Features

The "cradle of civilisation" is further east than you might have read in history textbooks at school, according to a new book by an Oxford academic.

The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, which is published this month by Bloomsbury, has been written by Peter Frankopan, Director of the Centre for Byzantine Research in the University's History Faculty.

Described as a "major reassessment of world history", Dr Frankopan’s book shows the importance of the 'east' (i.e. the region between eastern Europe and China and India) in developing the world's civilisation and religions.

He looks at countries which were crossed by the 'Silk Roads', which were trading networks that connected the West to East and spread led to cultural transmission between the two areas.

He says countries along this route have been overlooked by history, such as Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, and Nepal. Even the role of India and China has been downplayed.

'While such countries may seem wild to us, these are no backwaters, no obscure wastelands,' he says. 'They are the very crossroads of civilisation. Far from being on the fringe of global affairs, these countries lie at its very centre — as they have done since the beginning of history.

'The Silk Roads were no exotic series of connections, but networks that linked continents and oceans together. ‘Along them flowed ideas, goods, disease and death. This was where empires were won – and where they were lost.'

Dr Frankopan says the prominence of western Europe since the 16th century caused this 'rewriting' of the past. 'Ancient Greece begat Rome, Rome begat Christian Europe, Christian Europe begat the Renaissance, the Renaissance begat the Enlightenment, the Enlightenment political democracy and the Industrial Revolution,' is how he describes this traditional assumption.

But in fact, it is actually western Europe, and Britain at its periphery, which was a relative 'backwater', he says. The Greeks and Romans had little interest in Europe, and letters sent home by Roman soldiers reveal that being sent to Europe or even Britain was an unwelcome prospect.

'The Greeks and Romans looked to the East,' says Dr Frankopan. 'Riches from the East paved the way for Rome's grandeur and the Silk Roads were the conduit for Eastern commerce, wealth, enlightenment and technology.'

The Silk Roads: A New History of the World can be ordered from Bloomsbury.

70 years ago today, the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima in Japan.

Professor Rana Mitter, an historian who specialises in the history and politics of China and Japan, and Nigel Biggar, Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology, explain the significance of the anniversary and the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Professor Mitter says the memory of the bomb has put the Japanese population off the idea of nuclear weapons forever. 'The horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has so much ingrained itself in the popular consciousness in Japan that it seems to me impossible that they would ever find a way to have their own nuclear weapons,' he explains.

Professor Mitter puts the bombing in the context of Asia, rather than just looking at relations between the USA and Japan. 'What is often forgotten is that the lead-up to the A bomb against Japan was the Japanese invasion of large parts of Asia where over 14 million Chinese were killed.

'Therefore we have to remember, balancing the horror of Hiroshima which we’ve heard so much about today and must never be allowed to happen again, with the fact that there was a context which people in Asia still remember quite clearly.'

Professor Biggar applies the "Just War" theory in Christian theology to the events. He says: 'If the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to use the mass slaughter of civilians to terrorise the Japanese government into surrender, then that is immoral.

'If on the other hand the bombs were dropped to hit important military targets and there was no other way of hitting those targets other than endangering the lives of civilians, according to Just War thinking that could have been morally permissible. Which of those two cases fits the facts, you would have to ask an historian. I suspect it was the first.'

He adds: 'From the beginning Christians have disagreed about whether following Jesus means you can use force on any occasion. I think that one may use it under certain circumstances but only as a last resort, never in vengeance and only as strictly necessary.'

Professor Mitter was interviewed about Hiroshima on the Today programme (at 2 hours 53 minutes) and Professor Biggar on All Things Considered, both on Radio 4.

Elleke Boehmer is Professor of World Literature in Oxford University's Faculty of English Language and Literature. She is also a published novelist. She has recently brought out a novel and will publish a major academic book in September. Professor Boehmer tells Arts Blog that each kind of writing can help the other.

AB: Your latest novel, The Shouting in the Dark (Sandstone Press), has just been published. Is it difficult to write fiction alongside writing academic books?

EB: Yes, the business of producing more than one kind of writing probably does look challenging, and there definitely are different demands on your energy and focus when you're writing fiction as against when you're writing academic books.

In fiction, there is more of a demand to keep the writing concentrated in whatever centre of consciousness, of the character or the narrator, that you as a writer are dealing with. In The Shouting in the Dark this definitely is the case, and I reworked the book nearly twenty times to get it absolutely right.

In academic writing the push is to stand a little to the side of the material and analyse. But ultimately in both kinds of writing, the thinking is happening through the writing. My gut feeling is that similar parts of the brain are firing.

It took me a while to come to this understanding though. I've been writing fiction alongside non-fiction for over 25 years now, and at first I did tend to think two different kinds of processes were involved. Thinking that used to make me feel very tired!

Can writing fiction improve your non-fiction writing or are they very separate things?

Definitely the different kinds of writing can help each other out. The things you learn about controlling language, and the structure of 'thought units', like paragraphs, work across and between the different strands.

Are there ways in which your research has informed your novels?

Yes, research does inform my novels, especially when I get fascinated by a topic I'm researching, but this isn't always beneficial for the fiction. One of my novels, Bloodlines, published in 2000, had as its imaginative springboard the fact that Irish republican soldiers fought in the Anglo-Boer War in 1899-1902, and mingled while in the Transvaal with local people.

I got stuck into a huge amount of research, including in the National Library of Ireland, which was very enjoyable, but in the end the research perhaps weighed too heavily on the story element.

Marina Warner calls this the green light of the study lamp shining through. With fiction, character or voice has to convince, not the scholarship.

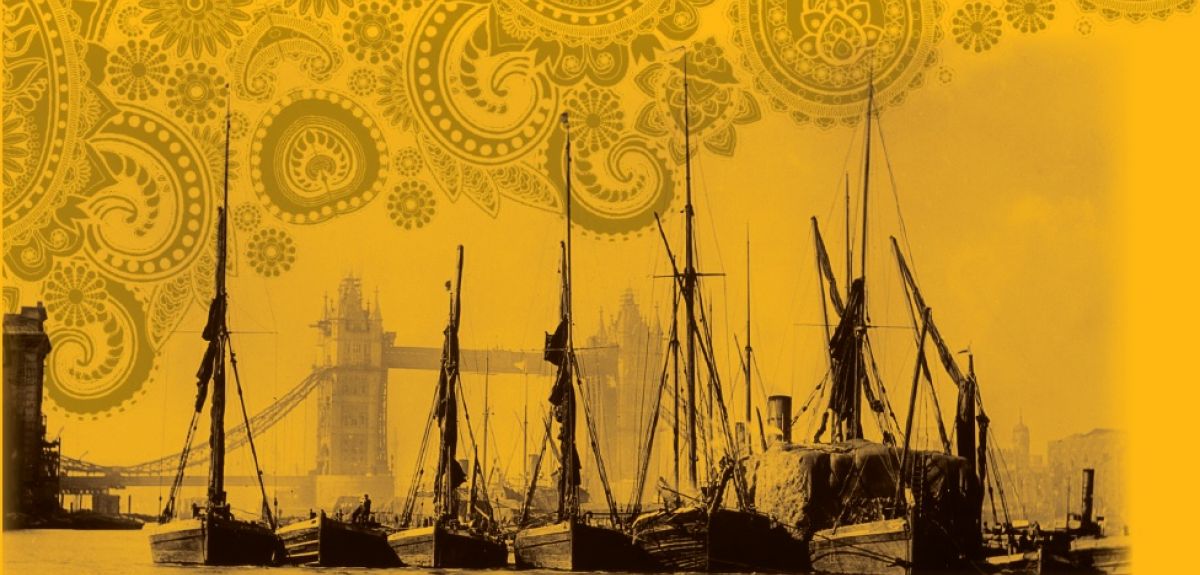

Your next academic book, Indian Arrivals, 1870-1915 (OUP), comes out in September. What is it about?

Indian Arrivals 1870-1915 is about turn of the century Indian travellers who wound their way through Suez to Britain, and the interesting and unexpected impacts that had on cultural and literary life over here, including shaping London's sense of itself as cosmopolitan and modern.

If, as is now widely accepted, vocabularies of inhabitation, education, citizenship and the law were in many cases developed in colonial spaces like India, and imported into Britain, then, the book suggests, the presence of Indian travellers and migrants needs to be seen as much more central to Britain’s understanding of itself, both in historical terms and in relation to the present-day.

The book demonstrates how the colonial encounter in all its ambivalence and complexity inflected social relations throughout the empire, including at its heart.

What sources did you use when researching the book?

Particularly useful sources were the manuscripts of the poets Sarojini Naidu and Rabindranath Tagore, which revealed how their work was frequently composed and translated en route, while travelling, and often on ships, so their works literally were 'travelling' documents.

I also read many English language newspapers of the time, including from India, which showed how cosmopolitan educated Indians felt they were, even when they hadn't yet left their homeland. The censuses of 1901 and 1911 were also very revealing, reflecting how surprisingly many people with Indian surnames lived around Britain's docklands at this time.

'A post-antibiotic era – in which common infections and minor injuries can kill – far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.'World Health Organisation Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance 2014

Around the world, governments are taking action to tackle the growing issue of anti-microbial resistance (AMR). In a number of countries, more than half of infections by some bugs are resistant to common treatments.

In Vietnam, the government is committed to confronting the issue. So in a recent ceremony four Vietnamese government departments signed an aide memoire on combating AMR with the World Health Organisation, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation. The other signatory was Oxford University, reinforcing the importance of the Vietnam-based Oxford University Clinical Research Unit (OUCRU) to healthcare in the South East Asian nation.

OUCRU, one of the Wellcome Trust’s major overseas programmes, has had key partnerships with the National Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Hanoi since 2006 and the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in Ho Chi Minh City since 1991. Its research covers a range of areas from tuberculosis to dengue fever. Currently, the unit is advising the government of Vietnam on a national action plan to counter anti-microbial resistance (AMR).

Professor Heiman Wertheim is the Director of Oxford University Clinical Research Unit Hanoi. He explains that AMR is a growing issue in Vietnam:

'In the community, 90% of the antibiotics are sold over the counter even though there is a prescription law. Most antibiotics are dispensed for acute respiratory infections, which are mainly viral and do not need antibiotics.

'What we see in the intensive care units of large hospital is that last resort antibiotics like carbapenems or colistin are being used frequently. Compare that to northern Europe, for example, where these drugs are rarely used. The issue in Vietnam is similar to that in other Asian countries like India and China.'

Another issue is the use of antibiotics in agriculture. In poultry and pig productions antimicrobials are typically used to prevent rather than to treat clinical disease. Most commercial animal feed is medicated with antibiotics. The amount of antimicrobials used to raise poultry is in the order of 5 – 7 times higher than in European countries.

Such widespread and indiscriminate use drives bugs to develop resistance, eventually rendering them immune to common treatments. Some countries have already taken steps to reduce the unnecessary use of anti-microbials to stave off this resistance, and Vietnam is set to join them.

So what does the new aide memoire mean for Vietnam?

Professor Wertheim explains: 'The Aide Memoire says that the partners will do everything they can within their means to combat AMR. This is the starting point of getting the funds and expertise needed to combat AMR. Those could be directed to developing surveillance strategies, diagnostics, treatment guidelines, education, awareness campaigns, research, policy development, and so on.'

OUCRU's main role will be supporting decision makers by providing research evidence to shape policy. The unit carries out clinical trials on how to best treat drug resistant infections, which provide important information to policy makers. In agriculture, they conduct studies on how antibiotic use there impacts on AMR and how this could be controlled.

Professor Wertheim adds: 'We work closely with the National Hospital of Tropical Diseases, a leading infectious disease hospital in Vietnam, and with them we plan to set up a national antibiotic resistance reference laboratory and a national AMR surveillance scheme.'

In Vietnam, Oxford researchers focus on four main areas:

- Emergence: looking at how and why antibiotic resistance is developing.

- Prevention: working out how best to prevent resistance developing.

- Alternative treatment options: to find the best treatment options for antimicrobial resistant infections.

- The role of agriculture: to identify of the main drivers of antimicrobial use and resistance in animal production.

Current research includes a study of how resistant infections occur, which looks at patients treated in hospital and those treated in the community. Other researchers are looking at improving the diagnosis of simple infections in primary health care. A further study is looking at pharmacy and prescribing practices to find ways of reducing unnecessary antibiotic use. Apart from AMR in people, researchers are investigating the dynamics of antimicrobial resistance in pig and poultry farms.

Tackling AMR is a big project, with changes required in many areas. The key question is whether it can make a difference. Professor Wertheim believes that it will, but it will take time and a commitment by all partners to work together and coordinate their efforts.

'I am confident that useful policies and interventions will be implemented though it may take a long time to see any effect. The magnitude of how antibiotics are being wasted currently can be changed and this could have a huge impact. If new antibiotics come to the market, we want to ensure these are used with more thought. To do this you need to create behavioural change, besides diagnostics and guidelines. That is a challenge.

'Another challenge is that all the stakeholders need to work together constructively and be complementary. Often you see organizations do similar work but with different methodologies which is a waste of resources. The best way will be to work together and harmonise what we do.'

The killing of Cecil the lion has caught the public's attention: he was one of the lions fitted with a GPS collar as part of Oxford University research led by Andrew Loveridge.

UPDATE: You can read a response to Cecil's death from Oxford's Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU).

Below we revisit an interview with Andrew about his research first published in 2012. You can support WildCRU lion research here.

Photo: Andrew Loveridge

They are one of the world’s most charismatic big cats, but what does it take to understand the lives of wild lions?

Someone who knows is Andrew Loveridge of Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), who has been studying lions in Zimbabwe for over a decade and recently won the SATIB Trust Award for his lion biology and conservation work.

I asked Andrew about how he tracks and studies lions, gaining insights into lion behaviour, and how people can live alongside these iconic predators…

OxSciBlog: What are the challenges of studying lions in the wild?

Andrew Loveridge: Lions tend to live in the last wilderness areas of the planet - and these are naturally remote and often fairly inhospitable to people (the reason they remain wilderness areas in the first place). Most people visualise Africa as being Disney-like wide open plains, and while plains habitats do exist in Africa, much of the continent is more densely wooded.

Hwange, the National Park we work in, is one such place being thickly wooded bushland-savannah with very few access roads. Lions in this ecosystem have home ranges in excess of 300km2 so they are typically tricky to find and study.

Monitoring enough of the population to provide a meaningful scientific insight into population processes and behaviour presents quite severe logistical challenges. We overcome this by covering extensive areas in 4X4 vehicles - often spending weeks at a time camping in remote areas of the park, by using technology such as GPS radio-collars (and recently GPS collars that return our data via satellite) and having access to a micro-light aircraft which helps us locate lions more easily.

Of course all this requires considerable funding to put in place and maintain, so outside the field the biggest challenge is raising the funding to maintain the study. We have been very fortunate in recent years to have received substantial grants from Panthera, Thomas and Daphne Kaplan, and recently the Robertson Foundation, as well as ongoing support from the SATIB Trust.

OSB: How can fieldwork studies help to inform conservation efforts?

AL: A common misconception is that lions are common and widespread in Africa. Whilst it is true that lions are commonly sighted in some of Africa’s well protected photographic safari destinations they fare less well in areas with limited or no protection. In such areas they compete with burgeoning human populations for limited space and resources. In the last 50-100 years the geographic range of the African lion is thought to have declined by 80%.

Surprisingly, for such an iconic and well known species, even basic biological statistics such as population size and crude population trends are unknown for many (if not most) lion populations in Africa. Along with our more academically-orientated scientific work we provide local managers and decision makers with the baseline information they need to adequately manage lion and other wildlife populations. In this way our work has a direct influence on conservation planning and policy.

We are only just learning what long term effects human activities, such as trophy huntingand retaliatory killing over livestock loss have on lion populations. A better understanding of these issues helps African conservationists to preserve and manage a species that has huge economic, ecological and cultural importance. Robust conservation decisions need to be based on reliable and detailed biological information.

OSB: What surprises about lion behaviour has your research revealed?

AL: Lions are probably one of the best-studied mammalian species, nevertheless, they still do things that surprise and intrigue our research team. Possibly one of the most intriguing aspects of lion behaviour is their wide ranging behaviour and ability to move over extensive areas. Understanding these movements is one of the key challenges in protecting lion populations because wide ranging carnivores frequently come into conflict with people. Protected areas need to be large to accommodate the ranging behaviour of large carnivores.

The surprisingly extensive movement of our lions was recently illustrated by a male lion that moved from our study area in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, to Livingstone town in Zambia. This movement took just over a month and in this time the lion walked around 220km. He crossed the 100m wide Zambezi River below Victoria Falls, negotiating the substantial white water rapids.

We have recorded extensive ranging movements in the past particularly in young dispersing males. However, this is longest movement and this particular study animal was 10 years old - which makes this behaviour even more intriguing. This demonstrates how little we actually know about movements of lions between regional populations. This is crucial information if we are to avoid population isolation which could spell disaster for the genetic health and long-term viability of large carnivore populations.

The other unique aspect of lion behaviour revealed by our study is the lions’ unusual behavioural responses to the local ecosystem. In the dry season in Hwange National Park water is provided for wildlife at artificially pumped waterholes. These attract high abundances of prey species and our research has revealed that lions configure their rangesto ensure access to this rich prey resource.

Elephants are the most locally abundant herbivore in the area. Because of their massive size elephants are usually not troubled by lions, however lions in our study area have learned to pick out and kill even quite large elephant calves. Elephants make up a significant proportion of lion diet in the ecosystem, particularly in dry years when elephants are stressed by shortage of browse and water.

OSB: How can this research help people to live alongside lions?

AL: The research team in Hwange has just completed the first phase of a human-wildlife conflict project, focused on conflict with lions, but also including species such as the spotted hyaena in the research. This phase has focussed on understanding both the ecological and human economic and sociological factors that contribute to conflict situations. Understanding the root causes of human-wildlife will hopeful allow us to implement locally suitable interventions in the next three-year phase of the project, funded by Panthera and the Robertson Foundation.

In the nearby Makgadikgadi ecosystem in Botswana a recent WildCRU study discovered that lions feed almost exclusively on wild prey when it is seasonally abundant, but in periods of wild prey shortage they switch to killing perennially abundant domestic livestock. Lions appear to weigh up the considerable risks of killing domestic stock by only doing so in times of wild prey scarcity. This pattern is mirrored in the Hwange ecosystem. Here we have found that lion predation on livestock peaks in the wet season.

There are two reasons for this: Firstly water is freely available in thousands of ephemeral waterholes and wild prey disperses widely throughout the ecosystem. This makes wild prey more difficult and less predictable for lions to find. At the same time people in surrounding communities plant their crops in the wet season. Livestock guarding is neglected as people focus on tending their fields, leaving domestic animals vulnerable to predation.

Understanding the underlying ecological processes is the key to putting in place appropriate and successful interventions to ease or eliminate human-wildlife conflict. It would be pointless and expensive to implement inappropriate or ill conceived interventions that do not address the root causes of the problem. To address some of the conflict problems we are designing suitably targeted livestock husbandry systems, investigating the potential use of predator proof fencing and seasonal protective structures. We are employing local men to assist villagers to improve livestock protection and to deter predators.

OSB: How will the SATIB award/land rover help in your work?

AL: It is a huge honour to accept the 2012 SATIB Award, especially knowing how passionate and dedicated Brian Courtenay and the other Trustees of the SATIB trust are to conservation of African wildlife and wild places. It has also been a great opportunity to raise the profile of the lion project and what we are trying to achieve in conservation of the species and its habitat.

Like the species we study, lion researchers have to cover extensive areas of remote and often inhospitable wilderness. Having a tough and reliable off-road-capable research vehicle, such as the specially fitted Land Rover Defender LWB that came with the SATIB award, is an absolutely essential part of undertaking research on this species. In the coming year the project team will also be undertaking survey work in the surrounding region, so having a new vehicle will be extremely helpful.

OSB: What's next for the Hwange Lion Project/your research?

AL: Long-term biological studies are relatively rare. The Hwange Lion Project has been running for just over 12 years, during which time we have gained a unique insight into the population dynamics and conservation of this particular lion population.

The core of our effort is to maintain the monitoring work and continue to add to this long-term understanding. In addition to this we are continuing undertake research on human-wildlife conflict at the borders of Hwange National Park and this year we will be embarking on some exciting new initiatives to work with local communities to reduce levels of human-lion conflict. In doing so we hope to reduce the number of lions killed by angry herders over loss of domestic stock.

Another exciting component of the project is an initiative to identify and conserve habitat corridors that that link the core Hwange lion population with other regional protected areas. We have already found evidence that these exist and it is important that habitat corridors are recognised and protected in the face of ever expanding human populations.

My other research includes a three-year project, funded by the Darwin Initiative for Biodiversity, on the sustainable management of leopards in Zimbabwe.

- ‹ previous

- 147 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?