Features

When will this all be over? As the number of COVID-related infections, hospitalisations and deaths reported in the UK continues to fall, the chorus grows ever louder for the abandonment of restrictions on everyday activity.

Summer holidays in Spain, crowded sporting arenas and nightclubbing, are held out as examples of normal life to which we can look forward. But, for many, it is the more mundane life they miss: meeting friends and relations indoors, having a coffee in a coffee shop, going to the library or cinema.

But the question of when the pandemic (or epidemic) is over is not as simple as it might appear. It is a medical question, but determining what is an epidemic and when it has ended is also a political and social question.

In the past, epidemics have ended in a variety of ways...sometimes the illness has gone but sometimes people have learned to live with it

In the past, epidemics have ended in a variety of ways – some in which the illness has gone and others in which it has not, but people have learned to live with it.

Oxford Historian Dr Erica Charters is leading a project looking at these complex questions. Some 40 researchers, from more than a dozen universities across the academic spectrum, have come together to study - ‘How Epidemics End’.

The team includes experts in a variety of past events which have wreaked havoc around the world – from the plague to TB to HIV/AIDs to cholera.. And this week the team is releasing a series of videos discussing what has happened in past epidemics. The first three videos compare how different researchers study cholera and its ending, explaining the cholera epidemics which devastated countries including England in the 19th century, but more recently, Yemen.

‘We have asked the question: how did epidemics end?’ says Dr Charters. ‘We have brought together longer term reflections on this and looked at the different ways of distinguishing the end – looking at epidemiological and mathematical models alongside political and social questions.

’But there is no one answer. Everyone wants certainty and answers but it is not just a decision about a disease but a political decision: what will people live with?’

Everyone wants certainty and answers but it is not just a decision about a disease but a political decision: what will people live with?

Dr Erica Charters

In January, Dr Charters and Dr Kristin Heitman wrote, ‘Detailed research on past epidemics has demonstrated that they do not end suddenly; indeed, only rarely do the diseases in question actually end.’

Dr Charters points out, ‘In the past, epidemics have ended in one of three ways.

‘People begin to live with it [influenza]. It moves to another part of the world [the plague] or it is managed through medical treatment and no longer seen as an epidemic in that part of the world [HIV/AIDs].’

As the numbers of infections continue to fall in the UK, although other countries are still experiencing severe illness, COVID appears to follow the pattern. But Dr Charters warns against ‘false endings’. And the historian, who specialises in the history of medicine, points out that some diseases may be considered an epidemic in some parts of the world but may be common elsewhere, ‘Malaria is endemic in large parts of Africa but if there were cases in England, it would cause alarm.’

People begin to live with it [influenza]. It moves to another part of the world [the plague] or it is managed through medical treatment and no longer seen as an epidemic in that part of the world [HIV/AIDs]

It is this sense of alarm which underpins the pandemic (which is an epidemic on a global scale). The January paper maintains, ‘Epidemics—like the recurring narratives they produce—throw a society's confusion, fears, and anxieties into high relief.’

It continues, ‘When communities are thrown into panic and turmoil by the outbreak of a new disease, when medical committees are convened and central governments spring into action, epidemics are understood in clear biological terms.... But at the end stages of epidemics, the disease is regarded through the filter of political, social, and economic dislocation—dislocations that have deepened as the epidemic progressed—articulating the processes by which policy decisions are debated and implemented, and the accommodations between scientific models and human behaviour.’

The World Health Organisation categorises it as a public health emergency of international concern. But, from a global perspective, it means different things to different groups at different times – not just as the disease spreads around the world but because within the same country, different groups will experience a disease differently.

So the end will also be different for different peoples. Dr Charters says, ‘It is unlikely that there will be a single end date.’

There may be biological markers, suggesting a decline in infections or excess deaths. People tried to track these in 17th century England, when the number of plague deaths fell and the population returned to London – rather prematurely.

But, says Dr Charters, in general, the end of epidemics can be traced to ‘when people resume social practices’. She adds, ‘When the city gates opened and groups returned.’

In general, the end of epidemics can be traced to when people resume social practices. When the city gates opened and groups returned

And she notes, there is also a falling off of evidence – as people stop recording the impact of the disease and go back to their previous occupations.

According to the article ‘How epidemics end’, ‘Epidemics end once the diseases become accepted into people's daily lives and routines, becoming endemic—domesticated—and accepted. Endemic diseases typically lack an overarching narrative because they do not seem to require explanation. More often, they appear as integrated parts of the natural order of things.’

But, says Cr Charters, one of the research team points out that there have just as often been celebrations and thanksgiving to mark the end of epidemics - that they have not just fizzled out.

