Features

By Professor Katrin Kohl, Professor of German Literature in Oxford's Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, and Director of the Creative Multilingualism project.

The report on the results of the Language Provision in UK MFL Departments 2018 Survey deserves to be read by everyone interested in the future of our discipline. It is the outcome of a collaboration between the AHRC-funded research programme Language Acts and Worldmaking, the Association of University Language Centres and the University Council of Modern Languages, and this in itself indicates welcome movement towards greater dialogue within the higher education system. The report is important not least because it highlights a conundrum that currently faces Modern Languages departments across the country (those which remain after years of attrition): what should our discipline be called?

The tradition of designating it ‘Modern Languages’ is rooted in the need to distinguish the young upstart from the ‘Classical Languages’ that provided the model for studying languages until well into the 20th century. Meanwhile schools prefer the name ‘Modern Foreign Languages’ – a designation appropriated in the title of this report. Is this what is being suggested as the solution? The focus on ‘foreignness’ buys into an agenda of ‘them’ and ‘us’ that is arguably unhelpful in a climate obsessed with borders designed to keep foreigners out.

Across the secondary and tertiary sectors, it is implicit that ‘ML’ or ‘MFL’ includes the cultures relevant to the languages taught, much as has always been the case with Classics. In universities, this distinguishes ML departments from Language Centres, which tend to focus especially on teaching practical language skills to students across disciplines. The difference in academic purpose often goes hand in hand with differences in perceived status and types of employment contract, and the picture is rendered more multi-faceted still by the fact that some Language Centres provide language teaching for ML departments. In schools, the tradition of teaching literature as part of MFL has weakened, and unlike university departments, which teach much of the cultural ‘content’ through the medium of English, school syllabuses focus on teaching in the target language.

And the complexity doesn’t stop there. Departmental names reflect not only academic traditions but also traditional hegemonies and colonial histories. To take Oxford as an example: the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages teaches only European languages and cultures, but it also embraces those countries in South America and Africa where the lingua franca is Spanish, Portuguese or French. Meanwhile a wide range of Asian languages is taught by the Faculty of Oriental Studies – a name that is justifiable only with reference to tradition and pragmatism. An African Studies Centre was established in 2005, but it does not offer undergraduate courses. And the Language Centre contributes significantly to the more than 50 ancient, medieval and modern languages taught across the University.

In schools, too, ‘Modern (Foreign) Languages’ is traditionally associated only with European languages, although qualifications are available in a wide variety of ‘other’, ‘less-taught’ languages (fortunately, these qualifications were recently rescued from abolition). But the picture is beginning to change as schools become more obviously multilingual, and it is growing palpably illogical to distinguish between ‘Modern Foreign Languages’ as mainstream, and ‘community languages’ or ‘home languages’ as peripheral. Playgrounds are now audibly multilingual spaces where children are speaking languages from right across the world. This is not just the case in large cities – a local Oxford school has pupils speaking over 100 languages. Moreover, Mandarin is now supported by a prestigious government-funded Excellence Programme, and the report highlights that the ‘other’ languages, when combined, now show the highest numbers for A-level ahead of French, Spanish and German. This is not because they are ‘foreign’ languages but because they are rooted right here, in the UK.

So what’s in a name? Ultimately the identity, health and destiny of our discipline.

More than any other academic subject, Modern Languages suffers from a fragmented identity, unhelpful hierarchies and an inability to garner a true spirit of cohesion across sectors and language groups. If the discipline is to survive and make a vibrant contribution to schools, universities and society as a whole, the sectors and languages need to identify not just some common ground but a joint foundation. The discipline needs to address its identity crisis, reinvent itself, and find a unity that is strong enough to embrace diversity without falling apart.

Unpalatable as Brexit may be to many of us, it does provide incentives for promoting the value of all those languages that are spoken both beyond western Europe and within the UK. This need not mean sidelining the teaching of European languages for which we have the teaching expertise, and which underpin many of our closest intercultural relationships. Evidence suggests that fostering competence in one language will bring benefits for learning others, and indeed for one’s native language as well. But to enable our young people to enjoy those benefits, we need to promote language learning as such, and create a context in which every language matters, and can be a means of enriching one’s life, one’s career, and one’s potential to understand others. Languages are relevant to young people not because they are needed for booking a hotel, but because they are all around us, and fundamental to human relationships.

What, then, should be the name of our discipline? The Executive Summary of the report on Language Provision in UK MFL Departments concludes with a tentative preference for ‘Languages’, and eloquently spells out the arguments for that choice:

“In an increasingly multilingual landscape, the survey responses present us with an invitation to reconceptualise our discipline, possibly under a unitary ‘languages’ label, dropping ‘modern’ and ‘foreign’ from its title to strengthen an agenda of inclusion and diversity, integrating all languages, ancient and modern, foreign and local, for those with and without disabilities, as well as a single voice for MFL and IWLP.” (p.7)

Settling on ‘Languages’ as the joint name and common denominator for the reconceptualised discipline would establish the foundation for a strong profile and vigorous public presence. The name would lend itself to embodiment in a website dedicated to promoting the interests of the discipline, providing essential information about ‘Languages’ across sectors, and establishing a hub for initiatives such as ambassador schemes and competitions.

Our model should be STEM – a unified concept coalescing around the promotion of the relevant disciplines in the education system, and formed from extreme diversity. It was invented in the 1990s, became established only in the 2000s and is now so successful that it is sweeping through schools and government policy-making as the only subject area worth studying. There is much that Modern (Foreign) Languages can learn from www.stem.org.uk. The first lesson is to rebrand itself with a simple name. ‘Languages’ even comes with the benefit of stating what’s in the tin.

By Melissa Bedard, MRC Human Immunology Unit, MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine

October is a special time of year. The autumn leaves and crisp air mark the beginning of a new academic term. It also marks the annual announcements of the year’s Nobel Laureates, starting with the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology.

As scientists, we dream that our work today might revolutionise tomorrow – the kind of achievements that are recognised by a Nobel Prize. My research, like that of many immunologists, is primarily basic in nature. This year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology is an exciting reminder that basic immunology discoveries can serve not only as key building blocks to better understanding fundamental immune cell function, but also as therapeutic targets in the fight against immune-mediated diseases.

From the lab bench to the clinic

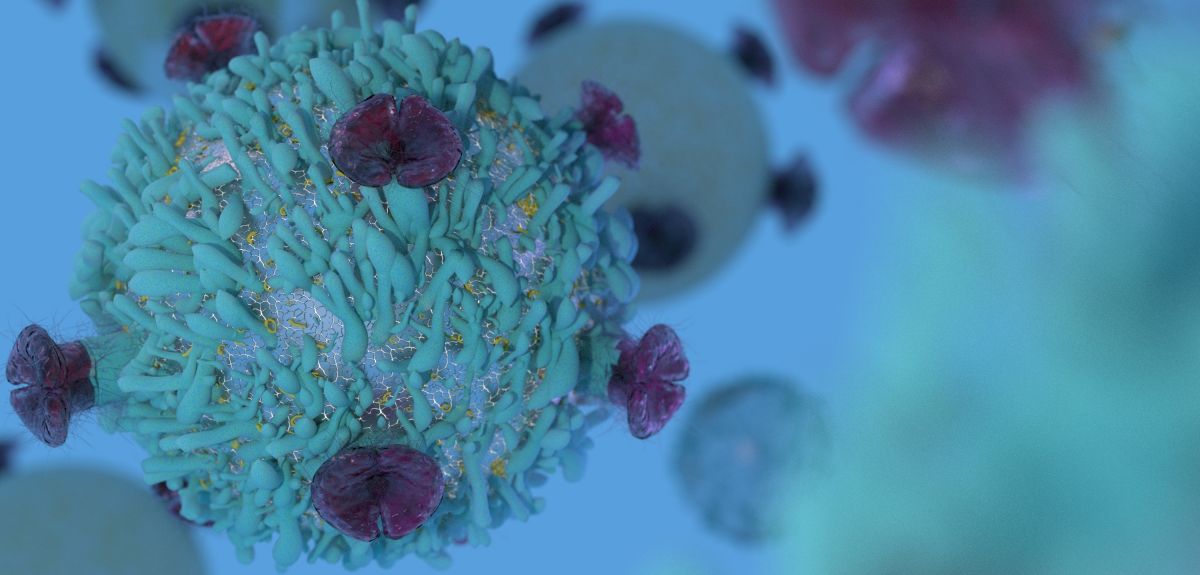

This year’s recipients are Tasuku Honjo and James Allison for their discovery of PD-1 and CTLA-4 respectively. These two important molecules are expressed on the surface of T cells. Stemming from a branch of immune cells called lymphocytes, T cells have the ability recognise and kill unhealthy cells, such as virally infected cells, with a high degree of specificity. With a better understanding of how certain molecules, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, control T cell function, scientists have discovered ways of manipulating T cell responses.

These findings laid the foundations for cancer immunotherapy, a revolutionary approach to treat cancer by enabling your own T cells to recognise and kill tumour cells. This strategy has dramatically changed cancer treatment, and has already benefited millions of individuals living with cancer. For example, before the implementation of cancer immunotherapy around 2010, the three-year survival rate for metastatic melanoma patients was just 10%. As of 2017, it was above 50%. Former American president Jimmy Carter received cancer immunotherapy for advanced melanoma that metastasised to the brain and is today cancer-free – just one example illustrating the power of cancer immunotherapy. Not only are patients’ lives extended, but they also have a better quality of life during treatment than with alternative therapies.

Tracing the immunology of cancer

To fully understand why cancer immunotherapy can be so effective, we must go back to fundamental immunology concepts. Immune cells can discriminate between the body’s own cells, termed ‘self’, and foreign pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria, termed ‘non-self’. Based on this discrimination,one’s immune cells will eradicate foreign pathogens while leaving the body’s own cells unharmed. However, the immune cells’ recognition of and response to tumours is a dynamic and complex matter. This is where the Nobel Prize-winning discoveries fit in.

There are several questions to consider when evaluating the immune response to cancer. Firstly, do immune cells infiltrate tumours? Immune cells extensively infiltrate so-called ‘hot’ tumours, whereas ‘cold’ tumours have few to no immune cells within the tumour tissue. Understanding why certain tumours are ‘hot’ while others are ‘cold’ is an intensive area of research, since immunotherapy, including that stemming from Honjo and Allison’s findings, would be most effective for treating ‘hot’ tumours.

Secondly, if present, are immune cells able to kill the tumour tissue? Even in ‘hot’ tumours, immune cells can be dysfunctional and therefore ineffective – an observation termed the ‘Hellstrom paradox’. Since immune cells are heavily influenced by their surroundings, the environment around the tumour might contribute to impaired anti-tumour immune responses. Certain signalling molecules, called cytokines, can shift the type of response mounted by immune cells. These cytokines act as messengers between cells and can be released from multiple cell types (immune and non-immune), including cancer cells themselves. One class of cytokines called interferons often promote tumour killing, while another cytokine, TGF-b, suppresses tumour killing. The relative abundance of such cytokines in the tumour surroundings can tip the balance between a pro- or anti-tumour immune response.

Binding of specific receptors to PD-1 and CTLA-4 on the surface of T cells (the molecules discovered by the newest Nobel Laureates) inhibits T cell function. Under normal circumstances, PD-1 and CTLA-4 help turn off T cell responses to prevent over-zealous and damaging inflammatory responses (which can contribute to autoimmune diseases like certain types of diabetes). However, in cancer, where T cells must retain prolonged killing abilities, the use of antibodies to block the PD-1 or CTLA-4 interaction with their specific receptors on tumour cells boosts T cell activity so that they remain ‘tumouricidal’. This clinical approach is termed ‘checkpoint therapy,’ the most successful form of cancer immunotherapy to date.

Finally, if infiltrating T cells are effective, can they recognise specific markers on the tumour to kill it? Tumours arise for many reasons, but mutations in the genetic code of individual cells – mutations that cause the cell to multiply unchecked, often contribute to tumour formation. However, these mutations can lead to the production of mutated ‘self’ proteins that no longer resemble normal proteins, and as such immune cells recognise them as ‘non-self’. These mutated proteins are termed ‘neoantigens’ and can be recognised by specific T cells that kill the neoantigen-expressing tumour cells. Identifying and harnessing the power of neoantigen-specific anti-tumour responses is at the forefront of cancer immunotherapy research, especially after Steve Rosenberg’s research group used a cocktail therapy including neoantigen-specific T cells and checkpoint therapy to cure a woman with late stage metastatic breast cancer.

Future directions

Immunologists throughout Oxford, including those at the MRC Human Immunology Unit (MRC HIU) at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine (MRC WIMM), are playing their part in advancing cancer immunotherapy research, particularly in addressing the three questions previously mentioned. Student-led research has centred on a molecule expressed by tumours that binds a receptor on T cells, similar to PD-1, which prevents T cells from infiltrating tumours. This interaction impairs T cells’ physical mobility by altering the cells’ actin cytoskeletons; collaborations between multiple labs in Oxford guided this research component. Other research also ongoing here in Oxford focuses on: (a) the affect of engineered antibodies against another inhibitory molecule, BTLA; (b) analysing tumour-specific T cell populations in melanoma patients over the course of their checkpoint therapy; and (c) fine-tuning the production of PD-1 on T cells to elicit effective anti-tumour responses while limiting a damaging inflammatory response.

Work at the MRC HIU also assesses how the tumour microenvironment contributes to anti-tumour immune responses. We investigate how immune cells are affected by stressful conditions, such as a lack of amino acids or oxygen. Based on these studies, we are assessing the therapeutic potential of manipulating metabolic enzymes differentially expressed in tumours versus immune cells.

Finally, there is ongoing and promising work on neoantigen discovery through understanding the mechanisms of neoantigen expression in ovarian cancer, melanoma, and glioblastoma multiforme, a type of brain cancer.

Final thoughts

All of this exciting immunology research, from basic mechanisms of immune cell function to translation studies, will contribute to a growing pool of knowledge that can guide therapeutic interventions for cancer. This year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine illustrates that basic discoveries in fundamental immunology paired with creative and aspirational thinking can have far-reaching implications for the future of medicine. Scientists at the MRC WIMM, including myself, had the pleasure of hearing Dr Honjo speak about his work last year. As compelling as his research was (and is), it was equally inspiring to see that Nobel Prize winners are fellow, hard-working scientists with the curiosity and appetite to see how far their ideas will go.

When is a picture more than a picture?

That question and many more were thoughtfully considered last weekend at the Re-imagining Cole symposium, held in celebration of Christian Frederick Cole, the first Black African student to graduate from Oxford University. His attendance at Oxford was a racial equality milestone for the University that opened the door for other Black students to follow behind him.

Although his legacy was widely celebrated last year, when a plaque was unveiled at the University in his honour, the image that was circulated as a representation of Cole gave many pause, and triggered a debate about race and representation at Oxford, that continues to this day.

Despite the fact that photography was introduced in 1839, apparently the only image of Cole is a cartoon illustration drawn, in 1878. The illustration verges dangerously close to parody, and some would argue, reinforces the racial stereotypes that Cole’s commemoration had been intended to help counter.

A gowned and open-mouthed Cole is shown on the steps of the Mitre Hotel on Oxford’s High Street, holding a banjo - though thankfully not tap dancing, swaying in a way that implies he could break into a dance at any moment.

Pamela Roberts, Director of Black Oxford Untold Stories, who campaigned for and unveiled Cole’s plaque, said: ‘It made me wonder, why is this the only image of Cole, who produced it and for what purpose?’

She trawled University archives and photographic cartoon catalogues, channelling her curiosity to find a non-caricature image or photograph of Cole into a body of research. This work formed the foundation of the symposium. The public event held at the Bodleian Libraries’ Weston Library, unpacked the background and context of previously unseen caricatures of Cole, and explored why his historic academic achievements were only portrayed as parody. What exactly is so funny about a black man being successful?

The event examined the broader issue of race and representation in art, how Cole’s image contributed to the reinforcement of stereotypes and how these stereotypes stimulate unconscious biases which shape the collective psyche of the University.

The programme brought together academics, historians, students and members of the local community to discuss and debate the ‘reimaging’ of Cole’s image. Some leading academics and artists including: Dr Temi Odumosu (Malmö University), Kenneth Tharp CBE, (Director of the Africa Centre), Dr Robin Darwall-Smith (University College, University of Oxford), Robert Taylor (photographer of ‘Portraits of Achievement’) and Colin Harris (cataloguer of the Shrimpton Caricatures collection at the Bodleian, from which the caricatures of Cole are taken), took part in presentations and round table discussions which brought Cole’s legacy to life.

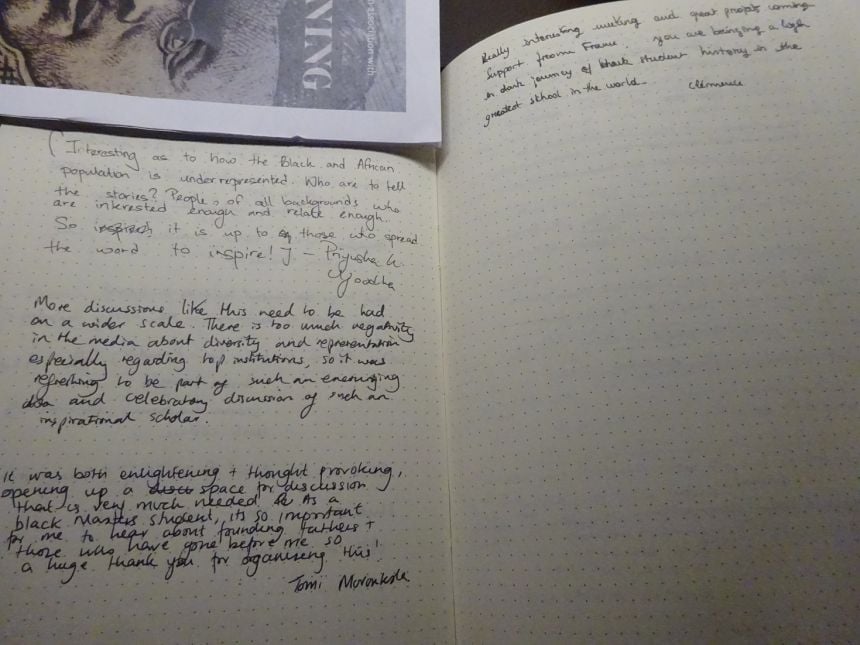

Attendees were then invited to share their personal perceptions of Cole and the impact that his legacy has had on them. During discussions Cole was described as an inspiration, and the event itself as ‘enlightening’ and ‘much needed’.

One student said: ‘As a Black Masters student it is important for me to hear about founding fathers and those who have gone before me, so a huge thank you for organising this!’

Another highlighted a broader need for events of this kind in academia and beyond: ‘More discussions like this need to be had on a wider scale. There is too much negativity in the media about diversity and representation especially regarding top institutions, so it was refreshing to be part of such an encouraging and celebratory discussion about such an inspirational scholar.’

Dr Alexandra Franklin, Coordinator of the Centre for the Study of the Book, at the Bodleian Library, said: ‘The Bodleian Libraries are grateful to Pamela Roberts for convening a symposium full of ideas, debate, and drama. These scholarly exchanges bring archives to life.’

Of the event’s impact, Pamela Roberts said: ‘I am delighted that the symposium reached such a broad, diverse audience. The roundtable discussion concluded that Cole was not only part of Oxford’s story, but Britain’s story and a re-imagined image will afford him the gravitas and greater meaning his achievement and legacy deserve.’

Comments from some of the students who attended the Re-Imagining Cole Symposium

Comments from some of the students who attended the Re-Imagining Cole SymposiumBy Stuart Lee

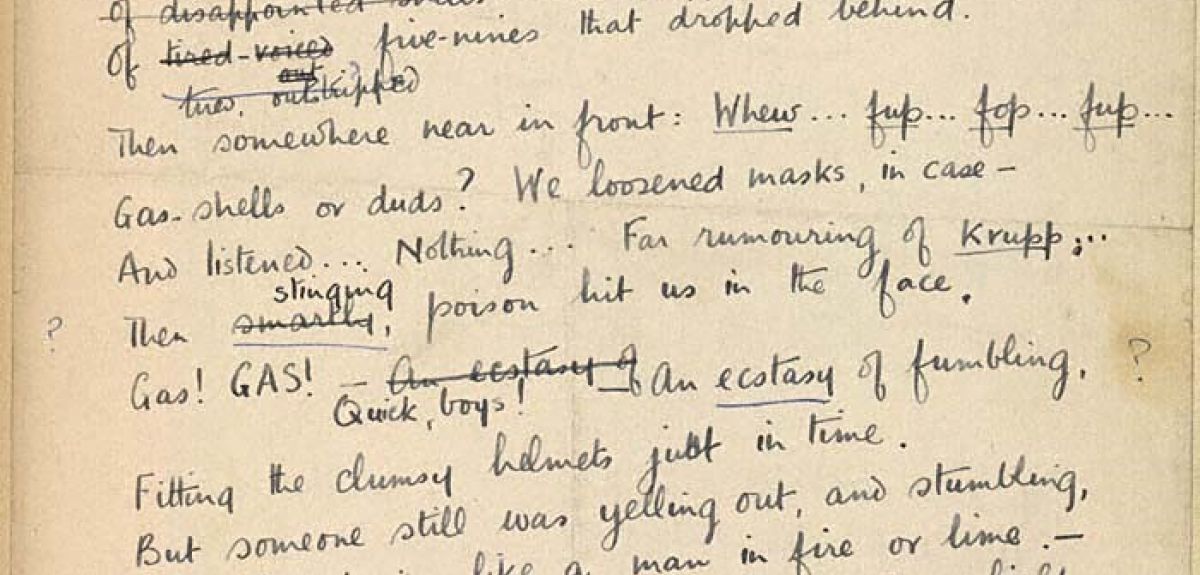

Often heralded as one of the finest poets of the First World War, Wilfred Owen has become a symbol to many of 1914-1918 encapsulating a sense of futility (the title one of his more famous poems), anger, and despair at the suffering endured by the soldiers. This is not without challenge of course. Owen’s was only one voice representing one point of view and cannot be seen to capture the myriad of views and feelings of all the combatants and his generation, but at the same time that is not sufficient reason to dismiss his work as irrelevant to the study of the War.

To commemorate the centenary of the last days of the First World War Poet Wilfred Owen, the University of Oxford’s Faculty of English is posting a daily tweet account of Owen’s last fortnight – @ww1lit using #OwenLastDays – from 22 October to 4 November. Each tweet will detail the activities of Owen and his battalion – 2nd Manchester – as they prepare for the attack. The posts highlight the wealth of free online resources the University has shared online based around Owen and the other war poets under the First World War Poetry Digital Archive and Great Writers Inspire, including podcasts, images of Owen’s manuscripts and letters, film clips, and online exercises.

Wilfred Owen

Wilfred OwenEnglish Faculty Library, University of Oxford / Wilfred Owen Literary Estate

Owen’s battalion was part of the spearhead used to break the final German defensive line after a series of Allied advances following success at Amiens in August. A key problem was to overcome the Sambre canal defences and gain the Eastern bank, and on 4th November at 5.45am Owen was involved in the attempt to cross. The exact details of that morning are hazy, and all that is known is that Owen was seen leading and encouraging his men in the early part of the struggle, but was killed, possibly as he crossed the water on a raft, sometime between 6 and 8.00am. Famously the telegram notifying his family of his death arrived mid-day on November 11th as the celebrations around the Armistice rang out.

The Faculty of English has also launched a nationwide competition for schools to present work (either a poster or recorded performance) on the Legacy of Wilfred Owen (closing date noon, November 30 2018). Prizes include books and vouchers, with the support of Penguin Books who have generously donated editions of Owen’s poems as prizes.

By Elizabeth Frood, Associate Professor of Egyptology in Oxford's Faculty of Oriental Studies

An Egyptologist undertaking fieldwork in Egypt? It doesn’t sound very surprising, does it? Perhaps the subject of that research – ancient graffiti scribbled on temple walls – might be a little more startling. But I am that Egyptologist, and, as I sit in my office in the Sackler library in Oxford a few days after returning, I’m not just surprised, I’m completely stunned. Three years ago I didn’t think it would be possible to return to my work in Oxford, let alone go to Egypt. But I did it, and I still can’t quite believe it.

In August 2015 I went into septic shock due to an infection of unknown origin. The resulting damage to my body was catastrophic: I lost both my legs below the knee, the hearing in my right ear, the internal structure of my nose, and, I reckon worst of all, almost all the function in my hands. My major research project in Egypt, ongoing since 2010, has been to record, analyse and publish graffiti inscribed on the walls of the temple complex at Karnak, on the east bank of the Nile in Luxor. For me, epigraphic recording by drawing had been crucial to understanding the meaning of the graffiti. By drawing I could begin to access an individual’s decision to scribble their name, their image, or a picture of a god, at a particular time and in a particular place. For the longest time I thought my loss of manual dexterity would spell the end of this project.

Thanks to an invitation from Marie Tidball to speak about my fieldwork as part of her TORCH Disability and Curriculum series in October 2017, I began to tentatively explore possibilities for access and recording. It seemed completely abstract to me then – I think I used the word “fantasy” at least two or three times – but it got me thinking and moving forward. I started planning to go.

On September 17 this year I boarded a plane to Luxor, together with my husband Christoph and my three-year-old son Emeran. This first step was really only possible because of very recent radical improvements in my mobility on prosthetic legs and the increased stability and adaptability of what is left in my hands. And, of course, like any fieldwork project, it took a team – my “superteam”, which also included my photographer cousin Jane Wynyard, and two research assistants and coinvestigators, Chiara Salvador and Ellen Jones, postgraduate students in Egyptology at Oxford.

I tried to keep my expectations low (I can hear members of the superteam guffaw as they read this). I wanted to get a sense of the possibilities of Karnak for me as a site. This included testing different methodologies that would enable me to continue working on the graffiti, from ways of collating the drawings I had done before my illness to how we might make future recording possible.

Liz and Chiara collating and discussing the graffiti.

Liz and Chiara collating and discussing the graffiti.Image credit: Jane Wynyard

The first few days were overwhelming. It was incredible to be able to see friends and colleagues whom I hadn’t seen since before I got sick. I cried a lot. I laughed a lot. And I walked a lot, into and around the temple.

I’m lucky that Karnak is a relatively flat site. Wheelchair access has also been made a priority here, thanks to the efforts of the Ministry of Antiquities and dedicated local campaigners. This afforded me smooth, even pathways to one of my project sites – the eighth pylon, a massive gateway in the south of the complex with a graffitied staircase inside. The sandy route to my other project site – a small temple dedicated to the god Ptah bearing many hundreds of graffiti – required a little more concentration and work, but I managed it.

One of the biggest physical challenges for me was, unsurprisingly, the heat. Temperatures could soar to 45 degrees. Prosthetic legs are heavy, hot and clammy under normal circumstances. So getting to my graffiti was a triumph. I had to keep reminding myself of this as I gradually lost perspective over the coming days.

Once I was there, standing in front of the graffiti, anxious about how much work there was left to do, I felt completely and utterly useless. If I couldn’t physically do anything to record, was there any point in me being there? Was I wasting time and money just to make a point? Grief is a sneaky beast – I knew it would hit while I was there, but I didn’t expect it to keep hitting.

Consultation with my team was needed, emotionally and analytically. We talked things through, strategised carefully, and decided to try different ways for me to work. At Ptah, Chiara and I examined our drawings against the originals, and discussed what changes and corrections were needed. I gradually became better at articulating what I saw and how I would have drawn them, so that she could write and draw for me. I struggle so much with feeling dependent. But I began to see this simply as a brilliantly productive extension of the collaborative process that is at the heart of archaeological fieldwork.

I even managed to assist Christoph, my archaeologist husband, to begin digitially mapping the location of the graffiti using an instrument called a “total station”. Incidentally, after 13 years together this was the first time he and I have collaborated in the field!

Ellie undertook photogrammetry to create 3D models and orthophotographs of graffiti whose readings are still problematic, or those which are too high for me to access (I’m not up to climbing ladders just yet). Perhaps all this digital recording is a first step towards creating some virtual reality reconstructions of these graffitied spaces that I, or anyone, can move around in and explore via a computer screen? This was one of my fantasies from the TORCH seminar. It is most certainly an extremely efficient and effective way of creating images that we can now manipulate and work with here in Oxford.

Ellie was also responsible for surveying and checking some of the graffiti at the eighth pylon. As part of this work she took photographs of some highly unusual yellow painted graffiti that I had identified back in 2014. In the course of processing these photographs through a computer program called D-Stretch, Ellie discovered new yellow painted graffiti in the same area. We couldn’t quite believe it, although I should have known better... there is always more graffiti! Such a buzz!

There is no doubt that our work on the graffiti in Karnak has been moved forward significantly by our two weeks there. And I no longer harbour doubts about my role in the field. I need to be there for the continuation and completion of the project. I need to be standing before these walls, climbing these stairs, moving through these gateways, with my team, discussing, observing, feeling…

Some 3,000 years ago very many priests and scribes, even the temple “chef-pâtissier”, sought out shady places or places with good views of processions, festivals or just the temple itself, and decided to leave their names or draw a picture. Often they carved deeply into the stone, and at least one or two thought to use bright yellow paint. Every time I go to Karnak and find their names, I understand a little bit more about what they were trying to do. And I now know that I can continue to go to Karnak to do this. This is both extraordinary and exactly as it should be.

- ‹ previous

- 64 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria