Features

Oxford academics are teaming up with Google DeepMind to make artificial intelligence safer.

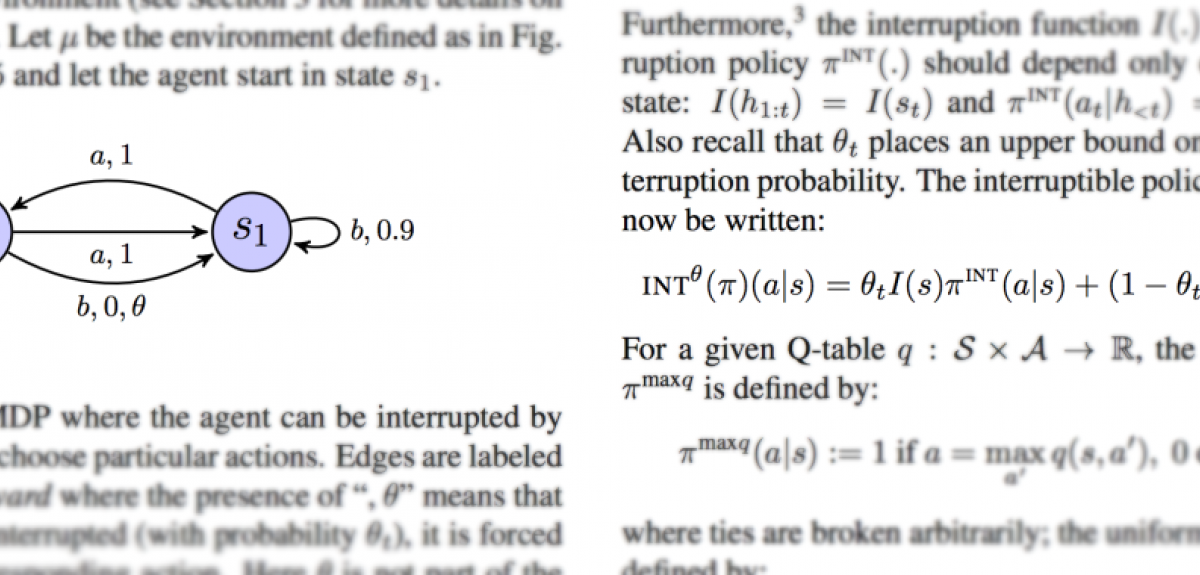

Laurent Orseau, of Google DeepMind, and Stuart Armstrong, the Alexander Tamas Fellow in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning at the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, will be presenting their research on reinforcement learning agent interruptibility at the Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence conference in New York City later this month.

Orseau and Armstrong's research explores a method to ensure that reinforcement learning agents can be repeatedly safely interrupted by human or automatic overseers. This ensures that the agents do not “learn” about these interruptions, and do not take steps to avoid or manipulate the interruptions.

The researchers say: 'Safe interruptibility can be useful to take control of a robot that is misbehaving… take it out of a delicate situation, or even to temporarily use it to achieve a task it did not learn to perform.'

Laurent Orseau of Google DeepMind says: 'This collaboration is one of the first steps toward AI Safety research, and there's no doubt FHI and Google DeepMind will work again together to make AI safer.'

A more detailed story can be found on the FHI website and the full paper can be downloaded here.

This is a guest post by Mary Cruse, science writer at Diamond Light Source.

All over the world, engineers are beset by a niggling problem: when materials get hot, they expand.

Why is this such an issue? Well, because materials get hot all the time. Think about aeroplanes, buildings, bridges or virtually any kind of technology.

When you expose any of these materials to energy – whether that energy comes from the sun, fuel burning in an engine or from an electric current – they're going to get bigger, and in some cases that can cause them to fail.

Whether it's a case of seasonal cracks in the road surface or a short-circuited smart phone, thermal expansion can be the bane of an engineer's existence.

But thanks to Oxford University scientists, heat-related failure could ultimately become a thing of the past.

Not all materials expand when they get hot. These so-called 'negative thermal expansion' - or NTE – materials actually contract when heated.

