Features

For millennia birds have been prized, even hunted, for their beautiful plumage but what makes their feathers so colourful?

A new X-ray analysis of the structure of feathers from 230 bird species, led by Vinod Saranathan of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, has revealed the nanostructures behind certain colours of feather, structures that could inspire new photonic devices.

A report of the research appears in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

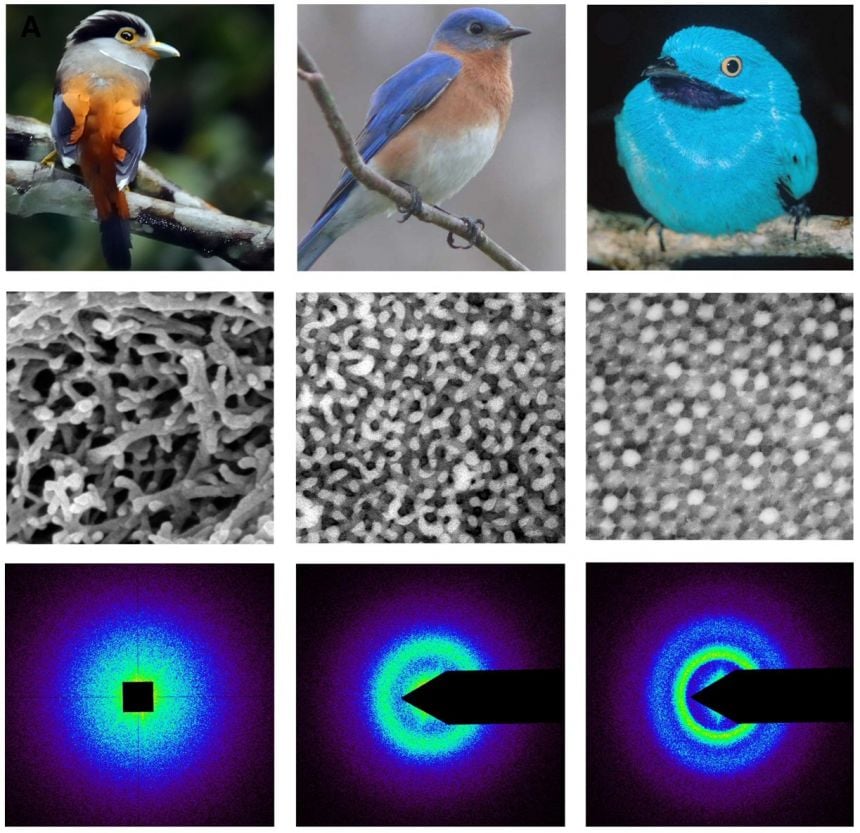

Diversity of non-iridescent or angle-independent feather barb structural colours in birds

Diversity of non-iridescent or angle-independent feather barb structural colours in birds ‘Pigments or dyes are the most common ways to make colour in birds as in other organisms. Pigment molecules absorb certain portions of the white light spectrum and the portions that are not absorbed manifest as the colour we see,’ Vinod tells me.

‘For instance, melanosomes, granules filled with the pigment melanin, produce blacks, browns and reddish-browns in feathers, whereas other pigments such as carotenoids produce the majority of bright yellow, orange or reddish colours.’

He explains that parrots even have their own class of pigments (psittacofulvins) which give them their vivid yellow and red plumage.

‘However, there are no known blue pigments found in vertebrates and the only known green pigment in birds is found in turacos, a group of birds endemic to sub-Saharan Africa,’ Vinod says.

‘Birds have evolved to produce shorter and middle wavelength colours such as violet, indigo, blue and green structurally instead by the scattering of light photons by nanoscale sub-surface features in the feathers that are called biological photonic or biophotonic nanostructures.’

It was these ‘structural’ (as opposed to ‘pigmentary’) colours that Vinod and colleagues from the US set out to investigate.

Vinod explains: ‘These features are basically repeating variation in material composition on the order of a few hundred nanometres, which matches the wavelengths of visible light.

‘In bird feather barbs (barbs and barbules are respectively the primary and secondary branches of a feather), the complex nanostructures, made up of the protein beta-keratin and air, occur in one of two fundamental forms - either as a tortuous network of air channels in keratin (like a porous sponge) or as an array of spherical air bubbles in keratin (like Swiss cheese), but sometimes as more disordered and highly variable versions of these two forms.’

Despite this apparently chaotic arrangement the team’s X-ray scattering experiments found a kind of order (known as ‘quasi-order’) in the variation and sameness of feather structures that accounts for their unusual optical qualities.

Because the quasiordered architecture of barbs interacts strongly with light, often producing double peaks, pure green or red colours cannot be produced structurally. But, Vinod tell me, many birds have evolved a way round this:

‘Some birds such as the tanagers found in the Neotropics, have combined an orange or red pigment with a spongy barb nanostructure tuned to reflect in orange or red wavelengths in order to make bright and saturated colours, which cannot be produced using either biophotonic nanostructures or pigments alone.’

Not only have very similar barb structures evolved independently in many families of birds (at least 44) but these look very much like other nanostructures seen in the physical world, such as beer foam, corroding metal alloys, and oil-in-water. It suggests that, like these latter structures, feather nanostructures may have evolved by a process of self-assembly (the phase separation of keratin from the cytoplasm of the spongy barb cells).

‘This suggests that many lineages of birds have independently evolved to utilise the self-assembling properties of a polymerising protein in solution to create optical nanostructures,’ Vinod comments.

The findings feed into his current work with Ben Sheldon studying the ultraviolet light reflecting crown structural colour ornaments of blue tits, which males use to attract females and see off rival males:

‘By studying these non-iridescent barb structural colours across all birds, we have a better idea of the distribution of these colours across the evolutionary history of birds so that we can trace the evolution of barb structural colours in other birds closely related to the blue tits.

‘That these barb nanostructures could be self-assembled intracelllularly from beta-keratin, the most basic constituent of feathers, suggests that there may be little or no cost involved in producing such structural colours.’

Yet the secrets of structural colours aren’t just for the birds, they could also help to develop new materials for photonic devices that would not allow the passage of a certain band of wavelengths in any direction: such materials are currently hard to fabricate defect-free and on an industrial scale.

Vinod comments: ‘The nanostructures in bird feather barbs, that are likely self-assembled and have evolved over millions of years of selection for a consistent optical function, could be used to inspire novel photonic devices.

‘They could be used as biotemplates for the fabrication of photonic materials using better technological raw materials (such as titania or silica), or we can try and mimic their process of self-assembly using synthetic polymers for colour tuneable applications.’

So, in the not too distant future, we could be growing our own artificial feathers not just to dazzle and amaze but to harness the power of light.

A report of the research, 'Structure and optical function of amorphous photonic nanostructures from avian feather barbs: a comparative small angle X-ray scattering analysis of 230 bird species', is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Image: Diversity of non-iridescent or angle-independent feather barb structural colours in birds and the underlying nanoscale morphology of the colour-producing (photonic) nanostructures revealed using electron microscopy and synchrotron small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Credits: Collage by Vinod Saranathan, photograph of Plum-throated Cotinga (Cotinga maynana) by Thomas Valqui.

A new examination of silkworm cocoons suggests how they could inspire lightweight armour and environmentally-friendly car panels.

Scientists from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology studied 25 types of cocoons for clues to how the structures manage to be very tough but also light and able to ‘breathe’.

Fujia Chen, David Porter, and Fritz Vollrath report in Journal of the Royal Society Interface on their research into the factors that enable cocoons to protect their occupants.

‘Cocoons protect silkworms in the wild as firstly a hard shell, secondly a microbe filter and thirdly as a climate chamber,’ Fritz tells me, adding that this order of importance will change depending on the threats and environmental conditions faced by each species.

The lightness of cocoons is down to both the material they are made of – silk – and the way that this is turned into a layered composite material with a clever arrangement of silk loops that are woven together with gum only at the intersections.

‘By controlling the density of the 'weave' the animal controls the material properties of each layer, and by having different properties for different layers the animal can make tough yet light structures,’ Fritz explains.

‘In addition many wild silk worms integrate mineral crystals (which they obtain from their food plants) into the composite to give extra strength. Silk cocoons could bring inspiration to light-weight armour by showing ways that animals have solved some of the problems faced by human designers.’

At present most of the cocoons produced around the world are boiled and unravelled to be made into textiles, but the researcher suggest that they could be used to create composite materials that could satisfy the demand for car panels and other components in fast-growing economies such as India and China.

‘Silk cocoons are fully sustainable, non-perishable and climate-smart agricultural products,’ Fritz comments. ‘They are also very light, tough composites. Using cocoons as base materials, in combination with equally sustainable fillers should help us make sustainable composites with many layers of complexity.’

The next stage in the research will involve looking for natural glues and resins that interact well with mats of ‘raw’ (unwoven) cocoons.

Fritz adds: ‘This will require a good understanding not only of the cocoon materials but also of composite theory and the issues involved in turning that into practice.’

Ganymede as observed by the Galileo spacecraft

Ganymede as observed by the Galileo spacecraftIt’s official: it was announced today that Oxford University scientists will help to prepare a mission to Jupiter and its icy moons.

But whilst the JUICE spacecraft will beam back valuable data on several of the planet’s satellites, it will give special attention to one in particular: Ganymede.

I asked Leigh Fletcher of Oxford University’s Department of Physics, one of the JUICE team, about the appeal of Ganymede, what they hope to find there, and how Oxford scientists will probe the secrets of this enigmatic 'waterworld'…

OxSciBlog: What makes Ganymede so interesting?

Leigh Fletcher: When people think of moons in our solar system, they often imagine them as being inferior to the main planets, and somehow less interesting. The moons of Jupiter show how wrong that misguided assumption can be - the four largest Jovian moons (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto) are the size of planets, and each has a fascinating and rich geologic and chemical history.

These moons truly are worlds in their own right, with a diverse range of unusual landscapes and features that can keep scientists busy for decades. ESA has chosen to focus on Ganymede, the largest example of an icy moon in our solar system. It is thought to be made of roughly equal measures of rocks and water ice, and is likely to harbour a saltwater ocean beneath its icy crust. For those searching for habitable environments in our solar system, the mantra has always been to follow the water, as the vital solvent for the chemical reactions of life.

Ganymede's surface has a mixture of ancient, dark, cratered surfaces, and brighter water-ice-rich regions of ridges. The biggest feature is a dark plain called Galileo Regio, visible from Earth even through amateur telescopes, and may even have polar caps of water frost. Furthermore, Ganymede has an extremely tenuous oxygen atmosphere, and is the only moon in our solar system with a magnetic field, probably caused by convection within a liquid iron core.

OSB: How does it compare to Jupiter’s other moons?

LF: To better understand Ganymede, it's important to consider the processes which shaped its evolution and surface features by comparing it to the other Galilean moons: although these four worlds of fire and ice probably had the same origins in the Jovian sub-nebula, their present-day structure is the end of product of aeons of subsequent evolution. Jupiter's immense gravity causes tidal flexing of the moons (strongest at Io, weak or absent at Callisto), providing energy to liquefy the water ice crusts and produce internal activity.

Io is mostly rocky, lacking the water ice of the other satellites but featuring hundreds of active volcanoes. Europa is the smallest of the four, with a smooth geologically-young icy surface overlying a water ocean, heated by the tidal flexing from Jupiter. Ganymede's ocean is likely to be deeper than Europa's, under a thicker ice crust. Callisto is further away and experiences less tidal heating, resulting in an ancient terrain, one of the most highly cratered surfaces in the solar system.

OSB: What do we hope JUICE will find out about it?

LF: JUICE will be the first orbiter of an icy moon, and provide a full global characterisation of its surface composition, geology and structure. An ice-penetrating radar will peer through the icy crust for the first time, providing us with our first access to the water ocean of a Galilean moon. Our key goal is to assess the potential habitability of Ganymede as a representative of a whole class of ‘waterworlds’ which may exist around other stars, building upon the discoveries of habitable environments on the Earth's deep ocean ridges.

So JUICE will be looking for key characteristics of habitability on Ganymede - sources of energy, access to crucial chemical elements, liquid water, and stable conditions over long periods of time.

It's a crucial step in our reconnaissance and exploration of our solar system, and towards answering the question of 'What are the necessary conditions that make a planetary body habitable?’ By comparing the three potentially ocean-bearing Galilean moons, we hope to identify the physical and chemical characteristics driving the evolution of this planetary system.

JUICE will study the extent of Ganymede's ocean, its connection to the deep interior and ice shell; the global distribution and evolution of surface materials, geologic features, and present-day surface activity; and the interaction with the local environment and magnetosphere. In addition, JUICE will explore recent activity and composition on Europa, and characterise Callisto as a remnant of the early Jovian system. Finally, JUICE will be capable of exploring the wider Jovian system, from the complex and dynamic Jovian atmosphere, the magnetosphere, the minor satellites and rings.

OSB: What instruments will be needed to study it?

LF: The proposed JUICE payload has cameras to take images of the icy moon surfaces and swirling Jovian clouds; spectrometers covering ultraviolet, near-infrared and sub-millimetre wavelengths to determine moon compositions and temperatures, winds, composition and cloud characteristics on Jupiter; a magnetometer and plasma instruments to conduct an investigation of Jupiter's magnetosphere; and a laser altimeter, ice-penetrating radar and radio science instrument to probe below the surface of the Galilean moons and through the Jovian cloud decks.

The payload is just a model right now, and other instruments could be added. All this will be launched on a 5 tonne spacecraft in 2022, with solar arrays to provide power and a large high-gain antenna to return the data to Earth. It will take 7.5 years to reach the giant planet, before going into orbit around Jupiter to conduct an extensive survey of the whole planetary system. Then, in the final phase in 2032, it will enter orbit around Ganymede.

OSB: How are Oxford scientists likely to contribute?

LF: Oxford has a strong heritage of contributing instrumentation and data analysis techniques for outer solar system missions, notably with the near infrared mapping spectrometer (NIMS) on Galileo and the composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS) on Cassini.

We also have a long-term campaign of giant planet studies from ground-based observatories in Hawaii and Chile and space-borne telescopes (Spitzer, Herschel, Hubble). This has allowed us to contribute to the science case for a return mission to Jupiter and its icy moons, identifying the key questions and mysteries left unanswered by previous generations of spacecraft.

Oxford, along with many other UK institutions, will hope to contribute instrumentation to fly to Jupiter to address some of these questions. Involvement with Galileo and Cassini enabled Oxford to build up a rich planetary science group, with a broad range of experience from lab spectroscopy to spacecraft hardware, and from icy moons to gas giant dynamics. This expertise will help us to solve the challenges of the JUICE mission.

OSB: What is the next big milestone for the JUICE mission?

LF: Now that the mission has been officially selected by ESA as the L-class mission for 2022, the hard work really begins. Industry will be invited to design and build the spacecraft systems, and an announcement of opportunity will be issued to call for instrument designs. Teams will be assembled to thrash out ideas for instruments that address key scientific questions, all hoping to see their particular design on the launch pad when we lift off for Jupiter in a decade's time.

The final go-ahead for the mission from ESA, known as 'adoption', should come in the next 2-3 years.

Exactly what sort of headgear do sub-atomic particles wear?

This is one of the important issues addressed in an animation about the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the first offering from Oxford Sparks, a new portal giving people access to some of the exciting science happening at Oxford University.

In search of the science behind the fun, I asked Alan Barr of Oxford University’s Department of Physics, who works at the LHC, about his role as scientific adviser on the animation and coping with a cast of prima donna protons…

OxSciBlog: Why do you think we need an animation about the LHC?

Alan Barr: The Large Hadron Collider is one of the inspirational science experiments of our time, but it can be difficult for a non-expert to understand what it is about. Anything which helps make the science accessible - even as a first taste - is a good idea as far as I’m concerned. So when the OxfordSparks team suggested using ‘A quick look around the LHC’ as a pilot for OxfordSparks.net, I happily agreed to help advise on the science side.

OSB: What contribution did you make to the LHC nugget?

AB: I wish I could say I’d done the animation – but thankfully the hard bit was done by Karen Cheung, a really impressive professional animator from the company Jelly. My role as scientific consultant was to try to make sure that, as well as being great fun, the cartoon conveyed as much physics as possible, and as accurately as possible. Of course that’s a bit tricky in a cartoon. Protons don’t really wear crash helmets, and the Higgs boson doesn’t really have a flower in his hat, even if he appears to in the cartoon. But we were able to illustrate the basic ideas of what happens at CERN - the acceleration, the collisions and the detection of new particles.

OSB: What concept are you most proud to see in the finished animation?

AB: When particles move close to the speed of light, the effects of Einstein’s relativity are really important. Very fast particles get heavier, and so our character - Ossie - starts feeling rather bloated as he gets accelerated. Later on, when the protons collide, their energy is turned into new, exotic particles - again just as predicted by Einstein and as we observe in the collisions at CERN.

We’ve also put together some extra information on the OxfordSparks web page describing a little more background about how the accelerator works, and the role that Oxford played in the construction and operation. We explain, for example, how we one can detect the characteristic signals we expect from exotic new particles like Mr Higgs.

OSB: What feedback have you had from fellow physicists/the public?

AB: I emailed an early version of the animation to some of our own graduate students here in Oxford. As soon as I heard their laughter coming down the corridor I knew that we were onto a winner. After we released it on YouTube the uptake was fast… I’ve just had a peek at the YouTube page and there have already been more than 27,000 views, so it’s clearly caught the public imagination. We’ve also had interest from other LHC scientists around the world… so who knows – we may even end up going international, just like the LHC itself.

You can like Oxford Sparks on Facebook, follow on twitter or visit at YouTube.

Scientists studying the calls made by killer whales and pilot whales have a big problem: these whales talk too much.

Because they make so many different sounds it is very hard to work out what these noises might mean. A first step would be to understand the typical sounds these animals make, and that’s where volunteers visiting Whale.FM can help.

Robert Simpson of Oxford University, one of the researchers behind the project, told Scientific American’s Mariette DiChristina:

‘When you visit Whale.FM, you are presented with a sound clip of a recording of a whale. The idea is to match the big sound that you see/hear with one of the smaller ones underneath.

‘All the pairings go into a database and we use that to find the best pairs of sounds and build up our understanding of what the whales are saying to each other. Basically: we need help decoding the language of whales.’

Whale.FM is the latest in a series of ‘citizen science’ projects led by or involving Oxford University scientists (others include Old Weather, Ancient Lives, and Galaxy Zoo) and is a collaborative effort of Scientific American, Zooniverse and the research institutions WHOI, TNO, the University of Oxford, and SMRU.

One of the questions always raised by citizen science projects is whether volunteers can perform tasks as well as professional scientists. To test this the team took a selection of calls where they already knew the call category and tested them against the groupings given by people visiting the site.

‘We found that the Whale.FM volunteers grouped up the sounds in the same way that professionals would,’ Robert comments. ‘It agrees very well. We found approximately 90 percent agreement in our preliminary test. Our volunteers are amazing!’

Perhaps the biggest surprise, he says, is that their results could be used to help improve automated algorithms for decoding whale sounds:

‘There are tens of thousands of whale calls out here. It would seem that Whale.FM can help narrow the big problem into a smaller, more manageable one.’

- ‹ previous

- 189 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria