Research spotlight: how our genes can help us understand disease

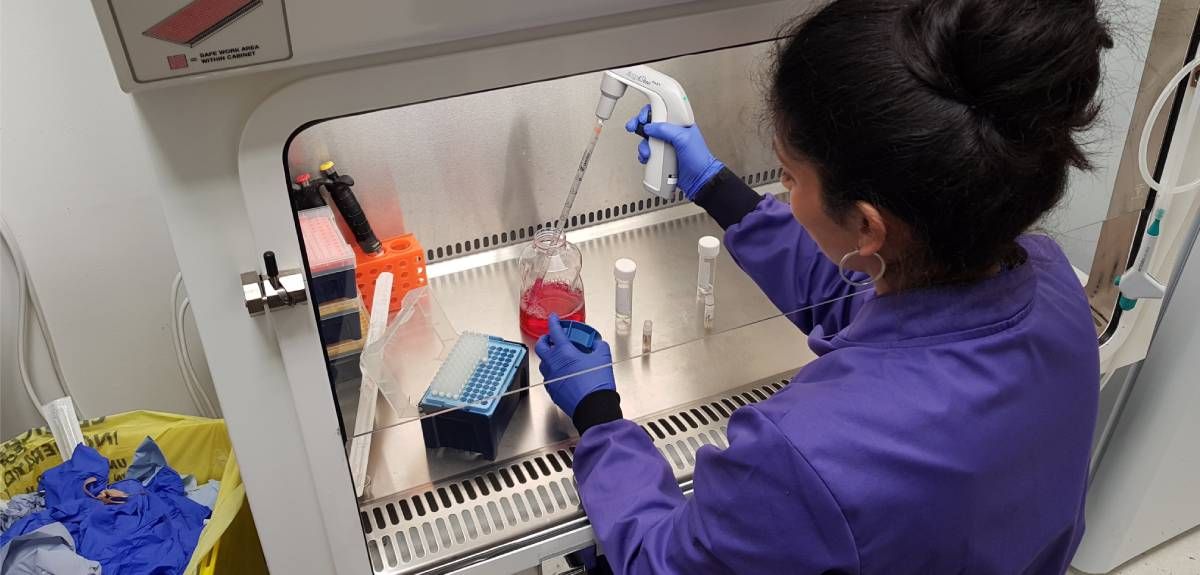

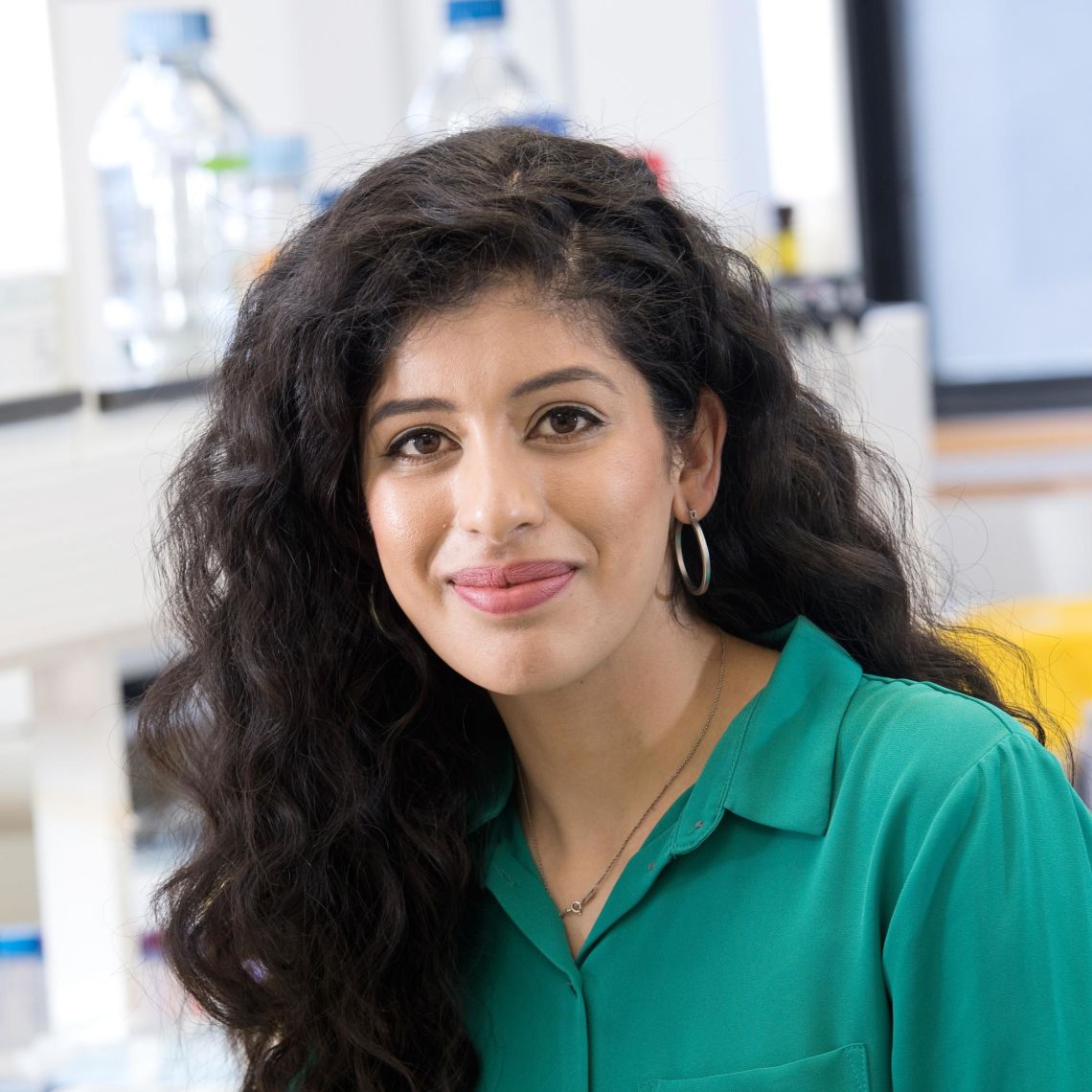

The latest in our ScienceBlog series of 'amazing people at Oxford you should know about' is Dr Pavandeep Rai. A Post-doctoral Research Scientist in the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, her work focuses on the effect of something called 'mitochondria' on Parkinson's disease, using cutting edge gene-editing cool CRISPR-Cas. Here she guides us through her career and experiences of pushing the boundaries of science in both research and art...

To start with, can you give us a beginner’s guide to your research? What is ‘mitochondria drug discovery’?

I started my ‘love affair’ with mitochondria during my undergrad degree at Birmingham, particularly in my year in industry with AstraZeneca. Basically, mitochondria are organelles, small entities within our cells. Their main job is to make something called ATP, which is the energy our cells use. So, if something goes wrong or your mitochondria start to degrade, then that will reduce the amount of energy and your cells don’t work as well.

The lab I’m working in looks specifically at Parkinson’s disease. By looking at the mitochondria, we can try to find ways to improve their functionality. Can we stop them from degrading? Once they’ve started, can we stop them from getting worse?

Currently, I’m using genetic editing tool called CRISPR-Cas. It’s been in the news recently, you might have seen those stories about ‘designer babies’ and the like? But we use it as a research tool to see how removing genes from the genome affects mitochondria.

If we remove a gene and it improves function, then we could maybe use it as a treatment for Parkinson’s.

If removing a gene decreases function in healthy cells, then that tells us something else. Perhaps this is one of the ways that the disease itself progresses?

So, it ties into two aspects of research: one is treatment and the other is understanding.

How’s it been so far to use CRISPR-Cas and the general discourse around that?

It’s one of the most innovative areas at the moment. We’re seeing huge advances. Previously, we were only able to completely physically remove genes. Now, we can ‘silence’ genes by turning them off temporarily. This means we can do a kind of ‘before and after’; what happens when we turn the gene off? And what happens when we turn it back on again?

The technology is getting more specific and detailed all the time, too. I think it’s going to become a really huge therapeutic area in future.

For example, there are clinical trials being run into diseases like Sickle Cell. With diseases like that, where you have one specific gene that’s ‘switched wrongly’, you could eventually use it to just flip the switch the right way.

Meanwhile, for Parkinson’s, we’re using it more as a tool to look for helpful molecules for treatment.

Any thoughts on that wider discourse around gene editing?

In the research community, it is very much a tool for research and very specific treatments. That said, people will always use tools for things they aren’t designed for.

When I was at Newcastle, they were working on mitochondrial donation or ‘three parent baby’ research to treat mitochondria disease patients. It’s tightly regulated here. But in other places around the world, it’s being used to treat women with low fertility, or to treat other diseases.

Like any tool, you create it for the general good. Then you have to keep facing those ethical and moral issues in the future. I recently went to a conference in the US, which highlighted these issues. So that’s one way for the research community to ask important questions about guidelines and regulation.

To you, what’s the most exciting thing about the work you’re doing?

For me, it’s using CRISPR-Cas to really understand disease. There are still so many questions that need to be answered and these tools are advancing our understanding massively. Every other month there’s news about new genes and pathways.

And I think the work of the Oxford Parkinson’s Disease Centre (OPDC) is really important, especially because of its excellent collaboration with patients. We have a lot of cell lines available to us, and using these stem cells we can grow them to form neurons. Working on actual neuronal tissue makes a huge difference for modelling the complexity of the disease. Along with the new techniques of CRISPR, that puts the OPDC in a leading position world-wide.

What are the big benefits of patient involvement and contribution?

There’s a huge impact! One of the reasons a lot of companies like to work with research institutions in the UK is that our research is tied to institutions like the NHS. There’s a great referrals system to get patients together and get them organised. And the patients just really want to help us and to see progress in therapy development.

There’s fundraising too, not just for the big charities, but also from local patient groups. They have things like a pub quiz to help raise money so we can buy lab equipment.

They also donate stem cells, do clinical trials and make samples available to us, which helps with diagnosis. Their families offer support too! It’s an awful disease, but it’s a powerful community.

What are some things about working in research and science that surprised you or might surprise others?

The more you research something, the more questions arise. That surprises me.

I think there’s this perception of scientists as people who have all the answers, but actually we just have all the questions! It’s all about asking the right questions and finding out how to answer them, rather than finding the answers themselves.

You’ve worked in Newcastle, Birmingham, and now Oxford. What have been your favourite things about those places?

I’m originally from Kenya and when we first moved from there, we had family in Birmingham. So, I went to nursery in Birmingham and still have family there, so I’ve always had a soft spot for it. I’m a midlands girl at heart, and now I live in Leamington Spa (which is a much trendier place now than the small town I grew up in).

When I did my year in industry, I lived in Manchester. I loved the north! And I made great links with a community of scientists who were also on the placement programme with my at AstraZeneca.

Then I moved to Newcastle for my masters and PhD. It has a great quality of life; you’re near the coast, near 3 national parks, and you can walk everywhere. Plus great food and nightlife, so definitely a ‘work hard, play hard’ PhD. My PhD mentor was also very knowledgeable, he was a clinician neurologist, so he really drove home the patient focussed aspect of research.

Then I saw this post-doc in Oxford with Richard Wade-Martins. It was in the area of drug discovery, which is a great fit. Plus, it’s a great lab with amazing resources and research, and the people here push you to be at the forefront of new techniques. So, all of that drew me to Oxford. And then I arrived and thought ‘Oh, Oxford’s so nice!’

You mentioned your PhD mentor was a pretty big influence – were there any other people or events that inspired you and shaped your work?

My year in industry was also really formative, finding out what commercial research looks like. I also worked at the Novartis Institute of Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland during my PhD, where my collaborator was keen to give me experience of all the different stuff going on there. Commercial science is very goal-oriented, so you get these huge institutions working together really well to get results to for compounds and allow products to be delivered to the market.

I’m beginning to explore the idea of business in my research too, like a start-up or spinout. Oxford is a great enterprising hub, with lots of support like Enterprising Oxford. I’m part of a cohort called RisingWISE, which helps 40 women from Oxford and Cambridge develop creative, innovative, enterprising skills. It’s also great for meeting women from industry, gaining mentorship and networking

I’ve recently also been accepted onto the Ideas 2 Impact programme at the Säid Business School. This initiative recruits Postdocs to join the Strategy and Innovation module of the MBA programme, giving Scientist and Executives the opportunity to work together on business ideas. I am really looking forward to starting this in January.

Any ideas sparked for a spinout already?

I’d love to have one, but not yet! At the moment for me, it’s about building that skillset and that mind-set to think about research in that commercial way. As a researcher we’re already analytical, and setting up research groups or labs is already a bit of an entrepreneurial prospect. But you also need to flex those creative muscles.

Are there any other difference between academia and industry, or things they can learn from each other, that it’s important to highlight?

I’ve always seemed to be part of collaborations between the two, which I think are becoming more and more normal. They have this really good balance between them. At the end of the day, industries are keen to make their bottom line, to find a compound or therapy that will cure a disease but also make a profit. Academia is more about the minutia, going back to basics and saying ‘okay, what does this protein do?’ rather than jumping to ‘what could it cure?’

And sometimes maybe academia gets a little stuck in its rut? It can be too focused and detailed-oriented, with researchers hidden away in our laboratories. And I think industry can sometimes be not detailed enough, as they’ve got deadlines and money and time constraints.

So these collaborations are a really good middle ground. They help researchers be part of something bigger and impact-focused, but gives industry the ability to really understand therapies. And this makes for better drugs!

Any other moments in your career you’re proud of and want to celebrate?

I think handing in my thesis for my PhD, probably! That was tough!

I have loads of small things I’m proud of – I’m proud of supervising students and seeing them flourish. I’ve supervised a lot of medics who’ve come in with no experience of holding a pipette, and by the end of things they were giving me ideas for their project and learning independently. So, I think training is a really important aspect of science as it can go both ways.

And being part of collaborations that have meaningful impacts on patients! Having a career with a cause is important to me.

Can I ask about experience of being a woman and minority in science? What would you like to see put into place to encourage people into STEM?

As a woman, it’s interesting! There’s lots of women in science, especially biology, but less in other STEM areas. Why do so many of us go into biology? I reckon that has something to do with how we’re raised.

I think it’s retention that really suffers, across all subjects. I’d like to see us asking questions like: where are people dropping off? When are they changing careers? What are the barriers making it difficult? Is it the temporary nature of academic contacts? Do we need to rethink how we deal with childcare and maternity leave?

Being a woman of colour (I hate that phrasing, by the way, but it’s how it’s said), you don’t have many role models; not a lot of professors look like you. There’s a community aspect too; where do you feel like you belong? I’ve been in several situations across various jobs where I’ve been the only woman and person of colour in the room. I never really thought to question it until recently.

I don’t think addressing that is a quota-filling task. I think it’s about going into communities and starting with the grassroots. Where are we employing people from? How do we expand to recruit from new communities, schools and universities across the country and world?

Also, I think unconscious bias has a huge part to play. In this country, it seems like some people think that when you don’t see overt racism, then it doesn’t exist. I think it’s more subtle and more nuanced, which makes it hard to challenge. We all have biases we don’t think about, so that kind of introspection is really important.

What is one really interesting thing that you’d like everyone to know?

I’d like people to know how close connections are related to healthy longevity.

Aside from exercise, good meaningful relationships are the best thing for long-term health. So go and make connections, volunteer, enjoy your hobbies and just make time to meet like-minded people. Friendship – it really is the key to a long and healthy life.

If you could work with any scientist, living or dead, who would you want to work with?

The scientist I would most loved to have met is Wangari Maathi. She was born in Kenya (as was I, so very close my heart) and after winning a scholarship to study biology in the US, she was the first woman in Central and East Africa to gain a doctorate. She recognized that deforestation was causing a decrease in biodiversity and food crops, affecting mainly women who are the resource gatherers in many African communities. She founded the Green Belt Movement which paid local women to plant trees. The Movement grew to encompass almost a million people and had major political ramifications in Kenya.

In 1990 she set up her own political party and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.

I think Dr Maathi’s ability to apply her science to a grass roots problem and make rapid impact in improving the lives of people in her community is incredibly aspiring. I would love to be able to do similar work in the future, using my background in biological research to bring about positive changes in healthcare for individuals.

You’ve also done some really interesting outreach work in the past, right? Can you tell me about that?

Yes, I have a longstanding interest in getting scientists out of their labs and involved in other areas and in communities.

In Newcastle, we had a collaboration with a Fine Art course, creating installations that drew on all kinds of science themes. We then went on to work with the National Trust’s Women in STEM project, with award-winning artist Olivia Turner. We created these amazing 6-foot wooden sculptures that are now on display in the Cheeseburn Sculpture Park.

I’m very keen to re-establish that kind of project in Oxford, too! I’m meeting and liaising with various groups, so watch this space.