But scientists have never been able to control this process. The material might shrink too far or not far enough. Without being able to modulate this contraction, we just can't harness the potential of NTE materials.

However, research announced this week could change all that. A group led by Dr Mark Senn of Oxford's Department of Chemistry has successfully developed a way of manipulating a class of materials into expanding or contracting at will.

The international collaboration, made up of scientists from Oxford, Imperial, Diamond Light Source and institutions in Korea and the US, haa hit upon a potentially revolutionary finding.

NTE is caused by atoms vibrating inside a material – these vibrations cause the atoms to move closer together. In the past, we haven't been able to control how much closer the atoms became or how quickly the process takes place.

But the work of Dr Senn and his group has revealed that it's possible to manipulate this effect in a perovskite material by changing the concentration of two key elements: strontium and calcium.

The group found that changing these two elements proved to be the key to harnessing the power of NTE in the perovskite they were studying. And if we can control that expansion and contraction, then we have a powerful new resource for engineering technology and infrastructure.

This is an early step forwards, but the findings of the Senn group have opened the door for other researchers looking to control NTE materials. We know that adjusting the elemental composition of this perovskite works: it may be that the same method could work for other materials.

Dr Senn explained the impact of the work: 'This is hugely exciting because we now have a "chemical recipe" for controlling the expansion and contraction of the material when heated. This should prove to have much wider applications.'

Dr Claire Murray is a support scientist at Diamond Light Source. Her expertise in synchrotron science allowed the group to scrutinise the very small changes on the atomic length scale occurring in the perovskite as its composition changed.

She said: 'Researchers are increasingly turning to synchrotrons like Diamond to deepen their understanding of chemical processes and, in a similar way to chefs adjusting their recipes to get a better texture or taste, scientists are adjusting the elemental composition of materials, and thereby controlling their properties and functions in ways that will bring performance and safety benefits in a wide range of areas including transport, construction and new technology.'

There may be some way to go before we start seeing NTE materials in our phones and aeroplanes, but we now know how to control this material, and that's a major step forward.

The laws of physics may sometimes be stacked against engineers, forcing them to design products that account for uncontrollable expansions and contractions, but research like this gives us just that little bit more control.

And when it comes to engineering our everyday lives – from transport to technology – that can make all the difference.

This blog post is adapted from an article published by the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research.

Plants use many strategies to disperse their seeds, but among the most fascinating are exploding seed pods. Scientists had assumed that the energy to power these explosions was generated through the seed pods deforming as they dried out, but in the case of 'popping cress' (Cardamine hirsuta – a common garden weed) this turns out not to be the case. A new paper by an international group of researchers, published in the journal Cell, offers new insights into the biology and mechanics behind this process.

Several teams of scientists spanning different disciplines and countries, including Oxford mathematicians Alain Goriely and Derek Moulton, along with colleagues from Oxford's departments of Plant Sciences, Zoology and Engineering, worked together to discover how the seed pods of popping cress explode. A rapid movement like this is rare among plants: since plants do not have muscles, most movements in the plant kingdom are extremely slow. However, the explosive shatter of popping cress pods is so fast – an acceleration from 0 to 10 metres per second in about half a millisecond – that advanced high-speed cameras are required to see it.

The scientists, led by Angela Hay, a plant geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research, discovered that the secret to explosive acceleration in popping cress is the evolutionary innovation of a fruit wall that can store elastic energy through growth and expansion and can rapidly release this energy at the right stage of development.

Previously, scientists had claimed that tension was generated by differential contraction of the inner and outer layers of the seed pod as it dried. So what puzzled the authors of the Cell paper was how popping cress pods explode while green and hydrated, rather than brown and dry. Their surprising discovery was that hydrated cells in the outer layer of the seed pod actually use their internal pressure in order to contract and generate tension.

The authors used a computational model of three-dimensional plant cells to show that when these cells are pressurized, they expand in depth while contracting in length – much like an air mattress does when inflated.

Another unexpected finding was an evolutionary novelty explaining how this energy is released. The authors found that the fruit wall seeks to coil along its length to release tension but is prevented from doing so by its curved cross-section. Professor Moulton said: 'This geometric constraint is also found in a toy called a slap bracelet. In both the toy and the seed pod, the cross-section first has to flatten before the tension is suddenly released by coiling.' Unexpectedly, this mechanism relies on a unique cell wall geometry in the seed pod. Professor Moulton added: 'This wall is shaped like a hinge, which can open, causing the fruit wall to flatten in cross-section and explosively coil.'

Emphasising the multidisciplinary, collaborative approach to this paper, Professor Goriely said: 'This approach was only made possible by combining state-of-the-art modelling techniques with biophysical measurements and biological experiments.'

Most of us will be at least vaguely aware that our planet's coral reefs are in jeopardy. But why are they in danger, and what can we do about these threats?

A new report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has set out to provide a health check for a particular type of underwater ecosystem known as mesophotic coral reefs. Mesophotic reefs are found deeper in tropical and subtropical waters than the shallower reefs we may be more familiar with. And, according to the report, these ecosystems may be able to act as 'lifeboats' for threatened species living in shallower reefs.

Two DPhil students in Oxford's Department of Zoology, Jack Laverick and Dominic Andradi-Brown, co-authored a chapter of the report examining the threats facing mesophotic reefs. They spoke to Science Blog about the diving expeditions that allowed them to identify the dangers posed to these fragile ecosystems – large, underwater structures composed of the hard, calcium carbonate 'skeletons' of coral, a marine invertebrate.

Dominic, who also sat on the steering group for the report, explained: 'Our research on mesophotic coral ecosystems took us to Honduras and Indonesia. At first glance the mesophotic reefs look similar to shallow reefs – we see many similar species and groups, including corals, sponges and algae. However, when you look a little more closely you see that many of these species and groups have taken on slightly different forms. For example, corals tend to be flatter, while sea fans tend to be larger.

'During the course of our research we spotted many species of fish at depth that are threatened in shallower waters. In September 2015 in Honduras we observed Caribbean reef sharks at depths of 60m, whereas these sharks are near-absent from shallow reefs because of historically high levels of shark fishing.'

Jack said: 'Mesophotic coral ecosystems are quite different to the shallow reefs many people are aware of. We say these reefs are found in the "twilight zone", as light fades exponentially with increasing depth. Amazingly, despite it being barely light enough for us to see when we visit the deepest extents of these coral reefs, hard corals are still able to photosynthesise.

'To get around the lack of light energy, hard corals become increasingly flat and fragile, capturing the most light energy possible for the smallest amount of growth. These discs can stack in a shingle-like pattern, casting a very different scene to what is commonly seen near the surface.

'Our work is scheduled extremely tightly when we visit these ecosystems, leaving little time to enjoy being on the reefs. Despite this, working in the twilight zone has us convinced that mesophotic coral ecosystems require their own protection – as a potential store of shallow reef species, for the services they provide, and for their own haunting beauty.'

In his foreword to the report, outgoing UNEP Executive Director Achim Steiner (who will be taking up a post at Oxford University's Oxford Martin School) points out that almost a fifth of coral reefs have disappeared thanks to human activity, with a further 35% expected to be lost in the next 40 years – unless we act now.

He adds: 'Coral reefs provide both tangible and intangible benefits to the lives of millions of people. From providing food and income to protecting our coasts from damaging storms, coral reefs make an incalculable contribution to coastal communities, as well as to the organisms that depend on them.'

But while mesophotic coral reefs may provide a lifeline for some of the shallow-reef organisms threatened by human activity, they also face threats of their own.

Dominic explained: 'One example of a major threat that we're studying here in Oxford is invasive lionfish in the Caribbean. Lionfish were introduced to the Caribbean from the Indian and Pacific Oceans and have rapidly spread across the region. During our research we've observed them deeper than 100m, where they feed on native reef fish, causing knock-on effects throughout mesophotic ecosystems.

'Current control measures are focused on culling, with divers removing individual lionfish from the reef. However, this is normally limited to depths shallower than 30m, which is the normal limit for scuba divers. Our work highlights the importance of considering the role of deeper reefs in management plans for lionfish control.'

Both Jack and Dominic emphasise the importance of the report – and of acting on it.

Jack said: 'This report is a major step forward in highlighting the existence of these deep reefs, which many people have never heard about. As we find ourselves in the midst of the third global coral-bleaching event – when warmer water temperatures result in coral losing their algae – it is important that people are made aware that these extensive reefs exist; reefs that could help stave off a global disaster by storing species for future regeneration of shallow ecosystems. We might have a lifeline for coral reefs globally, and we must not waste this resource.'

Dominic added: 'Mesophotic reefs are little explored, yet this report highlights that they may have a crucial role to play in helping maintain healthy coral reefs in the face of current and future reef threats. But despite the added protection they have from being deeper, this doesn't mean they are immune to damage.'

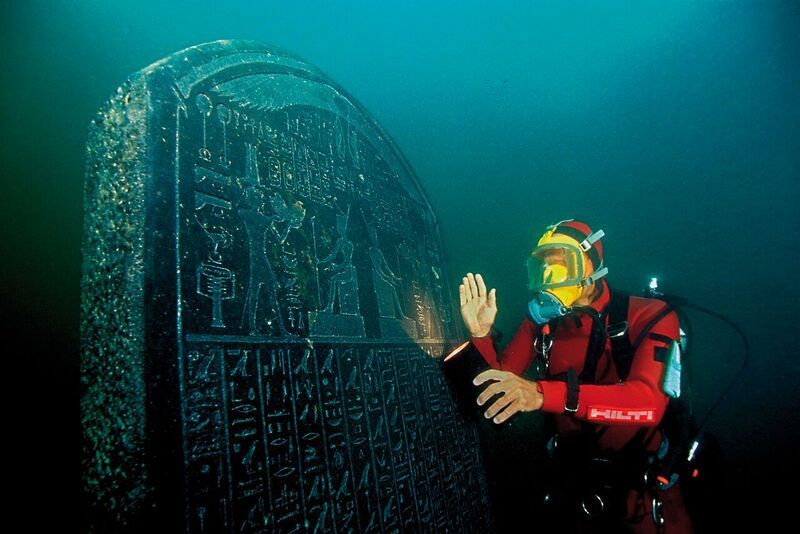

These spectacular images show divers recovering treasures from two ancient Egyptian cities.

The artefacts from Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus had been submerged at the mouth of the River Nile for over a thousand years.

Researchers from the University of Oxford's Centre for Maritime Archaeology (OCMA) and senior staff from the School of Archaeology and Faculty of Classics have conducted much of the detailed scholarly and scientific research that underpins interpretations of life in the cities.

The OCMA supports Franck Goddio and his team, the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology, which is responsible for excavating spectacular finds off the coast of Egypt near Alexandria and their interpretation.

Dr Robinson said: 'The significance and scale of the material from these sites is enormous and the condition of the objects is largely pristine. Monumental statues, fine metal-ware and gold jewellery reveal how Greece and Egypt traded and generally interacted in the late first millennium BC.

'Because ritual objects and refuse were placed into the waters of the harbour, they have been protected from the typical patterns of recycling and reuse that operate on land. Only now are we able to see the catastrophic destruction of areas of the site that largely led to its abandonment.'

The objects were found at the mouth of the River Nile

The objects were found at the mouth of the River NileRecovered statuettes and votive objects, metalware, and jewellery show the city was also a major religious centre where cross-cultural exchange and religion flourished, particularly the worship of the Egyptian god of the afterlife, Osiris.

The archaeological discoveries are the subject of a new six-month exhibition, ‘The BP exhibition – Sunken cities: Egypt’s lost worlds’, which opened this month at the British Museum in London.

Just one of the striking objects recovered from the dive

Just one of the striking objects recovered from the dive- ‹ previous

- 125 of 253

- next ›

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools