Features

Eleanor Stride has taken an unconventional path to becoming one of Britain’s leading scientists. She tells Sarah Whitebloom how she moved from dance to design and onto biomedical science, but being a 'woman in science' is not one of the identities she seeks.

When is a woman in science not a ‘woman in science’? When she is a woman in science.

At the risk of generalisation, women in science are hard-working, dedicated, cutting edge…scientists. Call them ‘women in science’ at your peril. Women in science will tell you quite firmly that they do not want to be treated differently or feel they do not deserve their place. Any hint of tokenism will be greeted with a frosty response.

Although science needs more women, it needs more people, a diverse range of people, with different perspectives and ideas.

And Professor Eleanor Stride is an uber scientist, which is nothing to do with mini-cabs but everything to do with dedication, hard-work and world-changing ideas. It is hard to imagine that she has ever felt she is making up the numbers.

‘You’d be surprised,’ she says. Sometimes, it is felt that there has to be a woman involved and no one wants to be that woman. Professor Stride maintains there is, of course, a need for more women in science and is infuriated at the idea that girls are still told that Maths and science is not for them. She is, quite literally, furious at the ‘Mummy wasn’t any good at Maths’, sort of parental advice. And, she says, the counter-balance needs to start early, at Primary School, when girls start to drift away from the sciences and Maths.

Professor Stride, herself, had not intended to go into science or engineering and certainly not Biomedical Engineering. She actually started her education in a ballet school and progressed through school without a thought of going into sciences. It is a life she has not quite ever left behind and even now Professor Stride is involved in dancing – as a teacher of swing dancing in Oxford.

You’d be surprised how many scientists are involved in dance. I think it’s something to do with being very technically focused and frankly a little bit obsessive.

Thanks to a series of chance events - and a lot of obsession - today, as well as a dance teacher, she is also the Professor of Biomaterials, with a joint position between Engineering Science and the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Science - and there is a real buzz around her work.

It is a few years off, but the work being done by her team may just revolutionise cancer treatment – using tiny bubbles and ultrasound to deliver targeted treatments inside the body. And the self-effacing Professor Stride has won so many prizes for this work, most recently the Blavatnik award (her ninth), she is almost embarrassed. While grateful for the recognition, she emphasises she is part of a team and muses on an idea in circulation that Nobel prizes will not continue in their present form, because science now is so collaborative that individual prizes do not make sense.

Thanks to her unconventional route, Eleanor Stride is something of a one-woman collaborative team. Unsure at 18 what she should do, young Eleanor was taking science ‘A’ levels, but also Art and Latin when she underwent a Pauline conversion to engineering. So impressed had she been by a chance visit to a design exhibition, organised by her Art teacher, she promptly decided her destiny lay in making things. She was inspired to take a degree in Mechanical Engineering at UCL and she intended to follow up with a Masters course in industrial design at the Royal College of Art.

As with all best-laid plans, though, it did not happen. In her final Undergraduate year, Eleanor became interested in the impact of ultrasound on bubbles – in oil pipes. From there, thanks to a meeting in the senior common room between her supervisor and a senior radiologist, she ended up abandoning her plan to be an industrial designer and did something completely different - a Biomedical PhD on the use of bubbles in ultrasound imaging.

‘Bubbles in pipes are like bubbles in the bloodstream,’ she says. If you could use those bubbles and ultrasound, to deliver cancer treatments to the place it is needed, rather than injecting the whole body with heavy-duty drugs, you could revolutionise the battle against tumours, even hard to reach ones.

Although it seems a long stretch, to go from wanting to work for Aston Martin to drug-delivering bubbles, Professor Stride insists it is an engineering delivery problem.

‘The bubbles are just like very tiny cars,’ she says. ‘And we are working on the delivery process.’

It was not quite that easy, of course. Professor Stride did have to play catch-up during her PhD years, taking classes in anatomy at the medical school and learning, for the first time, about biology.

‘It is more complex but the approach is not that far-fetched,’ she maintains.

As a Mechanical Engineer with the know-how of a Biomedical Engineer, Professor Stride’s background is attuned to solving the problem - along with a host of experts from other disciplines from Physicists to Biologists and Chemists. As a team, they bring together the broadest range of experience and expertise. And Professor Stride laughs as she admits there is some truth to the science hierarchy portrayed in the American TV series, The Big Bang Theory, where the engineer is the butt of jokes.

At the top are the pure Mathematicians. Some way down are Theoretical Physicists and some way below them are Astro-Physicists. Next come Electrical Engineers and then come Mechanical Engineers, then Biomedical Engineers!

So you went down the ranking when you transferred to Biomedical and took your PhD?

‘Yes,’ she says, with amusement. ‘But then come Civil Engineers and Architects … only joking.’

Professor Stride laughs at the stereotyping, especially as her father-in-law was an architect.

‘Engineers are looked down on because they are dealing with real world problems. They make things work and sometimes that means making compromises,’ she says wryly.

Having engineers on board has brought closer the possibility that work of Professor Stride and her team will result in real advances that could save lives. The irony is clearly not lost on her. But now, she admits, the really hard part begins. The team is very close to being in a position where they will be ready to begin clinical testing. This is her next big challenge, her next career shift.

Turning herself yet again into something else, the good Professor is currently becoming accustomed to giving presentations to groups of venture capitalists and people who might possibly donate money. Without this, all the positive lab results will come to nothing.

‘The cost is phenomenal,’ she says, describing the arduous and complex procedures that now have to be gone through before their work has a possibility of reaching patients and making a difference.

‘Some people have been very generous, but there is a lot more money to raise,’ she says.

It is a lot to ask, Professor Stride realises it is a risk for an investor, when there is only a one in ten chance that it will work. And there are vested interests in it not working, given the existing treatments that could be undermined by tiny bubbles.

But, says Professor Stride, for all the prizes, she will not feel as though she has succeeded until all this work has helped someone.

Hear Professor Eleanor Stride speak about the future of science

Game Changers: 9 Young Scientists Transforming our World

When: Thursday 5 March, 2020, 11am–6pm

Where: Banqueting House, Whitehall, London, UK

Event: Hosted by BBC News Science Correspondent Victoria Gill, this public series of short, interactive talks from early-career UK scientists, including Professor Eleanor Stride, will provide a forum for science enthusiasts to discover cutting-edge research that is shaping the world. Following the talks, a discussion will explore trends and insights influencing the future of science in the UK. Attendance is free and open to the public, but registration is required.

Register for free: www.nyas.org/YoungScientists2020

The latest in our ScienceBlog series of 'amazing people at Oxford you should know about' is Dr Pavandeep Rai. A Post-doctoral Research Scientist in the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, her work focuses on the effect of something called 'mitochondria' on Parkinson's disease, using cutting edge gene-editing cool CRISPR-Cas. Here she guides us through her career and experiences of pushing the boundaries of science in both research and art...

To start with, can you give us a beginner’s guide to your research? What is ‘mitochondria drug discovery’?

I started my ‘love affair’ with mitochondria during my undergrad degree at Birmingham, particularly in my year in industry with AstraZeneca. Basically, mitochondria are organelles, small entities within our cells. Their main job is to make something called ATP, which is the energy our cells use. So, if something goes wrong or your mitochondria start to degrade, then that will reduce the amount of energy and your cells don’t work as well.

The lab I’m working in looks specifically at Parkinson’s disease. By looking at the mitochondria, we can try to find ways to improve their functionality. Can we stop them from degrading? Once they’ve started, can we stop them from getting worse?

Currently, I’m using genetic editing tool called CRISPR-Cas. It’s been in the news recently, you might have seen those stories about ‘designer babies’ and the like? But we use it as a research tool to see how removing genes from the genome affects mitochondria.

If we remove a gene and it improves function, then we could maybe use it as a treatment for Parkinson’s.

If removing a gene decreases function in healthy cells, then that tells us something else. Perhaps this is one of the ways that the disease itself progresses?

So, it ties into two aspects of research: one is treatment and the other is understanding.

How’s it been so far to use CRISPR-Cas and the general discourse around that?

It’s one of the most innovative areas at the moment. We’re seeing huge advances. Previously, we were only able to completely physically remove genes. Now, we can ‘silence’ genes by turning them off temporarily. This means we can do a kind of ‘before and after’; what happens when we turn the gene off? And what happens when we turn it back on again?

The technology is getting more specific and detailed all the time, too. I think it’s going to become a really huge therapeutic area in future.

For example, there are clinical trials being run into diseases like Sickle Cell. With diseases like that, where you have one specific gene that’s ‘switched wrongly’, you could eventually use it to just flip the switch the right way.

Meanwhile, for Parkinson’s, we’re using it more as a tool to look for helpful molecules for treatment.

Any thoughts on that wider discourse around gene editing?

In the research community, it is very much a tool for research and very specific treatments. That said, people will always use tools for things they aren’t designed for.

When I was at Newcastle, they were working on mitochondrial donation or ‘three parent baby’ research to treat mitochondria disease patients. It’s tightly regulated here. But in other places around the world, it’s being used to treat women with low fertility, or to treat other diseases.

Like any tool, you create it for the general good. Then you have to keep facing those ethical and moral issues in the future. I recently went to a conference in the US, which highlighted these issues. So that’s one way for the research community to ask important questions about guidelines and regulation.

To you, what’s the most exciting thing about the work you’re doing?

For me, it’s using CRISPR-Cas to really understand disease. There are still so many questions that need to be answered and these tools are advancing our understanding massively. Every other month there’s news about new genes and pathways.

And I think the work of the Oxford Parkinson’s Disease Centre (OPDC) is really important, especially because of its excellent collaboration with patients. We have a lot of cell lines available to us, and using these stem cells we can grow them to form neurons. Working on actual neuronal tissue makes a huge difference for modelling the complexity of the disease. Along with the new techniques of CRISPR, that puts the OPDC in a leading position world-wide.

What are the big benefits of patient involvement and contribution?

There’s a huge impact! One of the reasons a lot of companies like to work with research institutions in the UK is that our research is tied to institutions like the NHS. There’s a great referrals system to get patients together and get them organised. And the patients just really want to help us and to see progress in therapy development.

There’s fundraising too, not just for the big charities, but also from local patient groups. They have things like a pub quiz to help raise money so we can buy lab equipment.

They also donate stem cells, do clinical trials and make samples available to us, which helps with diagnosis. Their families offer support too! It’s an awful disease, but it’s a powerful community.

What are some things about working in research and science that surprised you or might surprise others?

The more you research something, the more questions arise. That surprises me.

I think there’s this perception of scientists as people who have all the answers, but actually we just have all the questions! It’s all about asking the right questions and finding out how to answer them, rather than finding the answers themselves.

You’ve worked in Newcastle, Birmingham, and now Oxford. What have been your favourite things about those places?

I’m originally from Kenya and when we first moved from there, we had family in Birmingham. So, I went to nursery in Birmingham and still have family there, so I’ve always had a soft spot for it. I’m a midlands girl at heart, and now I live in Leamington Spa (which is a much trendier place now than the small town I grew up in).

When I did my year in industry, I lived in Manchester. I loved the north! And I made great links with a community of scientists who were also on the placement programme with my at AstraZeneca.

Then I moved to Newcastle for my masters and PhD. It has a great quality of life; you’re near the coast, near 3 national parks, and you can walk everywhere. Plus great food and nightlife, so definitely a ‘work hard, play hard’ PhD. My PhD mentor was also very knowledgeable, he was a clinician neurologist, so he really drove home the patient focussed aspect of research.

Then I saw this post-doc in Oxford with Richard Wade-Martins. It was in the area of drug discovery, which is a great fit. Plus, it’s a great lab with amazing resources and research, and the people here push you to be at the forefront of new techniques. So, all of that drew me to Oxford. And then I arrived and thought ‘Oh, Oxford’s so nice!’

You mentioned your PhD mentor was a pretty big influence – were there any other people or events that inspired you and shaped your work?

My year in industry was also really formative, finding out what commercial research looks like. I also worked at the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland during my PhD, where my collaborator was keen to give me experience of all the different stuff going on there. Commercial science is very goal-oriented, so you get these huge institutions working together really well to get results to for compounds and allow products to be delivered to the market.

I’m beginning to explore the idea of business in my research too, like a start-up or spinout. Oxford is a great enterprising hub, with lots of support like Enterprising Oxford. I’m part of a cohort called RisingWISE, which helps 40 women from Oxford and Cambridge develop creative, innovative, enterprising skills. It’s also great for meeting women from industry, gaining mentorship and networking

I’ve recently also been accepted onto the Ideas 2 Impact programme at the Säid Business School. This initiative recruits Postdocs to join the Strategy and Innovation module of the MBA programme, giving Scientist and Executives the opportunity to work together on business ideas. I am really looking forward to starting this in January.

Any ideas sparked for a spinout already?

I’d love to have one, but not yet! At the moment for me, it’s about building that skillset and that mind-set to think about research in that commercial way. As a researcher we’re already analytical, and setting up research groups or labs is already a bit of an entrepreneurial prospect. But you also need to flex those creative muscles.

Are there any other difference between academia and industry, or things they can learn from each other, that it’s important to highlight?

I’ve always seemed to be part of collaborations between the two, which I think are becoming more and more normal. They have this really good balance between them. At the end of the day, industries are keen to make their bottom line, to find a compound or therapy that will cure a disease but also make a profit. Academia is more about the minutia, going back to basics and saying ‘okay, what does this protein do?’ rather than jumping to ‘what could it cure?’

And sometimes maybe academia gets a little stuck in its rut? It can be too focused and detailed-oriented, with researchers hidden away in our laboratories. And I think industry can sometimes be not detailed enough, as they’ve got deadlines and money and time constraints.

So these collaborations are a really good middle ground. They help researchers be part of something bigger and impact-focused, but gives industry the ability to really understand therapies. And this makes for better drugs!

Any other moments in your career you’re proud of and want to celebrate?

I think handing in my thesis for my PhD, probably! That was tough!

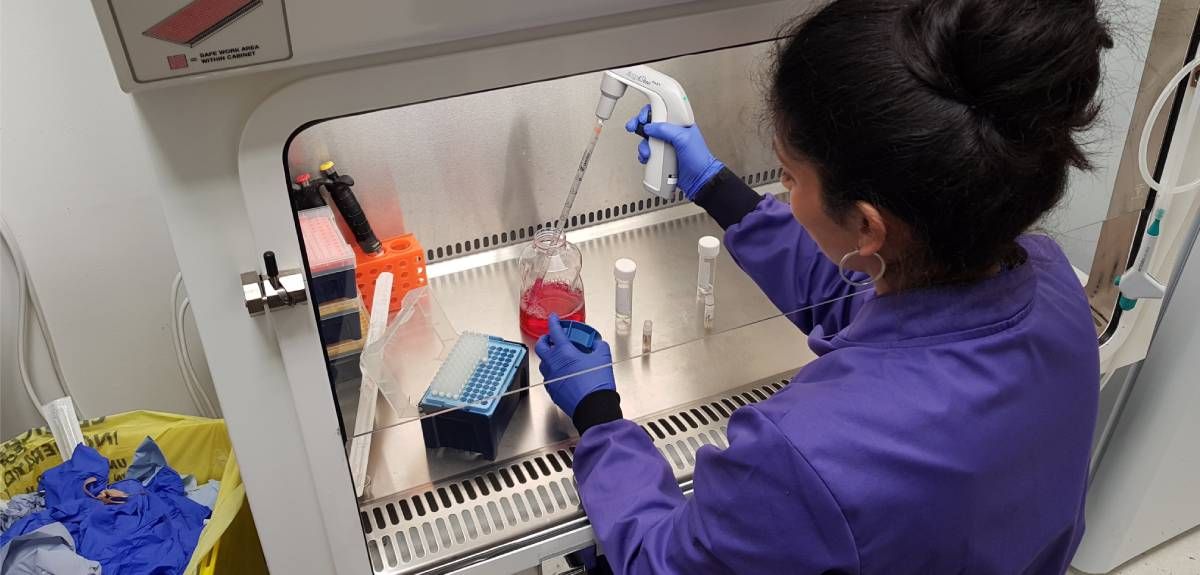

I have loads of small things I’m proud of – I’m proud of supervising students and seeing them flourish. I’ve supervised a lot of medics who’ve come in with no experience of holding a pipette, and by the end of things they were giving me ideas for their project and learning independently. So, I think training is a really important aspect of science as it can go both ways.

And being part of collaborations that have meaningful impacts on patients! Having a career with a cause is important to me.

Can I ask about experience of being a woman and minority in science? What would you like to see put into place to encourage people into STEM?

As a woman, it’s interesting! There’s lots of women in science, especially biology, but less in other STEM areas. Why do so many of us go into biology? I reckon that has something to do with how we’re raised.

I think it’s retention that really suffers, across all subjects. I’d like to see us asking questions like: where are people dropping off? When are they changing careers? What are the barriers making it difficult? Is it the temporary nature of academic contacts? Do we need to rethink how we deal with childcare and maternity leave?

Being a woman of colour (I hate that phrasing, by the way, but it’s how it’s said), you don’t have many role models; not a lot of professors look like you. There’s a community aspect too; where do you feel like you belong? I’ve been in several situations across various jobs where I’ve been the only woman and person of colour in the room. I never really thought to question it until recently.

I don’t think addressing that is a quota-filling task. I think it’s about going into communities and starting with the grassroots. Where are we employing people from? How do we expand to recruit from new communities, schools and universities across the country and world?

Also, I think unconscious bias has a huge part to play. In this country, it seems like some people think that when you don’t see overt racism, then it doesn’t exist. I think it’s more subtle and more nuanced, which makes it hard to challenge. We all have biases we don’t think about, so that kind of introspection is really important.

What is one really interesting thing that you’d like everyone to know?

I’d like people to know how close connections are related to healthy longevity.

Aside from exercise, good meaningful relationships are the best thing for long-term health. So go and make connections, volunteer, enjoy your hobbies and just make time to meet like-minded people. Friendship – it really is the key to a long and healthy life.

If you could work with any scientist, living or dead, who would you want to work with?

The scientist I would most loved to have met is Wangari Maathi. She was born in Kenya (as was I, so very close my heart) and after winning a scholarship to study biology in the US, she was the first woman in Central and East Africa to gain a doctorate. She recognized that deforestation was causing a decrease in biodiversity and food crops, affecting mainly women who are the resource gatherers in many African communities. She founded the Green Belt Movement which paid local women to plant trees. The Movement grew to encompass almost a million people and had major political ramifications in Kenya.

In 1990 she set up her own political party and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.

I think Dr Maathi’s ability to apply her science to a grass roots problem and make rapid impact in improving the lives of people in her community is incredibly aspiring. I would love to be able to do similar work in the future, using my background in biological research to bring about positive changes in healthcare for individuals.

You’ve also done some really interesting outreach work in the past, right? Can you tell me about that?

Yes, I have a longstanding interest in getting scientists out of their labs and involved in other areas and in communities.

In Newcastle, we had a collaboration with a Fine Art course, creating installations that drew on all kinds of science themes. We then went on to work with the National Trust’s Women in STEM project, with award-winning artist Olivia Turner. We created these amazing 6-foot wooden sculptures that are now on display in the Cheeseburn Sculpture Park.

I’m very keen to re-establish that kind of project in Oxford, too! I’m meeting and liaising with various groups, so watch this space.

Black female scientists have historically borne the brunt of both racial and gender biases in their fields, and in a white male dominated industry like the sciences, their achievements can at times go unsung.

These adverse circumstances make their victories all the more significant, and their contributions to the scientific community invaluable.

In celebration of Black History Month we are shining a light on some of the brilliant black minds of Oxford whose research is helping to improve the world today.

'I had never seen any prominent women of colour in zoology until I joined twitter'

Tanesha Allen, an African American Zoologist and behavioural ecologist at the Wildlife Research Conservation Unit (WildCRU), Oxford University, discusses her research studying the behaviours of European badgers, transatlantic culture shock and how and her experience as a black female scientist compares to others in her field.

Earlier this year Tanesha was awarded ‘Highly Commended’ at the Vice-Chancellor’s Public Engagement with Research Awards for her community outreach work, encouraging girls aged 11-14 to choose a career in science.

What is your research area?

I study olfactory communications in European badgers. That basically means understanding how these animals use scent to advertise themselves for mating opportunities. An animal’s scent can tell you a lot of information about them, from their age through to the group that they are from.

I started my DPhil at Oxford University in October 2016, and am I’m now in my fourth year of working with WildCRU and am part of the Wytham Woods Badger Project, which has been running since 1987.

Tanesha Allen, is a Zoologist and behavioural ecologist at the Wildlife Research Conservation Unit (WildCRU), Oxford University. Image credit: WildCRU

Tanesha Allen, is a Zoologist and behavioural ecologist at the Wildlife Research Conservation Unit (WildCRU), Oxford University. Image credit: WildCRUWytham Woods has the highest population of badgers in the world – 250 total, including 200 adults and 50 cubs. Each season we spend two weeks live tracking the badgers, using a unique tattoo which they have on their inner thigh. We use this to gather information on their weight, body condition, teeth, wounds and scars etc., to see how they change over time. It helps us to understand their movements, and how these animals respond to the challenges that they face, such as changing habitats, and how we can best protect them. Understanding their movements and behaviours can also help us to prevent the spread of tuberculosis (TB).

What is a badger fact that people would be surprised to know?

Badgers are naturally promiscuous, and mate with everyone. Females have something called superfetation, which allows them to mate with, and have their embryos fertilised by multiple males.

What is a typical day in the life like for you?

There is no such thing as an average day for me. My daily routine changes from season to season. During one season I could be spending all day in the woods collecting samples, at another time I’ll be releasing badgers back to their sets, and at others, I spend all day in my office reading journal articles. Another big part of my work is public engagement, so I spend a lot of time in schools with children running workshops to try and engage them with wildlife and conservation.

You were recently awarded “Highly Commended” at the Vice-Chancellor’s Public Engagement with Research Awards for your citizen science project with local schools. Firstly congratulations! Secondly, what interests you most about working with young people?

I love working with students, and how open they are to learning.

Usually in outreach with adults they often already have preconceived ideas about what science is and what they believe should be done, or shouldn’t be done. But with students they don’t have any preconceived notions. Just an eager thirst for knowledge.

Tanesha works with the Abingdon Science Partnership and Science Oxford on a project encouraging girls aged between the ages of 11 and 14 to choose careers in science.

Tanesha works with the Abingdon Science Partnership and Science Oxford on a project encouraging girls aged between the ages of 11 and 14 to choose careers in science.Can you tell us about your project?

I work with the Abingdon Science Partnership and Science Oxford on a project encouraging girls aged between the ages of 11 and 14 to choose careers in STEM, especially physics. I volunteered initially, and over time have got more and more involved in science outreach and communications.

Our work is funded by the Royal Society Partnership Grant, and we work with local secondary and primary schools, teaching students how to use camera traps to monitor wildlife, analyse footage and also animal behaviour. The project has been running for just over a year.

I’m also teaching them how badgers react to scent from different species and have taken them out badger tracking. We have found nine badges and six cubs so far.

Image credit: Tanesha Allen

Image credit: Tanesha AllenTanesha's research focuses on factory communications in European badgers and understanding how they use scent to advertise themselves for mating opportunities.

Did anyone ever try to discourage you from pursuing a career in science?

The opposite actually, I never encountered any push-back, I was always an academic person who got good grades at school, so people were very encouraging to me.

I did encounter some challenges during my Undergraduate Degree at Washington State University. I think that was when I became more aware of social issues such as, racism and sexism and how they affect me. I went to a very diverse elementary school, and then moved to the suburbs, which were not as diverse, but I was definitely sheltered from some harsh realities like that.

Can you elaborate?

I became more aware of what it meant to be a black woman in society when I went to university.

When I started my degree I became more aware of what microaggressions were, and how people from marginalised groups are treated compared to more privileged groups.

I was one of two black women on an animal sciences course, surrounded by a lot of white students and professors, and I became aware of a number of microaggressions. There was always an assumption I was lazy or unmotivated. It was very hard and it really got to me.

Mostly because I had not encountered anything like that before in my life.

How did this experience affect you, and how did you learn to overcome it?

It was hard, and is something that I still wrestle with now. But I have learned to focus on what I bring to the table. I know my worth and the value of my research. I won’t allow someone to make me feel that way again – but it is not easy.

As a black female zoologist what does Black History Month mean to you?

In my opinion, Black History Month is an important time for everyone - regardless of their race - because, black history is a part of history. Period. Both in the US and UK, black people have had a huge impact on the development of these countries and certain social movements have influenced the trajectory of those countries, in ways that influence society at large, not just one group of people.

Black History Month is an opportunity to highlight the achievements that the black community has made in spite of the obstacles put in our way, while highlighting that more needs to be done – especially somewhere like Oxford.

On a personal level I enjoy hearing other people’s stories and connecting with others in the field. I had never seen any prominent women of colour in zoology until I joined twitter last year. But being active on social media has allowed me to connect with other women of colour in the field who share my passion for zoology, and to celebrate them more.

What is it like to work side by side a conservation icon like Professor David Macdonald?

It is amazing working with David. The year before I applied to Oxford University, Cecil the lion died and it was major news everywhere, including America, where I am from.

What gets you out of bed in the morning?

I enjoy mastering a puzzle, and putting the pieces together of figuring out how animals communicate with each other. What affects their interactions with each other, their environment and with us? I want to know how we can use their behaviour to help improve the environment.

Have you always had an interest in conservation and wildlife?

I was always interested in science as a child.

I was born and raised in Tacoma, Washington, USA, and remember going outside a lot, and spending time in my apartment complex. I loved playing with bugs and watching my neighbours dogs and birds. But, the only jobs I knew of that involved working with animals were being a vet or a zookeeper. I didn’t have much knowledge of other animal related jobs.

Animal behaviour in general has always fascinated me, particularly how similarities to humans and how they choose mates. A lot goes into that decision – who you have already mated with, who you are related to. Humans do the same thing.

How did you find moving from the US to the UK for your graduate studies and PhD work, was it hard to adjust to a new environment?

I’ve been in the UK since 2012, and the transition from my education in America, to here, has been interesting. The main thing for me was adjusting to cultural differences. Americans are more outgoing and forthright. I find it can be hard to know if you have offended a Brit, because they don’t often tell you directly.

Was your experience as a black women in science different in the UK to your American university?

There were good and bad elements to both experiences, and I have experienced discrimination in both countries in different ways.

What do you think needs to change to eliminate these behaviours?

We tend to talk a lot about sexism in STEM, but there is not a lot of talk about how different women from different types of backgrounds encounter different challenges in STEM. So there is not a lot of focus on intersectionality. I think one good step would be addressing unconscious bias. As scientists we are trained to be objective and logical. Often there are times we think we don’t have unconscious biases with social issues, or towards certain groups of people, but we do. I think having our unconscious biases addressed, and unlearning our own behaviours would be a good way to make things easier for the next generation of women and women of colour in

STEM.

Image Credit: WildCRU

Image Credit: WildCRUTanesha and her team in Wytham Woods

During my second and third year at Oxford I was the postgraduate representative for the Oxford University Campaign for Racial Awareness and Equality, which allowed me to push forward ideas around conducting racial awareness workshops on a college and department level. Postgraduate students are more connected to their departments than their colleges so it is important to consider both areas.

Is there anything that you would change about the University?

There is a lot I would change about how marginalised, and under-represented groups are treated in Oxford.

There are definitely more initiatives in place that are helping to improve diversity, and encourage more people of ethnic minorities to apply, which is excellent. However, the next step is making sure people from these groups are included more within research grounds, colleges and wider projects.

It is one thing for institutions to be diverse, but if those people don’t feel like they are being properly valued, included and respected, these initiatives fall short.

What’s next for you when you finish at Oxford?

I am finishing my thesis and will complete my PhD next summer. I am not sure what comes next, but I hope to continue my science outreach work with children, and would love to stay in the UK.

What do you like most about being part of Oxford University?

To me the history behind it is incredible. Whenever you walk around, the tiniest things are connected to a prominent person who made a historic contribution to the University centuries ago.

Compared to the States the oldest buildings and things would be from at most the 1700s. Whenever I walk around central Oxford, and look up and see the beautiful Bodleian Libraries and Sheldonian Theatre around me it can be me it is surreal. Especially when I see the tourists walking around, taking pictures and looking in awe just to be here, it reminds me how lucky I am, and I think to myself ‘I actually live here, that’s cool!’

How do badgers respond to scents from other species?

‘I’m passionate about what I do’ is arguably one of the most hollow, overused expressions in the CV writing handbook. For an increasing amount of people who clock-watch their way through a 9-5 existence, rarely getting the results or satisfaction that they are hoping for, having a passion for your work is more of a pipe dream than a tangible reality. Particularly for those further along the career path, who often convince themselves that they are either too old to succeed or that it is too late to try.

For the first 15 years of her professional life, Carlyn Samuel was one of these people. Having built a successful PR career, it was only when she put the brakes on and took some time for herself, that, at the age of 38, she made the decision to take a Master’s degree in Conservation Science and start over. Eight years later, she has never looked back and is now a research coordinator at Oxford’s Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science (ICCS). She talks to ScienceBlog about why making a major career transition later in life was the best decision she ever made, and how she has used her communications expertise to make research more accessible to the wider public through Soapbox Science.

What triggered your decision to change career?

I spent 15 years of my working life in PR for the printing industry – not exactly the most eco-friendly world. The lack of fulfilment bothered me, but never enough to actually do anything about it. A three month sabbatical exploring the Amazon Rainforest turned out to be life-changing. Few people know this, but substantive parts of the Amazon are owned by the fuel industry. In one area I visited it shocked me to see the region divided up into plots. Instead of town names each bore the name of a multinational oil company. But I came across one community that was completely independent. Despite extreme pressure they had refused to sell out to big business, and they had started an eco-lodge. It struck me that if they could stand up and save their little piece of the jungle, I could do my part to protect our wonderful planet.

So, at 38 I decided to go for it, and applied for a master’s degree in Conservation Science at Imperial College London, which is where I met EJ Miller-Gulland, (Tasso Laventis Professor of Biodiversity in Oxford’s Department of Zoology.) She offered me a job after I graduated and I have been working for her ever since.

What does your role in the ICCS group involve?

I’m lucky that I get to work on a number of different projects in one job. From trying to change the discourse in conservation through our Conservation Optimism movement, to protecting endangered antelopes with the Saiga Conservation Alliance. This involves travelling to central Asia a lot and working with rural, low income communities. Most have challenging lifestyles, with temperatures ranging from 40 degrees celsius in the summer to -30 in the winters, often with no running water and limited electricity. It reminds me to count my blessings and appreciate how lucky I am to live where I live, and be able to help people and biodiversity in some small way.

What do you enjoy most about conservation research?

I love the multi-dimensional nature of our work. Conservation isn’t just about saving specific species, it is about understanding the whole eco-system, the importance it has to local communities on many different levels - be it cultural, spiritual or economic - and the demands being placed on it by different stakeholders. Then understanding how to best work with people most affected by any conservation decision, as well as other groups and experts to safeguard both that biodiversity and people’s wellbeing.

The ICCS runs a number of projects including the Saiga Conservation Alliance, protecting the endangered antelopes of Central Asia and the former Soviet Union. Image credit: Shutterstock

The ICCS runs a number of projects including the Saiga Conservation Alliance, protecting the endangered antelopes of Central Asia and the former Soviet Union. Image credit: Shutterstock

How do you go about this?

A successful project often considers the big picture, so is tackled by an interdisciplinary team.

One ICCS project involves tackling the illegal wildlife trade, bringing together inspirational colleagues across the University that you wouldn’t normally interact with. For example, we are working with the Oxford Internet Institute to understand the trade’s digital footprint and the role of the dark web. To address the problem we’re utilising theory and methods from public health, economics, psychology, ecology and sociology. I never would have imagined that a career in conservation would involve so many different skill sets.

Have there been any stand-out highlights for you so far?

The Conservation Optimism movement is brilliant. Thanks to things like Blue Planet, ocean conservation is an issue that seems to have finally captured public attention. The summit I helped to arrange last year brought people of different ages and backgrounds together, from all around the world.

Young people are so internet savvy and enthusiastic, it was really inspiring to sit and listen to what they are doing to conserve nature. They are able to tap into so many new funding streams because people want to support local, youth-driven programmes. We had conservationists with over 40 years’ experience eagerly engaging with the next generation of conservationists, wanting to learn from them and vice versa. It was great see that knowledge exchange in action. When we set up the initiative we wanted to create a hub for people to share ideas and connect with each other, which is really taking off. And now there are smaller Conservation Optimism events springing up across the world as a result.

What are the biggest challenges in your work?

It can be hard to get funding for conservation if the project doesn’t involve charismatic megafauna in Africa – and particularly if you work in ex-Soviet countries, as we do. For us, £5k is a tonne of money that we can do so much with. We can run a saiga awareness programme across multiple schools, in several countries! Or fund a womens’ embroidery initiative in Uzbekistan to empower women.

Publicity definitely helps though - recent coverage around saiga deaths has triggered a peak in interest in conservation-related issues. We are getting there, we just have to sustain that momentum.

What has your experience been as a women starting a career in science later in life?

Coming in at Master’s degree level there were more women on my course than men, which was a welcome surprise, and we’ve continued to support each other’s careers ever since. I have been fortunate to have strong female role models and mentors like EJ, so have never felt unsupported. For me the challenge was learning how to study after all this time, and learning my way around a new field.

For various reasons it is difficult to get women to consider taking-up scientific careers. I looked into this a little more and discovered that at school, girls are more likely to rate science as their favourite subject, and out-perform boys at GCSE, A-level and degree-level. Even so, STEMM subjects have been found to account for only 35% of the HE qualifications achieved by women. Notably, women account for only 15% of UK science professors and are woefully underrepresented when it comes to key positions within STEMM-based careers in the UK.

I think there is a constant bias, particularly for women who return to work after having children. Unconscious questions like ‘is she still going to be as focused on her work?’ Men who become fathers are rarely judged in this way.

The way the media biases perceptions does nothing to help change the dialogue. Headlines about ‘female pilots/doctors/scientists’ drive me mad. She’s not a female pilot, she’s a pilot.

Carlyn also works on Conservation Optimism, the global initiative dedicated to sharing optimistic stories about conservation and inspiring people all over the world to do their part to protect the planet.

Image credit: Shutterstock

Carlyn also works on Conservation Optimism, the global initiative dedicated to sharing optimistic stories about conservation and inspiring people all over the world to do their part to protect the planet.

Image credit: ShutterstockHow did you come to be involved in Soapbox Science?

I stumbled across it in London and just thought it was such a great way of getting science out there and showing people that women in science are not freaks – they’re real people who can be very approachable.

It works on different levels, first to get young women more engaged in science, and secondly, to challenge our academics to communicate their research in a more accessible way, it also does a great job of boosting their profiles and careers.

Young girls who might be passing and have never thought of science as an option for them get to see how fun it can be - it’s not just about the highbrow science. We have had a few situations where children have approached the speakers afterwards to thank them for being so brave and inspiring. If you just inspire one person, that’s all it takes.

What do you like most about the initiative?

There are so many incredible women here but trying to get them not only to talk about their work, but to a general audience, can be a challenge. They are so nervous, but once they get up on the soapbox they are running on adrenalin. It isn’t just good for their science but for their CV and their confidence. It can lead to jobs in science communications and increased research funding. I love seeing them excel.

What do you think can be done to encourage more young people to get into science?

School curriculums need to make the real world connections clearer to make learning more interesting and relevant.

It’s often said that if you are bad at maths or science you can’t work in a science-led field, but I don’t agree. You can still offer a lot, but there needs to be a route in for these people too. We need to teach young women that you don’t necessarily have to be a scientist to work in ‘traditional’ scientific environments. I recently spoke with a fantastic drone pilot working on a rigorously scientific ocean conservation project. She isn’t a scientist but the project would have been impossible without her.

What are you looking forward to this year?

I run our biodiversity fellowship programme, which is a great two-way learning experience. It allows three people a year to come and work with ICCS for a term, fully funded. When the programme first launched we had about 50 applicants but now it is so popular, that we have over 300.

We recently had a vet with us from Uganda who works on gorilla conservation. She noticed that local people, with limited access to basic health and other social services were passing diseases to the gorillas, so she developed a public health programme. Integrating human, animal and ecosystem health together is a new field in conservation and gaining traction. Coming into the office is like getting my batteries recharged with inspiration.

HIGHLIGHTS FROM SOAPBOX SCIENCE OXFORD 2017:

It’s no secret that of all the STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) specialisms, the engineering industry has the biggest diversity problem. Just nine per cent of the UK’s engineers are female, and a disappointing six per cent of those in professional engineering roles are from black and minority ethnic backgrounds.

But, as followers of this series may have noticed, thanks to the combined impact of increased campaign efforts encouraging more women and minorities to enter the field, and the heightened visibility of established female mentors, the scientific community is evolving.

As a Canadian woman of South Asian heritage, Dr Priyanka Dhopade, Senior Research Associate at Oxford University’s Department of Engineering, notes female mentorship as a key factor in both the diversity tide turning, and her own career progression, commenting; ‘Female role models play a big part in a young girl’s life, and whether she can see herself in a certain role. From one of my earliest role models, Roberta Bondar, the first Canadian woman in space, to Professor Alison Noble, an incredible Biomedical engineer, they have been a motivating force in my career. You see someone like you, and just think ‘if she can do it, so can I.’ I want to offer that mentorship to other women and young girls.’

Dr Priyanka Dhopade was just named one of the UK's top 50 female engineers under 35, by the Women's Engineering Society.

Dr Priyanka Dhopade was just named one of the UK's top 50 female engineers under 35, by the Women's Engineering Society.In this spirit, Dr Dhopade, who was chosen by the Women’s Engineering Society, as one of 2017’s top 50 women in engineering under 35, recently organised a community outreach event to celebrate the International Women in Engineering Day (23rd June). During the event, young female science lovers, from across the county, (aged 13-15), had the opportunity to meet and learn from established industry leaders, over afternoon tea. Some attendees talk to Scienceblog about their experience of the day, and why female mentorship is so important to them.

Professor Alison Noble gives a motivating speech at the National Women in Engineering Day Afternoon Tea.

Image credit: Janet Hovard

Professor Alison Noble gives a motivating speech at the National Women in Engineering Day Afternoon Tea.

Image credit: Janet HovardProfessor Alison Noble OBE FREng FRS, the event’s key note speaker, is a Professor of Biomedical Engineering and a co-founder of the medtech spin-out company; Intelligent Ultrasound Ltd. She discusses the vital role of engineers in society and her own personal journey towards being a successful engineer.

How would you describe your work to someone who knows nothing about engineering?

I am a senior academic engineer specialising in ultrasound image analysis, and I split my time between running a large biomedical engineering research group and raising funds for its activities. I also teach at the University, and I am Chief Technology Officer of my spin-out company, supporting the development of its products. I sit on a number of national committees that promote engineering in healthcare, and the commercialisation of science inventions and the growth of small science-based companies.

How has the industry changed during your career?

Image analysis deals with the extraction of meaningful information from ultrasound scans. When I started working in the field about 20 years ago, the academic and commercial focus was on imaging physics and improving image resolution, so that clinicians could see smaller structures and assess organ function. At that time, image analysis was considered a nice add-on, but not seen as having great commercial value. But, now the roles have in many ways reversed, or at least re-balanced. This is largely thanks to image digitisation, and more recently, the availability of large datasets, combined with advances in machine learning algorithms - particularly deep learning. Now, the focus is on how image analysis can be used to support workflow improvements and automatic diagnosis. My field has in a sense come of age, so there are exciting times ahead.

What research achievement are you most proud of?

At every career step there can be something special. For me, now, it has to be my recent election as a Fellow of the Royal Society. It is an incredible honour to receive such prestigious recognition.

What is the biggest challenge you face in your work?

Managing the many responsibilities, requests and expectations of an academic today.

What are your goals for the future?

My advanced European Research Council award is an ambitious project aiming to develop a next generation ultrasound imaging device, which is easier for a non-expert or occasional user to operate, than current systems. It uses machine learning to understand how an expert scans, and to build this knowledge into the ultrasound device. Realisation of this could have a big impact on use of ultrasound in healthcare.

We are also starting new collaborations in the developing world, specifically in Kenya and India. Unlike in the western world, women often do not go for antenatal check-ups during pregnancy. They only seek professional medical help if they feel very unwell. Working with overseas partners will help us to develop and evaluate imaging solutions that meet the unmet clinical need in these countries and could improve pregnancy risk assessment and outcomes in these challenging environments.

Are there any unique challenges to being a woman in engineering?

Two challenges come to mind, firstly, and perhaps surprisingly, as part of the movement to address gender im-balance in engineering, there are now arguably more opportunities presented to women to advance their career than men. But, this also means that women can be over-burdened with requests on their time, so individuals have to try to find a balance that works for them.

Secondly, the number of female directors, or members of senior management teams in companies - especially small ones, is depressingly low. I would like to see more women encouraged to get involved in innovation and set-up their own companies.

What more can be done to address the gender im-balance in engineering?

As with getting women into science, it all starts with school education. We need to teach school children to think creatively and to develop non-academic skills, which might inspire them to consider working in companies, and even setting up their own companies. Universities also need to take entrepreneurship education more seriously as core business.

Image credit: Jane Hovard

Image credit: Jane Hovard Why do you think events like today’s International Women in Engineering outreach tea are so important?

Special interest meetings are really important and bring together people with a common interest. For some attendees, they provide an opportunity to network and share experiences. For others, attending a meeting of this kind can potentially change their life.

Gladys Ngetich, Rhodes Scholar, Aerospace Engineering Dphil Student, Department of Engineering, Oxford University

What is your research area?

My research involves developing advanced and more efficient cooling technologies for jet engines. We work in a close partnership with Rolls-Royce Plc and are trying to find a new method of cooling that will use as little air as possible. The principle being that, by improving the overall engine efficiency you reduce emissions.

Gladys Ngetich, Rhodes Scholar, Aerospace Engineering Dphil Student, Department of Engineering, Oxford University

Gladys Ngetich, Rhodes Scholar, Aerospace Engineering Dphil Student, Department of Engineering, Oxford University

Did you always want to be an engineer?

Yes! My passion for engineering started when I was at secondary school in Kenya, where I grew up, but I always loved maths and science. My father and two of my brothers are engineers, so it was always a hot topic of conversation at our house.

What is the biggest challenge that you face in your field?

You need persistence and a lot of patience to be an engineer. Sometimes you have an idea that you think is great, but when you run the computer simulation to test it, it fails, so you have to start all over again. It can be a very long process that requires a lot of patience.

What are your goals long term?

I just want to be useful. Providing engineering solutions to all sorts of real world problems.

Are there any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

There is definitely a difference between being a man or a woman in engineering, and not just at Oxford. Even during my Undergraduate degree in Kenya, in a class of 80, I was one of eight women - that’s a ratio of one to ten.

Whether because of gender, or skin colour, when you are a minority it can be really lonely and challenging. You feel awkward, and it becomes about proving yourself. Proving to yourself and your classmates that you have as much right to be there as they do. At least half of the women in my class graduated with a distinction. It’s the same at Oxford, in a lab of about 30 DPhil students, I am one of three women, and one of two black students, so it’s a double challenge.

How can events like this support change in the industry?

I think there are lots of solutions, but for me, it is about encouraging young girls and talking to them from a young age about the importance of female role models and following your dreams. We have to really put the effort into supporting them to take STEM related subjects.

Some of the girls here today perhaps have never thought about a career in engineering, but after hearing Alison or some of the other speakers, they will start seeing it as a real possibility.

Never seeing someone that looks like you, working in the field that you dream of, can create a feeling that it’s not for you. Just being able to talk to, and even just see female and minority engineers makes all the difference.

Dr. Ana Namburete, Royal Academy Engineering (RAEng) Research Fellow, Department of Engineering

Dr. Ana Namburete, Royal Academy Engineering (RAEng) Research Fellow, Department of Engineering Dr. Ana Namburete, Royal Academy Engineering (RAEng) Research Fellow, Department of Engineering

Did you always know you wanted to be an engineer?

I actually grew up thinking that I was going to be the first doctor in my family. I am from Mozambique, and my parents’ generation were the first to be able to choose their own career after Colonial Independence. My grandfather had always wanted to become a doctor, but not had that choice open to him. He spotted my passion for biology and helping people, and urged me to become a doctor.

I was focused on that goal at school, but during my gap year I volunteered at a clinic, where I realised that the lifestyle of a doctor did not actually suit me. There were new machines coming in all the time, but nobody spoke English well enough to translate the manuals. I speak fluent English and Portuguese, so I took on that role. While I was setting up the machines, I realised how much I liked the technical side of understanding how machines work. That was when I decided that I wanted to be an engineer.

I had already applied to university medical programmes. But, I was lucky, I was accepted into Simon Fraser University, a liberal arts university in Canada, where I could change my degree. I switched to the Biomedical Engineering course, and have never looked back.

What motivates you?

I recently won a Research Fellowship with the Royal Academy of Engineering to look at how we can automate fetal ultrasound images. Most of the structural development of the brain happens during pregnancy so there is big potential for impact. I created algorithms that can learn the normal pattern of prenatal brain development, detecting abnormal development in the process. Because ideally, if you can detect abnormalities early, you have the opportunity to intervene.

Ultrasound is portable and affordable, so useful for community services. If we automate the analysis, diagnosis and detection of brain structures, then community health workers can operate the machine and collect the images. Our algorithms do the hard work so they do not have to.

What do you like most about being an engineer?

I love being able to work with different people, understanding and translating their needs, into solutions. I also get to travel lots – Malawi, most recently. I visited clinics to assess their ultrasound needs and work out plausible interventions that we could provide for them.

Are there any unique challenges to being a woman in engineering?

Well, there are not very many of us, and that’s a problem. When I did my undergraduate degree, there were 20 women out of 400 students in the entire engineering department. A really bad ratio - and I was the only black woman in the program. I couldn’t help but feel different.

Inclusion is a real issue. But, that being said, I have rarely felt that doors are closed to me - particularly at Oxford, where I have always felt supported. My chances of winning my Fellowship were actually increased by having the support of the department, and Professor Noble my as my mentor and role model.

What needs to change to level the engineering playing field?

I think we need to see more role models, and for that, we need more women in the industry in general. Girls decide at a young age whether STEM is not for them, and we need to understand why that is.

The way we interact with technology in general today is completely different to when I was a teenager. Now everyone is a digital native, interacting with smart phoned and the web from a young age. This is good news for STEM.

The girls' get hands-on, building a wind turbine.

The girls' get hands-on, building a wind turbine.

And what do the scientists of tomorrow think?

Mary Lee, 14 and Kitty Joyce, 15, Oxford High School, Oxford

‘We have really enjoyed this event and having the chance to decide what we want to do. We know that there are more men in science than there are women, but would never let this hold us back. Girls should be encouraged to do what they want, and women should have the same opportunities as men.

It has been great to meet new people, and take part in the practical workshop (led by Gabby Bouchard, Outreach Officer at the Department of Engineering). It was fun building the wind turbine.

‘We don’t learn about engineering at school and we should. We are here because we love science, but until today had never really thought about engineering as a job - but, that could change now.’

Sol Zee, 13 and Carys-Anne,14, Cherwell School, Oxford

‘It has been great to meet so many new people, and talk to other girls that love science too. We have a female science teacher, but listening to, and hearing how much the women here have achieved is really inspiring. It makes you excited that if you work hard, that could be you one day. We noticed that there are so many jobs in engineering that we did not know anything about, and will ask more questions about now.’

- 1 of 4

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria