Setting the agenda for the next century of quantum

Ian Walmsley, a Professor of Quantum Science and Engineering and an internationally recognised expert in quantum photonics, has returned to Oxford from Imperial College London, where he served as Provost for the past seven years. He was previously Hooke Professor of Experimental Physics and Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research and Innovation at Oxford. His career has seen him lead the UK’s first Quantum Technology Hub, co-found a quantum computing spinout, and serve on the UK Government’s National Quantum Strategic Advisory Board.

In October this year, he took up the position of Director of the Oxford Quantum Institute (OQI). Here, he reflects on Oxford’s strengths in quantum, the role that the OQI will play to accelerate impact, and how the UK as a whole can remain competitive in the quantum arena.

Your career has ranged across both fundamental and applied quantum science. What first drew you in?

There is a huge opportunity for quantum here in Oxford and a will to succeed. I look forward to getting the Institute underway and collaborating with brilliant colleagues working at the cutting edge of quantum.

My route into quantum was through optical science and engineering - using light as an exquisite sensor to probe systems, to link systems for secure communications, and increasingly to process information in photonic quantum computers. Light is special: it is the one physical medium we can control with extraordinary precision in which quantum effects remain accessible at room temperature. That makes it both a powerful scientific tool and practical technology, with a unique ability to bridge disciplines from astronomy to biomedicine.

I’ve had the good fortune to work with brilliant colleagues across many domains of optics and photonics, but particularly at the conjunction of ultrafast and quantum optics. This combines producing very, very short light pulses with the science of how light behaves according to the rules of quantum physics. One of my earliest directions was to use the brevity of ultrashort light pulses to map the quantum motion of vibrations in molecules, and later to make two diamonds sitting in the lab become “entangled” – meaning their properties became linked in a way that goes far beyond anything possible in everyday, classical physics.

Part of this effort required developing new tools to measure and fully characterise these very brief events, and that led to a commercial device that was used to ensure this category of lasers were performing as you wanted. More recently we’ve used this domain to generate the purest single photons yet made, and enabled quantum photonic platforms for information processing – elementary quantum computers, in fact, though far from a scalable machine.

How has the field of quantum computing changed over your career?

If we can harness the power of superposition (where units of information can exist in indeterminate states), this would unlock computational power far beyond that of classical computers.

Quantum science has been around for over 100 years, but the last two decades have been truly transformative. The key tipping point was the realisation that applying quantum principles to the transfer of information could be a reality and not just a theoretical possibility – unleashing the current intense development effort across engineering and physics. We can now conceive how quantum principles could be used in the future to perform useful work and solve problems.

If we can harness the power of superposition (where units of information can exist in indeterminate states), this would unlock computational power far beyond that of classical computers. As Bill Phillips (1997 Physics Nobel Prize winner) said: ‘A quantum computer is more different from today's digital computers than those computers are from the abacus.’

What is the aim of the Oxford Quantum Institute?

Our aim is to ensure that Oxford fulfils its potential as one of the world’s pre-eminent institutions for researching both fundamental quantum technologies and their impacts on society. Oxford already has exceptional quantum capabilities distributed across many departments; OQI adds value by joining these up. By coming together, we can develop shared concepts and language across disciplines to identify the really big questions and new ways to answer them.

The Institute will have a dedicated space in the Townsend Building to act as a common meeting point for both our diverse research community and external luminaries – from those working in technology governance at Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government to biochemistry researchers using quantum to study the structure of enzymes.

No known physics forbids fault-tolerant quantum computers, but the technical challenges are formidable.

OQI will also serve as a ‘shop window’ of Oxford’s quantum capabilities to the wider world, providing a portal of access for external institutions to look through to see how they might access these strengths. The exchange of ideas is critical to drive forward research, and OQI will actively work to create opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaborations. A central aim is to create joint research partnerships that allow academics to move seamlessly between universities, research centres, and industry, gaining broad insights that enrich their work.

In short, the goal for the OQI is to set the agenda for the next 100 years of quantum science.

Where does Oxford stand in quantum right now?

Oxford has one of the deepest and broadest concentrations of quantum expertise anywhere, from thinking about the philosophical foundations of the theory to developing the technology for quantum computers and spinning out companies that are already commercially applying quantum principles. The University has played a leading role in the first three generations of the UK’s Quantum Hubs network and has had a large influence on the national agenda. For instance, Oxford is a key partner in the UK's first Quantum Biomedical Sensing Research Hub, launched last year, which is exploring how quantum technologies could transform early disease diagnosis.

At the same time, Oxford is really pushing at the frontiers of fundamental science. For instance, the QUEST-DMC experiment, in which Oxford is a key partner, is using the quantum properties of superfluids as a super-sensitive detector for dark matter. And the AION consortium is using atom interferometry with a similar aim. This is led by Imperial and Oxford, with the next generation large-scale interferometer hopefully to be built here.

It’s this combined breadth and depth that makes Oxford such a stimulating place to be in quantum.

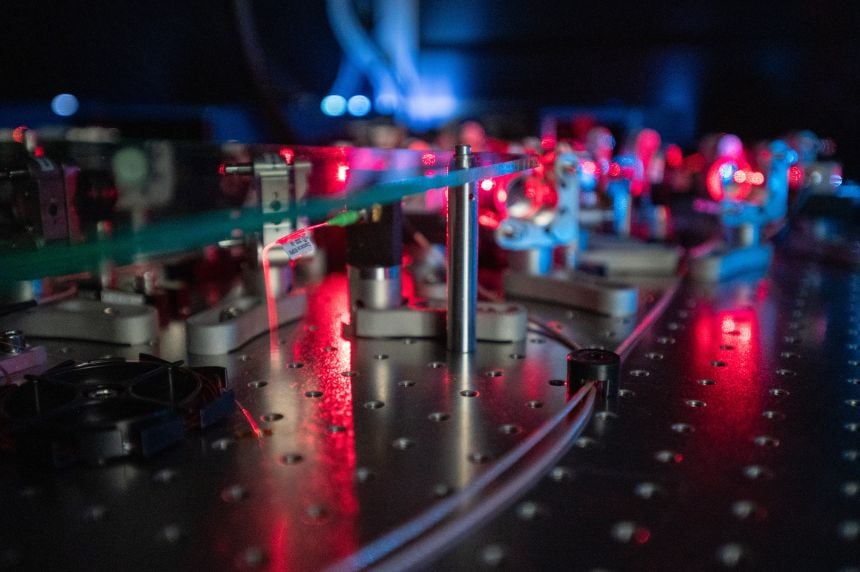

Quantum research at Oxford University. Credit: John Cairns.

Quantum research at Oxford University. Credit: John Cairns.How long will it be before we have a fully working quantum computer?

How long is a piece of string? The underlying technology for quantum computing has developed rapidly over recent years, and quantum concepts will soon start to impact our everyday lives, for instance room-temperature MRI sensors for brain imaging and ultra-secure communications over a quantum network. No known physics forbids fault-tolerant quantum computers, but the technical challenges are formidable. Until these are addressed, it is still a case of if not when we get to functional fault-tolerant quantum computers capable of realising the full promise of the technology. I am sanguine that we will eventually get there, but that we’ll probably need a few more creative ideas to do so.

Nevertheless, with so much resource being applied to this goal, we can be confident that the journey will result in ‘spin off’ benefits along the way. We can expect hybrid quantum–classical co-processors that can slot into data centres, boosting certain AI and optimisation tasks, sometimes with lower energy or higher accuracy. Another likely application is navigation with quantum accelerometers and gyroscopes that can work in GPS-denied environments. Sensitive quantum probes of sub-surface structures and long-distance quantum key networks are also in commercial prototype stages.

Tell me about your quantum spinout, ORCA computing.

The exchange of ideas is critical to drive forward research, and OQI will actively work to create opportunities for cross-disciplinary collaborations across academia and industry.

I co-founded ORCA Computing in 2019 as a spinout from the first Quantum Computing Hub, which was based here at Oxford. My co-founders were Professor Josh Nunn at the University of Bath, one of my former DPhil students and research colleague, and Dr Richard Murray, from Teledyne, who we met through the first Quantum Hub when he was at Innovate UK - another example of how initiatives that bring academia and industry together can bear unexpected fruit.

Our aim was to apply what we had learned from more than a decade of research at Oxford toward building a flexible quantum computer powered by photonics. The machines we produce store and process information using individual particles of light (photons) travelling through standard optical fibre, rather than electricity. These can plug directly into existing data centre infrastructure to enable organisations to try real-world tasks – such as optimising complex networks or experimenting with AI/machine learning workflows- by running quantum and classical computing side-by-side in a hybrid manner.

We now supply photonic computers for machine learning to a range of international customers including the UK Ministry of Defence, the UK’s National Quantum Computing Centre (UK), and Montana State University (US).

Oxford’s spinout track record in quantum is strong, but what is the outlook for quantum commercialisation in the UK?

The UK is well positioned to develop commercial quantum applications. The UK National Quantum Technologies Programme, which has been in place for 10 years now, has really been a spur to bring together the great scientific ideas based in universities and real-world, user knowledge within industry. The intersection of these has already launched a wide range of quantum spinouts and Oxford has been particularly prolific.

Oxford has one of the deepest and broadest concentrations of quantum expertise anywhere, from philosophical foundations to developing technology and spinning out companies.

However, two things are crucial to ensure that the UK can capitalise on this. First, investing in the skills base. Universities play a vital role in developing highly talented people, but our efforts are compromised if the UK is not seen as open and attractive on the global stage. We need to actively engage with policy makers to ensure that immigration policies and visas, for instance, are aligned with national quantum goals.

The second issue is finance. In the UK, there is a definite funding gap between the stages of launching a seed company and developing the technology to the point of market-readiness. Here in Oxford, we can benefit from investment from Oxford Science Enterprises, but the UK Government needs to think hard on how to attract more venture capital money into the UK quantum ecosystem as a whole.

Do you have a favourite example of a quantum spinout launched at Oxford?

Of course, I’d be bound to say ORCA Computing! But there are many successful companies to choose from. The recent sale of Oxford Ionics based on their trapped-ion gate technology was clearly an outstanding success, and a global endorsement of Oxford’s capacity for creating world-leading tech companies. I’m generally quite fond of all those quantum computing businesses that emerged from the first two Hubs: Oxford Quantum Circuits, Quantum Motion, and Universal Quantum prominent among them.

You can find our news items on quantum-related research at Oxford University here.

For more information about this story or republishing this content, please contact [email protected]

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era