Features

In 2012 CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) discovered the Higgs boson, the 'missing piece' in the jigsaw of particles predicted by the Standard Model.

Last month, after two years of preparation, the LHC began smashing its proton beams together at 13 Trillion electron Volts (TeV), close to double the energy achieved during its first run.

'We do not know what we will find next and that makes the new run even more exciting,' Daniela Bortoletto of Oxford University's Department of Physics, a member of the team running the LHC’s ATLAS experiment, tells me. 'We hope to finally find some cracks in the Standard Model as there are many questions about our universe that it does not answer.'

One of the big questions concerns dark matter, the invisible 'stuff' that astrophysicists estimate makes up over 80% of the mass of the Universe. As yet nobody has identified particles of dark matter although physicists think it could be the lightest supersymmetric (SUSY) particle.

'In the new run, because of the highest-ever energies available at the LHC, we might finally create dark matter in the laboratory,' says Daniela. 'If dark matter is the lightest SUSY particle than we might discover many other SUSY particles, since SUSY predicts that every Standard Model particle has a SUSY counterpart.'

Then there's the puzzle of antimatter: in the early Universe matter and antimatter were created in equal quantities but now matter dominates the Universe.

'We still do not know what caused the emergence of this asymmetry,' Daniela explains. 'We have finally discovered the Higgs boson: this special particle, a particle that does not carry any spin, might decay to dark matter particles and may even explain why the Universe is matter dominated.'

Discovering the Higgs boson was a huge achievement but now the race is on to understand it: a prospect that Daniela is particularly excited about.

'This particle is truly fascinating,' she says. 'Spin explains the behaviour of elementary particles: matter particles like the electron have spin 1/2 while force particles like the photon, which is responsible for the electromagnetic interaction, have spin 1. Spin 1/2 particles obey the Pauli principle that forbids electrons to be in the same quantum state.

'The Higgs is the first spin 0 particle, or as particle physicists would say the first 'scalar particle' we've found, so the Higgs is neither matter nor force.'

Because of its nature the Higgs could have an impact on cosmic inflation and the energy of a vacuum as well as explaining the mass of elementary particles.

Daniela tells me: 'Because of the Higgs the electron has mass, atoms can be formed, and we exist. But why do elementary particles have such difference masses? The data of run 2 will enable us to study, with higher precision, the decays of the Higgs boson and directly measure the coupling of the Higgs to quarks. It will also enable us to search for other particles similar to the Higgs and determine if the Higgs decays to dark matter.'

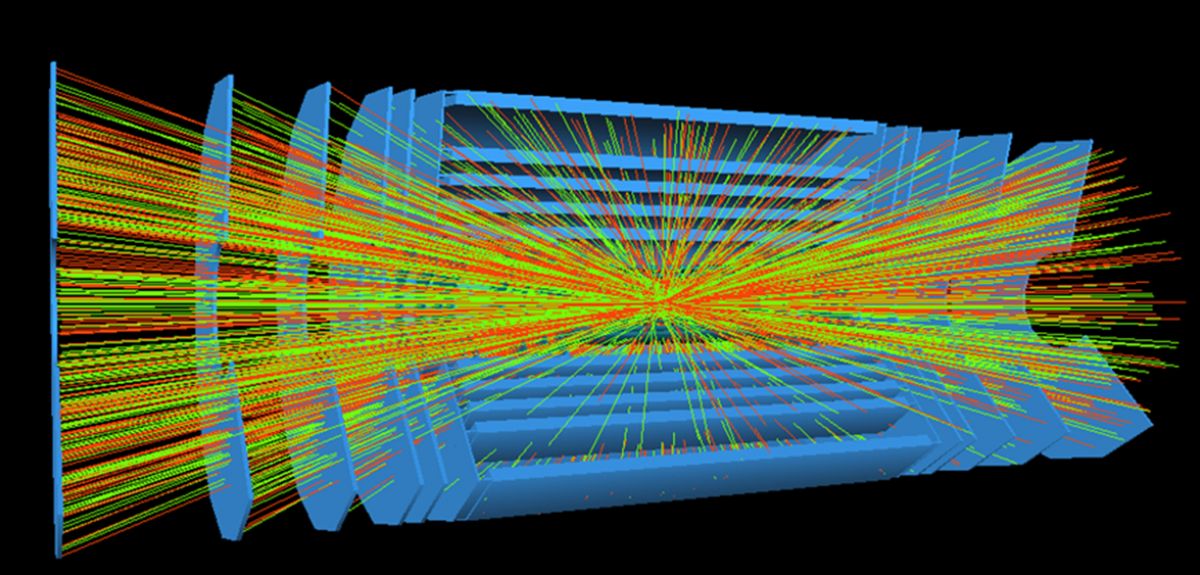

Daniela is one of 13 academics at Oxford working on ATLAS supported by a team of postdoctoral fellows, postgraduate students and engineering, technical, and computing teams. The Oxford group plays a lead role in operating the SemiConductor Tracker (SCT), most of which was assembled in an Oxford lab. This provides information on the trajectories of the particles produced when the LHC’s beams collide, which was crucial to the discovery of the Higgs boson.

Whilst the next few years will see the Oxford group busy with research that exploits the LHC’s new high-energy run, the team are also looking ahead to 2025 when the intensity or 'luminosity' of the beams will be increased.

The LHC is filled with 1,380 bunches of protons each containing almost a billion protons and colliding 40 million times per second. This means that every time two bunches of protons cross they generate not one collision but many, an effect called 'pile-up'.

'After this luminosity upgrade the LHC will operate at collision rates five to ten times higher than it does at present,' Daniela explains. 'In run 1 of the LHC we had a maximum of 37 pile-up collisions per crossing but with the upgrade to the High Luminosity LHC, or 'HL-LHC', this will increase to an average of 140 pile-up events in each bunch crossing.'

With the HL-LHC generating many more collisions, the international Oxford-led team are designing and prototyping parts of a new semiconductor tracker that will be needed to help reconstruct particles from the complex web of decay trails they leave inside the machine.

As the LHC ramps up both its energy and luminosity it promises to give scientists working on experiments such as ATLAS answers to some of the biggest questions in physics. One thing is certain: this new physics will also lead to a whole set of new questions about the matter that makes up us and the Universe around us.

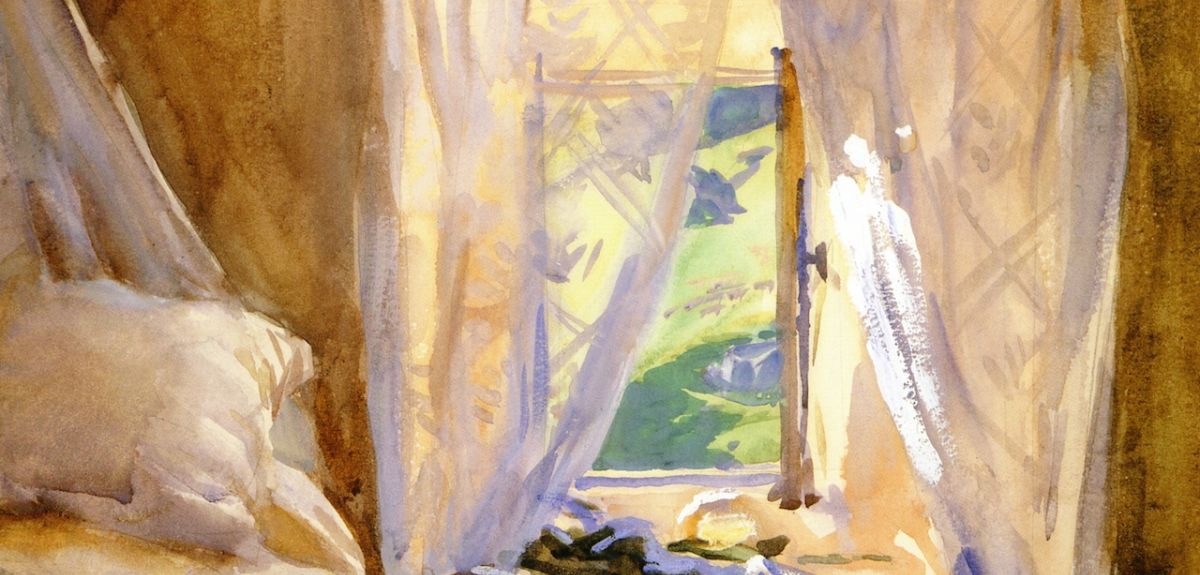

Jackson Pollock, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, John Singer Sargent. American artists have produced some of the most popular works of art in galleries across the world.

But to date the subject has been 'largely absent' from Oxford’s research and teaching programmes, according to the Head of the History of Art Department.

'Oxford is arguably the most important centre for the study of American history, politics, and culture outside North America,’ says Professor Geraldine A. Johnson. ‘Until now, however, American art has largely been absent from the University’s research and teaching programmes.'

This is due to change with the establishment of two one-year Visiting Professorships for scholars of American art.

In 2016/17 and 2017/18 the visiting professors will help to establish American art from the colonial period onwards as a new field of study for Oxford Master's students in Art History, introduce the visual arts of the United States to undergraduate students in History and Art History, and provide new global perspectives on American art to scholars and curators in Oxford and beyond.

'The Terra Foundation for American Art Visiting Professorships at the University of Oxford will allow the study of the visual culture of the United States to become a key component of Oxford’s world-class American studies agenda,' says Professor Johnson.

'We also hope that these posts will allow new initiatives to be developed in collaboration with the University’s museums and collections.'

The visiting professorships have been established by the Terra Foundation for American Art, which describes its mission as 'fostering exploration, understanding, and enjoyment of the visual arts of the United States for national and international audiences'.

The Ashmolean Museum has raised the money needed to acquire an iconic painting of Oxford’s High Street by JMW Turner.

The Museum launched a public appeal in June to acquire the painting of 1810 called The High Street, Oxford.

The painting was offered to the nation in lieu of inheritance tax, meaning the Museum needed to raise only £860,000 to acquire it. Grants of £550,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund, £220,000 from the Art Fund and £30,000 from the Friends and Patrons of the Ashmolean meant that £60,000 was required. Local people and museum visitors exceeded this target in only four weeks.

'The Museum has been overwhelmed by public support,' says Dr Alexander Sturgis, Director of the Ashmolean.

'With well over 800 people contributing to the appeal, it is clear that the local community, as well as visitors to the Museum from across the world, feel that this picture, the greatest painting of the city ever made, must remain on show in a public museum in Oxford.'

The Museum plans to lend the painting to regional museums so as many people as possible will be able to see it. The painting will also be at the heart of a new series of educational activities for schools and young people, and it will be part of the Museum’s Nineteenth Century Gallery which will be refurbished and reopened in early 2016.

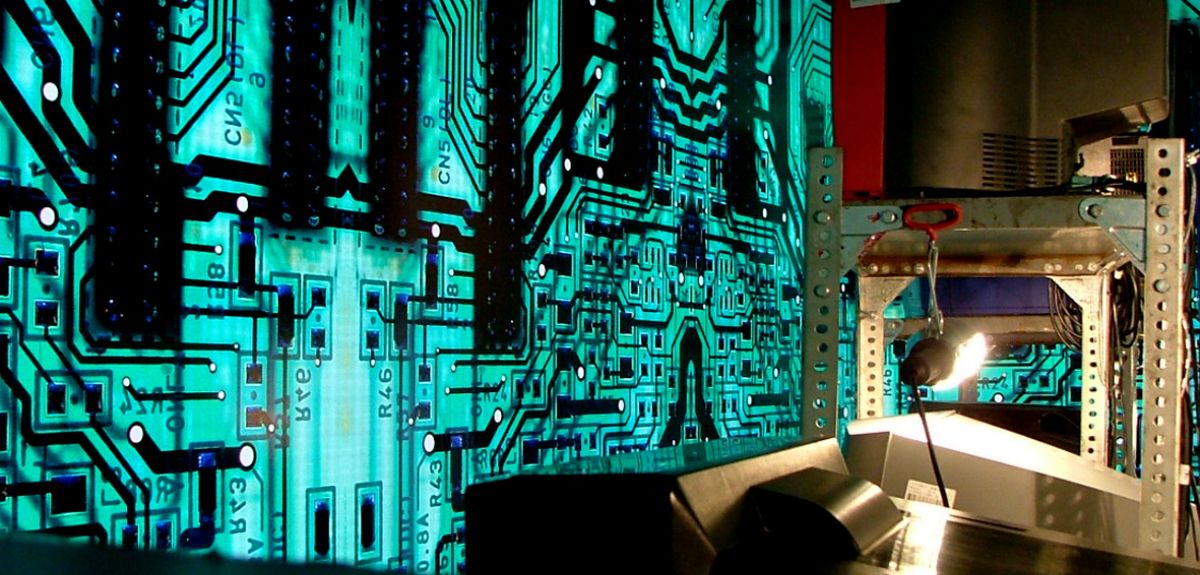

The Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge University are to receive a £1m grant for policy and technical research into the development of machine intelligence.

The grant is from the Future of Life Institute in Boston, USA, and has been funded by the Open Philanthropy Project and Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors and Space X.

This grant will allow Oxford University's Future of Humanity Institute, part of the Oxford Martin School and Faculty of Philosophy at the University, to become the world’s largest research institute working on technical and policy responses to the long-term prospect of smarter-than-human artificial intelligence.

This growth follows the Institute Director Professor Nick Bostrom's bestselling book “Superintelligence”, which was endorsed by both Elon Musk and Bill Gates.

Professor Bostrom said: 'There has much talk recently about the future of AI. Elon - characteristically - decided to actually do something about it.

'This grant will enable Oxford to expand its research in this area, forming the largest group in the world of computer scientists, mathematicians, philosophers, and policy analysts working together to ensure to that advances in machine intelligence will benefit all of society.'

The funding is part of an international grant programme dedicated to “keeping AI robust and beneficial”, which today awarded nearly $7m. The programme had nearly 300 applicants this round, which were subject to a thorough academic review process. The joint Oxford-Cambridge research centre will be the programme’s largest grant. Three other Oxford-based projects also received funding.

Andrew Snyder-Beattie of the Future of Humanity Institute said: 'The joint centre between Oxford and Cambridge universities will allow a team of computer scientists, mathematicians, philosophers, and policy analysts to collaborate and help ensure that advances in machine intelligence will benefit all of society.'

Teachers, linguists and academics will discuss the state of the English language at a one-day symposium today.

The symposium, called English Grammar Day, has been organised by Oxford University and UCL, and takes place at the British Library.

Professor Charlotte Brewer of the Faculty of English Language and Literature at the University of Oxford, who co-organised the event, said: "The National Curriculum now tests schoolchildren on English grammar, but sometimes these tests are at odds with how people actually speak. Part of the reason we organised this event is to support teachers as they implement the National Curriculum."

Changes in the English language have been criticised for hundreds of years, and certain features are often singled out as a sign of declining education, social standards or politeness.

"Language change is absolutely natural, as any linguist will tell you," said Professor Brewer. "But people often feel acute anxiety about these changes. For example, in the 1930s, the word 'finalise' was hotly debated on both sides of the Atlantic. Nowadays we would consider it standard English. Grammarians and lexicographers have to keep pace with this rate of change, by maintaining corpuses of English as it is really used."

Professor Brewer will give a talk called Monarchs and minnows vs. broadband and bungee jumping: what is the job of a children’s dictionary?, in which she will discuss recent research from Oxford University Press that shows how children's vocabulary has changed over the years, reflecting new technology and pop culture phenomena.

"It's good news that children innovate with language in this way," said Professor Brewer. "People's anxiety about language change often seems to reflect a generation gap: they're worried that children won't learn to 'speak properly'.

"But the test of speaking properly is if we're communicating what we want to communicate, which might mean speaking in one way with your friends, and another way with your parents or teachers. And all children learn to do this.

"Everybody uses language which identifies you as part of a social group, and everyone 'code-switches' in this way. Dictionaries and grammar books aim to describe the English language as it is used, rather than prescribing a particular way that it ought to be used."

- ‹ previous

- 148 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?