Features

Professor Daniela Bortoletto of Oxford University’s Department of Physics explains how a new result from the Large Hadron Collider sheds vital light on the elusive Higgs boson.

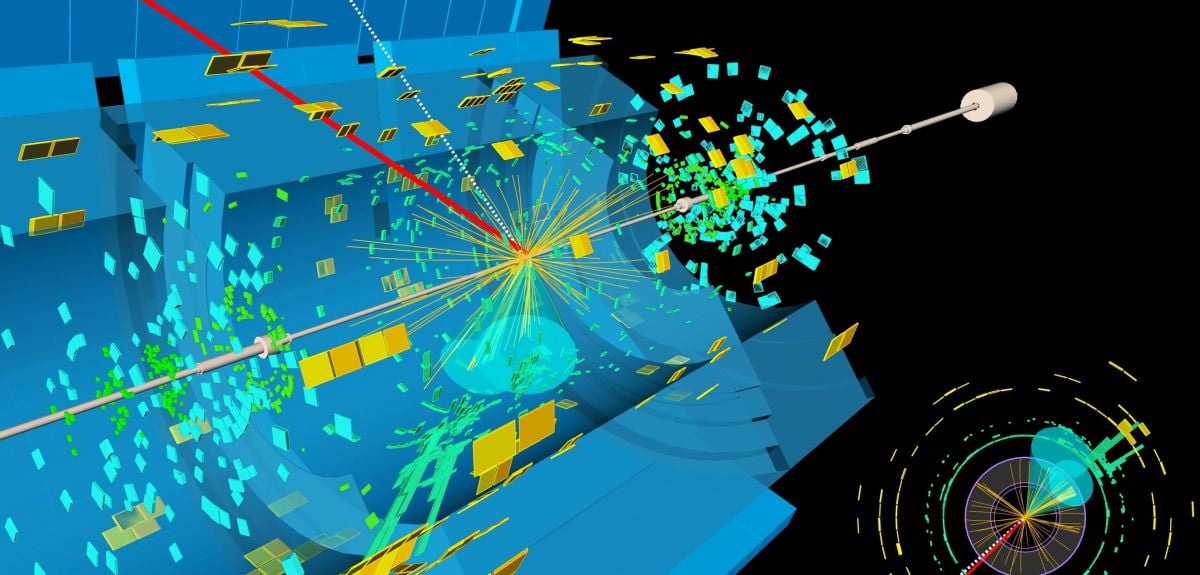

Particle physicists have – at long last – observed the Higgs boson decaying into a pair of bottom (b) quarks at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). This elusive interaction is predicted to make up almost 60% of the Higgs boson decays. Yet it took over seven years to accomplish this observation. This discovery was announced at CERN on August 28 both by ATLAS and CMS.

ATLAS is one of the four major experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. It is a general-purpose particle physics experiment run by an international collaboration and, together with another experiment, CMS, is designed to exploit the full discovery potential and the huge range of physics opportunities that the LHC provides.

The result is a confirmation of the Standard Model. During the early preparations of the LHC, there were doubts on whether this observation could be achieved. Our success is thanks to the excellent performance of the LHC and the ATLAS detector, and the application of highly sophisticated analysis techniques to our large dataset.

UK groups including the Universities of Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool, Queen Mary, Oxford and UCL have made important contributions to this historic achievement.

Finding Higgs boson decaying into a pair of b quarks at the LHC is challenging. Since the LHC collisions produce b-quark pairs in great abundance it is essential to select events where the Higgs boson appears alongside a W or Z particle, which makes the events easier to tag. Our team in Oxford analysed elusive W and Z bosons decays where the decay products of these particles are not directly identified in the detector but are inferred from a large transverse energy imbalance in the event.

Our postdoc researcher, Elisabeth Schopf and my students, Cecilia Tosciri and Luca Ambroz, made significant contributions to the result. Elisabeth played a leading role in optimizing the sophisticated machine learning algorithms that allowed ATLAS to increase the sensitivity to these events. Luca established a new technique that used Monte Carlo events in a clever way and lead to a higher expected significance for the analysis. Cecilia upgraded a method to improve the resolution achieved in the measurements of the decay of the Higgs boson into b-quarks.

This is a very special moment for me personally, and the culmination of an even longer wait. I started looking for the decays of the Higgs boson to b-quarks at the US proton-proton TEVATRON collider with the CDF detector in 2005. Four of my former students completed their theses on searches for the Higgs in events with large transverse missing energy and b-quarks between 2007 and 2012.

The results of this work were used in the final TEVATRON combination which reached about three standard deviations in 2012 - not enough for a discovery. I am delighted that the LHC finally unveiled this important decay mode of the Higgs boson. I did not have any doubt that at the end of this tour de force we will pass the significance of five standard deviations which is necessary to claim a discovery. The LHC is a more powerful accelerator than the TEVATRON and ATLAS is a superb detector.

I believe that this measurement will improve our understanding of the mechanism of mass generation and its possible connections with cosmology and astrophysics.

This is also a new confirmation of the so-called “Yukawa couplings”. Similar to the Higgs mechanism, these couplings to the Higgs field provide mass to charged fermions (quarks and leptons), which are the building blocks of matter. Combined analyses of the Run-1 and Run-2 datasets have resulted in the first measurements of these couplings, as seen in the recent ATLAS observation of Higgs boson production in association with a top-quark pair and the observation of the Higgs boson decaying into pairs of tau leptons.

This result also establishes, for the first time, the production of a Higgs boson in association with a vector boson above five standard deviations. ATLAS has now observed all four main production modes of the Higgs boson. These observations mark a new milestone in the study of the Higgs boson, as ATLAS transitions from observations to precise measurements of its properties.

We now have the opportunity to study the Higgs boson in unprecedented detail and will be able to further challenge the Standard Model.

People admire those who build homes for the poor or donate mosquito nets to those at risk of malaria — but they don’t necessarily want them as friends or romantic partners, finds a new study by researchers at Yale University and the University of Oxford’s Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and Department of Experimental Psychology.

Asked to choose between do-gooders and those who place family members and friends first, subjects said they would rather spend time with those who made people close to them a priority, researchers report in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

‘When helping strangers conflicts with helping family and kin, people prefer those who show favouritism, even if that results in doing less good overall,’ said Yale’s Dr Molly Crockett, assistant professor of psychology and senior author of the study.

The researchers created scenarios designed to test a tough moral dilemma: is it better to help a family member or a larger number of strangers? For instance, they asked whether a grandmother who wins $500 in the lottery should give it to her grandson to fix his car, or to a charity dedicated to combating malaria. In another case, a young woman has to decide whether to spend the day with her lonely mother, or building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

Although participants in the study perceived both choices as equally moral, when it came to looking for a spouse or a friend, they preferred those who helped their grandson or spent the day with mum.

‘Friendship requires favouritism — the key thing about friendship is that you treat your friends in a way you don’t treat other people,’ said Oxford’s Dr Jim Everett, first author of the study. ‘Who would want a friend who wouldn’t help you when you needed it?’

In contrast, this preference was reduced when participants were asked about qualities they wanted in a boss and disappeared when asked about desired traits in a political leader — a social role that requires impartiality.

‘A political leader who represented the interests of themselves or their family over the country would be disastrous,’ said Dr Everett.

According to the researchers, these findings suggest a roadblock for ‘effective altruists’ who argue we should donate money to charity to help relieve poverty and disease in the developing world rather than to a local group that would help fewer people.

Over the past month, a team from Oxford's Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme (EWCP) has implemented the first oral vaccination campaign to pre-empt outbreaks of rabies among Ethiopian wolves, the world’s most endangered canid, in their stronghold in the Bale Mountains of southern Ethiopia.

Described as a turning point in the plight to save Ethiopian wolves from extinction, the campaign follows a decade of intensive research, field trials and awareness work led by the University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) and supported by funding from the Born Free Foundation, among others. Working alongside the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority, regular oral vaccination campaigns will now expand to all six extant wolf populations to enhance their chances of survival. There are fewer than 500 Ethiopian wolves in the world, all in the wild and highly exposed to infectious diseases transmitted by domestic dogs.

WildCRU's Professor Claudio Sillero, EWCP director and founder, said: 'Thirty years ago I witnessed an outbreak of rabies which killed the majority of the wolves I had followed closely for my doctoral studies. We have learned much about these wolves and their Afroalpine homes since then. By the time we detect rabies in a wolf population, already many animals are fatally infected and doomed. We now know that pre-emptive vaccination is necessary to save many wolves from a horrible death and to keep small and isolated populations outside the vortex of extinction. I wholeheartedly celebrate the team’s achievement.'

Long-term programmes and targeted research are the cornerstones of biological conservation, as success often relies on an intimate knowledge of the workings of populations, the behaviour of individuals, and the social, political and economic contexts. With a generous donation from pharmaceutical laboratory Virbac of 3,000 SAG2 oral vaccines, EWCP has launched a vaccination strategy, guided by strong empirical information and predictive modelling – and a key component of the National Action Plan for the conservation of the species.

Muktar Abute, EWCP's vet team leader, said: 'Vaccine contained within a meat bait was distributed at night time to three Ethiopian wolf packs. Our target is to immunise at least 40% of all wolves in each population, reaching as many family packs as possible, including the dominant pair – on which pack stability largely depends. We recorded good uptake, with 88% of 119 baits deployed consumed over two nights. Using camera traps we monitored bait consumption, and we will next measure rabies concentration levels in blood to confirm the effectiveness of the vaccine over a larger sample than that of the trials.'

Oral vaccination using SAG2 has been successful in controlling, and even eradicating, rabies in wild carnivore populations in Europe. This approach now raises hope for the survival of one of the rarest and most specialised carnivore species, the Ethiopian wolf. Preventive vaccination can improve the status of other threatened wildlife, and the Ethiopian wolf experience may lead other practitioners to embrace it as part of their conservation toolkit, in a world demanding closer control of pathogens shared by wildlife, domestic animals and humans.

Professor Antoine Jerusalem of Oxford University’s Department of Engineering Science explains how a better understanding of the physical mechanisms behind brain injuries can pave the way for novel therapies and new protective devices.

Blast-induced traumatic brain injury (bTBI) can lead to a range of debilitating conditions with lifelong consequences. It is a type of injury that has unfortunately seen a significant increase in recent terrorist attacks or conflicts such as in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, where improvised explosive devices have proved to have devastating effects on armed forces personnel and civilians.

While these conditions can clearly manifest themselves as neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, the specific mechanisms that link the blast wave physics to the subsequent biological alterations in the brain have remained elusive.

Our research group seeks to understand the physical mechanisms governing brain tissue damage eventually leading to cognitive disorders, to develop better head protection against such blasts.

Through a unique collaboration with Prof. Shi from Purdue University in the US, our group has constructed computer models of rat and human brains to observe how a shockwave damages soft tissue, and how such damage correlates with post-injury oxidative stress distribution in brain tissues. In order to calibrate and validate these models, novel in vivo experiments coupling blast expositions to cognitive tests were conducted in Purdue.

This approach was then applied to a human head model where the prediction of cognitive impairments was shown to match up with the injuries that individuals have been observed to incur.

This novel approach has already created new opportunities. In particular, the mechanical insights from this work have been directly leveraged to propose a new design for helmets, filed as a patent.

The full paper, ‘Cognition based bTBI mechanistic criteria; a tool for preventive and therapeutic innovations,’ can be read in the journal Scientific Reports, in open access. The resulting computer models are also made available.

Researchers at the University of Oxford and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have discovered a new gene that improves the yield and fertilizer use efficiency of cereal crops such as wheat and rice.

The worldwide 20th century ‘Green Revolution’, which saw huge year-by-year increases in global cereal grain yields, was fueled by the development by plant breeders in the 1960s of new high-yielding dwarfed varieties known as Green Revolution Varieties (GRVs).

These dwarfed GRVs remain predominant all over the world in today’s wheat and rice crops. Because they are dwarfed, with short stems, GRVs devote relatively more resources than tall plants to growing grain rather than stem, and are less susceptible to yield losses from wind and rain damage. However, growth of GRVs requires farmers to use large amounts of nitrogen-containing fertilizers on their fields. These fertilizers are costly to farmers and cause extensive damage to the natural environment. Development of new GRVs combining high yield with reduced fertilizer requirement is thus an urgent global sustainable agriculture goal.

A major new study published in the journal Nature, led by Professor Xiangdong Fu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, and Professor Nicholas Harberd from the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of Oxford, part-funded by the BBSRC-Newton Rice Initiative, has for the first time discovered a gene that can help reach that goal.

Comparing 36 different dwarfed rice varieties, the study identified a novel natural gene variant that increases the rate at which plants incorporate nitrogen from the soil. The discovered gene variant increases the amount in plant cells of a protein called GRF4. GRF4 is a ‘gene transcription factor’ that stimulates the activity of other genes – genes that themselves promote nitrogen uptake and assimilation.

Professor Harberd said: ‘Discovering such a major regulator of plant nitrogen incorporation was exciting in itself. But we were even more excited to then discover that GRF4 has a yet broader role. Plants grow by the coordinated metabolic incorporation of matter from the environment. We discovered that GRF4 coordinates plant incorporation of nitrogen from the soil with the incorporation of carbon from the atmosphere. While such overall coordinators of plant metabolism have long been known to exist, their molecular identity had previously remained unknown, and our discovery is therefore a major advance in our understanding of how plants grow.’

In dwarf GRVs the promotive metabolic coordinating activity of GRF4 is inhibited by a growth-repressing protein called DELLA. This inhibition reduces the ability of GRVs to incorporate nitrogen from the soil, and is the reason why farmers need to use high fertilizer levels to obtain high GRV yields.

Professor Harberd said: ‘We reasoned that tipping the GRF4-DELLA balance in favor of GRF4 might reduce the need for high fertilizer levels in GRV cultivation. To our delight, we found that increasing GRF4 levels caused an increase in the grain yields of both rice and wheat GRVs, especially at low fertilizer input levels.’

The researchers say GRF4 should now become a major target for plant breeders in enhancing crop yield and fertilizer use efficiency, with the aim of achieving the global grain yield increases necessary to feed a growing world population at reduced environmental cost.

Professor Harberd added: ‘This study is a prime example of how pursuing fundamental plant science objectives can lead rapidly to potential solutions to global challenges. It discovers how plants coordinate their growth and metabolism, then shows how that discovery can enable breeding strategies for sustainable food security and future new green revolutions.’

- ‹ previous

- 67 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria