Features

Away from the imposing skeletons of dinosaurs and whales and the famous Oxford Dodo the Oxford University Museum of Natural History is home to miniature treasures.

These include the jewel-like bodies of bugs in the Hope Entomological Collections, which feature over 25,000 arthropod types. Pull out one of the drawers displaying a fraction of the five million specimens and you’ll be dazzled: despite many of the specimens having been collected in the 19th Century they still shine with vivid colours.

So why don’t the bright blue and green colours of these bugs fade?

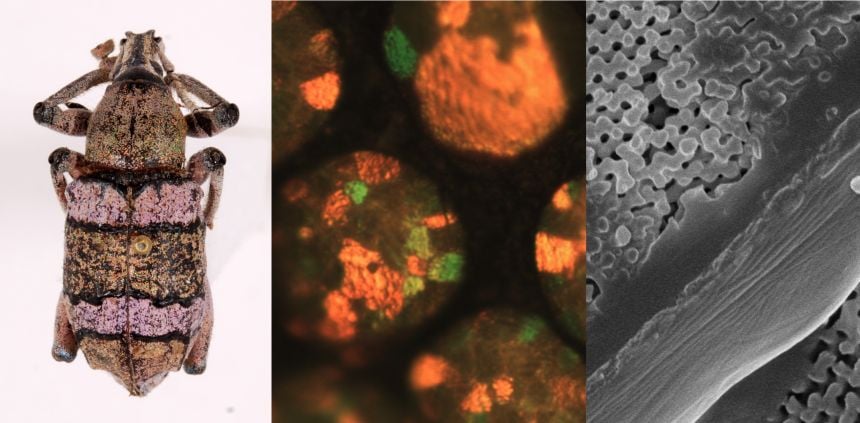

Recent work led by Oxford University and Yale researchers reported in Nano Letters explores how, instead of using perishable pigments, arthropods have evolved ways to create ‘structural colours’ by using tiny structures (100-350 nanometres) that scatter light.

'The most common method to produce vivid and saturated structural colours in insects is using a multilayer or thin-film (like an oil-slick) nanostructure which produces iridescence. Typically, this is formed over the entire surface of the insect, especially the thorax and abdomen (and elytron in the case of beetles),' explains lead author Vinod Saranathan, who undertook the research at Oxford University's Department of Zoology before taking up a new role at the Yale-NUS College in Life Science, Singapore, later this year.

Vinod led the team, which used high energy synchrotron X-rays to examine colour-producing or photonic nanostructures in around 127 species of beetles, weevils, bees, and spiders. They found that diverse groups of these arthropods have independently evolved light-producing or biophotonic nanostructures that are the exact analogues of the complex shapes seen for example, in blends of block-copolymers (large molecules similar to Lego building blocks, having both hydrophilic and hydrophobic ends), but at ten times the sizes usually seen in these synthetic chemical systems.

X-rays reveal the nanostructures the create structural colours

X-rays reveal the nanostructures the create structural coloursHe tells me that OUMNH's Hope collections were vital as: 'a 'one-stop shop' to survey insects and arthropods for structural colour. These historical collections are not only invaluable for my research because of their sheer number (second only to NHM in London) but many of the insects are conveniently organised by the collectors and provide a representative sample of the diversity of insects and other land arthropods. They also have an amazing and growing collection of tarantulas from around the world thanks to Ray Gabriel.'

Whilst, over millions of years, many groups of bugs have evolved to harness structural colours, different arthropod families have come up with their own unique solutions:

'We found in this study that some butterflies, weevils, longhorn beetles, bees, spiders and tarantulas have a very fine covering of scales or hair-like setae (like shingles on a roof) covering the entire surface of the arthropod and these scales (roughly 50-100 microns across) contain a wide variety of colour-producing or photonic nanostructures, from nano-cylinders, -spheres, perforated multi-layers, and complex maze-like, 3D structures such as single gyroid, single diamond, and simple cubic networks,' Vinod tells me. 'However, a given family of insects have evolved to use only one particular type of nanostructure to make colour.

'Despite their diversity, all these photonic nanostructures work on the principle of light interference – as these nanostructures are on the order of visible wavelengths of light, wavelengths that match this periodicity are reinforced and reflected back as the observed colour.'

You might think that these complex nanostructures are confined to complex animals but, Vinod explains, they appear to be innate in the living cells of animals and plants and some of them can be found within the membranes of mitochondria or chloroplasts (they just don’t play a role in making colours): 'Insects and spiders appear to have evolutionarily co-opted this innate ability of cellular membranes to sculpt complex shapes within the cell to make a colour.'

But these nanostructures aren't just of interest to those studying arthropods. Scientists and engineers currently find it very challenging to replicate such complex shapes using chemical polymers at optical length scales and Vinod believes we could learn a lot from colourful arthropods:

'Insects and spiders have been effectively manufacturing these biophotonic nanostructures for millions of years, so we should look to nature to either mimic the same developmental process that gives rise to these nanostructures or use them as direct templates for new photonic technologies and sensors.'

Martin Parr, the renowned documentary photographer, visited the Oxford University Museum of Natural History recently to mark its nomination for The Art Fund Prize for Museum of the Year 2015.

One of his images (above) shows children in a primary school workshop getting their hands on a real dinosaur egg.

He was taken around the exhibits by Scott Billings, public engagement officer at the Museum. A photographer himself, Scott snapped a photograph-of-Martin-Parr-taking-a-photograph (above).

He says: 'Having a Magnum photographer visit the Museum for a photoshoot isn’t something that happens every day, so it was a real privilege to take Martin Parr around the building – in the public areas and behind the scenes – and watch the types of things that caught his eye.

'I am a keen photographer myself, with an interest in the history of photography as an art form. I have a few books of Martin Parr’s work, so it was especially exciting to not only meet Martin and watch him work, but also to photograph the process myself too.

'Anyone familiar with Martin Parr's work will know that his speciality is picking out the behaviours, styles and environments that describe not how we would necessarily like to see ourselves but how we are.

'Subjecting the Museum to the same scrutiny was a little daunting, but Martin captured a combination of images, some with his typical forensic observation and others sympathetic to the beauty of the building and its collections.'

The Art Fund is currently running a photography competition for each of the six nominated museums, asking people to send in their best photograph of one of the museums. Martin Parr will help shortlist six photographers – one for each museum – and then a public vote will decide the winner.

Amateur photographers (or even just smartphone owners!) can upload their photo by Sunday 31 May or Tweet or Instagram it with the hashtag #motyphoto and tag @morethanadodo.

As the final votes are counted and the UK's latest parliament begins to take shape, Oxford University historian Dr Jonathan Healey looks back at 750 years of parliamentary history to pick out what he calls 'the five worst parliaments of all time'.

This is a guest post for Arts Blog. You can see more of Dr Healey's blogs on The Social Historian.

The Bad Parliament, 1377

Doing just what it says on the tin, the Bad Parliament will go down as one of the few assemblies in history that was actually pro corruption.

Disturbed by the damage done by the sanctimonious ‘Good Parliament’ to the garden duck-house industry, the ‘Bad’ decided it befitted the Palace of Westminster to reward courtiers for all kinds of peculatory pilferings. Then, realising there were at least three small buboes in England that they hadn’t yet pissed off, they pulled one of those classic anger-harvesting manoeuvres out of the bag, and imposed a poll tax.

Peasants revolted, nobles were chased out of their mansions quicker than you can say ‘Ed Miliband’, and Richard II had his first serious go at throwing away his crown.

The Merciless Parliament, 1388

Things got even worse with the Merciless Parliament of 1388.

Ruled with sinister glee by the so-called Lords Appellant, the Merciless Parliament was created (one suspects) by forcing a nest of wasps to mate with Katie Hopkins, and cramming their multiple spawn together into a poorly ventilated Wetherspoons toilet.

It made life for its enemies about as much fun as being Eric Pickles’ ham sandwich. Anyone who dared support King Richard II against the Malevolent Appellants found Parliament quickly getting medieval on their ass. Its brutal punishments included hanging, drawing, quartering, beheading, and exile to Ireland.

Fortunately, the people of Kent suddenly noticed they hadn’t rebelled for at least seven years, and went on a well-timed rampage. This forced parliament to concentrate on raising troops rather than lowering life-expectancies, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief. Until…

The Parliament of Bats, 1426

Called to sit in Leicester because it was obviously much more civilised than London, the ‘Parliament of Bats’ came at a time when the nobility’s antics were starting to make Game of Thrones look like an episode of Peppa Pig.

Fearing violence (and improper parliamentary language), the government made the not-unreasonable suggestion that MPs should leave their swords and bows-and-arrows at home rather than bringing them to debates. To the Furcoat Mafia, though, this was just another case of health-and-safety gone mad, so they fired a jet of meady piss in the face of the new rules: arming themselves with a terrifying array of clubs and bats, and turning up anyway.

Worryingly, this fractious Parliament was presided over by a four-year-old (as opposed to someone just acting like one), so it’s nothing short of miraculous that more people didn’t end up under car parks.

The Rump Parliament, 1648-53

Created after a purge , the Rump Parliament is named for its size, though the name’s also an accurate description of what it sat on for four years.

Having, in fairness, significantly reduced the amount of extant Charles I in 1649, the Rump then proceeded to do nothing. Repeatedly.

So addled was the Rump that its MPs spent around eight of their four years arguing about the meaning of the word ‘encumbrance’. No-one pointed out that they could’ve solved the debate by getting a mirror and just looking at themselves. Its only successes came when it started a war with the Dutch out of sheer boredom, and in its brave attempt at bringing the gospel to Wales (though sadly this didn’t have anything to do with gospel music).

Fortunately, Oliver Cromwell was on hand to liven things up. On 20 April 1653, he burst into the house, called a couple of MPs whoremongers, and took away all their baubles. He then brought in a new parliament comprised of religious lunatics and lawyers, though for some reason this didn’t work very well either.

The First Protectorate Parliament. 1654-55

The First Protectorate Parliament followed on from this, and should’ve been brilliant.

Its MPs were only supposed to be those of ‘known integrity’ and of ‘good conversation’. But sadly their rule didn’t live up to their repartee, and they quickly knuckled down to some quality whingeing.

Even after Cromwell barged in (again), and threw a weapons-grade wobbly, they continued in their heroic efforts to be about as useful as a barbed-wire codpiece.

Such was their refusal to do anything vaguely like work that the Lord Protector decided to dissolve them after five lunar months rather than the five calendar ones in the constitution (a UKIP history curriculum would no doubt claim this as a case of his ‘giving in to Islam’).

It meant that Cromwell had now purged Parliament once (arguably twice), and dissolved it prematurely twice (arguably three times).

Naturally his statue now stands outside the modern-day House of Commons.

The 'stiff-legged' walk of a motor protein along a tightrope-like filament has been captured for the first time.

Because cells are divided in many parts that serve different functions some cellular goodies need to be transported from one part of the cell to another for it to function smoothly. There is an entire class of proteins called 'molecular motors', such as myosin 5, that specialise in transporting cargo using chemical energy as fuel.

Remarkably, these proteins not only function like nano-scale lorries, they also look like a two-legged creature that takes very small steps. But exactly how Myosin 5 did this was unclear.

The motion of myosin 5 has now been recorded by a team led by Oxford University scientists using a new microscopy technique that can 'see' tiny steps of tens of nanometres captured at up to 1000 frames per second. The findings are of interest for anyone trying to understand the basis of cellular function but could also help efforts aimed at designing efficient nanomachines.

'Until now, we believed that the sort of movements or steps these proteins made were random and free-flowing because none of the experiments suggested otherwise,' said Philipp Kukura of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry who led the research recently reported in the journal eLife. 'However, what we have shown is that the movements only appeared random; if you have the capability to watch the motion with sufficient speed and precision, a rigid walking pattern emerges.'

One of the key problems for those trying to capture proteins on a walkabout is that not only are these molecules small – with steps much smaller than the wavelength of light and therefore the resolution of most optical microscopes – but they are also move very quickly.

Philipp describes how the team had to move from the microscope equivalent of an iPhone camera to something more like the high speed cameras used to snap speeding bullets. Even with such precise equipment the team had to tag the 'feet' of the protein in order to precisely image its gait: one foot was tagged with a quantum dot, the other with a gold particle just 20 nanometres across. (Confusingly, technically speaking, these 'feet' are termed the 'heads' of the protein because they bind to the actin filament).

So how does myosin stride from A to B?

The researchers have created a short animation [see above] to show what their imaging revealed: that Myosin 5a takes regular 'stiff-legged' steps 74 nanometres in length. The movement resembles the twirling of a dividing compass used to measure distances on a map. With each step the heads of Myosin 5a bind to the actin filament before releasing to take another step. In the animation flying sweets represent ATP, which provides the energy to power the motor protein.

'I describe the motion as a bit like the walks in the Monty Python sketch about the Ministry of Silly Walks,' said Philipp. He adds that we have to imagine that this movement is taking place in a hostile and chaotic nanoscale environment: 'Think of it being rather like trying to walk a tightrope in a hurricane whilst being pelted with tennis balls.'

'We've uncovered a very efficient way that a protein has found to do what it needs to do, that is move around and ferry cargos from A to B,' explains Philipp. 'Before our discovery people might have thought that artificial nanomachines could rely on random motion to get around but our work suggests this would be inefficient. This study shows that if we want to build machines as efficient as those seen in nature then we may need to consider a different approach.'

It seems that if you're designing tiny machines 'silly' walks may not be so silly after all.

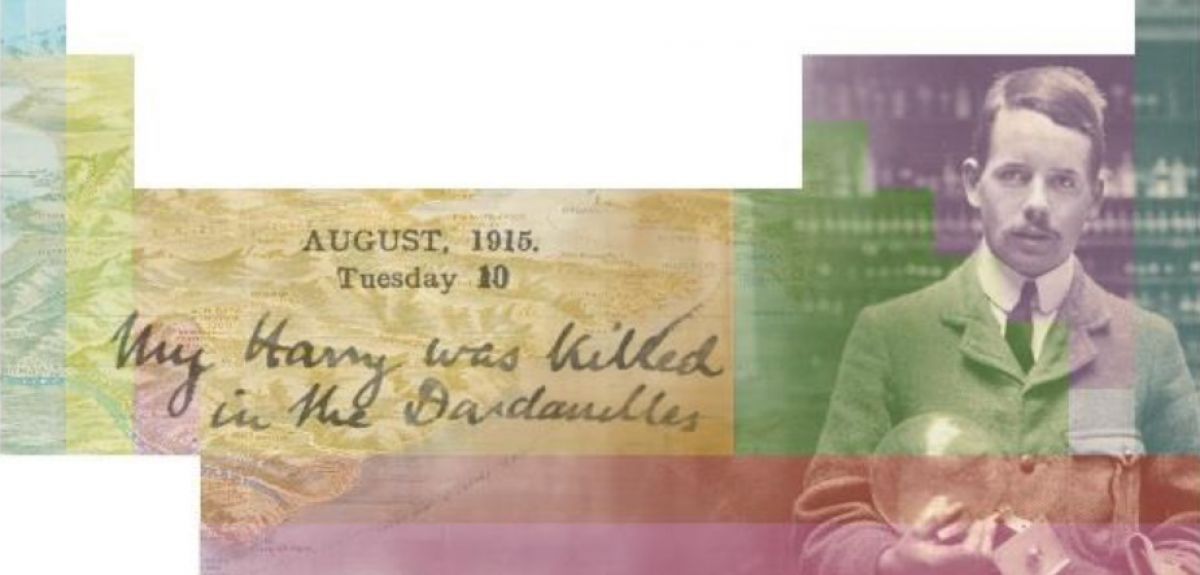

A new exhibition at the Museum of History of Science will tell the story of a promising English physicist killed during the First World War.

Henry 'Harry' Moseley was an exceptionally promising young English physicist in the years immediately before World War I. His work on the X-ray spectra of the elements provided a new foundation for the Periodic Table and contributed to the development of the nuclear model of the atom.

Yet Moseley’s life and career were cut short. He was killed in 1915, aged 27, in action at Gallipoli, Turkey.

With support from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), the Museum of the History of Science is staging a centenary exhibition, 'Dear Harry…' – Henry Moseley: A Scientist Lost to War. This marks Moseley's great contribution to science and reveals the impact of his death on the international scientific community and its relationship with government and the armed forces.

The exhibition opens on 14 May and runs until 18 October 2015.

Using entries from Moseley's mother’s diary, Moseley's original scientific apparatus from the Museum's collections, and his own personal correspondence, the exhibition presents an intimate biographical portrait set against the wider stage of international scientific discovery and World War I.

Through his research and experiments in Oxford and Manchester – where he worked with 'father of nuclear physics' Ernest Rutherford – Moseley made significant and lasting impacts in both physics and chemistry.

Had he lived, the young Moseley was tipped to have been a prime candidate for one of the 1916 Nobel Prizes. Instead, as Isaac Asimov wrote, "in view of what [Moseley] might still have accomplished ... his death might well have been the most costly single death of the War to mankind generally".

The international scientific community was fleetingly re-united in its condemnation of the loss of such a scientific talent, and Moseley’s death led to wider changes in the way that science, scientific research, and scientists were used in war.

Thanks to the HLF’s Our Heritage grant award, the 'Dear Harry…' project will conserve apparatus and archives in the Museum’s collections, permit a subsequent permanent redisplay of this important material, and deliver a broad programme of public events, education work, and digital resources.

The funding has also allowed the Museum to partner with the Royal Engineers Museum, Library and Archive, the Royal Signals Museum, the Department of Physics at the University of Oxford, and Trinity College, Oxford, where Moseley studied. Rarely-seen artefacts from each of these collections will be featured in the exhibition.

'Dear Harry…' has been timed to allow many of the key dates in Moseley's preparations for Gallipoli, and ultimately his death in August 1915, to be presented exactly 100 years later.

A 'live blog', both online and in-gallery, will pick out this centenary anniversary using extracts from archive material to present the events and thoughts of Moseley 100 years to the day.

- ‹ previous

- 151 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria