Women in science: Cleaner chemicals for a greener planet

In today’s political climate, science’s value to society is under threat and consistently questioned.

Yet in our everyday lives we reap the rewards of research without even realising it. Take chemistry, for instance. From the flavourings in the food we eat, to the fragrances we wear and the life-saving pharmaceutical drugs that we rely on, the field has a phenomenal impact on the world at large. But this impact often comes with a financial and environmental price attached.

A new Oxford Sparks animation, developed in collaboration with Dr Holly Reeve of Oxford University’s Department of Inorganic Chemistry, breaks down how scientists are working to make the chemicals they produce both cleaner and greener, by highlighting the value of applied science in a real world context. Dr Reeve is co-investigator and manager of HydRegen, an innovative, early-stage, yet already award-winning technology. The product’s name is a play on how it recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Learn more about HydRegen here:

Dr Reeve talks to scienceblog about her role in taking one of the university’s most exciting innovations to market and why academics need to get real about science.

Where did the idea for HydRegen come from?

It was the brainchild of my Professor Kylie Vincent’s and our collaborators Oliver Lenz and Lars Lauterbach’s at the Technical University in Berlin. At the start of my undergraduate Masters project, Kylie challenged me to achieve hydrogen driven co-factor recycling by adding two particular enzymes to a carbon particle, the end result hopefully being a method for cleaner, safer chemical products. We had no idea if it would work, but she is a great mentor, and I believed in her vision. After trying every day for six months, we finally cracked it.

The market for HydRegen could be massive, but for now we are focusing on high value speciality fine chemicals, where selectivity is important to the chemicals’ function, for example, the molecules used in pharmaceuticals, food flavourings and fragrance scents. In the future it could be useful for fuel chemicals, but that is a long way off.

How could HydRegen be used?

HydRegen is a clean way of using enzymes to carry out very specific hydrogenation reactions that are essential steps in the production of many chemicals. The market could be massive, but for now we are focusing on high value speciality fine chemicals, where selectivity is important to the chemicals’ function, for example, the molecules used in pharmaceuticals, food flavourings and fragrance scents. In the future it could be useful for fuel chemicals, but that is a long way off.

How has the project evolved over the last three years?

In 2013 we entered the Royal Society Chemistry Emerging Technology Competition and won a prize package which included mentoring. This helped us to start networking and form a picture of the impact that we could have. We then met with Oxford University Innovation, and quickly began to build a picture of the project’s real world value. I then carried on the research as my DPhil project.

Oxford is such a renowned institution, so the opportunities for development are endless. It is a very entrepreneurial environment that offers great training. Supported by Jesus College and the Maths, Physics and Life Sciences (MPLS) division, I was able to take a business and innovation course which has really helped me develop the skills I need for this industry-facing project.

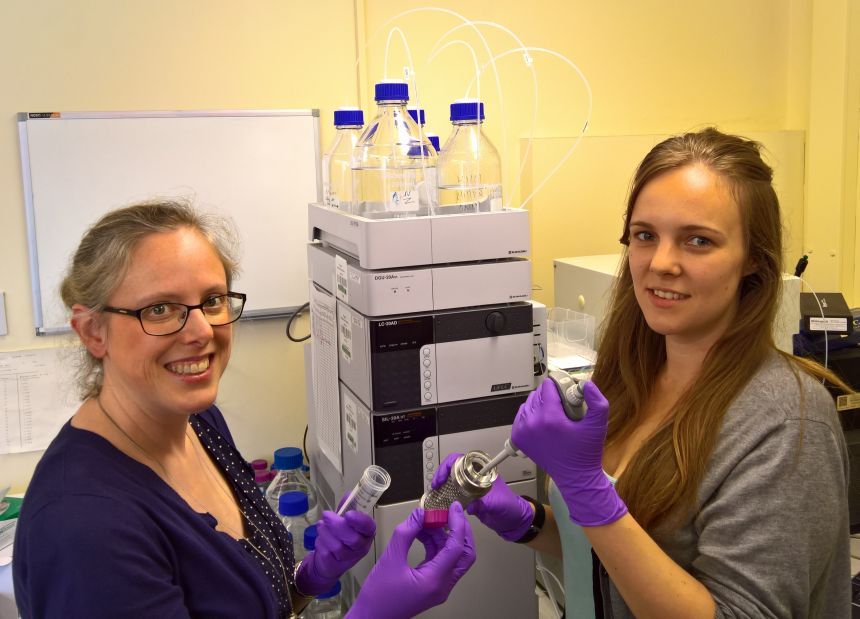

Professor Kylie Vincent and Dr Holly Reeve co-managers of the award-winning HydRegen, which recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Image credit: OU

Professor Kylie Vincent and Dr Holly Reeve co-managers of the award-winning HydRegen, which recycles hydrogen to produce ‘cheaper, faster, safer, cleaner’ chemicals.

Image credit: OUA lot is often said about innovation, would you describe the University environment as particularly innovative?

I think it is a word that confuses people. To me, innovation is about having great ideas with real world applications, and then working out the best way of achieving them. Oxford is overflowing with great research, which is a pretty good start for that.

I don’t think that the traits you need to be a scientist - creativity, problem solving, persistence and passion - are exclusively male traits.

The growing number of entrepreneurial opportunities mean we now have more and more commercially aware scientists, who are driven by applied science. I think the next generation of scientists are going to have even more to offer. The entrepreneurial training and funding offered make innovation even more attainable, all we need now is more incubator space.

When do you envision the product being available for commercial use?

We won Innovate UK/EPSRC/BBSRC funding in 2016, for a five year grant worth £2.9 million. The aim is to launch HydRegen as a spinout by the end of the project, within the next four years. However, we are currently mapping out some new, related ideas which could get us to market sooner.

What challenges do you anticipate along the way?

At the moment the process works nicely but on such a tiny scale that it couldn’t be implemented in industry, so the challenge is in the scale-up, For instance, trying to make the enzymes required on a larger scale and to implement them cost effectively. Basically, convincing industry that we can ‘beat’ their existing processes on cost, as well as on our ‘green’ credentials.

We often find our academic curiosity and our commercialisation time-line can be conflicting. However, our academic curiosity is what got us here, and we have already come up with some new ideas since we started this project. Overall, it’s a tricky balance between the two, but both are really important to our success.

What are you working on at the moment?

In collaboration with industry partners, we are testing the product’s industrial attainability. Our team has grown from just Kylie and myself to eight members, and each member is working on a different aspect of this scale-up. Understanding the feasibility of mass producing the enzymes and catalytic beads will help us understand how HydRegen could eventually be useful to industry. Next up though, we have some patents to file. Looking forwards, our focus will be on writing a business plan and generating investment.

What learning curves have you encountered building a start-up company?

I try to live as if HydRegen is already a spinout, and as if every decision I make could cost us money. This makes me think slightly differently (balancing the academic and commercial aims of the research) and means I try to present myself more professionally – you never know when you might meet a potential investor or partner company. I often spend the first few minutes of a meeting working out whether I need my academic or business hat on.

As scientists we get really used to interacting with people like us, but outside of the industry people communicate in different ways. A big lesson for me was going to a course in the business school which was a mixture of scientists and MBA (Master of Business Administration) students. The MBA students were more interested in the business potential of the project, rather than the scientific detail.

I learned to break the message right down, to make it quickly accessible to everyone. Even into snappy one liners that really underplay the science involved – which as an academic is quite unsettling, But at the same time necessary.

How do you think scientists could better engage with the public?

I think most academics know that our individual (highly specific) research projects are not easy for the public to digest, and are working on ways to present their work in a real world context. I’ve just made an animation with Oxford Sparks, about industrial biocatalysis, that explains the principles behind producing cleaner chemicals, by bringing biology and chemistry together. Hopefully, by zooming out and explaining the wider topic, you can then zoom back in on our new technology without it sounding quite so alien.

Dr Reeve married her husband Sean at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum in March 2017

Image credit: Charlie Flounders

Dr Reeve married her husband Sean at Oxford's Ashmolean Museum in March 2017

Image credit: Charlie FloundersAre there any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

I personally do not feel that being a woman has held me back, or positively influenced my career, but equally I do respect that there are not enough women in the industry at high levels.

I don’t think that the traits you need to be a scientist - creativity, problem solving, persistence and passion - are exclusively male traits. I grow up on a farm, and there was never any gender discussion, I just did what everyone else did. I remember needing to carry 50kg bags of seed from one part of the barn to the other. They were so heavy! I carried one with everyone watching, and then I started to split the bags into two, and combined them again at the other end. It never occurred to me to say that they were too heavy, or that I couldn’t do it. I just found my own way of getting it done.

In general it doesn’t just come down to being male or female. I think managers need to try harder to treat people as individuals, and manage them accordingly. Everyone has their own strengths, weaknesses and background history that you might not be aware of. People learn in different ways, think in different ways and need different things from you; to get the best from them, you have to learn to take people as they are. It might be harder for line managers, but I think it is important.

When I came to choose my supervisor for my thesis I wanted a scientist of great calibre, but also someone that I could work with and feel comfortable approaching. Kylie turned out to be a perfect match for me. She has been a fantastic role model in a lot of ways.

What has been the most rewarding part of the project?

Interacting with completely different people and knowing that something that we dreamt-up in the lab, out of pure curiosity, could actually be useful to society. That feeling is indescribable and highly addictive.

Have there been any surprises – positive or negative along the way?

There is a lot more writing involved in science than I imagined, whether it is writing academic papers, blogs or grant applications.

I am slightly dyslexic and I used to always get half marks for my spelling, which was really demoralising. I was told that I wasn’t very creative or good with words, so I came to hate Art and English. Now that I have found a subject that I want to write about, that makes me feel creative, I’ve realised that I wasn’t bad at either, I just wasn’t interested.

Did you always want to be a scientist?

I was always fascinated by how things worked on the farm. My Dad and I would take engines apart and then put them back together. I got really fixated on the fuels in cars. He could always explain the differences between car engines, but not the fuels powering them, and that spurred my interest in Chemistry.

I also had a really inspiring teacher, Mrs Chapman, I don’t think I would have gone on to study Chemistry at Oxford if it hadn’t been for her encouragement. It is really important to have a role model that believes in you.

Dr Reeve plays an active role in Oxford's community outreach work. As someone affected by dyslexia she feels strongly that scientists should learn to communicate with different audiences and present their work in a real world context.

Dr Reeve plays an active role in Oxford's community outreach work. As someone affected by dyslexia she feels strongly that scientists should learn to communicate with different audiences and present their work in a real world context.What are your long-term goals?

Eventually I see myself involved with running a spin-out company, and just seeing how far we can take it.

One piece of advice that you would give to other would be scientists entering the field?

Find something that you enjoy and just do it. There is no way I could put as much energy or passion into my work if I didn’t love it. Don’t be scared to push yourself – with every challenge, you learn something new.