Endings were not always quiet,’ she says. ‘There have been celebrations and fireworks, thanksgiving...but most epidemics have ended when people just returned to their lives.'

See the videos here How epidemics end | How Epidemics End (ox.ac.uk)

Professor Gascia Ouzounian

Contemporary art is replete with works which explore the relationships between sound and space, with ‘space’ understood in physical, sensorial, geographical, social, and political terms.

Today, I can plug my headphones into the façade of a building in Berlin called BUG, to hear how its materiality, made audible through the use of seismic sensors in the building’s infrastructure, changes over time and in response to atmospheric variations, weather and other environmental factors. In other words, I can listen to a building as it evolves over time and in relation to its surroundings.

I can listen to a building as it evolves over time and in relation to its surroundings

In suburban London, I can visit Vex, a building whose spiralling form is inspired by the music of Erik Satie and the methods of John Cage.

Electronic music, projected over loudspeakers, is played throughout the building. It is created from sounds recorded during the making of the building itself: the sounds of breaking ground, of pouring concrete. This literal musique concrète is lush and surprisingly beautiful. It is impossible to say where music begins and architecture ends.

In 2017, I could visit Silent Room, an acoustic refuge in a low- income neighbourhood in Beirut. This temporary structure, erected in a parking lot close to a highway, used acoustic panelling to reduce environmental noise, but it also featured a quiet, meditative soundtrack composed of everyday city sounds. The designer wanted to draw attention to the uneven ways in which noise affects rich and poor inhabitants of the city - how a politics of noise shapes the city and differently impacts upon the lives of its residents.

While these particular projects are formed at the intersection of music, art, architecture and urban design, many others take the form of sound recordings, compositions, performances, films, installations, sculptures, radio works, websites, and much more.

Today, I can take a listening tour of Bonn, following a map of unique acoustic features of the city created by Bonn’s ‘City Sound Artist’ in 2010. Or, I can take an ‘electrical walk’ in any number of cities while wearing specially designed headphones which make audible normally inaudible elements of urban infrastructure. During my walk, formerly silent objects such as surveillance cameras, ATMs, and transportation infrastructures, beat and resonate with the pulses and tones of electromagnetic energy.

Despite this striking profusion of creative work and research that takes place at the intersection of sound and space, our historical understanding of how sound came to be understood as spatial remains lacking. Today we take for granted that sound is spatial, and that hearing is spatial: that it is possible to hear where sounds come from and how far or close they are.

Today we take for granted that sound is spatial, and that hearing is spatial: that it is possible to hear where sounds come from and how far or close they are

However, as recently as 1900, a popular scientific view held that sound itself could not relay ‘spatial attributes’, and that the human ear had physiological limitations which prevented it from receiving spatial information. Many psychologists believed it was through reasoning, or visual or haptic sensations, that an ‘auditory space’ was constructed.

In order to explore such striking shifts in perspective, Stereophonica: Sound and Space in Science, Technology, and the Arts (MIT Press) traces a history of thought and practice related to acoustic and auditory spatiality as they emerge in connection to such fields as philosophy, physics, physiology, psychology, music, architecture, and urban studies.

In the work, I track evolving ideas of acoustic and auditory spatiality (the spatiality of sound and hearing); and ideas that emerged in connection to particular kinds of spaces, acoustic and auditory technologies, musical and sonic cultures, experiences of hearing, and practices of listening.

My discussion begins in the 19th century, when scientists began systematically to study the physiology and psychology of spatial hearing. It extends to the present day, when sound artists seek to reconfigure entire cities through sound, and the concept of ‘sonic urbanism’ circulates within and across the worlds of architecture, urban studies and sound studies. Rather than trace a linear trajectory through any one historical route, I revisit a series of historical episodes in which the understanding of sound and space were transformed:

- the advent of stereo and binaural technologies in the 19th century;

- the birth of acoustic defence during the First World War;

- the creation of new stereo recording and reproduction systems in the 1930s;

- sonic warfare in the Second World War;

- the development of ‘spatial music’ and sound installation art in the 1950s and 1960s;

- innovations in noise mapping and sound mapping; and

- emergent modes of sonic urbanism (ways of understanding and engaging the city in relation to sound).

Each of these phenomena represents a distinct shift in how sound is created, experienced or understood in relation to space. Further, each sheds light upon evolving acoustic and auditory cultures, ways of listening, and changing ontologies of sound and space.

My aim is to cut into and across normally distinct histories, in order to show how various conceptions of acoustic and auditory spatiality have evolved over time and in connection to one another

By focusing on such transformative episodes, whether they last several years or several decades, my aim in Stereophonica is to set into dialogue various realms of thought and practice that bear upon contemporary ideas of acoustic and auditory spatiality, but that are normally kept distinct within such disciplines as philosophy, physics, engineering, music, and urban studies.

My aim is to cut into and across normally distinct histories, in order to show how various conceptions of acoustic and auditory spatiality have evolved over time and in connection to one another.

I therefore devote considerable attention to experimental projects, whether in science, music, art, or their interstitial spaces - including experiments that failed, were limited in their scope, had troubling ethical implications, or simply did not ‘succeed’ in entering mainstream discourses and canons, but that are nevertheless important because of their conceptual, technical, and aesthetic innovations.

It is within these experimental practices, those that test the boundaries of a field, that I find particular interest, especially with respect to ideas that defied conventional thinking and, in some cases, put wider social or cultural conventions under pressure.

In contrast to discourses that understand ‘space’ as a void to be filled with sound, my discussion shows that acoustic and auditory spaces have never been empty or neutral, but instead have always been replete with social, cultural, and political meanings. The case studies are chosen to reflect a particular progression both within and across them: how spatial conceptions of sound and hearing were hypothesised, codified, problematised, and politicised.

Stereophonica reveals how different concepts of acoustic and auditory space were invented and embraced by scientific and artistic communities, and how the spaces of sound and hearing themselves were increasingly measured and rationalised, surveilled and scanned, militarised and weaponised, mapped and planned, controlled and commercialised - in short, modernised.

Professor Gascia Ouzounian is a musicologist with the Oxford Faculty of Music and a member of Lady Margaret Hall.

Concerns over missed education for young people have spread around the world with schools and colleges firmly shut for long stretches because of COVID-19. In England, the Government has announced large-scale funding to help education recover from the devastation of the pandemic. As part of this, the very youngest children, who have poor oral language skills and have been particularly affected by the switch to online learning, will be able to access specialised help – key to academic success.

It is widely recognised that language skills are fundamental to many aspects of cognitive and psychosocial development, and that poor language skills are a barrier to educational success.

The current rollout of the NELI programme in English primary schools is a stunning example of how basic academic research can be translated into practical application at large scale

Developed by an Oxford team, led by Professors Charles Hulme and Maggie Snowling, the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI) programme improves oral language skills in young children. According to research by this group, there can be a transfer effect with oral language interventions, leading to improved reading comprehension.

As a result of official funding, it is hoped that all primary schools in England that want it, will benefit from the Oxford oral language programme. Last autumn, the Department for Education announced a £9 million investment in the programme, with a further £8 million announced for next academic year. In this academic year, this funding has enabled the programme to be delivered by some 6,500 schools. Schools wishing to register interest, can do so here.

The current rollout of the NELI programme in English primary schools is a stunning example of how basic academic research can be translated into practical application at large scale.

Children’s oral language skills are a critical foundation for the whole of formal education....Good language skills underlie a child’s ability to learn to read and to master arithmetic

Professor Charles Hulme

Professor Hulme says, ‘Children’s oral language skills are a critical foundation for the whole of formal education. To learn in the classroom, children need to understand what is said to them and be able to express their thoughts and feelings. Good language skills underlie a child’s ability to learn to read and to master arithmetic.’

Dr Gillian West, a member of the research team, comments, ‘Language skills are also critical for children’s social and emotional development, and their ability to make friends.’

Language skills can vary greatly among social groups. According to Professor Hulme, ‘It is well established that children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds often enter school with weak language skills. The NELI programme offers the potential to help reduce social inequalities in educational outcomes and can also be used effectively with children for whom English is an additional language.’

Language skills are also critical for children’s social and emotional development, and their ability to make friends

Dr Gillian West

The schools taking part identify five or six children in each reception class with the weakest oral language skills.

Last month, a study of NELI’s effects by Professor Hulme showed that the programme produced sizeable improvements in children’s language skills and small improvements in word reading skills.

Teachers and teaching assistants are trained to deliver the NELI programme using an online training programme, developed by the Oxford team, and delivered on the FutureLearn platform. The schools taking part identify five or six children in each reception class with the weakest oral language skills.

These children receive the programme get two 30 minute group sessions each week and three 20 minute individual sessions. During these periods, the children are involved in speaking and listening activities including storytelling and learning new words. Once staff are trained, NELI can be implemented in schools year after year, benefitting generations of children.

Identifying those children who would benefit from the programme is key. Teachers need a way to identify language weaknesses when using the NELI programme. A ‘LanguageScreen’ assessment app has been developed by Professor Hulme’s research group in collaboration with Dr Mihaela Duta and Dr Abhishek Dasgupta in Oxford’s Department of Computer Science. It is now available to all schools via an Oxford spinout company (LanguageScreen.com).

Dr Duta says, ‘It is a great pleasure to bring software engineering to bear on an issue of such social importance.’

Children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds often enter school with weak language skills. The NELI programme offers the potential to help reduce social inequalities in educational outcomes and can also be used effectively with children for whom English is an additional language

Professor Hulme

The Education Endowment Foundation, with private equity enterprise ICG, provided funding to develop online training for the programme, ensuring it could be offered in a social-distanced manner as well as at national scale.

LanguageScreen runs on a tablet or phone and gives teachers an accurate and rapid assessment of a child’s language ability via a secure automated online report. LanguageScreen will allow teachers to monitor the development of children’s language skills.

By Dr Ellie Bath, Department of Zoology

Mating changes female behaviour across a wide range of animals, with these changes induced by components of the male ejaculate, such as sperm and seminal fluid proteins. However, males can vary significantly in their ejaculates, due to factors such as age, mating history, or feeding status. This male variation may therefore lead to variation in the strength of responses males can stimulate in females.

Using the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, we tested whether age, mating history, and feeding status shape an important, but understudied, post-mating response – increased female-female aggression.

Two females fighting over food

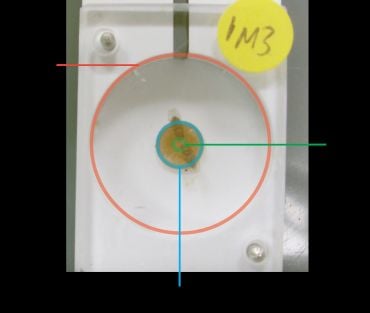

Two females fighting over foodImage 1: Two female fruit flies are standing on a food cap (which contains food that they eat and lay eggs in). This is where the majority of fighting happens – you can see the flies have their legs touching, so they are probably fencing in this image. Each fly is marked with a different colour of paint to aid identification.

We found that females mated to old males fought less than females mated to young males. Females mated to old, sexually active males fought even less than those mated to males who were merely old, but there was no effect of male starvation status on mating-induced female aggression.

Male condition can therefore influence how females interact with each other – who you mate with changes your interactions with members of the same sex!

Image 2: This figure shows the setup we used for contests between females, which consisted of a circular arena with a food cap set into the middle. This food cap contained regular fly food medium, with a drop of yeast paste in the middle to act as a valuable, restricted resource.

Contest arena setup

Contest arena setupCould this happen in other species?

We know that other species (including humans!) have proteins in the seminal fluid that males transfer to females during sex. Various of these proteins have effects on female physiology and behaviour, but no one knows if these affect aggression (in humans or any other species).

We also know that male age (in flies and humans) results in reduced fertility and can have serious effects on their offspring. Although it is a long leap from flies to humans, could who you mate with influence your interactions with other females?

Many reproductive molecules and important bodily functions are conserved across the animal kingdom from flies to humans, so it is possible that what we found in flies here might be hinting to a common phenomenon across the tree of life. We need more studies to understand if this is the case!

Read the full paper, 'Male condition influences female post mating aggression and feeding in Drosophila' in Functional Ecology.

By Professor Jane McKeating, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine

Oxygen is essential to all life forms, even viruses.

Oxygen is fundamental to all cells, impacting key functions such as metabolism and growth. Our cellular response to oxygen levels is tightly regulated and one important pathway is controlled by the Hypoxia Inducible Factors (HIFs), that activate certain genes under low oxygen conditions (hypoxia) to promote cell survival. Drugs that activate HIF are currently in use to treat anaemia caused by kidney disease.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 needs no introduction and literally stopped the world in 2020, with more than 2 million fatalities to date. A defining feature of severe COVID-19 disease is low oxygen levels throughout the body, which may lead to organ failure and death. A cure for this virus is urgently needed.

Dr Peter Wing and Dr Tom Keeley, working in the laboratories of Prof Jane McKeating, Prof Peter Ratcliffe and Dr Tammie Bishop in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, discovered that a low oxygen environment supressed SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells that line the lungs and reduced viral propagation and shedding.

Importantly, drugs that activate HIF such as Roxadustat had a similar effect on the virus. This study provides the first evidence for repurposing HIF mimetics that could reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission and disease development. The oxygen dependency of this virus is a new vulnerability that we could exploit.

Research continues to expand our understanding of the interplay between oxygen sensing and COVID-19 and is published in Cell Reports.

- ‹ previous

- 27 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria