will be based at the UoB Sustainability Centre. The next step for us will be recruiting for those positions. We will work in parallel with the team at UoB and will hopefully start field work, conducting seawater analysis in October 2017.

(L-R) Image shows Professor Nick Hankins and University of Bahrain President, Prof. Riyad Hamzah, signing and committing to a four year research partnership. The collaboration will develop avenues to produce water resources cost-effectively and sustainably in the future.

Image credit: UoB

Who will benefit from the research?

The Gulf regions share a common water supply challenge, so those countries will feel the initial benefits. But in the future the work could well be useful internationally and in the UK.

In general though, water desalination has wide benefits and could be useful even in wet countries with rainfall. Even in the UK there can be shortfalls in supply and regional droughts. There is already a desalination plant on the Thames Estuary at Bacton, which supplies clean water to the city of London, so there is scope for collaboration further down the line.

What are your long-term goals with the work?

The initial forecast is for four years, but the potential impact means it could, and hopefully will, run for much longer.

My research centre focuses on water treatment in general, answering questions like ’how do you turn rain water into clean drinking water?’ Another of my key research streams is the biological treatment of wastewater. Recycling wastewater is much more cost and energy-effective than desalination, but it is a concept that scares people. The world is on the brink of a devastating water crisis, so recycling the water used, and using less of it in general is really the only way forward.

The clue is in the name, wastewater. We would be crazy not to recycle it. It is already happening in Singapore, where they drink recycled human wastewater that is now cleaner than tap water. That is where the future is. We are going to have to start looking at our waste differently eventually, so why not now?

Most hip hop promoters could only dream of signing ASAP Rocky and Stormzy.

But last week, they were both in the headlines for stories involving Oxford University.

On Monday, grime artist Stormzy helped one of our students reach her goal of studying for a master’s at Harvard University by donating £9,000 to her crowdfunding page.

Fiona Asiedu, a final-year Experimental Psychology student at New College, says she was “completely overwhelmed” when she saw the donation and that it will be “life-changing” for her.

She met the musician when he visited Oxford’s African and Carribean Society last year, and has promised to thank him by taking him for dinner at Nando’s.

She is now hoping to put any extra money she raises to provide financial support for black British students from low-income backgrounds who gain places at Oxford and Harvard.

The next day, our Twitter mentions blew up after a talk by rapper ASAP Rocky went viral.

Rocky spoke to the Oxford Union back in June 2015 and last week, nearly two years later, a freestyle rap he performed during the lecture was shared online thousands of times.

Part of the reason why both of these stories have been so popular is that people are surprised that these artists would visit Oxford University, which is well-known for its world-leading choirs and classical musicians.

But many people living and studying in Oxford are not surprised – musical tastes and even the University’s music curriculum are changing all the time.

Since 2012, Oxford University has offered a course on global hip hop to first-year undergraduates at Oxford University. To date, nearly 400 students have passed the course.

Earlier this year, the Race and Resistance Programme in The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) hosted a lecture about the cultural value of hip hop.

The lecture hall was full as participants including a professor from Harvard University’s Hiphop Archive and Research Institute discussed the significance of hip hop’s rising popularity.

In his speech, ASAP Rocky said he was pleasantly surprised by what he found in Oxford.

‘‘When I was coming here, I expected to see a bunch of stiff, fancy schmancy people,’ he said.

‘You guys are fancy but you’re not stiff, you’re cool. To come to Oxford and to be walking around and you see people looking like hipsters, you see people who like hip hop, you see people who look kind of regular, who look like they don’t really care about what they wear.

‘It’s really diverse, and it shows the progress, man.’

We cannot confirm the rumour that ASAP Rocky is a devoted reader of Oxford University’s Arts Blog – possibly because we have only just started that rumour.

But in case Rocky is spending his Monday morning browsing this page, we want him to know he is welcome back here any time he wants.

In today’s political climate, science’s value to society is under threat and consistently questioned.

Yet in our everyday lives we reap the rewards of research without even realising it. Take chemistry, for instance. From the flavourings in the food we eat, to the fragrances we wear and the life-saving pharmaceutical drugs that we rely on, the field has a phenomenal impact on the world at large. But this impact often comes with a financial and environmental price attached.

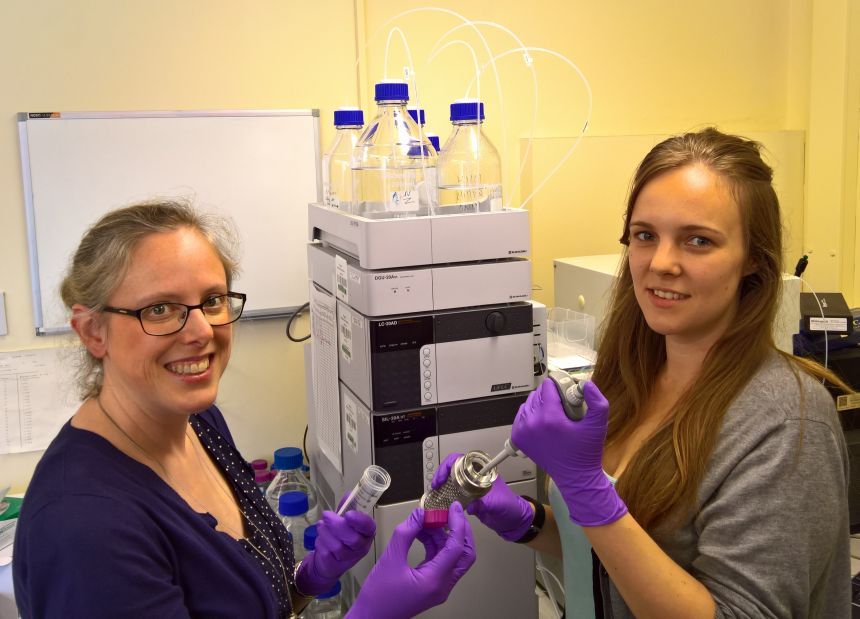

A new Oxford Sparks animation, developed in collaboration with Dr Holly Reeve of Oxford University’s Department of Inorganic Chemistry, breaks down how scientists are working to make the chemicals they produce both cleaner and greener, by highlighting the value of applied science in a real world context. Dr Reeve is co-investigator and manager of HydRegen, an innovative, early-stage, yet already award-winning technology. The product’s name is a play on how it recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Learn more about HydRegen here:

Dr Reeve talks to scienceblog about her role in taking one of the university’s most exciting innovations to market and why academics need to get real about science.

Where did the idea for HydRegen come from?

It was the brainchild of my Professor Kylie Vincent’s and our collaborators Oliver Lenz and Lars Lauterbach’s at the Technical University in Berlin. At the start of my undergraduate Masters project, Kylie challenged me to achieve hydrogen driven co-factor recycling by adding two particular enzymes to a carbon particle, the end result hopefully being a method for cleaner, safer chemical products. We had no idea if it would work, but she is a great mentor, and I believed in her vision. After trying every day for six months, we finally cracked it.

The market for HydRegen could be massive, but for now we are focusing on high value speciality fine chemicals, where selectivity is important to the chemicals’ function, for example, the molecules used in pharmaceuticals, food flavourings and fragrance scents. In the future it could be useful for fuel chemicals, but that is a long way off.

How could HydRegen be used?

HydRegen is a clean way of using enzymes to carry out very specific hydrogenation reactions that are essential steps in the production of many chemicals. The market could be massive, but for now we are focusing on high value speciality fine chemicals, where selectivity is important to the chemicals’ function, for example, the molecules used in pharmaceuticals, food flavourings and fragrance scents. In the future it could be useful for fuel chemicals, but that is a long way off.

How has the project evolved over the last three years?

In 2013 we entered the Royal Society Chemistry Emerging Technology Competition and won a prize package which included mentoring. This helped us to start networking and form a picture of the impact that we could have. We then met with Oxford University Innovation, and quickly began to build a picture of the project’s real world value. I then carried on the research as my DPhil project.

Oxford is such a renowned institution, so the opportunities for development are endless. It is a very entrepreneurial environment that offers great training. Supported by Jesus College and the Maths, Physics and Life Sciences (MPLS) division, I was able to take a business and innovation course which has really helped me develop the skills I need for this industry-facing project.

Professor Kylie Vincent and Dr Holly Reeve co-managers of the award-winning HydRegen, which recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Image credit: OU

Professor Kylie Vincent and Dr Holly Reeve co-managers of the award-winning HydRegen, which recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Image credit: OUA lot is often said about innovation, would you describe the University environment as particularly innovative?

I think it is a word that confuses people. To me, innovation is about having great ideas with real world applications, and then working out the best way of achieving them. Oxford is overflowing with great research, which is a pretty good start for that.

I don’t think that the traits you need to be a scientist - creativity, problem solving, persistence and passion - are exclusively male traits.

The growing number of entrepreneurial opportunities mean we now have more and more commercially aware scientists, who are driven by applied science. I think the next generation of scientists are going to have even more to offer. The entrepreneurial training and funding offered make innovation even more attainable, all we need now is more incubator space.

When do you envision the product being available for commercial use?

We won Innovate UK/EPSRC/BBSRC funding in 2016, for a five year grant worth £2.9 million. The aim is to launch HydRegen as a spinout by the end of the project, within the next four years. However, we are currently mapping out some new, related ideas which could get us to market sooner.

What challenges do you anticipate along the way?

At the moment the process works nicely but on such a tiny scale that it couldn’t be implemented in industry, so the challenge is in the scale-up, For instance, trying to make the enzymes required on a larger scale and to implement them cost effectively. Basically, convincing industry that we can ‘beat’ their existing processes on cost, as well as on our ‘green’ credentials.

We often find our academic curiosity and our commercialisation time-line can be conflicting. However, our academic curiosity is what got us here, and we have already come up with some new ideas since we started this project. Overall, it’s a tricky balance between the two, but both are really important to our success.

What are you working on at the moment?

In collaboration with industry partners, we are testing the product’s industrial attainability. Our team has grown from just Kylie and myself to eight members, and each member is working on a different aspect of this scale-up. Understanding the feasibility of mass producing the enzymes and catalytic beads will help us understand how HydRegen could eventually be useful to industry. Next up though, we have some patents to file. Looking forwards, our focus will be on writing a business plan and generating investment.

What learning curves have you encountered building a start-up company?

I try to live as if HydRegen is already a spinout, and as if every decision I make could cost us money. This makes me think slightly differently (balancing the academic and commercial aims of the research) and means I try to present myself more professionally – you never know when you might meet a potential investor or partner company. I often spend the first few minutes of a meeting working out whether I need my academic or business hat on.

As scientists we get really used to interacting with people like us, but outside of the industry people communicate in different ways. A big lesson for me was going to a course in the business school which was a mixture of scientists and MBA (Master of Business Administration) students. The MBA students were more interested in the business potential of the project, rather than the scientific detail.

I learned to break the message right down, to make it quickly accessible to everyone. Even into snappy one liners that really underplay the science involved – which as an academic is quite unsettling, But at the same time necessary.

How do you think scientists could better engage with the public?

I think most academics know that our individual (highly specific) research projects are not easy for the public to digest, and are working on ways to present their work in a real world context. I’ve just made an animation with Oxford Sparks, about industrial biocatalysis, that explains the principles behind producing cleaner chemicals, by bringing biology and chemistry together. Hopefully, by zooming out and explaining the wider topic, you can then zoom back in on our new technology without it sounding quite so alien.

Dr Reeve married her husband Sean at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum in March 2017

Image credit: Charlie Flounders

Dr Reeve married her husband Sean at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum in March 2017

Image credit: Charlie FloundersAre there any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

I personally do not feel that being a woman has held me back, or positively influenced my career, but equally I do respect that there are not enough women in the industry at high levels.

I don’t think that the traits you need to be a scientist - creativity, problem solving, persistence and passion - are exclusively male traits. I grow up on a farm, and there was never any gender discussion, I just did what everyone else did. I remember needing to carry 50kg bags of seed from one part of the barn to the other. They were so heavy! I carried one with everyone watching, and then I started to split the bags into two, and combined them again at the other end. It never occurred to me to say that they were too heavy, or that I couldn’t do it. I just found my own way of getting it done.

In general it doesn’t just come down to being male or female. I think managers need to try harder to treat people as individuals, and manage them accordingly. Everyone has their own strengths, weaknesses and background history that you might not be aware of. People learn in different ways, think in different ways and need different things from you; to get the best from them, you have to learn to take people as they are. It might be harder for line managers, but I think it is important.

When I came to choose my supervisor for my thesis I wanted a scientist of great calibre, but also someone that I could work with and feel comfortable approaching. Kylie turned out to be a perfect match for me. She has been a fantastic role model in a lot of ways.

What has been the most rewarding part of the project?

Interacting with completely different people and knowing that something that we dreamt-up in the lab, out of pure curiosity, could actually be useful to society. That feeling is indescribable and highly addictive.

Have there been any surprises – positive or negative along the way?

There is a lot more writing involved in science than I imagined, whether it is writing academic papers, blogs or grant applications.

I am slightly dyslexic and I used to always get half marks for my spelling, which was really demoralising. I was told that I wasn’t very creative or good with words, so I came to hate Art and English. Now that I have found a subject that I want to write about, that makes me feel creative, I’ve realised that I wasn’t bad at either, I just wasn’t interested.

Did you always want to be a scientist?

I was always fascinated by how things worked on the farm. My Dad and I would take engines apart and then put them back together. I got really fixated on the fuels in cars. He could always explain the differences between car engines, but not the fuels powering them, and that spurred my interest in Chemistry.

I also had a really inspiring teacher, Mrs Chapman, I don’t think I would have gone on to study Chemistry at Oxford if it hadn’t been for her encouragement. It is really important to have a role model that believes in you.

Dr Reeve plays an active role in Oxford's community outreach work. As someone affected by dyslexia she feels strongly that scientists should learn to communicate with different audiences and present their work in a real world context.

Dr Reeve plays an active role in Oxford's community outreach work. As someone affected by dyslexia she feels strongly that scientists should learn to communicate with different audiences and present their work in a real world context.What are your long-term goals?

Eventually I see myself involved with running a spin-out company, and just seeing how far we can take it.

One piece of advice that you would give to other would be scientists entering the field?

Find something that you enjoy and just do it. There is no way I could put as much energy or passion into my work if I didn’t love it. Don’t be scared to push yourself – with every challenge, you learn something new.

- ‹ previous

- 97 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria