Features

As part of our Women in Science series, ScienceBlog meets Professor Tamsin Mather, a volcanologist in the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford University. She discusses her professional journey to date, including recent work with the education initiative Votes for Schools, and why science is the best game around.

What is a typical day in the life of a volcanologist like?

Volcanology is incredibly varied, so there is no typical day. Some days I am out in the field, gathering samples from volcanoes and others I’ll be in the lab, giving lectures, or out in the community, encouraging people to take an interest in science.

What has your professional highlight been to date?

There have been lots, but one of the most exciting was finding fixed nitrogen in volcanic plumes in Nicaragua.

All living things need nitrogen to survive. Although Earth’s atmosphere is mainly made up of nitrogen, its atoms are very tightly bonded into molecules, so we can’t use it. To do so, you need something to trigger their separation. For example, when lightning strikes, the heat prompts atmospheric nitrogen to react with oxygen, forming nitrogen oxides or “fixed nitrogen”. We discovered that above lava lakes, volcanic heat can have the same effect.

Volcanology is incredibly varied. Some days I am out in the field, gathering samples from volcanoes and others I’ll be in the lab, giving lectures, or out in the community, encouraging people to take an interest in science.

Why was the discovery so interesting?

The research shows how volcanoes have played a role in the evolution of the planet and the emergence and development of life.

But that particular trip looms large in my memory because we were robbed while getting the data. I remember it vividly, we had waited all day at the crater edge for the plume to settle, but the sun set before we had a chance to take our measurements. We went back to the national park early the next day, before the security guards arrived, and got robbed at gun point. In retrospect we should have known better, but excitement got the better of us. A terrifying experience but thankfully no one got hurt. We didn’t even get great data that day in the end.

How did you come to specialise in volcanology?

By mistake. When applying for my PhD I put ocean chemistry as my first choice, but I was stumped for my second choice, so browsed the list of topics and the atmospheric chemistry of volcanic plumes stood out to me. I got more and more excited as I read about it, and ended up switching it from my second to first choice. I haven’t looked back.

Do you think being a woman in science holds any particular challenges?

The statistics bear it out - we are still in the minority. There are lots more women in more junior levels now and that will filter through eventually. I definitely would have appreciated more visible female scientist role models when I was younger, but I think the perception of science as a male pursuit is eroding.

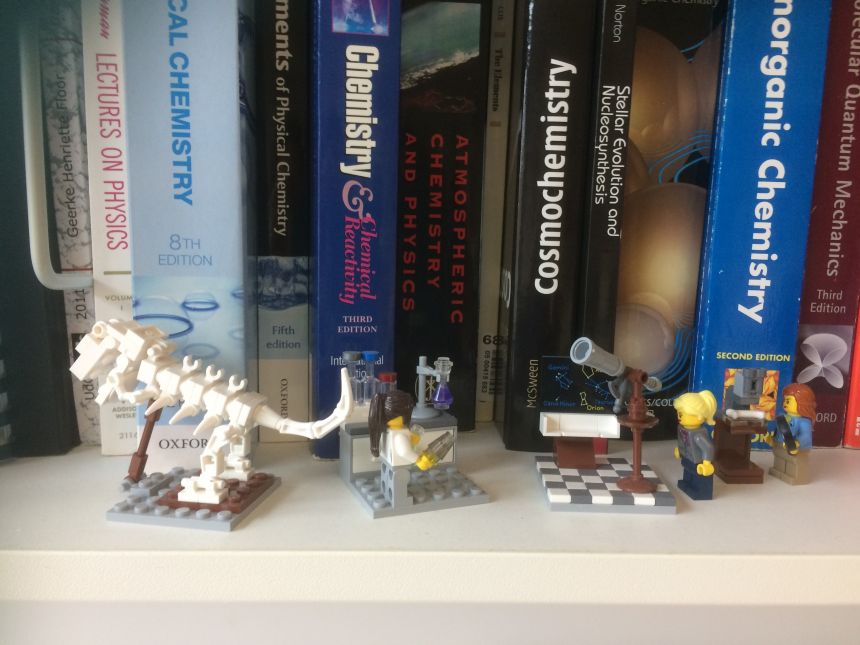

For instance, I used to love Space LEGO, but there wasn’t much diversity in the astronaut characters that came with the kits then. Now, my primary school age daughter loves it too, and the kits are much more diverse. I even have the all-female Research Institute kit in my office. The landscape has changed a lot in the last 20 years, but there is still more to be done.

There isn’t just one solution. Whether in relation to gender or ethnic diversity in science, it is a multi-component problem. If someone is the only woman or ethnic minority in their group, they may feel there is no future role for them. There are so many influencing factors in this situation and they are not all easily articulated or solved.

Science is the best game around. You could be building bridges, curing a disease, developing new apps or climbing a volcano – the world is your oyster. I get paid to discover new things about our planet every day, how cool is that?!

What do you think can be done to encourage more diversity in science?

One of the key challenges for women in academia is the transition from PhD student, to post doc level and on to permanent faculty member. Often at that stage scientists have to relocate frequently. Some of my female contemporaries found this difficult and wanted more stability. Maybe they wanted to be close to a partner, or were thinking about having children. That is not an easy problem to solve and it can be difficult for men too.

There are things that can be done to make this journey easier. Programmes that provide flexible working patterns for outstanding scientists, like the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship scheme, work well, for instance.

The all-female LEGO Research Institute collection, sits in pride of place on Professor Mather's office bookshelf, as a testament to how far gender bias in science has evolved. Copy Right: Tamsin Mather

The all-female LEGO Research Institute collection, sits in pride of place on Professor Mather's office bookshelf, as a testament to how far gender bias in science has evolved. Copy Right: Tamsin MatherWhat are you working on at the moment?

We are studying the volcanoes of the Rift Valley in Ethiopia. Little is known about the history of these volcanoes and how often they erupt. But by measuring the layers of ash that have deposited around them, we can learn more about past and present volcanic activity. It’s possible these volcanoes could be used as energy sources in the future and we are investigating their potential for geothermal development.

How did you get started in science?

I always found it fun and really wanted to be an astronaut, but when I was seven I had an ear operation which killed that dream.

How did you come to be involved in Votes for Schools, the education initiative supporting children to have informed opinions?

It’s a great way to get young people thinking critically about the difference between opinions and facts. We have to empower young people and make sure they realise why having a voice matters. It is important to have an informed opinion, no matter your age. I was asked to join the Votes for Schools team, visiting Packmoor Ormiston Academy to talk about being a female scientist and to launch the primary school version of the scheme.

How did the children respond to your question, ‘Do we need more female scientists and engineers?’

The majority (61%) felt that there were not enough female scientists. The statistics of under-representation, arguments about diverse teams performing better, and the importance of engaging the whole of society in science were key here. Those that responded no, felt women have the right to choose what they want to be, a scientist or otherwise. Cultural background came into play as well, with some saying that women should stay at home.

What were your main takeaways from working with the initiative?

Questions like ‘do you ever work on metamorphic as well as igneous rock?’ really surprised me, and the enthusiasm of staff and children alike was fantastic. They really understood the issues and were not afraid to express their opinions. Technology is so central to our lives now, compared to when I was at school. Smart phones and computer games have become key to how we socialise and have fun. Science and technology are certainly not just for geeks anymore!

What advice would you give to someone considering a career in STEM?

Do it! It’s the best game around. There are so many doors that a career in STEM opens for you. You could be building bridges, curing a disease, developing new computer games or apps or climbing a volcano – the world is your oyster. I get paid to discover new things about our planet every day, how cool is that?!

Although women in science continue to be underrepresented at the highest level, things are slowly changing. In a complex but changing culture, many have built highly successful, rewarding careers, carving out a niche for themselves as a role model to budding scientists, regardless of gender.

In honour of the forthcoming International Women’s Day (March 8th 2017), over the next few weeks, ScienceBlog will be turning the spotlight on some of the diverse and accomplished women of Oxford. Women who, in influencing and changing the world around them with their work, are inspiring a new generation of young people to follow in their footsteps.

Bushra AlAhmadi is a DPhil student in the Department of Computer Science, specialising in cyber security. In 2016 she was awarded the prestigious Google Anita Borg scholarship for women in technology and co-founded the community outreach initiative, InspireHer. The initiative aims to build on young girls’ interest in computer science, by engaging both parent and child with a fun and interactive coding workshop.

How did you come to choose computer science as your field of expertise?

I had a head full of ideas and naturally really enjoyed computer programming; building something from scratch and teaching it to do things. Being able to make something do what you want is both useful and powerful – and that is all coding is. People are just starting to realise that as a skill, it can be useful in lots of areas - not only science areas like engineering, robotics, website development and computing, but also business, law and even retail. It has allowed me to work in multiple fields: programming, security, network security and now cyber security. The freedom of variety to do what you want is really appealing.

What are you currently working on?

My research involves designing malware detection systems, specifically in Software Defined Networks (SDN). Day to day, it involves a lot of coding and testing, trying to find ways to detect and prevent malware. At the moment I am working with external security operation centres' (SOCs) and analysts to understand how they detect malicious activities on the network.

What do you find most challenging about being a woman in science?

As a Saudi Arabian, who completed her master’s degree in California and now lives here in Oxford, I think being a woman in science depends on where you are. Saudi Arabia is actually the place where I feel least aware that I am a 'woman in science'. My university, King Saud University, is divided into single sex campuses, and we actually have an equal number of female and male students studying computer science, if not more. There are around 1,000 female computing undergraduates as well as Master's and PhD students, so we don’t see ourselves as female scientists, just scientists. But, both in the USA and UK, I was always aware of being a minority in my field. Often you are the only woman in your study group.

We need more women and ethnic minorities working in tech, so don’t be afraid to apply just because you are different. In my case it has only been an asset.

In the early stages of my pregnancy, I didn’t want people to think I was less capable of doing my work, so didn’t tell anyone at first and became quite isolated and homesick. But, when I did tell my tutors, the support I got from the university was great, and made me wish I had done so sooner. Everyone from my supervisors to the administrators, went out of their way to make me feel comfortable. Female professors are still a minority at Oxford, but they openly talk about their experiences as women. It’s so important to have relatable role models who talk about motherhood, rather than hiding it away like it is wrong, or that in doing so they are making excuses.

When I attended my first seminar after having my son, I was really nervous. My professor pulled me aside and said: 'if you need to bring your child to a lecture or a meeting, just do it – I have.' It instantly put me at ease and made me realise, it didn’t matter. She was a mum too, like lots of other female scientists. They do not let it hold them back, so I never have either. As a woman and an international student, you feel very welcome and safe here. With everything happening in the world at the moment, I feel very lucky to be here.

What accomplishments are you most proud of to date?

Winning a place on the Google Women Techmakers Scholars Programme, which was formerly known as the Anita Borg Memorial Scholarship Programme (offering financial support to people studying computer science at under graduate or graduate level) was a great honour. On a personal level, doing a PhD while pregnant and having my son in my first year of study is something I am very proud of.

What led you to set up InspireHer?

Female professors are still a minority at Oxford, but they openly talk about their experiences as women. It’s so important to have relatable role models who talk about motherhood, rather than hiding it away like it is wrong, or that in doing so they are making excuse.

As part of my scholarship we were asked to come up with outreach ideas and as a mum, I wanted to engage parents as well, so that they can support and encourage their child’s interest in computer science.

InspireHer is a programme for young girls, who with their parents can become inspired through coding. Through the programme, I often meet parents who think that exposure to technology is bad for their child's development. There are lots of computer and smart tech games that can help children with their maths and science skills development.

Programmes like SCRATCH encourage children to create their own stories, animations and videos.

What can be done to encourage more young girls to choose a career in STEM?

Research suggests that if we want to see more women working in the STEM sciences, we have to engage them at an early age. Having a parent to help and guide them helps feed a child’s interest and boost their confidence. If parents do not understand or value computer science, then their children are not likely to either.

Strong, encouraging role models are really important, especially for younger children (under five) who would not know where to look for coding activities on their own. I am very proud to be a woman in science. There are some great female computer scientists, but to stay that way, we need a new generation to follow suit and a generation after that and after that. Workshops like InspireHer allow young girls to build on their interest in computing, practice activities and then decide for themselves if it is the right career for them.

How can schools better support children interested in science?

Some of the girls attending InspireHer events say they love science, but find school boring. Coding is an interactive and fun way to learn as it is multi-disciplinary and a good skill to develop, whatever field you decide to go into. Teachers could use the robotic ball exercise to make maths and science lessons more hands on. We use it a lot at InspireHer events and the children respond well to it. They learn to code and control the ball, coordinating its movements by using drag, drop and pause options. The game encourages the same step by step approach and problem-solving skills as playing with LEGO or building blocks.

What are your goals for the future?

I am participating in the first Saudi Arabian Cyber Security Contest, which in light of the recent cyber-attacks on Saudi Arabia, is a big deal in my country. Twenty finalists were chosen out of 500 entrants.

When I complete my scholarship in 2018, I will return to Saudi Arabia and teach coding to undergraduates. I am also preparing to launch my own cyber security consultancy business, which I hope will support government and private organisations to develop and build their cyber security capabilities.

What advice would you give to anyone considering a career in computer science?

Believe in yourself and you can make a great impact in any field, especially tech and computing. Don’t be afraid to take the lead, firsts only happen because someone makes them happen. When I started at King Saud University, the only student society was for male law students, (there was nothing for women). I started the first IT Society for Women, organising coding workshops and tech talks. I’ve also been involved with Oxford Women in Computer Science since I arrived at the University in 2014, and was President of the group from 2015 - 2016. We organised the second Oxbridge women in computer science conference, bringing together female researchers from Oxford and Cambridge. Of all the sciences, computing really benefits from and needs diversity. We need more women and ethnic minorities working in tech, so don’t be afraid to apply just because you are different. In my case it has only been an asset.

Two of Oxford's most promising female scientists have been named among five new Fellows of the L'Oréal-UNESCO UK and Ireland For Women in Science programme.

Dr Maria Bruna, of Oxford Mathematics (and a member of the Computational Biology Group in the Department of Computer Science), and Dr Sam Giles, a palaeobiologist in Oxford's Department of Earth Sciences, were selected from 400 applicants for the Fellowships, which were announced at a ceremony hosted by the Royal Society.

The programme aims to support and help increase the number of women working in science and is designed to provide flexible financial help to outstanding female postdoctoral scientists to continue research in their chosen fields. The fellowships, worth £15,000 each, can be spent on whatever the winners may need to continue their research.

Dr Bruna and Dr Giles spoke to Science Blog about their work, their plans for the Fellowships, and the subject of women in science.

Dr Maria Bruna, Oxford Mathematics

'I work on developing mathematical methods to describe systems of interacting particles. These could be used to represent small-scale systems, such as a group of cancer cells in a tumour, or larger-scale systems such as animal flocks. The goal of my research is to understand how collective behaviour emerges from simple interactions between individuals. For example, how do the properties and behaviour of the individual cancer cells determine how the tumour will evolve?

'I can't remember how I first became interested in science, but I've always been a very curious person. I liked all sciences but in particular numbers and building things. That is why I started my studies with an engineering degree, followed by a maths one. Since then, I've found my place in applied mathematics, which allows me to combine my passion for maths with my engineering side.

'I'm very happy and excited to have been awarded this Fellowship. It comes at an ideal time for me, as I'm on maternity leave for the birth of my first son, and I will use the Fellowship to kickstart my research on my return from that.

'Awards like this one are very important to raise awareness of women in science and to help redress the gender imbalance in most sciences. While we have a lot more women in the University now than 50 years ago, I feel that in some sense the culture in academia (with long hours, more administration, scarcity of jobs) is becoming harsher, especially for women and people with young families. Initiatives like the L'Oréal-UNESCO awards, which offer practical support such as paying for childcare costs, are an excellent way to make things a bit easier for us.'

Dr Sam Giles, Department of Earth Sciences

'My research focuses on animals with backbones (vertebrates), a group that today includes over 60,000 species. Vertebrates have an evolutionary history stretching back over half a billion years, so it's really important to look at the fossil record to understand how the group became so hugely successful. Many major innovations, as well as important anatomical features, are found within the braincase, a kind of bony box that sits within the head and houses the brain and sensory organs.

'By using x-ray tomography, it is possible to "virtually" cut through the specimens and produce 3D reconstructions of the brain and braincase anatomy. Comparing these structures between key living and extinct animals allows for major evolutionary events to be put into context.

'I've been interested in science since I was very young, and I used to love reading science books and looking for different kinds of rocks and fossils. When I was at school, my favourite subject was geography – especially physical geography and the study of glaciers and volcanoes. I studied geology at university in Bristol and managed to get a (fairly boring) summer job in the palaeontology lab. As I got more involved in the work (basically picking microscopic fossil fragments out of a very big box), I read around the subject more and got more interested. I also got the chance to work on a beamline at the Swiss Light Source, a large particle accelerator that allows you to use X-rays to look at really tiny structures. This made me want to keep working in the field, and I applied for a DPhil at the University of Oxford. After finishing that, I started a Junior Research Fellowship at Christ Church, Oxford.

'I'm really happy and grateful to have been awarded this Fellowship, especially as it's so flexible, meaning I can use it in multiple ways to help my research: I can pay for my daughter's childcare for the next year, as well as buy expensive computer equipment and travel to international conferences. My plan is to stay in academia and hopefully get a lectureship somewhere.'

Some of the UK's top female scientists will be taking to their soapboxes in Oxford this weekend to share their passion for their subjects with the public.

This Saturday, 18 June, the national Soapbox Science initiative will be making its debut in Oxford. From 2pm to 5pm in Cornmarket Street, 12 female scientists from across the country will be giving a series of fascinating talks on topics as diverse as facial recognition, oral health, the body clock, saving elephants in Mali, and even what tea bags can tell us about soil.

Now in its sixth year, Soapbox Science aims to challenge perceptions of who a scientist is by celebrating the diverse backgrounds of women in science. With speakers ranging from PhD students to professors, Soapbox Science represents the full spectrum of the academic career path and gives the speakers themselves the chance to meet and network with other women in science.

The talks are free and open to the public, and anyone stopping by can expect hands-on props, experiments and specimens, as well as bags of enthusiasm from the speakers.

Carlyn Samuel, ICCS Research Coordinator in the Department of Zoology at Oxford, is coordinating the Oxford leg of Soapbox Science. She said: 'Being part of the great team that has brought Soapbox Science to Oxford for the first time has been an amazing experience. It has opened my eyes to some really interesting research that I would never have heard about otherwise, and I am sure visitors to Cornmarket Street this Saturday will agree.

'Our aim is to bring cutting-edge science to the public in an accessible, fun and unintimidating way. We're hoping to inspire people who never normally get exposed to science – particularly young people. I'm excited that there is such a wide range of topics to learn about, from contentious issues like nuclear energy to saving desert elephants or finding out how chemists have much to learn from nature.'

Among those representing Oxford University on Saturday will be Dr Susan Canney, from the Department of Zoology, whose work involves assessing the threats facing elephants in Mali, and Dr Irina Velsko, from the School of Archaeology, who studies ancient dental calculus and will be talking about how the bacteria that live in our mouths can have a big impact on our overall health.

Soapbox Science co-founder, Dr Nathalie Pettorelli of the Zoological Society of London, said: 'Soapbox Science gives female scientists the much-needed boost to their visibility and profile they need to help achieve equality in science. In the five years of Soapbox, we have seen real impact on the career paths of our speakers, raising their profiles and opening new opportunities for them within the science communities.'

In a guest post for Science Blog, Dr Tessa Baker from the Department of Physics writes about her work on alternative gravity. Dr Baker is one of the new generation of physicists trying to explain 'dark energy', and she recently received a 'Women of the Future' award.

In the late 1990s physicists discovered, to their consternation, that the expansion of the universe is not slowing but accelerating. Nothing in the 'standard model of cosmology' could account for this, and so a new term was invented to describe the unknown force driving the acceleration: dark energy.

We really have no idea what 'dark energy' is, but if it exists it has to account for about 70% of the energy in the whole universe. It's a very big ask to add that kind of extra component to the standard cosmological model. So the other explanation is that we are using the wrong equations – the wrong theories of gravity – to describe the expansion rate of the universe. Perhaps if it was described by different equations, you would not need to add in this huge amount of extra energy.

Alternative gravity is an answer to the dark energy problem. Einstein's theory of general relativity is our best description of gravity so far, and it's been very well tested on small scales; on the Earth and in the solar system we see absolutely no deviation from it. It's really when we move up to the very large distance scales involved in cosmology that we seem to need to modify things. This involves a change in length-scale of about 16 orders of magnitude (ten thousand trillion times bigger). It would be astounding if one theory did cover that whole range of scales, and that's why changing the theory of gravity is not an insane idea.

One of the real challenges in building theories of gravity is that you need to make sure that your theory makes sense at the very large cosmological scales, without predicting ludicrous things for the solar system, such as the moon spiralling into the earth. I don't think enough of that kind of synoptic analysis gets done. Cosmologists tend to focus on the cosmological properties and they don't always check: does my theory even allow stable stars and black holes to exist? Because if it doesn't, then you need to throw it out straight away.

Over the past decade hundreds of researchers have come up with all sorts of ways to change gravity. Part of the problem now is that there are so many different theories that if you were to test each one individually it would take forever. I've done a lot of work on trying to come up with unified descriptions of these theories. If you can map them all onto a single mathematical formalism, all you have to do is test that one thing and you know what it means for all the different theories.

In doing this mapping process we've discovered that a lot of the theories look very different to start with, but at the mathematical level they're moving along the same lines. It suggests to me that people are stuck in one way of thinking at the moment when they build these gravity theories, and that there's still room to do something completely different.

More recently I've moved on to developing ways to actually test the mathematics – to constrain it with data. For example, we can use gravitational lensing. If you have a massive object like a galaxy cluster, the light from objects behind it is bent by the gravity of the cluster. If you change your theory of gravity, you change the amount of bending that occurs. Basically we throw every piece of data we can get our hands on into constraining these frameworks and testing what works.

At this precise moment the data we have is not quite good enough to distinguish between all the different gravity models. So we are doing a lot of forecasting for the next generation of astrophysics experiments to say what kind of capability will be useful in terms of testing theories of gravity. There's still time in some of these new projects to change the design, and I hope to see some of these experiments come on line.

I am very grateful to my former supervisor Pedro Ferreira, who nominated me for the 'Women of the Future' award, and to the Women of the Future scheme. There are two sides to this award; one is the scientific work itself, and the other is the female leadership aspect. In the interview for the award we had quite an extensive discussion about the role of women in science, and what challenges they face. It's a global field-wide issue, and it is changing; it's just going to take time. And in fact Oxford Astrophysics is brilliant for women: Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Katherine Blundell, Joanna Dunkley – they're all really strong female role models.

This blog post first appeared on the Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences Division website.

- ‹ previous

- 3 of 4

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria