Features

Dr Tessa Roynon

The US Capitol in Washington DC has been much in the public eye in recent weeks. Whether stormed by President Trump supporters on 6 January, or as the ‘hallowed ground’ that formed the backdrop to President Biden’s inauguration two weeks later, the gleaming perfection of its neoclassical architecture is an unquestioned part of its iconic status.

By contrast, in The Classical Tradition in Modern American Fiction, I take a more quizzical and, at times, sceptical approach to the American love affair with ancient Greece and Rome - and a long, hard look at American novelists’ predilection for classical allusion.

It asks what is at stake when seven key fiction writers of the 20th/21st centuries: Willa Cather, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, and Marilynne Robinson, refer to the work of Aeschylus, or Homer, or Virgil, or Ovid, in their explorations of modern identity and experience.

It asks what is at stake when seven key fiction writers of the 20th/21st centuries: Willa Cather, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, and Marilynne Robinson, refer to the work of Aeschylus, or Homer, or Virgil, or Ovid, in their explorations of modern identity and experience.

We tend to be far too reverential when faced with allusions to Greek and Roman literature...We tend to assume that such references bestow an immediate and universal authority...We are unthinkingly impressed

The project grew out of my perception, as a reader and a teacher, that we tend to be far too reverential when faced with allusions to Greek and Roman literature, myth, history or visual art. We tend to assume that such references bestow an immediate and universal authority on a text. We are unthinkingly impressed.

My own conviction is that we need to pay close attention when modern writers invoke the ancient past, because they often reach for distant heroes and stories in order to discuss some of the most pressing ideological issues of their (and our) times.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, for example, is obsessed in his fiction with a decadent and ultimately fallen ancient Rome, and he uses this motif to bolster a nativist and anti-immigrant conception of Americanness.

Willa Cather, in Sapphira and the Slave Girl, added many of her classical allusions and framing devices in a very late re-drafting stage - almost as an afterthought, she distorts the realities of slavery and racial injustice through deploying ‘Old Southern’ nostalgic and heroic tradition.

And Philip Roth disguises a visceral misogyny as ‘masculinity’, in his much-feted novel The Human Stain, through the repeated association between his protagonist, Coleman Silk, and Zeus. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which Roth frequently invokes, Zeus is a voracious rapist, but Roth attempts to use him to shore up the sense of Coleman as virile hero.

Why do we tend to be such un-alert or acquiescent readers when it comes to antiquity?...we do not study Latin, Greek, or classical civilization at school

Why do we tend to be such un-alert or acquiescent readers when it comes to antiquity? One reason is that nearly all of us are hazy on the details, because we do not study Latin, Greek, or classical civilization at school. A working knowledge of the classical tradition appears now, for the most part, the preserve of an elite minority. If we are not exactly sure who Trimalchio, Hector or Leda is, when these canonical American writers call them up, we are most likely to nod our heads nervously and move quickly on.

The Classical Tradition in Modern American Fiction sets out to counter this process by insisting that the classical past is accessible to all. Complete with its own glossary of every classical name and concept discussed, as well as a guide to the best among the numerous online-resources, it is underpinned by my sincere conviction that all we need to do, when faced with an unfamiliar Greek or Roman term, is the blindingly-obvious: ‘look it up’.

My conviction is deeply-held for two reasons. First, in teaching these authors to my students over the years, I realised nearly all of them felt excluded from the entirety of classical culture. They needed encouragement to look things up but their confidence grew when they did. Second, I was inspired by my research into these each of these writers’ intellectual formation.

All we need to do, when faced with an unfamiliar Greek or Roman term, is the blindingly-obvious: ‘look it up’

In order to understand how they encountered the ancient world, I consulted archives and prior scholarship to understand how and where each studied, how they accessed the classical tradition, what they had read and what they thought about the reading that they had done.

Their contrasting backgrounds and experiences are striking. In the 1890s, Willa Cather studied Latin and Greek to a high level at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. Philip Roth was highly-educated, including undertaking graduate studies at Chicago, but he never studied the classical languages. Marilynne Robinson has a PhD in English, but studied Latin at high school. Toni Morrison was a Classics minor at Howard. Meanwhile, neither Fitzgerald, Faulkner nor Ellison even completed their undergraduate degrees.

The time period which my chosen authors span, Cather was born in 1873, and Robinson (the only one still living) was born in 1943, encompasses a series of different eras in which classical traditions were variously significant: fin-de-siecle decadence, modernism, liberal humanism, the Great Books tradition and the culture wars of the 1980s. Yet, despite these novelists’ widely diverging contexts, and their widely diverging levels of formal education, they have in common an unqualified passion for reading, and a voracious auto-didacticism.

For me, encountering first-hand the annotations Ralph Ellison made, very often about African American life - in the margins of his translations of Aeschylus, was an unforgettable thrill. Ellison, born in 1913 in Oklahoma City, was so impoverished when he began his undergraduate degree at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama that he rode ‘hobo’ on trains through the 1930s’ Deep South, to get there. His commitment to his own education, the extraordinary number of books he read, in numerous fields and his stalwart belief in the significance of the classical tradition to his own and to black American life, is a humbling and inspiring example I shall never forget.

Dr Roynon is a Senior Research Fellow at Oxford's Rothermere American Institute.

The RAI is hosting a webinar book launch on 11 February to which all are welcome.

Register in advance at this link: https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_1wCpXBqbRa-w7NkDdwSgvA

The evolutionary biologist Olivia Judson wrote, ‘The battle of the sexes is an eternal war.’

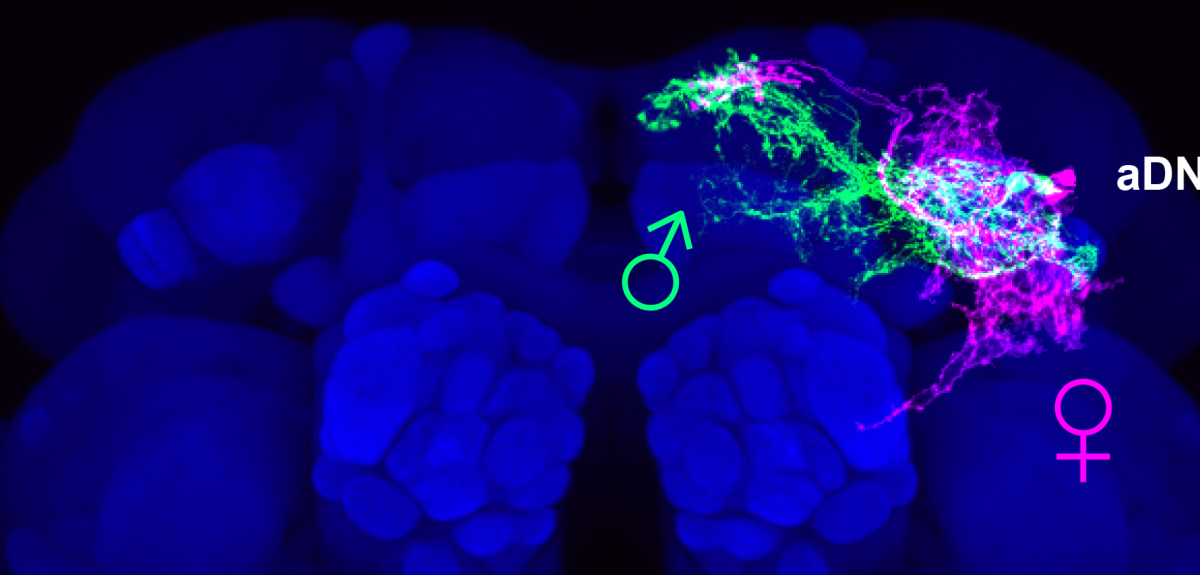

Males and females not only behave differently in terms of sex, they are evolutionarily programmed to do so, according to a new study from Oxford, which found sex-specific signals affect behaviour.

Males and females not only behave differently in terms of sex, they are evolutionarily programmed to do so

The new study from Oxford’s Goodwin group from the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics says, despite sharing very similar genome and nervous system, males and females ‘differ profoundly in reproductive investments and require distinct behavioural, morphological, and physiological adaptations’.

The team argues, ‘In most animal species, the costs associated with reproduction differ between the sexes: females often benefit most from producing high-quality offspring, while males often benefit from mating with as many females as possible. As a result, males and females have evolved profoundly different adaptations to suit their own reproductive needs.’

Males and females have evolved profoundly different adaptations to suit their own reproductive needs

The question for the researchers was: how does selection act on the nervous system to produce adaptive sex-differences in behaviour within the bounds set by physical constraints, including both size and energy, and a largely shared genome?

Today’s study offers a solution to this long-standing question by uncovering a novel circuit architecture principle which allows deployment of completely different behavioural repertoires in males and females, with minimal circuit changes.

The research team, led by Dr Tetsuya Nojima and Dr Annika Rings, found that the nervous system of vinegar flies, Drosophila melanogaster, produced differences in behaviour by delivering different information to the sexes.

In the vinegar fly, males compete for a mate through courtship displays; thus, the ability to chase other flies is adaptive to males, but of little use to females. A female’s investment is focused on the success of their offspring; thus, the ability to choose the best sites to lay eggs is adaptive to females.

When investigating the different role of only four neurons clustered in pairs in each hemisphere of the central brain of both male and female flies, the researchers found the sex differences in their neuronal connectivity reconfigures circuit logic in a sex-specific manner. In essence, males received visual inputs and females received primarily olfactory (odour) inputs. Importantly, the team demonstrated that this dimorphism leads to sex-specific behavioural roles for these neurons: visually guided courtship pursuit in males and communal egg-laying in females.

In essence, males received visual inputs and females received primarily olfactory (odour) inputs

These small changes in connectivity between the sexes allowed for the performance of sex-specific adaptive behaviour most suited to these reproductive needs through minimal modifications of shared neuronal networks. This circuit principle may increase the evolvability of brain circuitry, as sexual circuits become less constrained by different optima in male and females.

And it works, the study says, ‘Ultimately, these circuit reconfigurations lead to the same end result—an increase in reproductive success.

'Our findings suggest a flexible strategy used to structure the nervous system, where relatively minor modifications in neuronal networks allow each sex to react to their surroundings in a sex-appropriate manner.'

Furthermore, this is the first time a firm link between sex-specific differences in neuronal networks have been explicitly linked to behaviour.

According to Professor Stephen Goodwin, 'Previous high-profile papers in the field have suggested that sex-specific differences in higher-order processing of sensory information could lead to sex-specific behaviours; however, those experiments remained exclusively at the level of differences in neuroanatomy and physiology without any demonstrable link to behaviour. I think we have gone further as we have linked higher-order sexually dimorphic anatomical inputs, with sex-specific physiology and sex-specific behavioural roles.'

We have linked higher-order sexually dimorphic anatomical inputs, with sex-specific physiology and sex-specific behavioural roles

Professor Stephen Goodwin

The researchers maintain ‘evolutionary forces’ have driven these adaptations, ‘Drosophila, males compete for a mate through courtship displays, while a female’s investment is focused on the success of their offspring.’

They conclude, ‘In this study, we have shown how a sex-specific switch between visual and olfactory inputs underlies adaptive sex differences in behaviour and provides insight on how similar mechanisms maybe implemented in the brains of other sexually-dimorphic species.’

The full paper, A sex-specific switch between visual and olfactory inputs underlies adaptive sex differences in behaviour, joint-first authored by Dr Tetsuya Nojima and Dr Annika Rings, is available to read in Current Biology.

Twenty three thousand years ago, canines travelled to the New World with the First Americans

When President Biden took up residence last week in the White House, Major and Champ became the latest dogs in a long history, to follow their people on an American journey. Research published this week reveals that the relationship between not just the first Americans’ but everyone’s best friend was deeper than previously thought – 23,000 years’ deep, in fact.

According to the new research, from an international team of archaeologists and geneticists including Oxford’s Professor Greger Larson, dogs travelled alongside the first people who made the journey across the Bering straits to the Americas.

The research reveals dogs spread throughout the Americas, along with people, and developed completely separately to their European cousins

The research reveals dogs then spread throughout the Americas, along with people, and developed completely separately to their European cousins. When the first European settlers arrived across the Atlantic, bringing their dogs of course, the indigenous American dogs were genetically distinct. And, as with many indigenous peoples – the indigenous American dogs all-but died out, when confronted with European people and dogs.

Today, there is little trace left of the animals who braved the long journey during the last Ice Age, to accompany their fellow human travellers into a new land.

As with many indigenous peoples – the indigenous American dogs all-but died out, when confronted with European people and dogs

According to the study, ‘The first people to enter the Americas likely did so with their dogs. The subsequent geographic dispersal and genetic divergences within each population suggest that where people went, dogs went too.’

Professor Larson says, ‘We found a very strong correlation between the pattern of ancient dogs’ genetic diversification and the genetic signatures of early Americans. The similarities between the two species is striking and suggests the shared pattern is not a coincidence.’

