The Ruskin School of Art

'At the Ruskin School of Art, our research programme includes cross-disciplinary commissions with established and emerging artists. We bring artists to Oxford so that they can work with different faculties across the University.'

I'm speaking to Paul Bonaventura, Senior Research Fellow at the Ruskin School of Art. I want to find out from him about a new commission that marks the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta – how a contemporary artistic interpretation of the Great Charter brings to the fore how differently we treat historical documents and digest information in a digital world – and hear more generally about the Ruskin’s work and his role in it.

'Some years ago I realised that the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta was fast approaching. I also realised that Oxford held four of the last remaining copies of the document and counted among its academic staff a wide range of subject experts. So I approached individuals at the Bodleian Library, Faculty of History and Faculty of Law to see if they might be interested in working with the school on an anniversary commission and put together a collaborative proposal for the British Library. The British Library holds two of the four remaining examples of the 1215 version of Magna Carta and has been working towards a landmark anniversary exhibition for several years.

'Once I'd identified the research base in Oxford, established the partnership with the British Library and raised the funding, we went about the process of identifying an artist, approaching individuals whose work revealed a pre-existing interest in politics, history or law. In the end we selected Cornelia Parker for her proposal to produce an embroidered facsimile of the Wikipedia article on Magna Carta as it appeared on the document’s 799th anniversary.

For Cornelia, the Wikipedia article carries with it an echo of the document itself.

'For Cornelia, the Wikipedia article carries with it an echo of the document itself. It sits somewhere on the boundary between authority and democracy and is the product of many hands.

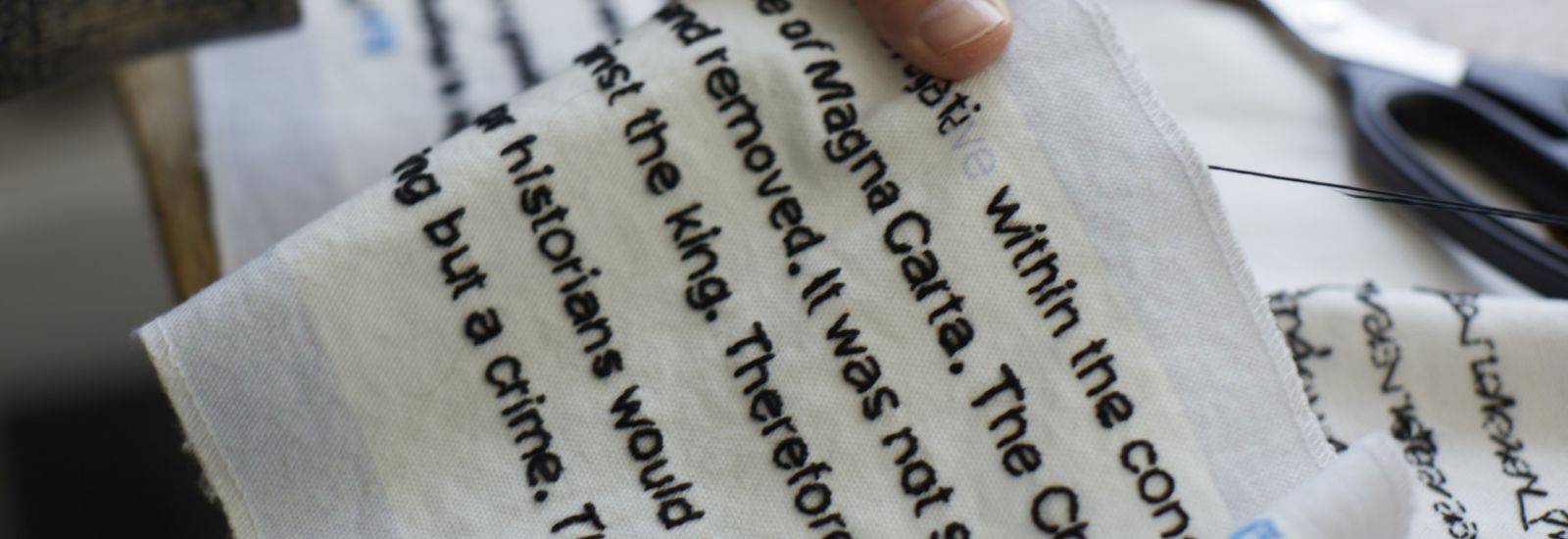

'In order to produce the artwork we took a snapshot of the article on 15 June 2014 and output it on fabric. The fabric was then divided into panels and sent out to contributor-stitchers all over Britain. Once the panels are completed they will be sewn together to generate an analogue copy of the digital original.'

Are people doing the embroidery metaphorically significant?

'We are working with a number of project partners on the commission: The Embroiderers’ Guild, Fine Cell Work (a social enterprise that trains prisoners in paid, skilled, creative needlework), the Royal School of Needlework and Hand & Lock. The images that appear on the artwork have all been embroidered by members of the Embroiderers’ Guild, but most of the text has been stitched by prisoners. There are only three clauses from a later reissue of Magna Carta that remain on the statute books and the most famous of these is the clause that underpins the Rule of Law.

Cornelia Parker working on Magna Carta (An Embroidery) - Photograph Joseph Turp

Cornelia Parker working on Magna Carta (An Embroidery) - Photograph Joseph Turp'But of course Magna Carta has an impact on everyone and Cornelia wanted this to be reflected in her artwork, so she assigned individual words and phrases to people from all walks of life: judges and lawyers, campaigners, clerics, artists, musicians, academics, librarians. The fact that no one is above the law is one of the driving conceptual forces behind Magna Carta (An Embroidery).'

Getting all those bits of embroidery to different people and back again must have been a complex process. What role does contemporary art play as a medium for public communication?

'Art is a broad church and I’m particularly interested in those artists who are trying to access audiences outside of the museum and gallery sector; those artists who produce work that naturally finds a home in other parts of the public domain.'

He gives me an example of a piece that was local to Oxford.

'Some years ago we did a project with an artist called Richard Woods. Richard makes over the interiors and exteriors of buildings using cartoon graphic devices. In partnership with New College we arranged for Richard to give one of their best-known historical buildings – the 14th-century Long Room that looks on to Queen’s Lane – the "red brick" treatment. A project like NewBUILD is inherently site-specific.'

NewBUILD, Richard Woods' reinterpretation of New College's Long Room

NewBUILD, Richard Woods' reinterpretation of New College's Long Room

The Ruskin is an art department within a vast academic university. What does that add to the study of fine art?

'Artists are interested in working across disciplines. Until recently most art schools were standalone organisations, but the Ruskin has always been a university-based art school. What that means is that it sits alongside the humanities, the social sciences, the natural sciences – all of the subjects that are represented across the University. In terms of developing the research programme that gave me permission to think about bringing artists together with experts from other faculties.'

You've touched on the history of the Ruskin – can you tell me more about it?

'The school was founded by John Ruskin in 1871 as a school of drawing. It was set up on the basis that if you could read, write, draw and were numerate you had all the tools you required to make sense of the world. As time went on, the drawing school became a school of fine art. The undergraduate degree only acquired honours status in the early 1990s and its programme of postgraduate study is a fairly recent development.'

How did you come to be Senior Research Fellow at the Ruskin?

'I originally started out studying science, but moved across to study the history of art and architecture. After I graduated I became as an exhibitions organiser, firstly at Modern Art Oxford and then at the Whitechapel Gallery. In Oxford and London artists were saying "It’s fantastic to exhibit here, but can you help me have a conversation with a meteorologist or an organic chemist?" That prompted me to think about establishing some kind of research programme that would allow those conversations to happen. I approached Stephen Farthing (Ruskin Master of Drawing 1990–2000) to see whether he might be interested in such a programme and he generated a new post expressly for that purpose. This is the post I currently occupy.'

As well as the Cornelia Parker commission, the Ruskin is currently touring the outcomes of another commission called Shot at Dawn, which is the work of the young British photographer Chloe Dewe Mathews. How did this piece come to be?

'In 2012 Chloe expressed an interest in producing a new body of work that focused on the sites where British, French and Belgian troops were executed for cowardice and desertion between 1914 and 1918. Sir Hew Strachan, Chichele Professor of the History of War and one of the country’s great experts on the First World War, provided the project with detailed support from the outset and put Chloe in contact with academics and independent researchers who could assist her with her research.

Shot at Dawn on display at Stills - Scotland's Centre for Photography in Edinburgh - Photograph Chloe Dewe Mathews

Shot at Dawn on display at Stills - Scotland's Centre for Photography in Edinburgh - Photograph Chloe Dewe Mathews'The success of the Ruskin’s research programme all comes back to it being the fine art department at the University of Oxford. If artists can find an approach to a subject that is equally interesting to academics in other areas then the conversation will unfold organically. Good projects help individuals from all walks of life to reassess their activities. In the best cases the collaborations help artists to develop new work from a sound research base, but they also help academics to look at their subject in a new way.'

Finally, what gives you most job satisfaction?

'Hopefully, making a difference.'