Combating drug-resistant malaria

Oxford University research has contributed to strategies to eliminate malaria in the Greater Mekong Sub-region, helping to prevent the spread of drug-resistant malaria and improving health provision and outcomes for remote communities.

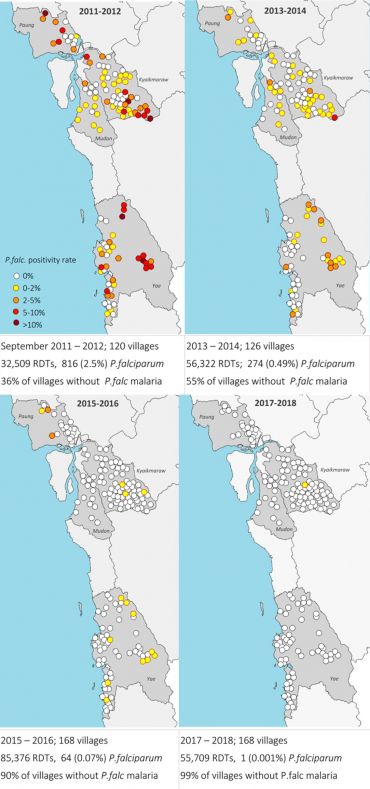

In the Mon state falciparum malaria was eliminated within 6 years. Only 1 out of 55,709 people complaining of fever tested positive. He was a soldier from another region, who visited his family in the Mon state. © MORU 2020.

In the Mon state falciparum malaria was eliminated within 6 years. Only 1 out of 55,709 people complaining of fever tested positive. He was a soldier from another region, who visited his family in the Mon state. © MORU 2020.Although attempts to tackle the disease through prevention (insecticide, mosquito nets) and treatment (early diagnosis and drug therapies), have helped reduce cases in the early 21st century -the burden of disease is now rising again in Africa.

In contrast over the last decade, cases have gone down drastically in the Greater Mekong Sub-region (GMS), where Oxford University has a long track record of research and health collaboration, and has been working to tackle the spread of new strains of drug resistant malaria.

The GMS is a trans-national area encompassing parts of countries that share the Mekong River: Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Lao People's Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), and parts of China.

This trans-national area, which encompasses countries that share the Mekong River, saw the emergence of drug resistant malaria in Cambodia from the 1970s. Drug-resistant parasites have previously spread from the GMS to Africa, killing millions of children, and more recent artemisinin resistance (a key drug in combating malaria) threatened to spread in the same way.

Research and engagement

An initial (2011-13) tracking of artemisinin resistance (TRAC) study across ten GMS countries demonstrated the wide spread of the resistance problem, prompting an urgent need for measures to prevent further spread. At the same time further research suggested that asymptomatic malaria infections were a key source of malaria transmission.

This indicated that interventions should go beyond treating just symptomatic cases and should aim to eliminate all malaria in the region, through the mass administration of antimalarial drugs to target populations, even where there was no obvious evidence of the disease.

“It was clear that we needed to do something radical to prevent the spread of drug-resistant malaria… to fight fire with fire,” says lead researcher Professor Sir Nicholas White. “Initially there was quite a lot of resistance to mass drug administration (MDA), which was not the normal practice. Health agencies feared it would itself promote drug resistance, that it would be costly and difficult to administer, and that it would be unacceptable to local people. In fact, by working closely with communities we managed to gain their trust and engagement and prove that not only was MDA safe – it was also very effective.”

Many villages in the region are extremely remote and difficult to access except by foot or off-road vehicles. Infrastructure and health provision are usually poor, and refugees and migrant workers, who make up a significant part of the population, have particularly poor access to healthcare.

“But we identified respected members of the community in each village in the areas where we work, to train as informal health workers,” explains White. “They acted as focal points for testing, diagnosis and drug distribution, which meant that people were usually happy to participate in the programme.”

Malaria used to be the main cause of hospital admission along the border but it is now a rarity.

The community health workers were also able to offer a basic health care package, including treatment for malnutrition, diarrhoea, and respiratory tract infections, ensuring that local people with other health conditions received diagnosis and treatment, and that people continued to seek health care even after malaria cases had dropped.

Overall the programme, transformed the health of local communities with a population of more than 1,000,000 people, and successfully prevented the spread of drug-resistant malaria.

The programme was also successful in influencing international policy on tackling malaria.

“The World Health Organisation were initially opposed to the idea of mass administration of drugs to healthy populations, and indeed, the need to completely eradicate malaria in the GMS – where the disease is much less significant a burden than in other areas of the world,” says White.

“But the evidence from the Oxford programmes was very clear and helped to shift their policies, and those of other international health agencies, who are now directly implementing these programmes to tackle drug-resistant malaria.”

Professor Sir Nicholas White is Professor of Tropical Medicine at the Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health.

Research Team

Nicholas White Professor of Tropical Medicine, Chairman, Oxford Asian Tropical Research Units; Nicholas Day, Professor of Tropical Medicine, Director, Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), Thailand; Arjen Dondorp, Professor of Tropical Medicine. Deputy Director and Head of Malaria, MORU; François Nosten; Professor of Tropical Medicine, Director, Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU), Thailand & Myanmar; Frank Smithuis, Associate Professor, Director, Myanmar Oxford Clinical Research Unit (MOCRU); Lorenz von Seidlein, Associate Professor, Senior Researcher, MORU.

Research Centres

Research has been led by the University of Oxford Nuffield Department of Medicine, Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, working with the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) and Myanmar Oxford Clinical Research Unit (MOCRU) in the Greater Mekong Sub-region.

Funders: Wellcome Trust, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Medical Research Council (MRC), Program for Appropriate Technology in Health, Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV)