Features

John Humphrys, the presenter of Radio 4's Today programme, can strike fear into prime ministers and CEOs. But he was no match for Oxford University classicist Cressida Ryan in an interview this week.

In an interview to mark Grammar Day Mr Humphrys asked whether English words which sound as if they are derived from Latin should take Latin plural endings, for example bacteria rather than bacteriums and referenda rather than referendums.

Dr Ryan said: 'There are three issues here: what is correct Latin? What is correct English? What is the relationship between those two? It depends whether you are using something as a Latin word you have borrowed, or if you are choosing to use it as an English word.'

Dr Ryan pointed out that English is a living, flexible language that can accommodate different ways of expressing the same word. She said: ‘People in particular technical business will use words in a particular way for them that might different from people in other parts of the country because English is a language which has regional dialects, temporal dialects, and describes different things in different ways.

‘So it is fair to use bacterium in the singular form. But if you wanted to talk about a class of things then bacteria sounds perfectly fair as a collective noun.

'The more Latin you do at school or university, the more you realise how quickly linguistic change happens and how dynamic languages are.'

Dr Ryan pointed out that the collective wisdom about how a word should correctly be written is often wrong. 'For 'syllabus', actually the plural in Latin would still end in 'us' but most people think it would be syllabi,' she said. 'In Italian, panino would be the singular of panini, but in the UK we use panini as the singular when ordering in a restaurant.'

She then added: 'There's one other aspect to this, which is that bacteria is in fact singular and a Greek word.'

To the sound of background laughter in the studio, Mr Humphrys could only reply: 'Ah. You’ve silenced me.'

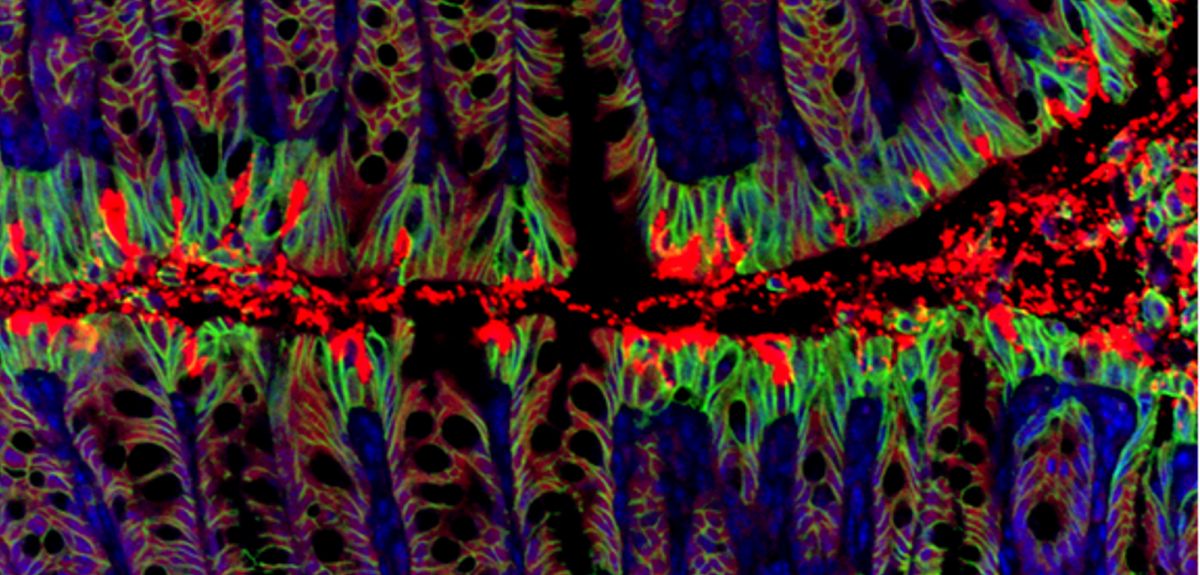

There's an odd-looking Perspex box sat on a workbench in one corner of Professor Fiona Powrie's lab. It's not much to look at. It's a see-through box with flasks inside, in which bacteria are grown at body temperature – as is done in thousands of molecular biology labs around the planet. But there's a glove box on the front with seals to prevent the outside air getting in. That's because these bacteria are grown under oxygen-free conditions, the same conditions as are found inside your belly.

'The gut is the wild west of the body,' says Dr Claire Pearson, a postdoc in the Powrie lab in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine. 'There's food, bacteria and foreign things, but how does the gut distinguish the good, the bad and the ugly?'

In terms of numbers of cells in our bodies, we're actually more bacteria than we are human, Claire explains. Many bacteria in the gut are really helpful for digesting food. We need this flourishing ecosystem of different bacteria populating our insides. But when it comes to "bad" bacteria, it's immune cells including some called T cells that act as sheriff to take down those invasive strains and run them out of town.

We might be largely unaware of this showdown taking place in our insides, but Professor Powrie and her lab colleagues are taking the gunslinging duel between our immune cells and the bacteria colonising our colons to the Royal Society’s annual Summer Science Exhibition that begins today.

The exhibition sees large numbers of visitors each year, from school groups to tourists, and makes the best of cutting-edge British science fun for all.

On the Powrie lab's stand, you’ll be treated to an interactive exhibit where you can build your own gut on a giant wall, complete with fluffy bacteria. There'll be a shoot 'em up game to blast the bad bacteria out of the gut, but not the good bacteria. You'll be able to look at your own cells under the microscope and spot all the bacteria living on you, all taken from a swab inside your mouth. And, er, bringing up the rear, there'll be endoscopy videos so it's possible to see the difference between an inflamed bowel and healthy intestines.

'We need to have a balance between our immune response and the bacteria in our gut,' says Claire. 'When this balance breaks down, it can lead to inflammation and disease. This is what we see in inflammatory bowel disease.'

Understanding this balancing act is what the Powrie lab is interested in: How are the complex interactions maintained between immune cells, tissues in the gut and the diverse bacteria living in the gut? And what leads immune responses to spiral out of control and damage the intestinal tissue?

This isn't just an academic pursuit. Their Translational Gastroenterology Unit is linked to the John Radcliffe hospital, allowing studies with human tissue samples and clinical studies with patients. New insights that lead to improved treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) could make a great difference to patients.

IBD is thought to affect around 261,000 people in the UK. The bowels become swollen and sore and common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhoea (sometimes with blood), abscesses, weight loss and tiredness. There are two types – Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis – but both are chronic, incurable diseases that flare up unpredictably, making them very difficult conditions to live with. While people experience different severities of disease, in many the condition progresses and eventually needs surgery to remove parts of the intestine.

Professor Powrie played an instrumental role in identifying the role of a subset of immune cells called regulatory T cells (Treg cells), and her lab continues to work on these cells.

'Regulatory T cells are key for harmony in the gut. They police immune cells to keep their response under control, releasing factors that suppress the T cell response,' explains Claire Pearson. 'This balance can break down in IBD.'

The group continues to be interested in the role of different immune cell types in disease, how Treg cells function through the compounds (cytokines) they secrete, and how that cytokine secretion varies in different sites in the gut.

Understanding all the cellular processes that are involved could pinpoint new targets for drug development, says Claire.

The Royal Society’s Summer Science exhibition opens to the public today and runs until Sunday.

Why are we entertained by evil? Who has the capacity to commit evil? These questions were considered by 90 delegates from around the world who met in Oxford today (Friday 27 June) for a conference exploring the concept of evil, and what role it plays in human experience.

The conference, entitled Evil: Interdisciplinary Explorations, was organised by Oxford University theologian Kate Kirkpatrick and linguist Marieke Mueller, with the support of The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), Wycliffe Hall, the Faculty of Theology and Religion, and the Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture.

Discussions at the conference touched on evil in many forms: from fictional representations of devils, monsters and murderers, to institutional evil and the relationship between evil and technology.

Kate Kirkpatrick, of St Cross College and the Faculty of Theology and Religion, said: 'We've had a fantastic level of interest, including delegates from North America, Europe, and Australia, as well as around the UK. We're aiming to get people from different fields to talk to each other and share their ideas.

'It's a question of dispute whether it’s possible for anyone "not to have a bad bone in their body", or to be perfectly evil. Do we call individual actions evil, or do people have evil characters?

'If someone is pure evil, does that make them responsible for their actions, or do they not have a choice? If you put ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances they will sometimes do heinous things.'

Many speakers explored our cultural fascination with evil, from Shakespeare to serial killers. Professor Terry Eagleton of Lancaster University gave the closing lecture, on William Golding’s novel, Pincher Martin, which deals with a shipwrecked man’s struggle to survive and eventual descent into madness.

Horror films and contemporary television also came under scrutiny. 'It makes one wonder whether evil is a more interesting concept than good,' said Kirkpatrick.

The conference was held in the Andrew Wiles Building and Radcliffe Humanities Building, part of the University's Radcliffe Observatory Quarter.

Image: A depiction of evil from Gustave Doré's illustrations to Dante's Inferno.

The weirdness of quantum theory has caused some physicists, including Einstein, to suggest that it doesn't give us a picture of the way the world is.

Viewed this way, quantum theory might just be a mathematical tool for making predictions about an object without describing what it's really like. If this was true, a single object could be described by more than one quantum state.

Now scientists at Oxford University and the University of Sydney have shown that the idea of objects with multiple quantum states may be an illusion that could vanish as experimental measurements become more precise. If they are correct it could help to chart the limitations of quantum information processing [QIP].

A report of the research is published this week in Physical Review Letters.

The team liken trying to understand the nature of objects from experimental observations of quantum states as a bit like trying to determine how a playing card was chosen from being dealt a single playing card.

'Imagine a deck of 52 playing cards is shuffled by a special shuffling robot,' explains Owen Maroney of Oxford University, an author of the study. 'The robot has two settings, with the first it deals you a red card drawn at random and with the second it deals you one of the four aces at random. You have to deduce what's really going on from just one card, but if you are dealt the ace of hearts then you can't distinguish if the robot was using setting one or two.'

This is because the cards dealt out by settings one and two overlap in the case of the ace of hearts. Two different quantum states can also show 'indistinguishability' – sometimes you just can't tell whether an object is in one quantum state or another. This led some physicists to suggest the same explanation.

'Rather like with the playing cards, when quantum states seem to overlap the problem could lie in the way that the state is prepared,' Owen tells me.

'What we have shown is that this puts a strong limitation on experiments performed on three different states, and we've found quantum states that exceed this limitation.'

This question of whether quantum states are grounded in reality or not is an important one for anyone trying to use the 'weirdness' of the quantum world to do advanced calculations or form the basis of a quantum computer.

'We're exploring the fundamental limits of what information can be squeezed out of quantum states from what we can detect,' Owen explains.

The team are currently working with three different labs on experiments to see whether the limitations they have scoped out can be tested.

'The best experimentalists are only just reaching the 99% accuracy in reading quantum states that we need to be able to test our ideas,' Owen says. 'We still don't know for sure what the real boundaries are between what classical and quantum computing can do, it may be that we are reducing quantum problems to classical ones. Our work isn’t just about the limitations; it could lead to new opportunities for quantum information processing.'

Forget Cannes, move over Sundance. The Radcliffe Humanities building will host a film festival on public health next week.

The Public Health Film Festival, which will take place on Friday 27, Saturday 28 and Sunday 29 June, has been organised by public health students and practitioners from Oxford.

Through the medium of film, the organisers aim to facilitate discussion and debate about the big public health issues of the day and provide a springboard for action to reduce poverty, improve social inclusion, and provide advocacy for marginalised communities.

The Oxford Centre for Research in the Humanities (TORCH) is hosting several screenings and sponsoring a prize, along with the Nuffield Department of Population Health. TORCH's director Dr Stephen Tuck says: 'We are delighted to support the Public Health Film Festival. It demonstrates how arts and sciences can work together for the public good, by using techniques of film and advocacy - which are more often associated with the arts - to support scientific, evidence-based cases for reform to public health policies.'

One of the films, Unborn, is shown below. Directed and produced by Dr Oliver Rivero, senior health economist at Oxford's National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, it shows a young woman who suffered a miscarriage dealing with feelings of sadness and self-blame when she sees a happy mother with her baby in a park.

Another film that will be shown, called 'Sea of change: Walking into trouble', has been used for advocacy for the partially sighted and blind at Number 10 Downing Street and the House of Lords.

Sarah Gayton, who made the film to support her campaign, says: 'I decided to use to film as I thought this way the people in charge of the safety of the public could see first-hand the negative impact this road system was having on the blind and partially sighted people of the UK.'

Dr Stella Botchway, a Public Health Speciality Registrar in Oxford University's Nuffield Department of Population Health and organiser of the Public Health Film Festival, says: 'Public health in the UK and around the world is the key issue of our time. Diet, social inequality, the global economy, the control of infectious diseases and climate change are just a few of the challenges facing public health experts.

'The Public Health Film Festival passionately believes that both film and public health have the ability to change people’s lives, which is why we have brought these two disciplines together in order to inform and inspire the public.'

A full schedule of events can be found on the Public Health Film Festival’s website. Screenings and talks will take place in Radcliffe Humanities on Woodstock Road and the Phoenix Picturehouse on Walton Street.

- ‹ previous

- 167 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria