Features

The Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology is an international centre of excellence for researching inflammation in the body, from causes to treatments. Professor Irina Udalova is the Institute's principal investigator of the genomics of inflammation. Her latest research has found that a protein known as Interferon Lambda Two (IFN-λ2) could restrict the development of debilitating inflammation, like that found in rheumatoid arthritis.

I spoke to her about the research and what it might mean for people with rheumatic diseases.

OxSciBlog: What are interferons and what do they do?

Irina Udalova: Interferons (IFNs) are a group within the large class of proteins known as cytokines, which are used by the immune system for communication between cells, in particular during microbial infection. They are probably most famous for their ability to interfere with viruses and protect cells from viral infection, but they have other immune functions as well.

OSB: Your latest paper looks at a protein called Interferon Lambda Two (IFN- λ2). What prompted you to look at this particular protein?

IU: We have been interested in the IFN-lambda system and in particular its possible role in inflammation since its original discovery in 2003. Our first venture in to the field was about IFN-lambda gene regulation and production. In 2009 we published a paper describing how the expression of the IFN-lambda 1 gene is regulated in human dendritic cells, which are the main producers of it.

Cytokines are proteins released by cells in response to environmental challenges to communicate with other cells. Interferon lambda is part of the type II cytokine family, which include other interferons, such as IFN-alpha, beta and gamma, but also interleukin 10 (IL-10), a cytokine famous for its anti-inflammatory effects. Interferon lambda has structural similarities to both IFN-alpha and beta and IL-10.

We have always hypothesized that being related to IL-10, IFN-lambdas may also have anti-inflammatory activity However, progress was hampered by the lack of good antibodies to the receptor and some uncertainty in the field as to what immune cells actually respond to IFN-lambda, making it difficult to detect.

OSB: How did you investigate the effects of IFN- λ2?

IU: We teamed up with the researchers at a firm called Zymogenetics who provided us with mice lacking IFN-lambda receptors – their cells could not be affected by IFN-lambda. The company also supplied recombinant IFN-lambda protein.

We used collagen to induce arthritis in the mice. Known as collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), this is considered to be a gold standard animal model of human rheumatoid arthritis. We either treated the mice with recombinant IFN-lambda at the first sign of arthritis or we left them untreated.

OSB: What were the results?

IU: To our great surprise, the first experiment with IFN-lambda treatment showed a complete reversal: The arthritis was halted and the joints of treated mice remained intact while the untreated mice developed severe inflammation, cartilage destruction and bone erosion.

We did many more experiments figuring out the right doses of the treatments as well as trying to understand how this protection works at the molecular level. It took us a couple of years of going through various possible cell types to find out that the main immune cells targeted by IFN-lambda were neutrophils.

OSB: What are neutrophils?

IU: Neutrophils are the cells in the very beginning of the inflammatory cascade. They recognise tissue injury or pathogens and begin digesting and destroying the invading microbes. They also send signals to other cells of the immune signal to come aboard, thus leading to a cascade of further immune reactions.

The role of neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases have been somewhat understudied as they are believed to have a very short life span. However, recent evidence suggest that they may live for much longer if activated and they contribute to shaping the immune response and associated effects on the body. In some other models of experimental arthritis, removing neutrophils prevents the disease.

IFN-lambda seems to prevent neutrophils moving to the site of inflammation, without significantly affecting their numbers in the blood. This is important, as it indicates the lack of toxicity and adverse effects.

OSB: What’s next?

IU: We do not know the exact molecular mechanisms behind these events. We plan to investigate those as well as examine other known properties of neutrophils and how treatment with IFN-lambda affects those.

Our immediate focus is on rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases where neutrophils play a part in disease development, such as vasculitis or gout.

Also most of our work has so far been done in a model system. We would like to validate the findings in human neutrophils and explore the possibility of re-purposing IFN-lambda (which is now in clinical trials for hepatitis C treatment) for inflammatory diseases.

Four times a year, OUP's free online dictionary OxfordDictionaries.com updates its list of words.