He adds, ‘We knew dogs were the oldest domesticated species, and these findings now suggest that the initial process of domestication began around 23,000 years ago in north-east Siberia. From there, people and dogs moved together east into the Americas, south towards east Asia, and west towards Europe and Africa.'

We knew dogs were the oldest domesticated species, and these findings now suggest that the initial process of domestication began around 23,000 years ago in north-east Siberia

Professor Greger Larson

According to this week’s report, ‘The convergence of the early genetic histories of people and dogs in Siberia and Beringia suggests that this may be the region where humans and wolves first entered into a domestic relationship...this process likely began between 26,000 and 19,000 years ago, which precedes evidence for the first unequivocal dogs in the archaeological record by as much as 11,000.’

This is important research, not only for what it says about dogs’ arrival in the Americas, but also for what it reveals about people. And the report states, ‘Since their emergence from wolves, dogs have played a wide variety of roles within human societies, many of which are specifically tied to the lifeways of cultures worldwide. Future archaeological research combined with numerous scientific techniques, will no doubt reveal how the emerging mutual relationship between people and dogs led to their successful dispersal across the globe.’

This is not the first time Professor Larson has produced research about ancient dogs (and Dire Wolves). Does this new study reveal a preference for canines?

Imagine what society would be like if we had not formed mutually interdependent relationships with so many other domestic plants and animals. And it all started with dogs

Professor Larson

‘I grew up with dogs, and I always interact with them when they walk by’ he says. ‘Dogs were the first species to enter into a mutualistic relationship with us. It was a key shift in the evolution of our species...It is amazing how much everything began to change after that.

'For the vast majority of our species’ history we travelled alone and made a tiny impression on the earth’s ecology. Now there are eight billion of us and we depend on a range of domestic plants and animals for the maintenance of our huge global population. Imagine what society would be like if we had not formed mutually interdependent relationships with so many other domestic plants and animals. And it all started with dogs.’

The article in PNAS is available here: https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2010083118

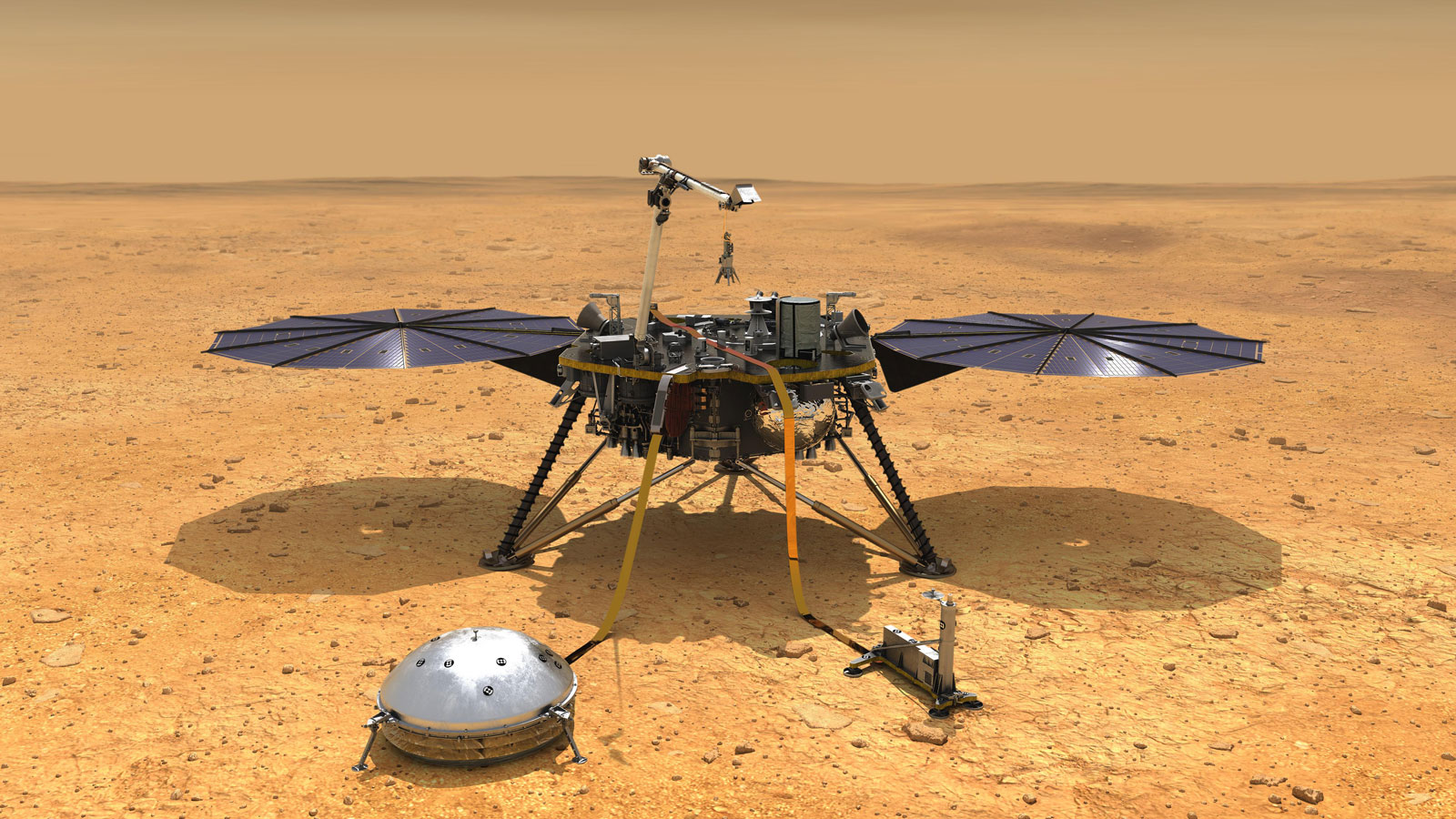

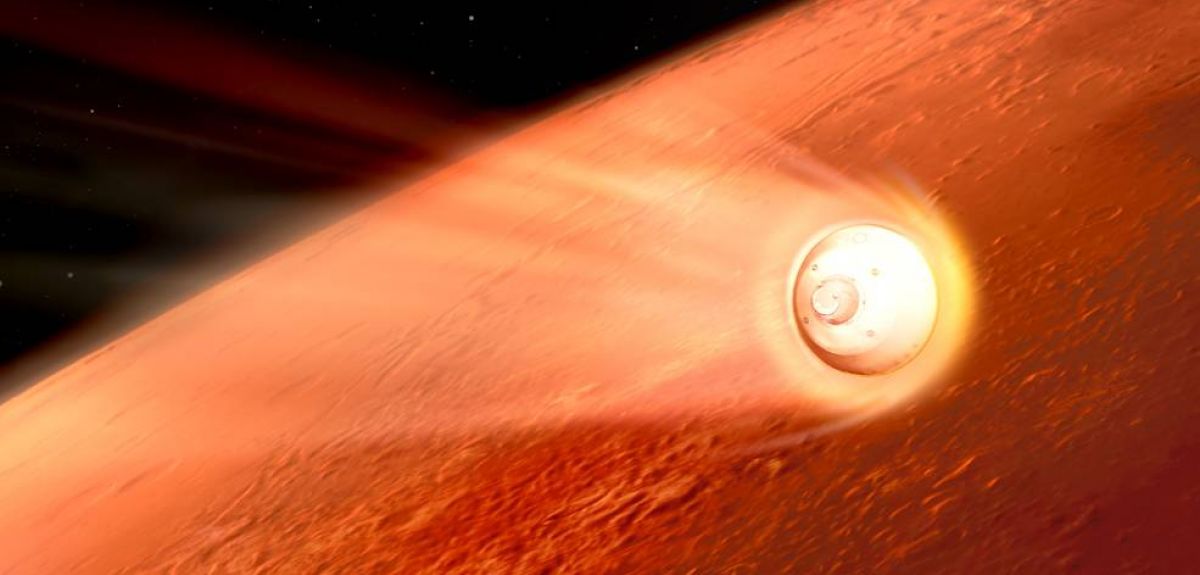

We may not have found life on Mars, but there is considerable excitement in the Oxford scientific community about the imminent possibility of detecting the landing of NASA’s Perseverance Rover using InSight, another spacecraft which is already on the red planet.

University physicists believe that, for the first time, they might be able to ‘hear’ a spacecraft land on Mars, when Perseverance arrives at Earth’s ‘near’ neighbour in about a month’s time around 18 February.

And NASA’s new probe is certainly not arriving quietly. The unmanned craft will plunge through the Martian atmosphere at enormous speeds, accompanied by a sonic boom created by its rapid deceleration. At the point it enters the atmosphere, it will be travelling at more than 15,000 km/h and its heat shield will reach more than 1,300 degrees centigrade during the descent.

NASA’s new probe is certainly not arriving quietly. The unmanned craft will plunge through the Martian atmosphere at enormous speeds, accompanied by a sonic boom created by its rapid deceleration

It will deploy two large balance masses which will hit the ground at hypersonic speeds, crashing down at a speed of 4,000 metres per second. It is these two masses which the scientists are hoping will create detectable seismic waves - which will travel the 3,452 kilometres between Perseverance’s landing site and InSight’s location.

The ears to ‘hear’ the impact are the InSight probe, which was sent to Mars three years ago to listen for seismic activity and impacts from meteorites. Parts of the spacecraft were built at Imperial College London and tested in the Department of Physics at the University of Oxford.

InSight detects seismic activity (marsquakes) to help scientists understand better the interior structure of Mars. Although many hundreds of marsquakes have been detected since InSight’s landing in 2018, no impact events (meteorites hitting the surface and producing seismic waves) have been detected. Impact events are of particular interest because they can be constrained in timing and location from pictures taken by orbiting satellites, and thus used to ‘calibrate’ seismic measurements.

So, the arrival of Perseverance Rover potentially offers the first opportunity to detect a known, planned landing of a foreign body on the surface of the planet. It could provide a wealth of evidence on the structure and atmosphere of Mars and has got the scientific community very excited about its potential.

According to Oxford physicist, Ben Fernando, a member of the InSight team, ‘This is an incredibly exciting experiment. This is the first time that this has ever been tried on another planet, so we’re very much looking forward to seeing how it turns out.’

This is the first time that this has ever been tried on another planet, so we’re very much looking forward to seeing how it turns out

InSight team member, Ben Fernando

InSight’s seismometers are potentially sensitive enough to detect Perseverance’s landing, even though this is expected to be very challenging - given the significant distance between the two landing sites. It is around the same distance as from London to Cairo. Nevertheless, the Oxford team believes the impact could potentially be detected by InSight and thus provide an immensely useful ‘calibration’.

According to Ben Fernando, ‘This would be the first event detected on Mars by InSight with a known temporal and spatial localisation. If we do detect it, it will enable us exactly to constrain the speed at which seismic waves propagate between Perseverance and InSight.’

A newly-published paper from the InSight team states, ‘Perseverance’s landing is targeted for approximately 15:00 Local True Solar Time (LTST) on February 18, 2021 (this is 20:00 UTC/GMT on Earth).’

The paper continues, ‘The spacecraft will generate a sonic boom during descent, from the time at which the atmosphere is dense enough for substantial compression to occur (altitudes around 100 km and below), until the spacecraft’s speed becomes sub-sonic, just under three minutes prior to touchdown. This sonic boom will rapidly decay into a linear acoustic wave, with some of its energy striking the surface and undergoing seismo-acoustic conversion into elasto-dynamic seismic waves, whilst some energy remains in the atmosphere and propagates as infrasonic pressure waves.’

The paper concludes, ‘We identified three possible sources of seismo-acoustic signals generated by the EDL (entry, descent, landing) sequence of the Perseverance lander: (1 ) the propagation of acoustic waves in the atmosphere formed by the decay of the Mach shock, (2) the seismo-acoustic air-to-ground coupling of these waves inducing signals in the solid ground, and the elasto-dynamic seismic waves propagating in the ground from the hypersonic impact of the CMBDs.’

InSight will ‘listen’ for the acoustic signal of the sonic boom in the atmosphere. But scientists think the best chance of detecting the landing will be the seismic impact of the balance masses.

The team expects to receive data from InSight within a day or two of Perseverance’s landing, after which they will investigate whether they have made a successful detection.

Short explanatory video: http://bit.ly/insight-m2020-video

Instagram film: https://www.instagram.com/tv/CJvxmSaokd3/

COVID-19 has asked a lot of everyone. At the national level, decisions have been taken that affect everything from people’s movements to the running of businesses. For many, there are also individual decisions in which personal risks are weighed: Should I venture to my local grocery store, or should I shop online? Can I eat at the restaurant, or should I buy take out?

In many households, dinner time musings often drifted to something like the following: 'I have barely seen anyone in person for many weeks. I know my neighbours haven’t either. My favourite park is much emptier than usual and the community around me has made many sacrifices. Does this mean COVID-19 is actually decreasing in my area?'

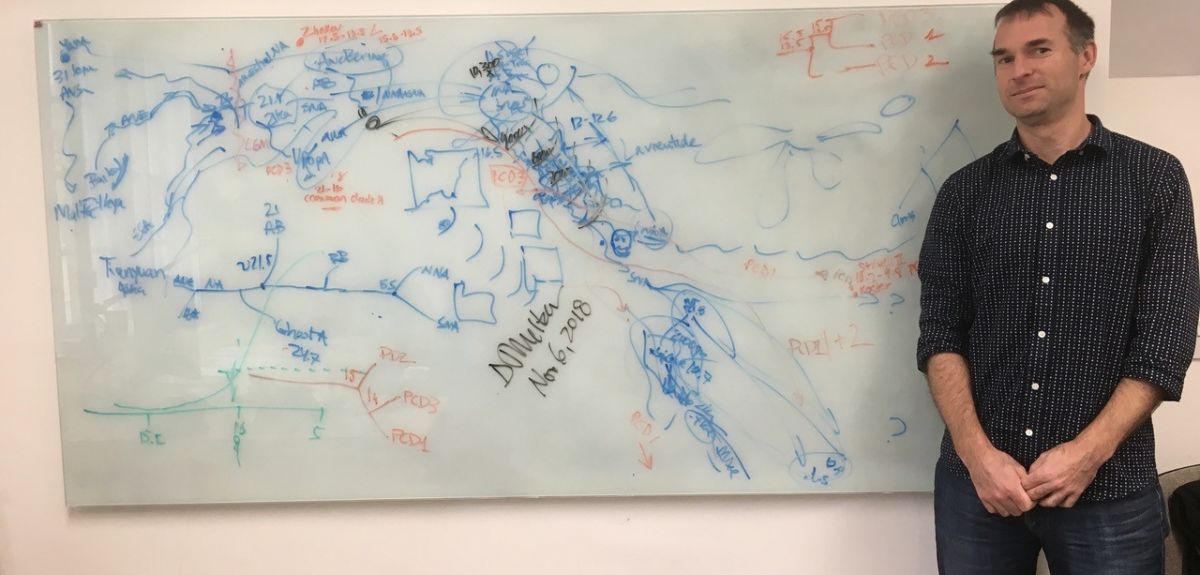

While most people have a UK-wide view and newspapers report national statistics, the decisions that people make to help contain the pandemic are at an individual and personal level. The behaviour of people in Oxford has no sizable effect on COVID-19’s growth or decline in far away Scotland, and these decisions need real-time, local information, an up to date resource that anyone can access to see how their town or county is doing.

View Local Covid UK Map here: https://localcovid.info/

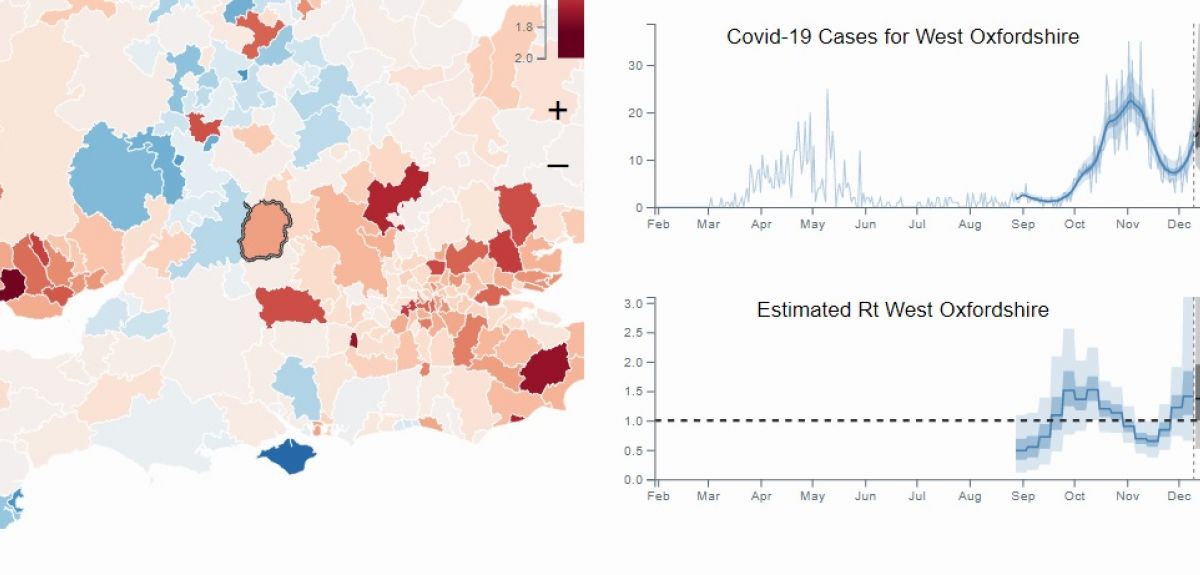

Using historical COVID-19 case counts, the map at localcovid.info shows an estimate for the R number in each local area, along with projections of how the epidemic might develop in the next two weeks

The reproduction number or “R number” tells us about the growth and decline of COVID-19. It is an estimate of the number of people that someone with COVID-19 will pass the virus on to. A reproduction number of R=2 means that an infected person is likely to transmit the virus on to two other people, each of whom then passes it to two more people, and the epidemic grows quickly. On the other hand, if R=1, then on average each infected person only infects one other person and the size of the epidemic remains roughly constant. A reproduction number of R<1 is good news: the number of new infections is reducing and over time the epidemic will shrink.

Yee Whye Teh, Professor of Statistical Machine Learning at the Department of Statistics, University of Oxford, explains how the national “R number” is made up of many local parts: 'The national R number describes an average transmission rate across the nation. It is an aggregate statistic made up of many smaller contributions, and belies significant variations in COVID-19 transmissions rates, both geographically as well as across different sections of society. In order to inform individual decisions, local information relevant to the individual is needed.'

Led by Professor Teh, a team from the Computational Statistics and Machine Learning research group at Oxford’s Department of Statistics has built a model that monitors the daily spread of the virus locally. Their results can be accessed online by anyone at localcovid.info, which gives an informative view of the rate of transmission of COVID-19 in areas such as Oxford, Cherwell, West Oxfordshire, Swindon and more than 300 other local authorities in the UK.

Using historical COVID-19 case counts, the map at localcovid.info shows an estimate for the R number in each local area, along with projections of how the epidemic might develop in the next two weeks. The estimates of R in the map contain what statisticians call “error bars” or “credible intervals”. These are there to say that no one knows the true R number in an area, but we are quite sure that we can pin it down to within a narrow band. For example, in the map snapshot December 14, we are 95% sure that R is currently between 0.7 and 1.4 in Oxford, with a median of 1.0, given the team’s statistical model and the data available.

The real work dynamics of epidemics are incredibly complicated.

Michael Hutchinson, a PhD student in professor Teh’s group, explains how the “R number” is estimated from data: 'This is a difficult task. The real work dynamics of epidemics are incredibly complicated. To begin estimating the R number we start by proposing a simplified statistical model of the real world which captures the most important aspects of the epidemic. We never observe the R number directly, we only observe positive COVID-19 cases. We know that the R number drives new infections however, so using the model and observations of numbers of cases we can infer what R is likely to be. Essentially, using what we see in the world, we reverse engineer what the unobservable R is.'

The statistical model underlying these estimates of R relies on publicly available Pillar 1+2 daily counts of positive PCR swab tests by specimen date, for 312 lower-tier local authorities in England, the 14 NHS Health Boards in Scotland and the 22 unitary local authorities in Wales. The model makes additional use of commuter flow data from the UK 2011 Census and population estimates, as COVID-19 spreads not just among the population of individual areas, but also across areas. As with many aspects of statistical epidemiology, these estimates of R need to be read with care, and in the context of other pieces of data that provide relevant information, e.g. data from the ZOE symptom tracker, seroprevalence studies, test positivity rates, as well as hospitalisation and death rates.

Dr. Ulrich Paquet, a research scientist seconded to the group, noted: 'We are pleasantly surprised to see how the estimates for R have dropped below one for a while in many areas, especially in the North where Tier 3 rules applied since October. We guess that we shouldn’t be surprised to see the result of public behaviour and national action show up so clearly in a model, but we still are! As statisticians, we love it when the data speaks for itself.'

Prof. Teh concluded on a more sombre note: 'We are concerned that since the lockdown was lifted in December, many areas, particularly in the Southeast and London, have seen cases continue to increase. We hope the tool we built at localcovid.info will be helpful to you, in making your decisions to stay safe and to help protect your loved ones.'

Track your local area on the Local Covid UK Map here: https://localcovid.info/.

- ‹ previous

- 31 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria