Features

Imagine designing and mass-producing nano-sized objects that can interact with molecules and human cells with incredible precision. The structures would be precisely engineered to deliver drug therapies custom-fitted to each patient, or even bind to cancer cells to keep them from reproducing. Imagine being able to deploy a tiny device made of DNA that can detect the presence of a molecule that indicates a major health problem and release a drug.

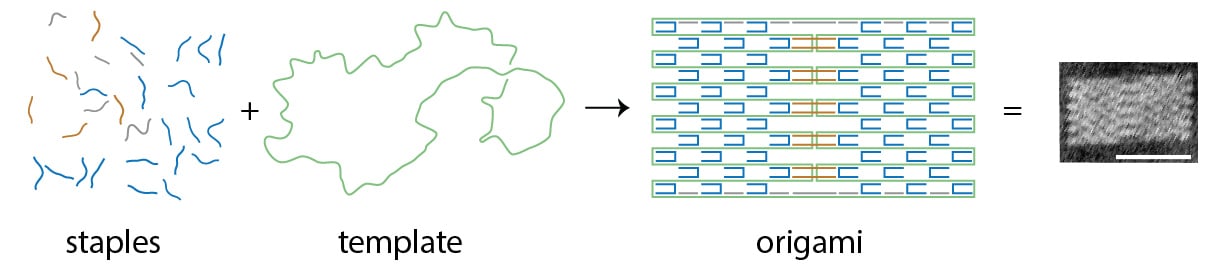

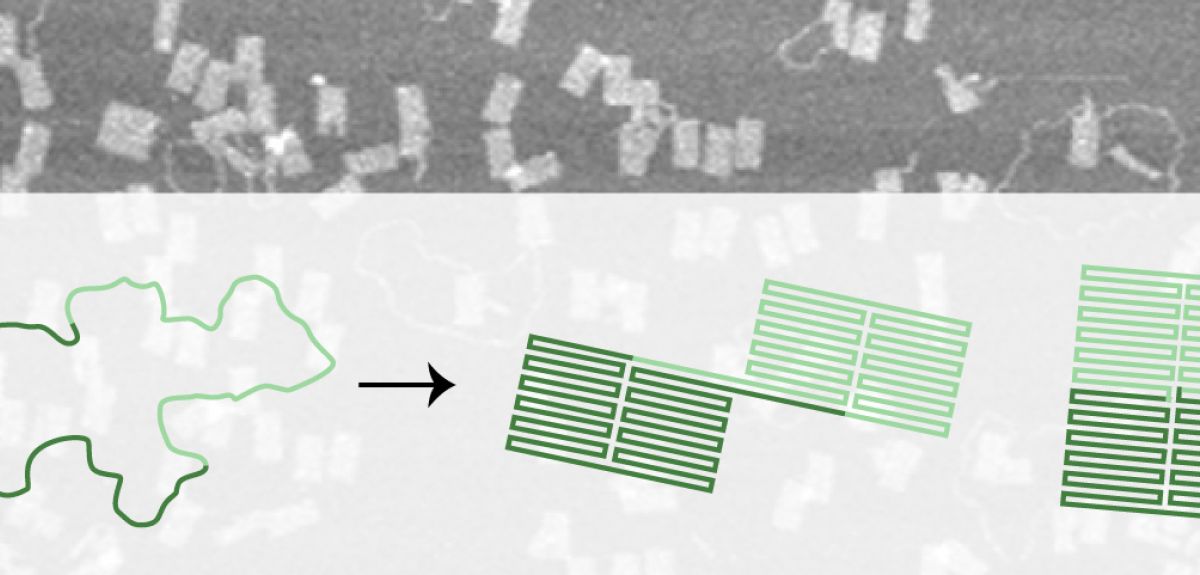

While these sorts of technologies are still a long way off, the process of designing them is advancing rapidly thanks to improvements in DNA origami technique. Nearly ten years ago, researchers first described a technique to fold a long single strand of DNA into various two- and three-dimensional shapes including a smiley face and three-dimensional cubes. The shapes are created by adding multiple small 'staple' strands of DNA to the template strand, gathering and doubling up the strand many times over as the mixture is combined, heated and then cooled in a buffer of salt water. Each drop of stapled DNA mixture contains around 1012 copies of each template strand and staples – if all goes to plan the result is 1012 identical DNA origami shapes. But it doesn’t always turn out that way.

'It is remarkable how well DNA origami works - in fact, it is remarkable that it works at all,' says Jonathan Bath, who is part of the biological physics group in Oxford’s Clarendon Laboratory. 'DNA origami is a reliable technique, if you design a simple structure you can expect a good fraction of your origami to be well-folded but as you increase the complexity of your design (for example when you go from two dimensions to three), the fraction of well-folded origami can fall dramatically.'

The way in which DNA strands and staples combine to form increasingly complex structures can be seen as both predictably obvious and confusing. DNA is a useful construction material because of the predictable way its base pairs join together. Its nucleotide bases Adenine (A), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C), and Thymine (T) form complementary A-T or C-G bonds, which means pairing staple DNA sequences in the right order to match a specific region of the template strand will produce predictable bonds that then produce shapes. Sections that are designed to bind together are given complementary sequences; other sections are given sequences that are as different as possible to minimize unintended interactions. What’s less obvious is how and why the stapled strands fold in sequence into well-formed shapes rather than just collapsing or mis-folding.

'Even the process of creating relatively simple DNA origami shapes produces a certain amount of mis-folded shapes,' Bath notes. 'As DNA origami structures get more sophisticated the technique becomes less reliable, and we end up with more mis-folded or tangled shapes that have to be separated out from the well-folded shapes we want to produce. If we want to fix this then we need to understand the folding. If we can fix it then we can continue to make increasingly sophisticated structures by guiding the folding pathways towards well-folded shapes and steer the system from becoming trapped in mis-folded shapes.'

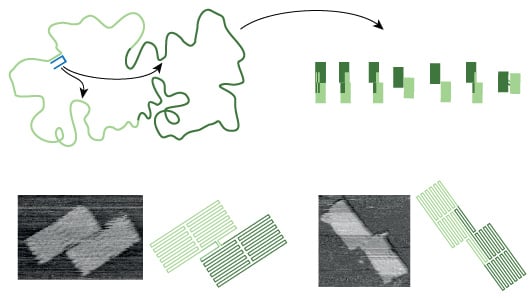

This folding pathway is what Bath and his colleagues have investigated in a paper just published in Nature. Their goal, he emphasises, was not to make a 'new and improved' DNA origami structure but to design a system that would help to understand the mechanism that makes DNA origami fold in the way that it does. 'Often the first step towards understanding a system is to try and break it,' he explains, 'so we designed a DNA origami that has a handful of well folded-shapes but an overwhelmingly large number of misfolded states to trap the system.'

Remarkably, rather than breaking the DNA folding mechanism, Bath’s experiment still produced a surprising number of well-folded shapes. The result, he says, demonstrates the existence of folding pathways that steer the system towards well-folded shapes through a vast folding landscape littered with traps. ‘In any given experiment, we observe a mixture of well-folded shapes, some shapes more abundant than others,’ he explains. ‘The mixture serves as a record of events that take place along the folding pathway, it we tweak the folding pathway then the distribution of shapes that we observe will change.’

The experiment reveals that there are rules that govern the folding of DNA origami – if these rules are incorporated into future designs then they should make the production of complex DNA structures more successful. But the goal of the experiment wasn't just about improving DNA origami structures, but understanding them. 'Simple DNA origami folds well, so from a technology point of view, there is no problem,' says Bath. 'But from a science point of view there is a problem – we do not understand how it works and we would like to understand.'

'For me, the motivation comes from looking at biological systems: they are full of molecular machines –machines that read and copy information, join and break molecules, shuttle cargo from one place to another and so on. At least in principle, there is no reason why we should not be able to build our own machines to tackle similar tasks but this is a tall task and we’ll have to start simple. DNA nanotechnology (of which DNA origami is a subset) offers a realistic route towards the design and construction of molecular machines. If we are serious about achieving those ambitious goals then we need to understand what we are doing.'

The full report in the journal Nature is co-authored by Katherine Dunn, Jon Bath, Andrew Turberfield, Tom Ouldridge, Frits Dannenberg and Marta Kwiatkowska from Oxford University.

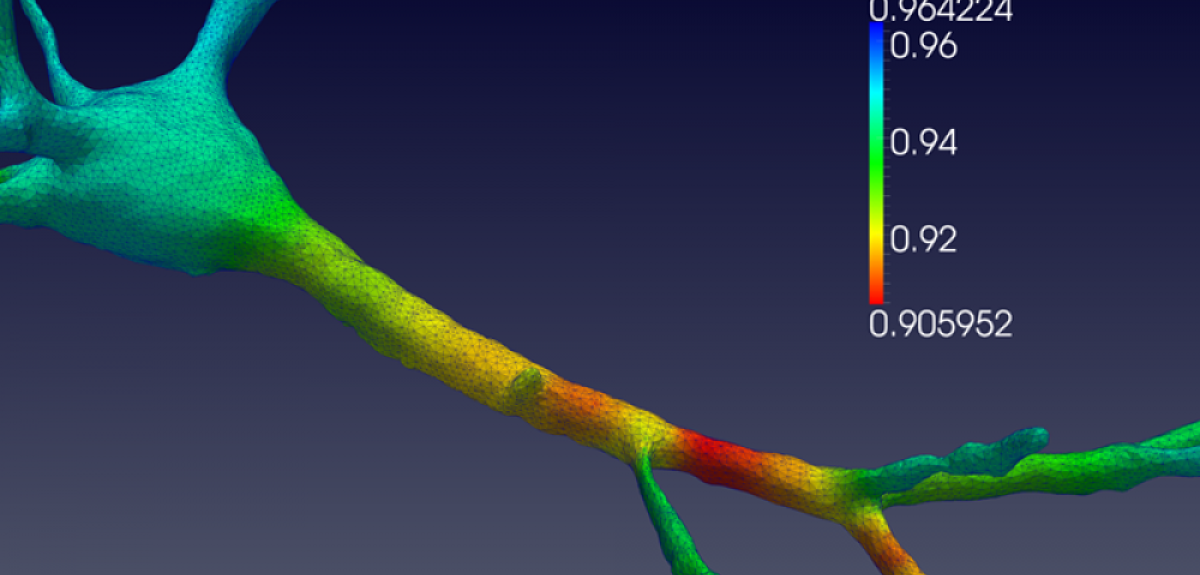

The International Brain Mechanics and Trauma Lab (IBMTL) has been running since the beginning of 2013. Its partnership of 26 academics in 15 locations is not unusual. What is striking is the breadth of disciplines from which they are drawn.

IBMTL doesn’t just bring together the various medical disciplines with an interest in the brain, it includes biologists, physicists, engineers, mathematicians and computer scientists.

The power of the programme is the collaboration of experts from different disciplines to study brain cell and tissue mechanics and how they relate to brain functions, diseases or trauma.

In this video, IBMTL directors Professors Alain Goriely and Antoine Jérusalem explain more about the work of their international collaboration.

Gels are useful: we shave, brush our teeth, and fix our hair with them; in the form of soft contact lenses they can even improve our eyesight.

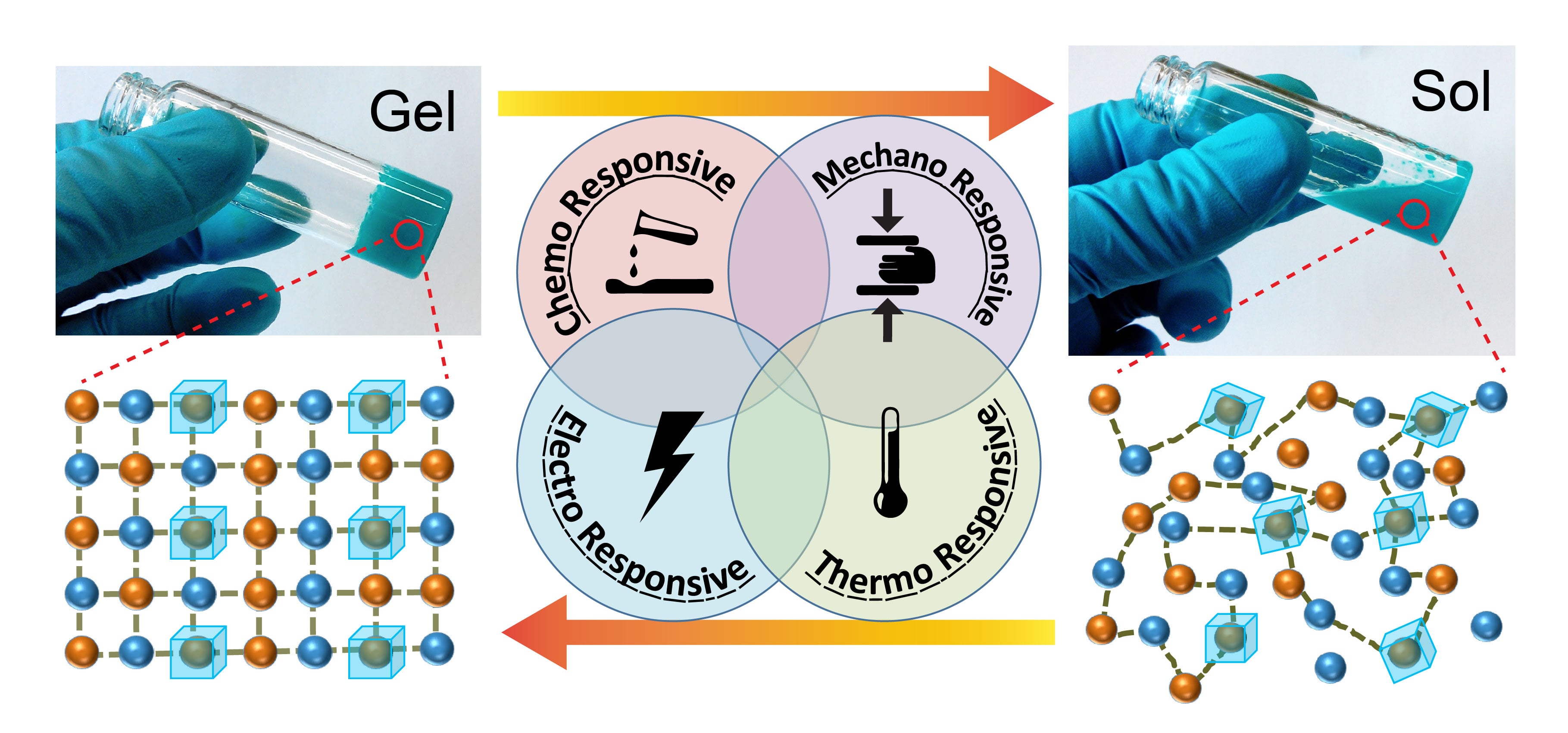

Recently, researchers at Oxford University’s Department of Engineering Science have been investigating ‘smart gels’ that can switch from a stable gel to a liquid suspension of very small particles (a ‘sol’).

Now they report in the journal Advanced Materials that they have discovered a new family of gel-like materials whose behaviour is extremely unusual; not only is their ‘shape-shifting’ from gel to sol entirely reversible but it can be triggered by a range of stimuli including heat, mechanical pressure, and the presence of specific chemicals.

So what makes these new smart gels so smart?

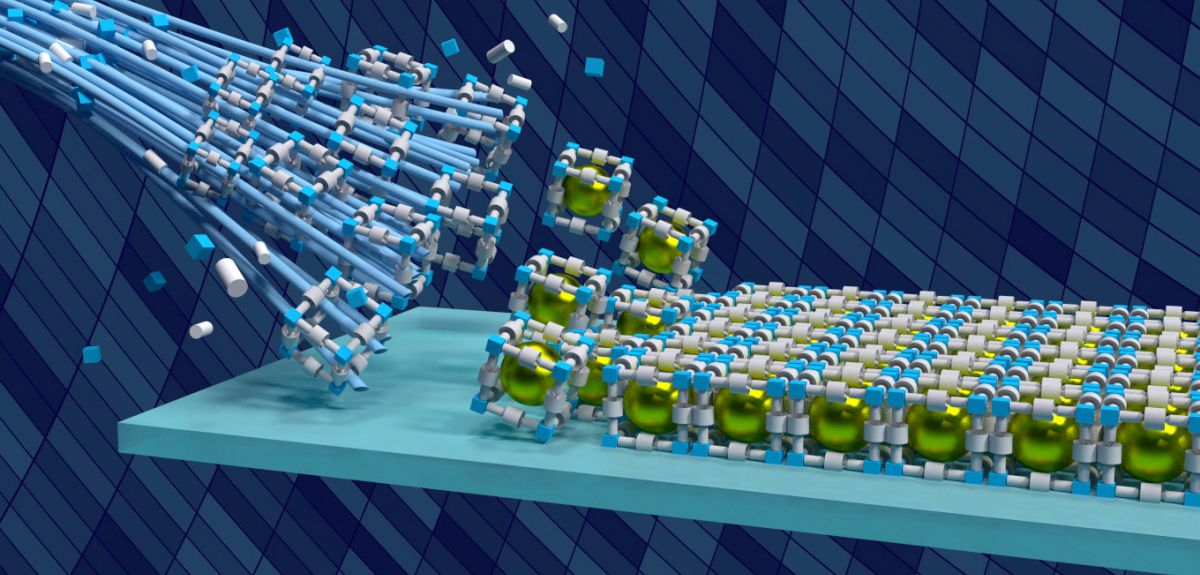

The gels are actually hybrid materials that assemble themselves from metal and organic components, explains Abhijeet Chaudhari, a DPhil student in the Multifunctional Materials & Composites (MMC) Laboratory at Oxford University's Department of Engineering Science, who is the first author of the report.

‘When we scrutinised the hybrid gels under a scanning electron microscope (SEM), we were astounded to see exquisite fine-scale fibre architectures, which are completely different from those known in any other contemporary gel materials,’ Abhijeet tells me.

SEM images (false colour) depicting the intricate gel fibre architecture

SEM images (false colour) depicting the intricate gel fibre architecture

They then discovered that intertwined amongst these microscopic fibres were a profusion of nanoparticles around 100 nanometres in size. An X-ray diffraction technique confirmed that these were nanoparticles of ‘HKUST-1’, a copper-based Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) notable for its very large surface area (exceeding 2000 square-metres in each gram).

Professor Jin-Chong Tan of the Department of Engineering Science, who led the team, says: ‘Because of its fine-scale fibre network architecture, which is hierarchical in nature, the new hybrid gels are remarkably sensitive to different combination of external stimulants.’

Reversible conversion of a hybrid gel subject to physical and chemical stimuli

Reversible conversion of a hybrid gel subject to physical and chemical stimuli

‘This makes this family of hybrid gels highly tuneable, enabling us to engineer bespoke materials with the desired properties to fit a specific application,’ adds Abhijeet.

To illustrate this, the team demonstrated that by simply switching the types of solvent used in material synthesis the electrical conductive properties and mechanical resilience of the gels can be altered.

The tuneable properties of these materials come from the sol-gel transformation in which an apparently stable gel collapses into a sol and then become a gel again once the external stimuli are removed. This behaviour is driven by what is happening inside the material at the microscopic scale where there is rapid molecular bond-breaking (gel to sol) and bond–making (sol to gel).

Jin-Chong says: ‘This fascinating phenomenon is exceptionally rare for gel systems incorporating MOF nanoparticles; to the best of our knowledge this is the first example of its kind reported in the literature.’

Such shape-shifting materials could find applications in Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS) and NEMS devices. They could also create ‘self-healing’ coatings that can repair themselves after impact or corrosion damage or in energy technology to build new electrolytes for rechargeable batteries or enhanced dielectrics for supercapacitors.

But it’s the promise of MOF nanoparticles suitable to make into thin films for sensors and microelectronics that is particularly alluring.

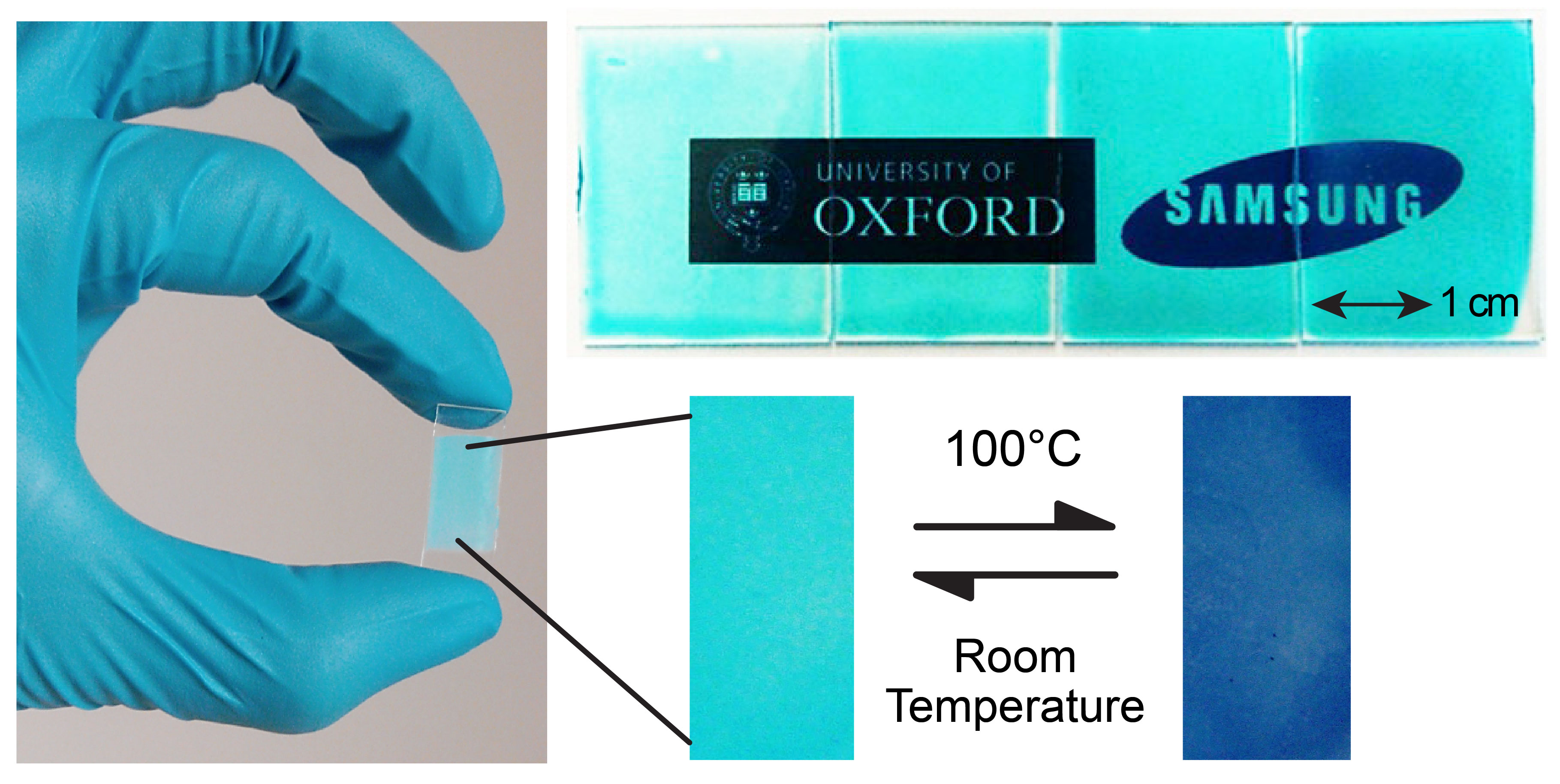

Abhijeet explains that conventional methods of MOF thin film fabrication are costly, laborious, and mostly limited to creating small surface areas, making them unsuitable for large-scale commercial use: ‘We discovered that copious amounts of high-quality HKUST-1 (MOF) nanoparticles can be straightforwardly harvested by breaking down the gel fibres using methanol.’

‘These MOF nanoparticles can then be used as a ‘precursor’, making it easy to fabricate multifunctional thin films on various substrates. These thin films can, for instance, function as a coupled temperature-moisture sensor that rapidly switches from turquoise to dark blue colour for easy identification, reversibly, upon heating.’

Thin film sensors created using MOF nanoparticles harvested from hybrid gels

Thin film sensors created using MOF nanoparticles harvested from hybrid gels

The team worked with Isis Innovation to patent the technology and Samsung Electronics, who part-funded the research, are looking to translate this discovery into a range of real-world applications including optoelectronics, thin-film sensors, and microelectronics.

‘We believe our method has huge potential,’ comments Jin-Chong, ‘it opens the door to exploiting MOF-based supramolecular gels as a new 3D scaffolding material useful for engineering optoelectronics and innovative micromechanical devices.’

In the future, it seems, smart gels could lead to some very smart technology.

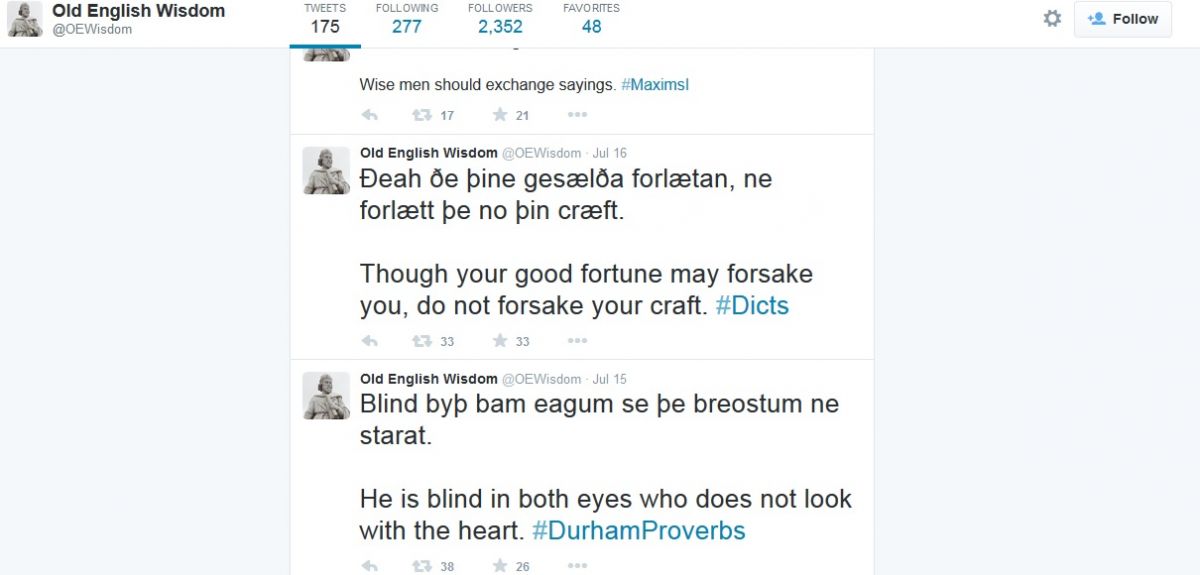

An expert in Old English at Oxford is sharing Anglo-Saxon wisdom on Twitter – and the pithy thousand-year-old advice is proving popular with a new audience.

Dr Eleanor Parker, a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow based at TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, studies literature produced in England during the eleventh and twelfth centuries and teaches Old English and Old Norse.

She began tweeting lines from Anglo-Saxon literature in May and has since picked up a loyal following of nearly 2,500 people.

Dr Parker says: 'I'm intrigued by how well this ancient tradition seems to work within the brand-new medium of Twitter, when they are (except in their fondness for brevity) almost exact opposites: Twitter thrives on the knee-jerk reaction and the swift reply, while wisdom literature is a genre which grows slowly, out of years, lifetimes, and centuries of human experience.

'But what medium and message have in common is the idea that something of value deserves to be shared: Gleawe men sceolon gieddum wrixlan, one poem famously says, "Wise men should exchange sayings".'

Dr Parker has quoted from sources including Beowulf, Alfred the Great, and a collection of proverbs held in Durham Cathedral.

'Some of the texts I'm quoting from are dedicated collections of proverbs and maxims, in poetry or prose, while some are single instances from longer texts; some are translations or versions of Latin texts, others have no known source; some are paralleled in later medieval English proverbs, some in other languages such as Old Norse,' she says.

'Some are so culturally specific that they may seem to offer nothing more to a modern audience than a historical curiosity. But others have much to say about subjects which are timeless: friendship, love and family; the right and wrong ways to use speech, strength, skill or knowledge; how to teach and how to learn; the experience of grief, loneliness, joy, and companionship; the value of patience, self-restraint, loyalty, and a generous heart.

'They celebrate both the riches which can be learned from books and the wisdom which can be earned through the simple act of living.'

Some of the proverbs are timeless pieces of advice which would not look out of place in a modern newspaper's 'Agony Aunt' column. The following come from the Durham Proverbs in Durham Cathedral:

Geþyld byþ middes eades.

Patience is half of happiness.

Æt þearfe mann sceal freonda to cunnian.

In time of need, a man finds out his friends.

Ne sceal man to ær forht ne to ær fægen.

One should not be too soon fearful nor too soon joyful.

Seo nydþearf feala læreð.

Necessity teaches many things.

Hwon gelpeð, se þe wide siþað.

Little boasts the one who travels widely.

But not all are as easy to apply in the 21st Century…

Ne mæg man muþ fulne melewes habban and eac fyr blawan.

No one can have a mouth full of flour and also blow on a fire.

Nu hit ys on swines dome, cwæð se ceorl sæt on eoferes hricge.

It's up to the pig now, said the man sat on the boar’s back.

Readers can follow @OEWisdom on Twitter and read more about the project on Dr Parker’s blog.

Why are men more aggressive than women?

There are two competing theories. However, a study by Oxford University researchers has found that both may actually be right.

Doctor Ralf Wölfer is part of the Department of Experimental Psychology. He recently published the results of a study across schools in three European countries, which mapped networks of aggression to see what they could tell us about differences between boys and girls.

I asked Ralf about the theories and how his research is bringing them together.

OxSciBlog: First of all, what are the two theories?

Ralf Wölfer: The two theories are sexual-selection theory and social-role theory. They’re really the competing sides of the nature-nurture debate. Sexual-selection theory says that males are competing for reproductive success, so are more aggressive generally and especially to other males. It’s human nature.

Social-role theory says that differences are sociological, based on traditional divisions of labour. Socialisation shapes gender specific identities, expectations and behaviour. So it’s nurture – how we’re brought up.

Traditionally, the two theories have been seen as competing. I’m not the first to use both theories – there have already been others saying we should consider both. But this paper took an empirical approach.

OxSciBlog: What was that approach?

Ralf Wölfer: We wanted to look at intra-sex and inter-sex aggression in a given environment. To avoid confusion, it might help to think of these as same-sex aggression and other-sex aggression.

We used detailed social network analysis to disentangle aggression across almost 600 social networks in different environments – teenagers in school classes for this study. We were able to score these environments for same-sex and other-sex aggression.

We hypothesised that a dual-theory approach, with sexual-selection theory explaining same-sex aggression and social-role theory explaining other-sex aggression, was better than applying just one.

For that dual-theory approach to be valid, we were testing two hypotheses:

Firstly, that males are more aggressive than females to same-sex individuals, and also more aggressive to other-sex individuals.

Secondly, that predictors derived from sexual-selection theory would explain differences between males and females in same-sex aggression whereas predictors derived from social-role theory would explain differences in other-sex aggression.

OxSciBlog: So what were these predictors?

Ralf Wölfer: For example, for social-role theory, you would expect boys in those groups with more traditional beliefs about masculinity to exhibit more other-sex aggression. For sexual-selection theory, you would expect to see more aggression in groups with a higher proportion of males to females, as there’s more competition among the boys.

Once we had the scores from the social network analysis we applied predictors from the two theories to see how well they could explain the differences in those scores.

OxSciBlog: How did you do the social network analysis?

Ralf Wölfer: This is one thing that was a useful lesson from the study design. Usually social network analysis is used to map friendship networks – positive relationships. In this case, the study used it to map a negative network of aggression. What we found is that it worked well when applied in this way.

The participants were from the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal survey in Four European Countries, a group that contained more than 10,000 students in nearly 600 classes. Each of those classes is a separate environment that can be compared with the others.

The study group was originally set up to compare children of immigrant and non-immigrant populations so there was a high proportion of students from ethnic minority groups. Many have parents from Turkey, Iraq and Morocco. That was important because we could look beyond a purely western European sample to a more varied group.

We then asked each student to nominate aggressors. Mapping aggression has often been done by self-reporting but we chose to use peer reporting as we felt it would be more accurate. We asked ‘who is sometimes mean to you?’

|

| Sample aggression network of a school class. Black circles represent boys, and white triangles represent girls. Arrows indicate aggression nominations, with the direction of the arrow indicating the person nominated as an aggressor and the start of the arrow indicating the nominator. |

By counting nominations from boys and girls for each individual, we could give them a same-sex aggression score and an other-sex aggression score. Then we could determine an average same-sex aggression score and other-sex aggression score for each class.

As expected, on average males were more aggressive to both sexes although there were some classes where females were more aggressive.

OxSciBlog: When explaining these aggression scores, what did the results show?

Ralf Wölfer: They showed that our dual-theory hypothesis was right!

We found that sexual-selection theory explained differences in same-sex aggression. For example, those classes with a higher proportion of boys to girls saw more male-male aggression, while classes with a higher proportion of females or with a more equal social structure saw less male-male aggression.

Social-role theory explained differences in other-sex aggression. For example, classes with more traditional views of gender roles saw more male-female aggression, while classes with less traditional gender norms saw less male-female aggression.

OxSciBlog: In the end, what does that mean?

Ralf Wölfer: It is empirical evidence to confirm that we need to consider both biological and social explanations for aggression. Sexual-selection and social-role theory are both necessary. It is also important to differentiate between same-sex/intra-sex and other-sex/inter-sex aggression as the roots of each may be different. One way to do this is to use aggression networks, as demonstrated in this study.

- ‹ previous

- 146 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?