In the latest list of additions, announced today, there are a number of words used mainly by young people, often referring to food, drink and technology.

'New words, senses, and phrases are added to OxfordDictionaries.com when we have gathered enough independent evidence from a wide range of sources to be sure that they have widespread currency in the English language,' said Angus Stevenson of Oxford Dictionaries.

'This quarter's update shows that contemporary culture continues to have an undeniable and fascinating impact on the language.'

In a guest post, Kirsty Doole from Oxford Dictionaries takes us through some of the new entries:

'Today Oxford University Press announces the latest quarterly update to OxfordDictionaries.com, its free online dictionary of current English. Words from a wide variety of topics are included in this update, so whatever your field of interest, everyone should find something they think is awesomesauce.

Food and drink have provided a rich seam of new words this quarter, so if you’re feeling a bit hangry then pull up a chair in your local cat cafe or fast-casual restaurant and read on (but if you’re in the mood for something sweet then make sure they won’t charge you cakeage). Why not try some barbacoa or freekeh? As for something to drink, if it’s not yet wine o’clock, then you could dissolve some matcha in hot water to make tea.

The linguistic influence of current events can be seen in a number of this update’s new entries, from Grexit and Brexit to swatting. We also see the addition of deradicalization, microaggression, and social justice warrior.

Technology and popular culture remain strong influences on language, and are reflected in new entries including rage quit, Redditor and subreddit, spear phishing, blockchain, and manic pixie dream girl.

How we consume information is exemplified by additions such as glanceable, skippable, and snackable. This quarter also sees the addition of the words mecha, pwnage, and kayfabe.

Other informal or slang terms added today include NBD (an abbreviation of ‘no big deal’), mkay, weak sauce, brain fart, and bruh. Several modern irritations take their place in OxfordDictionaries.com today: who can fail to be annoyed by manspreading, pocket dialling (or butt dialling), or those instances where you MacGyver something and it doesn’t quite work. Never mind, ignore the randos, and go home and cuddle up with your fur baby.

Don’t get butthurt about our bants! Research by the Oxford Dictionaries team has shown that all of the words, senses, and phrases added to OxfordDictionaries.com today have been absorbed into our language, hence their inclusion in this quarterly update. Mic drop.

The full meanings of these words, and the other additions, can be found at OxfordDictionaries.com.

Imagine designing and mass-producing nano-sized objects that can interact with molecules and human cells with incredible precision. The structures would be precisely engineered to deliver drug therapies custom-fitted to each patient, or even bind to cancer cells to keep them from reproducing. Imagine being able to deploy a tiny device made of DNA that can detect the presence of a molecule that indicates a major health problem and release a drug.

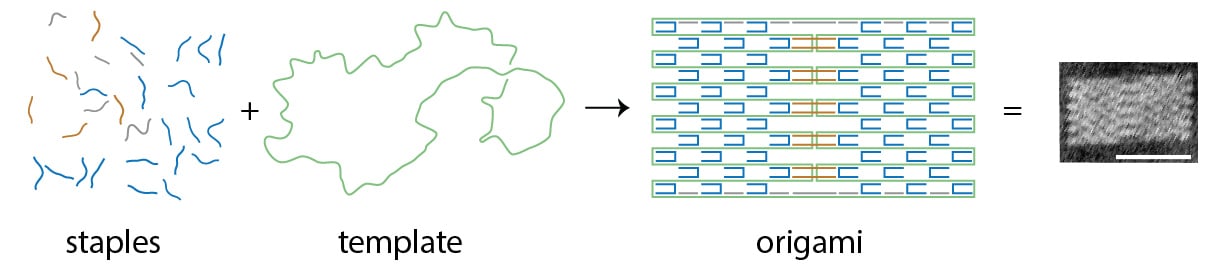

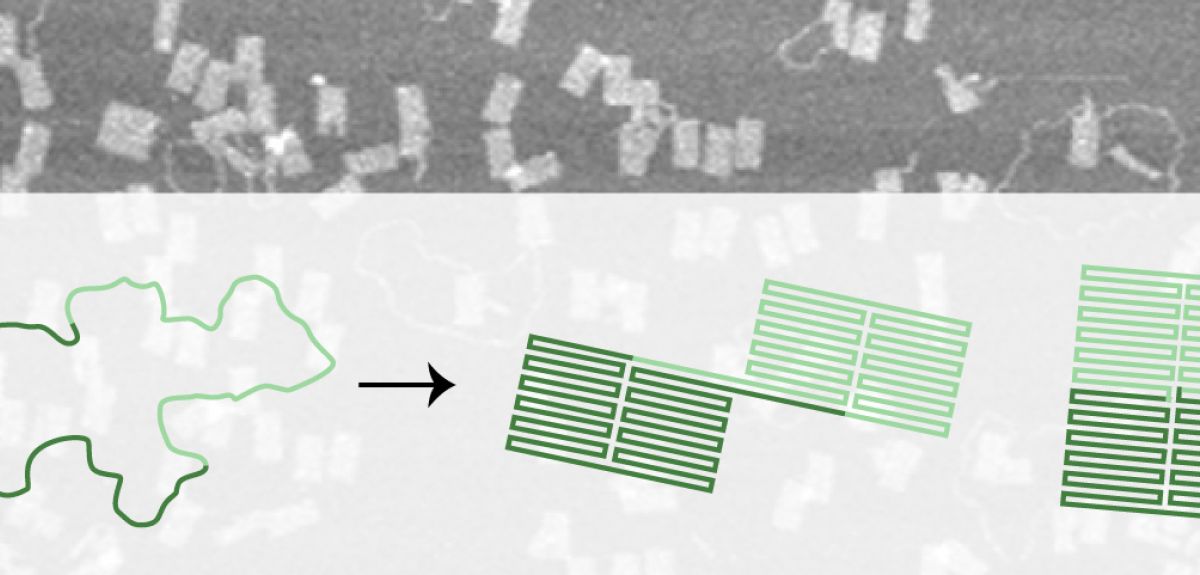

While these sorts of technologies are still a long way off, the process of designing them is advancing rapidly thanks to improvements in DNA origami technique. Nearly ten years ago, researchers first described a technique to fold a long single strand of DNA into various two- and three-dimensional shapes including a smiley face and three-dimensional cubes. The shapes are created by adding multiple small 'staple' strands of DNA to the template strand, gathering and doubling up the strand many times over as the mixture is combined, heated and then cooled in a buffer of salt water. Each drop of stapled DNA mixture contains around 1012 copies of each template strand and staples – if all goes to plan the result is 1012 identical DNA origami shapes. But it doesn’t always turn out that way.

'It is remarkable how well DNA origami works - in fact, it is remarkable that it works at all,' says Jonathan Bath, who is part of the biological physics group in Oxford’s Clarendon Laboratory. 'DNA origami is a reliable technique, if you design a simple structure you can expect a good fraction of your origami to be well-folded but as you increase the complexity of your design (for example when you go from two dimensions to three), the fraction of well-folded origami can fall dramatically.'

The way in which DNA strands and staples combine to form increasingly complex structures can be seen as both predictably obvious and confusing. DNA is a useful construction material because of the predictable way its base pairs join together. Its nucleotide bases Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T) form complementary A-T or C-G bonds, which means pairing staple DNA sequences in the right order to match a specific region of the template strand will produce predictable bonds that then produce shapes. Sections that are designed to bind together are given complementary sequences; other sections are given sequences that are as different as possible to minimize unintended interactions. What’s less obvious is how and why the stapled strands fold in sequence into well-formed shapes rather than just collapsing or mis-folding.

'Even the process of creating relatively simple DNA origami shapes produces a certain amount of mis-folded shapes,' Bath notes. 'As DNA origami structures get more sophisticated the technique becomes less reliable, and we end up with more mis-folded or tangled shapes that have to be separated out from the well-folded shapes we want to produce. If we want to fix this then we need to understand the folding. If we can fix it then we can continue to make increasingly sophisticated structures by guiding the folding pathways towards well-folded shapes and steer the system from becoming trapped in mis-folded shapes.'

This folding pathway is what Bath and his colleagues have investigated in a paper just published in Nature. Their goal, he emphasises, was not to make a 'new and improved' DNA origami structure but to design a system that would help to understand the mechanism that makes DNA origami fold in the way that it does. 'Often the first step towards understanding a system is to try and break it,' he explains, 'so we designed a DNA origami that has a handful of well folded-shapes but an overwhelmingly large number of misfolded states to trap the system.'

Remarkably, rather than breaking the DNA folding mechanism, Bath’s experiment still produced a surprising number of well-folded shapes. The result, he says, demonstrates the existence of folding pathways that steer the system towards well-folded shapes through a vast folding landscape littered with traps. ‘In any given experiment, we observe a mixture of well-folded shapes, some shapes more abundant than others,’ he explains. ‘The mixture serves as a record of events that take place along the folding pathway, it we tweak the folding pathway then the distribution of shapes that we observe will change.’

The experiment reveals that there are rules that govern the folding of DNA origami – if these rules are incorporated into future designs then they should make the production of complex DNA structures more successful. But the goal of the experiment wasn't just about improving DNA origami structures, but understanding them. 'Simple DNA origami folds well, so from a technology point of view, there is no problem,' says Bath. 'But from a science point of view there is a problem – we do not understand how it works and we would like to understand.'

'For me, the motivation comes from looking at biological systems: they are full of molecular machines –machines that read and copy information, join and break molecules, shuttle cargo from one place to another and so on. At least in principle, there is no reason why we should not be able to build our own machines to tackle similar tasks but this is a tall task and we’ll have to start simple. DNA nanotechnology (of which DNA origami is a subset) offers a realistic route towards the design and construction of molecular machines. If we are serious about achieving those ambitious goals then we need to understand what we are doing.'

The full report in the journal Nature is co-authored by Katherine Dunn, Jon Bath, Andrew Turberfield, Tom Ouldridge, Frits Dannenberg and Marta Kwiatkowska from Oxford University.

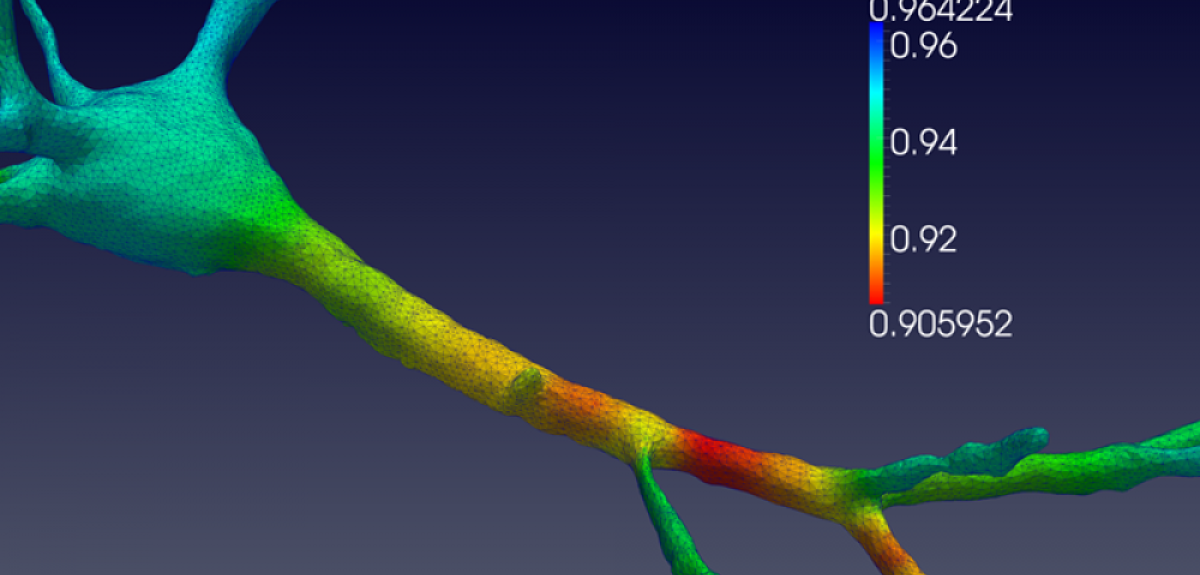

The International Brain Mechanics and Trauma Lab (IBMTL) has been running since the beginning of 2013. Its partnership of 26 academics in 15 locations is not unusual. What is striking is the breadth of disciplines from which they are drawn.

IBMTL doesn’t just bring together the various medical disciplines with an interest in the brain, it includes biologists, physicists, engineers, mathematicians and computer scientists.

The power of the programme is the collaboration of experts from different disciplines to study brain cell and tissue mechanics and how they relate to brain functions, diseases or trauma.

In this video, IBMTL directors Professors Alain Goriely and Antoine Jérusalem explain more about the work of their international collaboration.

Gels are useful: we shave, brush our teeth, and fix our hair with them; in the form of soft contact lenses they can even improve our eyesight.

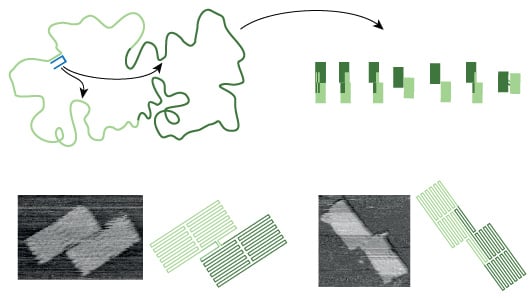

Recently, researchers at Oxford University’s Department of Engineering Science have been investigating ‘smart gels’ that can switch from a stable gel to a liquid suspension of very small particles (a ‘sol’).

Now they report in the journal Advanced Materials that they have discovered a new family of gel-like materials whose behaviour is extremely unusual; not only is their ‘shape-shifting’ from gel to sol entirely reversible but it can be triggered by a range of stimuli including heat, mechanical pressure, and the presence of specific chemicals.

So what makes these new smart gels so smart?

The gels are actually hybrid materials that assemble themselves from metal and organic components, explains Abhijeet Chaudhari, a DPhil student in the Multifunctional Materials & Composites (MMC) Laboratory at Oxford University's Department of Engineering Science, who is the first author of the report.

‘When we scrutinised the hybrid gels under a scanning electron microscope (SEM), we were astounded to see exquisite fine-scale fibre architectures, which are completely different from those known in any other contemporary gel materials,’ Abhijeet tells me.

SEM images (false colour) depicting the intricate gel fibre architecture

SEM images (false colour) depicting the intricate gel fibre architecture

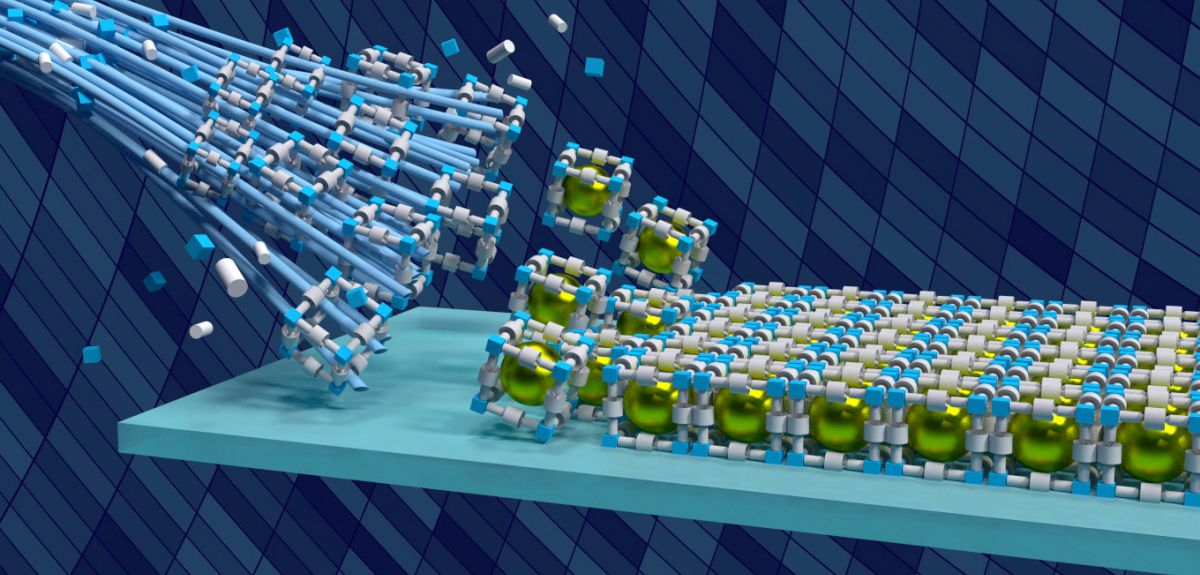

They then discovered that intertwined amongst these microscopic fibres were a profusion of nanoparticles around 100 nanometres in size. An X-ray diffraction technique confirmed that these were nanoparticles of ‘HKUST-1’, a copper-based Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) notable for its very large surface area (exceeding 2000 square-metres in each gram).

Professor Jin-Chong Tan of the Department of Engineering Science, who led the team, says: ‘Because of its fine-scale fibre network architecture, which is hierarchical in nature, the new hybrid gels are remarkably sensitive to different combination of external stimulants.’

Reversible conversion of a hybrid gel subject to physical and chemical stimuli

Reversible conversion of a hybrid gel subject to physical and chemical stimuli

‘This makes this family of hybrid gels highly tuneable, enabling us to engineer bespoke materials with the desired properties to fit a specific application,’ adds Abhijeet.

To illustrate this, the team demonstrated that by simply switching the types of solvent used in material synthesis the electrical conductive properties and mechanical resilience of the gels can be altered.

The tuneable properties of these materials come from the sol-gel transformation in which an apparently stable gel collapses into a sol and then become a gel again once the external stimuli are removed. This behaviour is driven by what is happening inside the material at the microscopic scale where there is rapid molecular bond-breaking (gel to sol) and bond–making (sol to gel).

Jin-Chong says: ‘This fascinating phenomenon is exceptionally rare for gel systems incorporating MOF nanoparticles; to the best of our knowledge this is the first example of its kind reported in the literature.’

Such shape-shifting materials could find applications in Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS) and NEMS devices. They could also create ‘self-healing’ coatings that can repair themselves after impact or corrosion damage or in energy technology to build new electrolytes for rechargeable batteries or enhanced dielectrics for supercapacitors.

But it’s the promise of MOF nanoparticles suitable to make into thin films for sensors and microelectronics that is particularly alluring.

