Professor Paul Newman

'I think from my earliest memories I was going to be an engineer – I’ve always been fascinated by things moving and seeming to take action by themselves,' Paul Newman tells me.

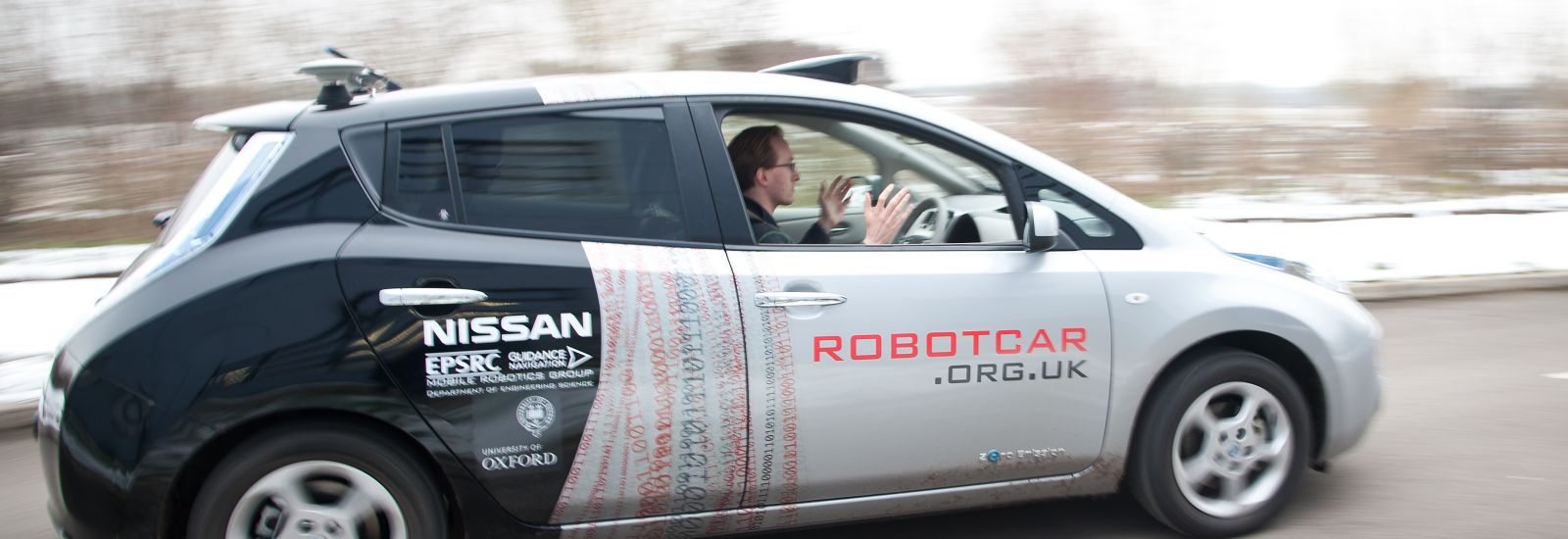

Paul is BP Professor in Information Engineering at the University, and heads up the Oxford Mobile Robotics Group (MRG), and its spin-out ‘Oxbotica’. The interview takes place in MRG’s offices on Banbury Road and discusses the world of mobile robotics, what’s being developed at Oxford and about Paul’s academic career, motivations and future objectives.

Where did the initial interest in robotics come from? And how did that lead, some time later, to your being in Oxford?

'I came up and read engineering here in 1991, and through it began to put myself on a trajectory for robotics. Robotics is the intersection of lots of interesting things: some maths, some electrical, some design, some software, some mechanical, some systems. What happens if you stick a robot on a reef? It’s really difficult to stick machines in environments that we find trivial. That’s always fascinated me. A second addiction I have is having machines do things that are useful to people. What became really delightful for me was when I realised the magic sauce was software: lots of people can build the electronics, lots of people can do the mechanics, but it's the software and the algorithms that really make these machines fly. And what’s really going to make the difference is embedding your intent and ability to learn in software.

'Oxford’s a brilliant place to feed that. We get really smart people working here, we’ve got a great place to work - the University really gets behind this stuff. I really got lucky coming back to be able to build something like this here in Oxford.'

How has the world of software engineering changed from when you first started out?

'Relatively recently, in the past three years, it's become trivial to store everything. It used to be the case that you had to be extremely careful about what you stored, because you had a rubbish floppy disk. Now you can store everything. And that’s made a big difference to the kinds of approaches we’re taking in our algorithm development. Every time one of the cars we’re working on goes out, we can store everything it saw. We don’t try and extract just the little interesting things, we log it all. That’s allowing us to develop very different kinds of algorithms that learn every time they go out. I think that’s really exciting.

During this interview, computers just got better. The numbers are just staggering – yesterday we sent 100 times more data between ourselves as a civilisation than all the words that have ever been spoken. 10% of all photos were taken last year. It’s just extraordinary. And robotics, like so many other things, will surf that and benefit that.'

A lot of this has strong relevance to industry: were you always entrepreneurially minded, or did the partnership with industry happen organically?

'I’m an engineer – if I build something, it’s got to be valuable. I work best when someone says, "I’d like something to do this". Then I’ll set myself a goal of a competency that I would like a machine to have – and I’m very much driven by that: I’d like a machine to figure out where it is on a motorway network without GPS, or I’d like it to operate in a kilometre-long warehouse in the dark.

'And that’s how all our flagship programmes come to be, like the driverless cars and Mars rover. Each of them is anchored to a particular industrial sector that has particular challenges, but it's all the same competencies of robotics: where am I, what’s around me, what does that mean for what I should do next?'

How much day-to-day involvement do you have with your spin-out company, Oxbotica?

'We care about this a lot. It’s helped that the University has been very positive in the way its thought of and understood Oxbotica. The University has recognised how Oxbotica, rooted in the research of the Mobile Robotics Group, can help other companies understand how to take this technology and deploy it themselves. The business model of Oxbotica is based on mobile autonomy, but we’re not going to be making Mars rovers or logistics vehicles. We want to find partners who do that already.'

What do you think the most exciting prospects in robotics will be in the next five years?

'People cottoning on to mass connectivity and mass data. And here’s why: imagine a machine that’s started for the first time, and compare that to a human that’s started for the first time. A human baby has brain structure that means its arms are going to move in approximately the right way – and there’s all kinds of hardware that’s been set up to do that. But your experience of learning from the world is down to you, it’s up to you to hit things, fall over things, cry. But not so for the machines: when the machines start turning on, they might have access to every image that has ever been taken by other machines, instantly, even though they haven't directly ‘experienced’ them. Now that’s something different that organic machines don't have. That is very, very interesting and it’s going to start coming through in the next few years.

'For example, the pods we’re building – they’re going to have access to the decisions, perceptions that all of our machines have made up to this point.'

Have you any sense of what the tangible output of that will be for the consumer?

'Better machines. We’re never going to have dumber machines. Computers just got better again since we last said it, and we’ve never been recording more stuff. The printing press was exciting, but compared to what will happen when everything can communicate with everything else… that’s just extraordinary.'

What kind of skill set do you think helps to get into robotics?

'Programming. Learn to programme when you're five.

'For as long as we confuse computing with using the print dialogue box, we’re doomed. We must not confuse using a computer with generating software and algorithms. The brilliant thing about software is that it’s weightless – it’s just text files – that’s where we really must lead in this country, and we’ve drifted. When I was seven, at school we had a BBC Micro. And at lunchtimes we could play on this computer. The fact I could now go into a school and see no computers is weird. Where is the programming? Computers are astronomically better, but most people are completely removed from it. That’s a disaster and we really need to fix it.

'You write a text file, and something moves on Mars – that is empirically cool. We need to be getting these skills in our syllabuses. And computing isn’t hard – it’s easier than French. Have a go – what can go wrong?'

Have you any idea what you would like the legacy of your work to be many years from now, when you pack up?

'I’m going to go to Mousehole – it’s a fishing village at the end of Cornwall. It’s where it all started for me and I learnt to swim. I will go to Mousehole and I will build robots. I will have a workshop and I will build the robots I want. That’s a long, long time away.

'The wonderful thing about academia is that it all gets mixed up. Rarely do you get the privilege and the honour to be the single guy to be associated with something. I would never expect that that would be something that happens to me. You contribute, you shape the questions and other people answer the questions you asked. Here’s the interesting thing: you write a paper and you say "We had a problem, and we solved it in this way". And then someone else comes along and says "Hang on, we think you messed up here, and so that actually influenced the thing we did in the next year". Isn’t that an interesting second order way that things are influenced?

Your greatest successes are when your biggest competitors take your idea – when people use the ideas that you have.

'That’s another lovely thing about academia – your greatest successes are when your biggest competitors take your idea – when people use the ideas that you have.

'One of the great things about working in the University and with the Knowledge Exchange team – people who’ve willingly given their time – in particular Phil Clare (Associate Director, Knowledge Support and Head of Knowledge Exchange) and Stuart Wilkinson (Head, Knowledge Exchange and Impact Team [KEIT]) – because they know it’s strategically important to have academics understand how to contract and work with companies, such that you can fulfil the academic mission, and get stuff out there so that the companies want to work with you. That’s been great, and I would never have expected I’d enjoy that stuff so much. We want to make stuff, companies want to make stuff and make money – they’re not separate objectives, and there's a toxicity in thinking that they are.'

How does the tech and innovation coming out of Oxford compare to the UK nationally?

'I think it's fair to say we lead in mobile autonomy. What’s great is there’s a cracking community in the UK for robotics. I’m proud of what we’ve managed to bring together and then in representing this domain to government.'

What gives you most job satisfaction?

'That’s really difficult. Because there is three axes – there’s figuring out an idea that's going to make something work in a way that didn't before. Then there’s the joy I get from seeing any number of different pieces of work pulled together on a vehicle – that’s extremely satisfying. It’s not one competency, it’s ten all pulling together. Running a research group is not just about the science; it’s about working with people who are very, very clever people and have all kinds of different personalities – I find it fascinating trying to bring all that together.

'And thirdly, setting up this building. I come up here at seven in the morning, when no one's here. I walk around all the DPhil desks, see what’s going on. To see the lab when it's still and quiet and think what’s come out of this is absolutely fascinating.

'I think the other axis is – where am I personally happiest, where do I get persistent joy? That's when I’m writing those text files – which I was doing before you came in. That’s where I feel personally creative. And I’ll do that full time at Mousehole one day.'