Shootout at the OK Colon

There's an odd-looking Perspex box sat on a workbench in one corner of Professor Fiona Powrie's lab. It's not much to look at. It's a see-through box with flasks inside, in which bacteria are grown at body temperature – as is done in thousands of molecular biology labs around the planet. But there's a glove box on the front with seals to prevent the outside air getting in. That's because these bacteria are grown under oxygen-free conditions, the same conditions as are found inside your belly.

'The gut is the wild west of the body,' says Dr Claire Pearson, a postdoc in the Powrie lab in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine. 'There's food, bacteria and foreign things, but how does the gut distinguish the good, the bad and the ugly?'

In terms of numbers of cells in our bodies, we're actually more bacteria than we are human, Claire explains. Many bacteria in the gut are really helpful for digesting food. We need this flourishing ecosystem of different bacteria populating our insides. But when it comes to "bad" bacteria, it's immune cells including some called T cells that act as sheriff to take down those invasive strains and run them out of town.

We might be largely unaware of this showdown taking place in our insides, but Professor Powrie and her lab colleagues are taking the gunslinging duel between our immune cells and the bacteria colonising our colons to the Royal Society’s annual Summer Science Exhibition that begins today.

The exhibition sees large numbers of visitors each year, from school groups to tourists, and makes the best of cutting-edge British science fun for all.

On the Powrie lab's stand, you’ll be treated to an interactive exhibit where you can build your own gut on a giant wall, complete with fluffy bacteria. There'll be a shoot 'em up game to blast the bad bacteria out of the gut, but not the good bacteria. You'll be able to look at your own cells under the microscope and spot all the bacteria living on you, all taken from a swab inside your mouth. And, er, bringing up the rear, there'll be endoscopy videos so it's possible to see the difference between an inflamed bowel and healthy intestines.

'We need to have a balance between our immune response and the bacteria in our gut,' says Claire. 'When this balance breaks down, it can lead to inflammation and disease. This is what we see in inflammatory bowel disease.'

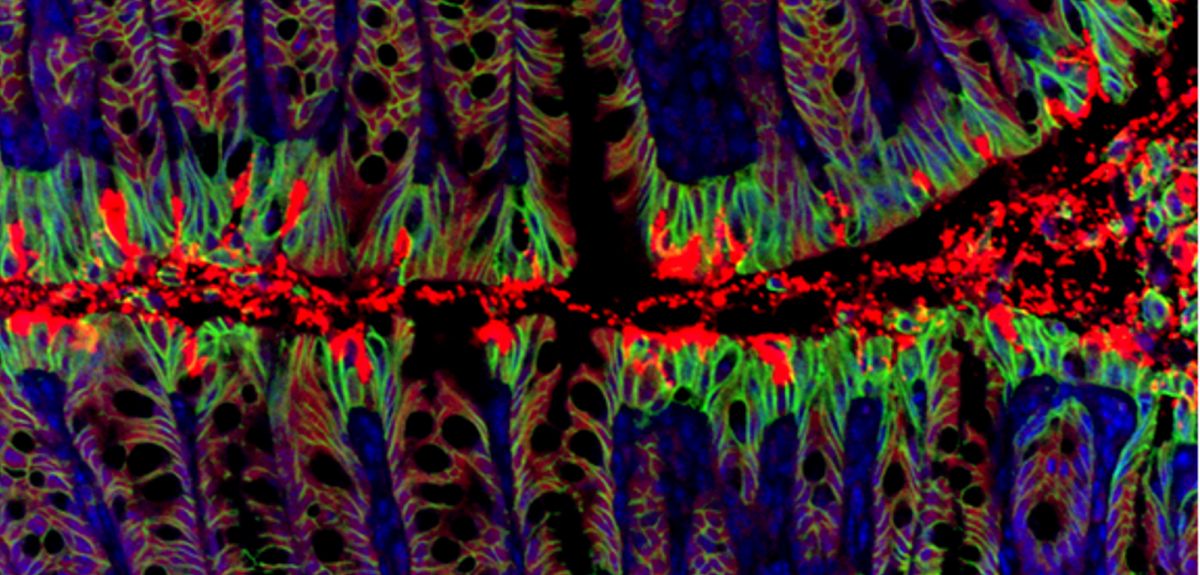

Understanding this balancing act is what the Powrie lab is interested in: How are the complex interactions maintained between immune cells, tissues in the gut and the diverse bacteria living in the gut? And what leads immune responses to spiral out of control and damage the intestinal tissue?

This isn't just an academic pursuit. Their Translational Gastroenterology Unit is linked to the John Radcliffe hospital, allowing studies with human tissue samples and clinical studies with patients. New insights that lead to improved treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) could make a great difference to patients.

IBD is thought to affect around 261,000 people in the UK. The bowels become swollen and sore and common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhoea (sometimes with blood), abscesses, weight loss and tiredness. There are two types – Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis – but both are chronic, incurable diseases that flare up unpredictably, making them very difficult conditions to live with. While people experience different severities of disease, in many the condition progresses and eventually needs surgery to remove parts of the intestine.

Professor Powrie played an instrumental role in identifying the role of a subset of immune cells called regulatory T cells (Treg cells), and her lab continues to work on these cells.

'Regulatory T cells are key for harmony in the gut. They police immune cells to keep their response under control, releasing factors that suppress the T cell response,' explains Claire Pearson. 'This balance can break down in IBD.'

The group continues to be interested in the role of different immune cell types in disease, how Treg cells function through the compounds (cytokines) they secrete, and how that cytokine secretion varies in different sites in the gut.

Understanding all the cellular processes that are involved could pinpoint new targets for drug development, says Claire.

The Royal Society’s Summer Science exhibition opens to the public today and runs until Sunday.

Counting quantum cards

Counting quantum cards Blasting back to the Big Bang

Blasting back to the Big Bang Explosions, volcanoes & risks

Explosions, volcanoes & risks Valuing our oceans

Valuing our oceans Unfolding role of cell's gatekeepers

Unfolding role of cell's gatekeepers