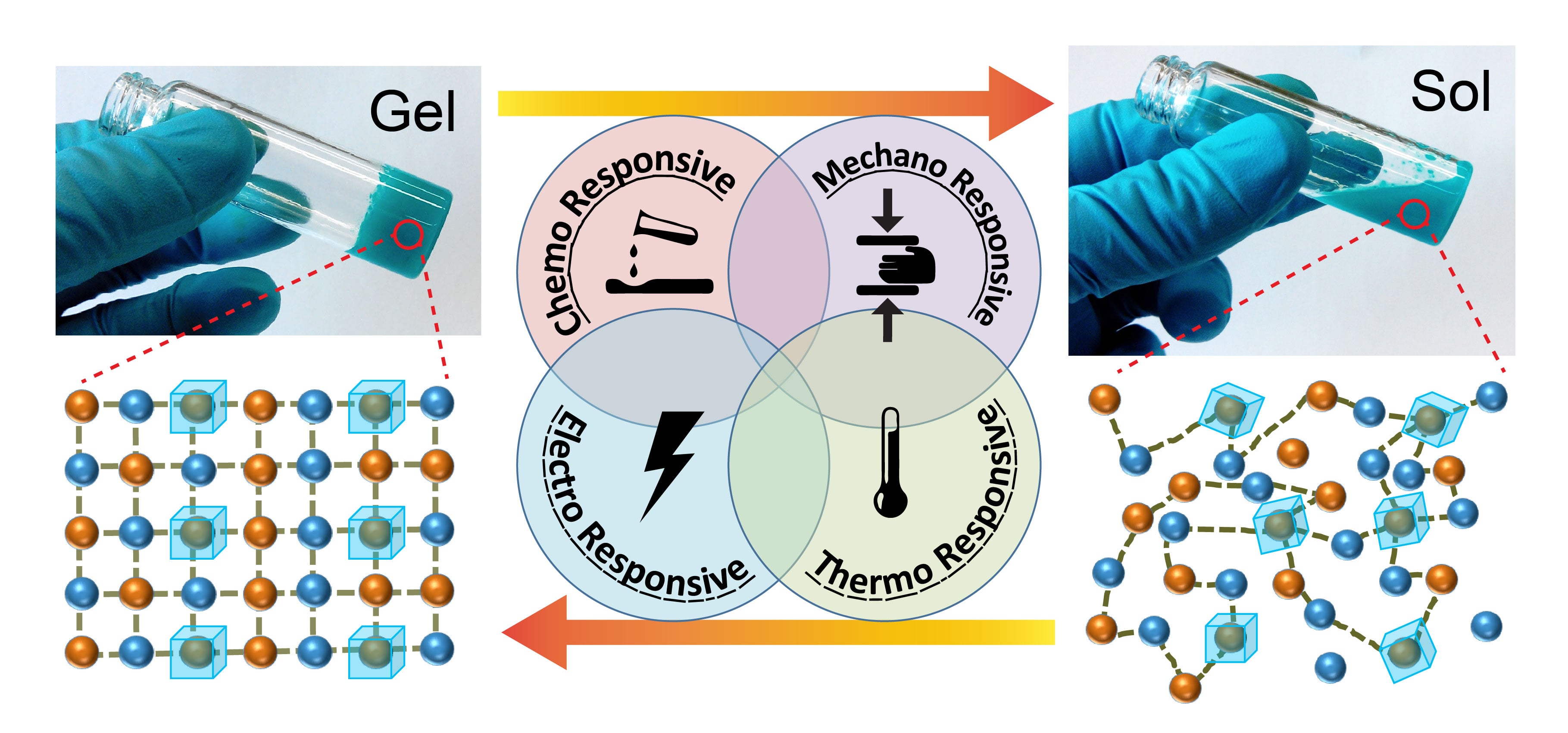

Abhijeet explains that conventional methods of MOF thin film fabrication are costly, laborious, and mostly limited to creating small surface areas, making them unsuitable for large-scale commercial use: ‘We discovered that copious amounts of high-quality HKUST-1 (MOF) nanoparticles can be straightforwardly harvested by breaking down the gel fibres using methanol.’

‘These MOF nanoparticles can then be used as a ‘precursor’, making it easy to fabricate multifunctional thin films on various substrates. These thin films can, for instance, function as a coupled temperature-moisture sensor that rapidly switches from turquoise to dark blue colour for easy identification, reversibly, upon heating.’

Thin film sensors created using MOF nanoparticles harvested from hybrid gels

Thin film sensors created using MOF nanoparticles harvested from hybrid gels

The team worked with Isis Innovation to patent the technology and Samsung Electronics, who part-funded the research, are looking to translate this discovery into a range of real-world applications including optoelectronics, thin-film sensors, and microelectronics.

‘We believe our method has huge potential,’ comments Jin-Chong, ‘it opens the door to exploiting MOF-based supramolecular gels as a new 3D scaffolding material useful for engineering optoelectronics and innovative micromechanical devices.’

In the future, it seems, smart gels could lead to some very smart technology.

- ‹ previous

- 146 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria