Features

When is a picture more than a picture?

That question and many more were thoughtfully considered last weekend at the Re-imagining Cole symposium, held in celebration of Christian Frederick Cole, the first Black African student to graduate from Oxford University. His attendance at Oxford was a racial equality milestone for the University that opened the door for other Black students to follow behind him.

Although his legacy was widely celebrated last year, when a plaque was unveiled at the University in his honour, the image that was circulated as a representation of Cole gave many pause, and triggered a debate about race and representation at Oxford, that continues to this day.

Despite the fact that photography was introduced in 1839, apparently the only image of Cole is a cartoon illustration drawn, in 1878. The illustration verges dangerously close to parody, and some would argue, reinforces the racial stereotypes that Cole’s commemoration had been intended to help counter.

A gowned and open-mouthed Cole is shown on the steps of the Mitre Hotel on Oxford’s High Street, holding a banjo - though thankfully not tap dancing, swaying in a way that implies he could break into a dance at any moment.

Pamela Roberts, Director of Black Oxford Untold Stories, who campaigned for and unveiled Cole’s plaque, said: ‘It made me wonder, why is this the only image of Cole, who produced it and for what purpose?’

She trawled University archives and photographic cartoon catalogues, channelling her curiosity to find a non-caricature image or photograph of Cole into a body of research. This work formed the foundation of the symposium. The public event held at the Bodleian Libraries’ Weston Library, unpacked the background and context of previously unseen caricatures of Cole, and explored why his historic academic achievements were only portrayed as parody. What exactly is so funny about a black man being successful?

The event examined the broader issue of race and representation in art, how Cole’s image contributed to the reinforcement of stereotypes and how these stereotypes stimulate unconscious biases which shape the collective psyche of the University.

The programme brought together academics, historians, students and members of the local community to discuss and debate the ‘reimaging’ of Cole’s image. Some leading academics and artists including: Dr Temi Odumosu (Malmö University), Kenneth Tharp CBE, (Director of the Africa Centre), Dr Robin Darwall-Smith (University College, University of Oxford), Robert Taylor (photographer of ‘Portraits of Achievement’) and Colin Harris (cataloguer of the Shrimpton Caricatures collection at the Bodleian, from which the caricatures of Cole are taken), took part in presentations and round table discussions which brought Cole’s legacy to life.

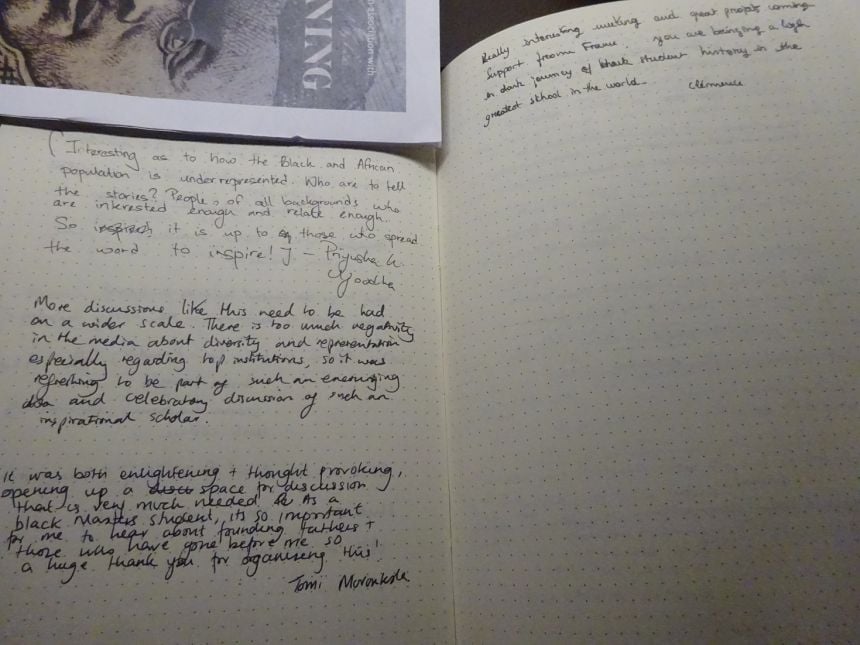

Attendees were then invited to share their personal perceptions of Cole and the impact that his legacy has had on them. During discussions Cole was described as an inspiration, and the event itself as ‘enlightening’ and ‘much needed’.

One student said: ‘As a Black Masters student it is important for me to hear about founding fathers and those who have gone before me, so a huge thank you for organising this!’

Another highlighted a broader need for events of this kind in academia and beyond: ‘More discussions like this need to be had on a wider scale. There is too much negativity in the media about diversity and representation especially regarding top institutions, so it was refreshing to be part of such an encouraging and celebratory discussion about such an inspirational scholar.’

Dr Alexandra Franklin, Coordinator of the Centre for the Study of the Book, at the Bodleian Library, said: ‘The Bodleian Libraries are grateful to Pamela Roberts for convening a symposium full of ideas, debate, and drama. These scholarly exchanges bring archives to life.’

Of the event’s impact, Pamela Roberts said: ‘I am delighted that the symposium reached such a broad, diverse audience. The roundtable discussion concluded that Cole was not only part of Oxford’s story, but Britain’s story and a re-imagined image will afford him the gravitas and greater meaning his achievement and legacy deserve.’

Comments from some of the students who attended the Re-Imagining Cole Symposium

Comments from some of the students who attended the Re-Imagining Cole SymposiumBy Stuart Lee

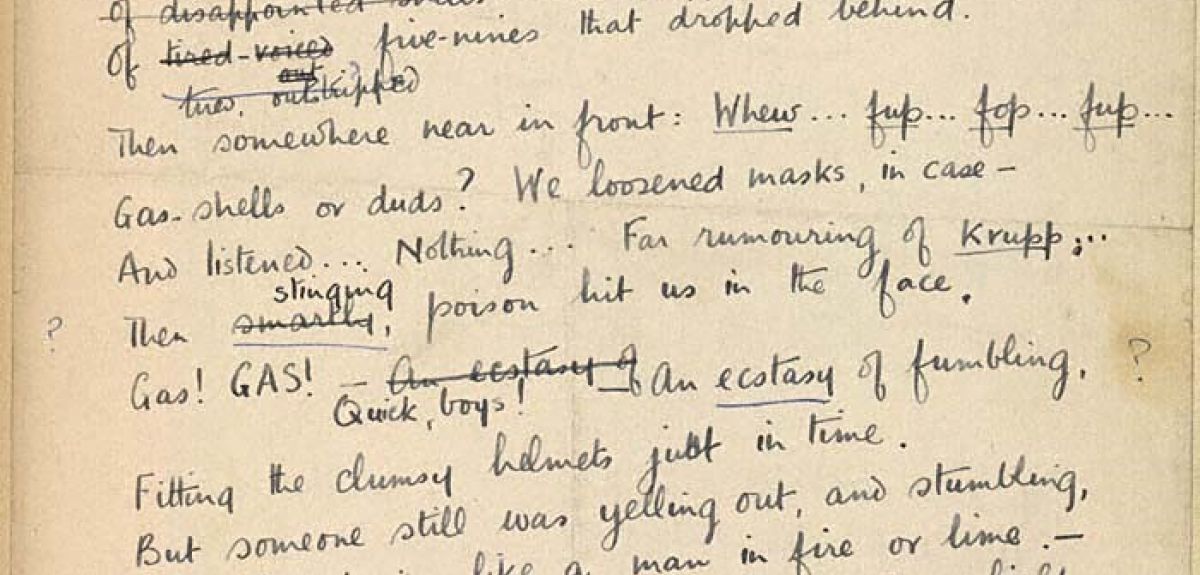

Often heralded as one of the finest poets of the First World War, Wilfred Owen has become a symbol to many of 1914-1918 encapsulating a sense of futility (the title one of his more famous poems), anger, and despair at the suffering endured by the soldiers. This is not without challenge of course. Owen’s was only one voice representing one point of view and cannot be seen to capture the myriad of views and feelings of all the combatants and his generation, but at the same time that is not sufficient reason to dismiss his work as irrelevant to the study of the War.

To commemorate the centenary of the last days of the First World War Poet Wilfred Owen, the University of Oxford’s Faculty of English is posting a daily tweet account of Owen’s last fortnight – @ww1lit using #OwenLastDays – from 22 October to 4 November. Each tweet will detail the activities of Owen and his battalion – 2nd Manchester – as they prepare for the attack. The posts highlight the wealth of free online resources the University has shared online based around Owen and the other war poets under the First World War Poetry Digital Archive and Great Writers Inspire, including podcasts, images of Owen’s manuscripts and letters, film clips, and online exercises.

Wilfred Owen

Wilfred OwenEnglish Faculty Library, University of Oxford / Wilfred Owen Literary Estate

Owen’s battalion was part of the spearhead used to break the final German defensive line after a series of Allied advances following success at Amiens in August. A key problem was to overcome the Sambre canal defences and gain the Eastern bank, and on 4th November at 5.45am Owen was involved in the attempt to cross. The exact details of that morning are hazy, and all that is known is that Owen was seen leading and encouraging his men in the early part of the struggle, but was killed, possibly as he crossed the water on a raft, sometime between 6 and 8.00am. Famously the telegram notifying his family of his death arrived mid-day on November 11th as the celebrations around the Armistice rang out.

The Faculty of English has also launched a nationwide competition for schools to present work (either a poster or recorded performance) on the Legacy of Wilfred Owen (closing date noon, November 30 2018). Prizes include books and vouchers, with the support of Penguin Books who have generously donated editions of Owen’s poems as prizes.

By Elizabeth Frood, Associate Professor of Egyptology in Oxford's Faculty of Oriental Studies

An Egyptologist undertaking fieldwork in Egypt? It doesn’t sound very surprising, does it? Perhaps the subject of that research – ancient graffiti scribbled on temple walls – might be a little more startling. But I am that Egyptologist, and, as I sit in my office in the Sackler library in Oxford a few days after returning, I’m not just surprised, I’m completely stunned. Three years ago I didn’t think it would be possible to return to my work in Oxford, let alone go to Egypt. But I did it, and I still can’t quite believe it.

In August 2015 I went into septic shock due to an infection of unknown origin. The resulting damage to my body was catastrophic: I lost both my legs below the knee, the hearing in my right ear, the internal structure of my nose, and, I reckon worst of all, almost all the function in my hands. My major research project in Egypt, ongoing since 2010, has been to record, analyse and publish graffiti inscribed on the walls of the temple complex at Karnak, on the east bank of the Nile in Luxor. For me, epigraphic recording by drawing had been crucial to understanding the meaning of the graffiti. By drawing I could begin to access an individual’s decision to scribble their name, their image, or a picture of a god, at a particular time and in a particular place. For the longest time I thought my loss of manual dexterity would spell the end of this project.

Thanks to an invitation from Marie Tidball to speak about my fieldwork as part of her TORCH Disability and Curriculum series in October 2017, I began to tentatively explore possibilities for access and recording. It seemed completely abstract to me then – I think I used the word “fantasy” at least two or three times – but it got me thinking and moving forward. I started planning to go.

On September 17 this year I boarded a plane to Luxor, together with my husband Christoph and my three-year-old son Emeran. This first step was really only possible because of very recent radical improvements in my mobility on prosthetic legs and the increased stability and adaptability of what is left in my hands. And, of course, like any fieldwork project, it took a team – my “superteam”, which also included my photographer cousin Jane Wynyard, and two research assistants and coinvestigators, Chiara Salvador and Ellen Jones, postgraduate students in Egyptology at Oxford.

I tried to keep my expectations low (I can hear members of the superteam guffaw as they read this). I wanted to get a sense of the possibilities of Karnak for me as a site. This included testing different methodologies that would enable me to continue working on the graffiti, from ways of collating the drawings I had done before my illness to how we might make future recording possible.

Liz and Chiara collating and discussing the graffiti.

Liz and Chiara collating and discussing the graffiti.Image credit: Jane Wynyard

The first few days were overwhelming. It was incredible to be able to see friends and colleagues whom I hadn’t seen since before I got sick. I cried a lot. I laughed a lot. And I walked a lot, into and around the temple.

I’m lucky that Karnak is a relatively flat site. Wheelchair access has also been made a priority here, thanks to the efforts of the Ministry of Antiquities and dedicated local campaigners. This afforded me smooth, even pathways to one of my project sites – the eighth pylon, a massive gateway in the south of the complex with a graffitied staircase inside. The sandy route to my other project site – a small temple dedicated to the god Ptah bearing many hundreds of graffiti – required a little more concentration and work, but I managed it.

One of the biggest physical challenges for me was, unsurprisingly, the heat. Temperatures could soar to 45 degrees. Prosthetic legs are heavy, hot and clammy under normal circumstances. So getting to my graffiti was a triumph. I had to keep reminding myself of this as I gradually lost perspective over the coming days.

Once I was there, standing in front of the graffiti, anxious about how much work there was left to do, I felt completely and utterly useless. If I couldn’t physically do anything to record, was there any point in me being there? Was I wasting time and money just to make a point? Grief is a sneaky beast – I knew it would hit while I was there, but I didn’t expect it to keep hitting.

Consultation with my team was needed, emotionally and analytically. We talked things through, strategised carefully, and decided to try different ways for me to work. At Ptah, Chiara and I examined our drawings against the originals, and discussed what changes and corrections were needed. I gradually became better at articulating what I saw and how I would have drawn them, so that she could write and draw for me. I struggle so much with feeling dependent. But I began to see this simply as a brilliantly productive extension of the collaborative process that is at the heart of archaeological fieldwork.

I even managed to assist Christoph, my archaeologist husband, to begin digitially mapping the location of the graffiti using an instrument called a “total station”. Incidentally, after 13 years together this was the first time he and I have collaborated in the field!

Ellie undertook photogrammetry to create 3D models and orthophotographs of graffiti whose readings are still problematic, or those which are too high for me to access (I’m not up to climbing ladders just yet). Perhaps all this digital recording is a first step towards creating some virtual reality reconstructions of these graffitied spaces that I, or anyone, can move around in and explore via a computer screen? This was one of my fantasies from the TORCH seminar. It is most certainly an extremely efficient and effective way of creating images that we can now manipulate and work with here in Oxford.

Ellie was also responsible for surveying and checking some of the graffiti at the eighth pylon. As part of this work she took photographs of some highly unusual yellow painted graffiti that I had identified back in 2014. In the course of processing these photographs through a computer program called D-Stretch, Ellie discovered new yellow painted graffiti in the same area. We couldn’t quite believe it, although I should have known better... there is always more graffiti! Such a buzz!

There is no doubt that our work on the graffiti in Karnak has been moved forward significantly by our two weeks there. And I no longer harbour doubts about my role in the field. I need to be there for the continuation and completion of the project. I need to be standing before these walls, climbing these stairs, moving through these gateways, with my team, discussing, observing, feeling…

Some 3,000 years ago very many priests and scribes, even the temple “chef-pâtissier”, sought out shady places or places with good views of processions, festivals or just the temple itself, and decided to leave their names or draw a picture. Often they carved deeply into the stone, and at least one or two thought to use bright yellow paint. Every time I go to Karnak and find their names, I understand a little bit more about what they were trying to do. And I now know that I can continue to go to Karnak to do this. This is both extraordinary and exactly as it should be.

Ahead of a symposium organised by the Oxford Martin School on the Illegal Wildlife Trade, and international IWT conference hosted in London this week, Diogo Veríssimo, from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, reveals how campaigns have attempted to influence harmful consumer habits.

What do elephants, sharks and pangolins have in common? They are all threatened by the illegal trade, be it for their ivory teeth, fins or scales.

Around the world the use of animal and plant parts is increasingly being recognised as a threat not only to wildlife but also to people, as illegal or unregulated movement across vast regions can spread deadly diseases such as Ebola or SARS. While most work to curtail the illegal wildlife trade has focused on law enforcement and surveillance, there are increasing efforts to influence the consumers of these products.

Demand is a key part of any illegal market and while it exists it will be impossible to manage. Conservationists are therefore increasingly working to influence consumers by shifting their buying habits. Together with Anita Wan, currently at Sun Yat-sen University in China, we reviewed the data on this conservation approach, and the results were recently published in Conservation Biology.

Diogo Verissimo

In addition, we found that at continental level, more than a third of campaigns were found in Asia. This is perhaps unsurprising given the significance of key consumer countries such as China or Vietnam. Less anticipated, however, was that the United States held the most campaigns at a national level. This could be explained by the fact that many conservation organisations working on this issue are based there.

One of the key challenges highlighted by this report was that little is known about many of these demand reduction campaigns. For example, we could not pinpoint what year 10% of them took place, and only one quarter of campaigns reported their outcomes.

These gaps in information are not unique for such campaigns, but they now form key priorities for researchers who are coming together next week an Evidence to Action: Research to Address the Illegal Wildlife Trade. This symposium will take place at the Zoological Society of London on October 9, and is co-lead by the Oxford Martin Programme on the Illegal Wildlife Trade (Department of Zoology of the University of Oxford), in collaboration with several other UK Universities and NGOs.

These group of researchers and practitioners have also authored a policy brief that discusses the research gaps surrounding the illegal wildlife trade. This brief will feed into the Illegal Wildlife Trade Conference in London, an international summit organised by the UK Government taking place on the 11 and 12 of October.

Find out more about an Evidence to Action: Research to Address the Illegal Wildlife Trade.

Find out more about the Illegal Wildlife Trade Conference.

Watch the Oxford Sparks video on protecting elephants, protecting humans

Field researchers, Dr Giacomo Zanello, Dr Marco Haenssgen, Ms Nutcha Charoenboon and Mr Jeffrey Lienert explain the importance of continuing to improve survey research techniques when working in rural areas of developing countries.

News about big data and artificial intelligence can leave the impression that a data revolution has made conventional research methods obsolete. Yet, many questions remain unanswerable without working directly with (and understanding) the people whose lives we are interested in. In development studies research, survey research methods therefore remain a staple of data generation, and survey data generation itself remains an active field of debate. In today’s blog, four researchers showcase recent methodological advances in rural health survey research and the advantages they bring to conventional research approaches.

Reaching People at the Margins, 25% off! (Dr Marco J Haenssgen, Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine)

Generating representative data from rural areas of developing countries is a real challenge because often we lack detailed and dependable information on the local population, which makes drawing a sample very difficult. However, recent technological revolutions that we are rather familiar with – the Internet, mobile phone technology, satellite navigation – can also facilitate our work in survey research. Satellite maps in particular help us to:

(1) Select villages more rigorously: We can use satellite maps to generate or verify geo-coded village registers (e.g. censuses or the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) to draw geographically stratified samples. Geo-stratification ensures that we do not accidentally select only “easy” villages that represent less constrained lifestyles in the rural population.

(2) Identify and select houses within the villages more inclusively: Conventional methods to draw a sample of households require either a very laborious enumeration process by going from house to house to establish a sampling frame, and/or are likely to exclude households and settlements at the fringes of a village (e.g. a “random walk”). By using satellite images to enumerate all houses in a village, not only do we save a lot of time and money, but we can also ensure that all parts of a village are represented fairly.

(3) Reach survey sites more efficiently: The logistical benefits cut as much as 25% off the conventional survey costs and time, which can save up to £5,000 for a PhD-level survey (400 respondents in 16 villages) and £40,000 for a medium-sized two-country survey (6,000 respondents in 139 villages).

We need to appreciate that satellite-aided sampling approaches are only an addition to our survey toolkit. They do not work well in urban areas, with mobile populations, or in regions that we are not familiar with. But where they work, they are a real alternative to conventional survey approaches and can make projects feasible that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive, without compromising quality.

Taking Energy Measurement From the Lab to the Field (Dr Giacomo Zanello, School of Agriculture, Policy and Development, University of Reading)

How much energy do you burn during the day (at your job, doing household chores, or at the gym) and is this “energy expenditure” in balance with the calories you take in with your food and drinks? Historically, to answer this question, participants had to spend time in a sealed chamber in a lab which measures the change in oxygen levels while performing activities. While this provides an accurate estimate of energy use, this method is quite impractical to understand real-life settings, particularly for remote areas in a developing country context. It is in these contexts where calorie deficits are most pressing, and yet we do not know much about farmers’ energy use, differences across gender and age groups, or variations of energy use across the seasons and during health or climate-borne adversities.

Recent technological advances allow the measurement of energy expenditures of free living populations to a scale and within a budget inconceivable few years ago. Using Fitbit-like accelerometers we can capture people’s movements and use this information to estimate calorie expenditure. By wearing these devices we follow people’s activities throughout the day, weeks, and seasons and use this information to estimate their energy use. This new glimpse into how people spend their energy can improve health research in multiple domains, for example:

• Having a more accurate assessments of the incidence, depth and severity of undernutrition and poverty,

• Estimating energy requirements for specific livelihood activities, or

• Studying the effect of health conditions and illnesses on livelihood activities.

These are just some possibilities, and the data collected through this innovative methodology extends beyond health-focused research. It also enables us to learn more about how labour is distributed within rural households in developing countries, or measure production in the household and the “informal economy” to produce better estimates of the size of rural economies.

Taking energy measurement from the lab to real-life settings is not without complications. We have to make careful decisions about the devices we use (e.g. easy to wear, not requiring user interaction, not attracting too much attention), build a trusting relationship with our research participants, and acknowledge that even accelerometer-generated data only offers a partial view into energy expenditure and daily activities. Yet even this partial view can afford a completely new understanding of people’s rural livelihood.

A Qualitative Research Update for Social Network Surveys (Ms Nutcha Charoenboon, Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit)

Health and treatment hardly take place in isolation – people around us influence our behaviour, give us advice, or lend us a ride to the hospital. Public health information campaigns, too, are subject to people’s relationships because they might be communicated further or even be instrumentalised for political purposes. Perhaps it is no surprise then that there are calls for more social network research on health in developing countries, but such research faces difficult questions, like how do we ask elicit the names of people in these networks, and how we can match these names in place where one person might be addressed in several different ways (e.g. “Old Father,” “Leader,” Yod Phet, and Ja Bor).

How can we overcome such difficulties? One possibility is cognitive interviewing, consisting of a set of interview techniques to test and interpret survey questions. Among others, interviewees are given survey questions and asked to “think out loud” on how they understand and answer the question, to paraphrase the question in their own words, or to explain village life and the local context. Such information gives researchers a better grasp of local social networks, living arrangements, and people’s understanding of social network questions. In our study in rural Thailand and Lao PDR, it enabled us to drop irrelevant questions, add questions to map health social networks more comprehensively, and to identify mechanisms to locate named contacts within the village more effectively.

But beware of surprises when you carry these methods over to developing country contexts because they tend to assume Western communication norms. Our research participants felt uncomfortable when asked to articulate their thought processes or to answer “why” questions. To cope with such complications, the methods themselves need to be adapted to context, for example by being more closed-ended and by adopting more conventional semi-structured interview techniques.

Shining New Light on Health Behaviours (Mr Jeffrey Lienert, Saïd Business School and National Institutes of Health)

When people get sick, they do not just make a one-off treatment decision like “I’ll go to a clinic / a private doctor / a pharmacist” and stick to it for the remainder of their illness until they are cured. Rather, they go through several phases. For example, a person might first wait and see if it the illness would not go away by itself, then later decide to buy some painkillers to cope with it, visit a private doctor when things do not get better, then lose hope in modern medicines and visit a traditional healer. We gain a lot of information about people’s behaviour if we collect such data on treatment “sequences.”

Not only is it rare for studies to record treatment sequences at all, but there are also no agreed tools for their analysis. First ground has been broken with sequence-sensitive analyses to produce more accurate typologies of behaviour, but we can go further and apply network analysis techniques to make maximal use of sequential data. More detailed analyses can differentiate between the individual steps, explore whether sequences of behaviour resemble each other across people, and which kind of social network is most decisive for such a resemblance. The downside of these arguably more complex analyses is the technical skill required to perform them, but once these methods become more established, they will be able to us to give more detailed (and realistic!) behavioural profiles of different settings and social groups with revolutionarily new insights for health policy.

Methodological innovation enables easier, more precise, and new ways of understanding human behaviour. That does not necessarily mean “big data” and algorithms. Innovation also arises from new combinations of conventional methods with other established techniques and new technologies. Combining rural health surveys with satellite imagery and accelerometers, social network surveys with cognitive interviewing, and healthcare access data with social network analysis does not just keep the methodological debates in survey research alive. It also enables new research, new questions, and a new view on human behaviour.

This blog entry derives from the authors’ contributions to the ESRC NRCM Research Methods Festival 2018 Conference in Bath, drawing on research from the projects Antibiotics and Activity Spaces (ESRC grant ref. ES/P00511X/1), Mobile Phones and Rural Healthcare Access in India and China (John Fell OUP Research Fund ref. 122/670 and ESRC studentship ref. SSD/2/2/16), and IMMANA Grants funded with UK aid from the UK government (ref. #2.03).

- ‹ previous

- 64 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?