Features

The EU’s trade deal with Canada was held up after objections from Belgium’s French-speaking Walloons last week. The Ceta pact was eventually signed after a week of talks.

Martin Conway, Professor of Contemporary European History, tells us more about the group which has suddenly been thrust into the international spotlight:

Europe, it seems, has been looking in the wrong place to understand its malaise. At different points in the past couple of years, the Poles, the Hungarians and, of course, the British have been singled out as the principal internal opponents of the European project. But now it appears that the real obstacle lay closer to the home of the European institutions in Brussels.

By opposing CETA, Europe’s proposed free trade treaty with Canada, the predominantly French-speaking Belgian region of Wallonia has rather abruptly vaulted itself into the centre of European political debate. Its Socialist Party political leaders have become the unexpected focus of international attention by refusing to give their consent to the deal. And without the agreement of all regional parliaments, Belgium’s national government cannot give its consent to CETA at the EU level.

Life in Wallonia

Namur – the location of the Walloon parliament and government of southern Belgium – makes for an unlikely heartland of insurrection. Its imposing citadel did indeed see service twice in the 20th century in unsuccessful attempts to hold up German invaders, but it is predominantly a peaceful town. It was chosen for its governmental role principally because it was not one of the more obvious candidates for the capital of Wallonia.

There is much about the idea of a Walloon region, and its pretentions to some form of mini-statehood, which lends itself to a certain satire. An unnamed European Socialist leader even referred to it dismissively as an Asterix village.

There has long been a Walloon movement, and putative identity – initially cultural, but by the mid-20th century somewhat more political – but the principal logics of Walloon sentiment have always been negative. Opposition to the perceived arrogance of the governments in Brussels and, in more recent decades, to the dominant influence of Flanders and of the Dutch-speaking majority within the Belgian state, has generated an increasingly bitter sense of the Walloons as a disadvantaged minority.

They see their interests as being neglected by political elites and feel they live on the front line of the economic suffering and social fragmentation generated by the decline of the traditional heavy industries of the region.

There is plenty of logic to this mentality. Travel a short distance west or east from Namur to the post-industrial conurbations of Charleroi or Liège, and one enters a world which feels very different from the European institutions of Brussels.

These are the places where the industrial revolution initially established itself on the continent of Europe, but which have been caught up for more than 50 years in the intersecting processes of the decline of heavy industry and the dislocation of urban communities. The familiar symptoms are all here – drug use, family breakdown, criminality, social marginality and the erosion of public services.

This is the world where the former Socialist mayor of Liège, André Cools, could be murdered in an obscure gangland killing in 1991, and where Marc Dutroux could commit with impunity his vile abduction and incarceration of a number of young girls in the 1990s. To say that the Walloons have a fairly low estimation of their rulers risks being a serious understatement.

Walloon politics

The Socialist Party (PS) has dominated as the defender of the region’s interests since it adopted an emphatically regionalist mentality in the 1970s. It skilfully combined opposition to a hostile external world with the force of municipal and institutional patronage closer to home.

But recent events have placed the PS under pressure. At a national level, the results of the last federal elections led to the departure of the Socialists from the national government. A Flemish-dominated administration took over, in which the leading voice is that of the neo-liberal N-VA party.

Cuts to state budgets, combined with none-too-subtle comments from Bart De Wever, the populist leader of the N-VA, about the dependence of the Walloons on welfare handouts, have raised the political temperature in Wallonia.

At the same time, space has been opened up for an extreme-left rival to the PS, the Parti du Travail de Belgique (PTB), to build its support. Even by Europe’s contemporary standards, the PTB is a remarkable phenomenon. Established by a group of Flemish students in the 1970s, its still-dominant founding figures could variously be described as Maoist or radical Communist. They reject the lure of centrist alliances in favour of a radical third worldism.

More immediately, the PTB’s ability to give a voice to the marginalised communities of industrial Wallonia has enabled the party to build a basis in the town halls of the region. It has also given an energy to the campaign against the free trade treaty as part and parcel of its rejection of capitalist globalisation.

None of this means that a Walloon revolution is nigh – but Belgian politicians, both local and national, know better than to underestimate the radical potential of Wallonia. After 1945, it was the Walloons who mobilised to force the Belgian king Leopold III to abdicate for the twin crimes of sympathising with German occupiers and choosing a Flemish second wife. And in the latter decades of the 20th century, numerous strikes obliged the Brussels government to make timely concessions to Walloon demands.

Even so, the head of the Walloon government, the Socialist Paul Magnette, has an astute sense of the politically possible. He has avoided tying himself too closely to opposition to the Canada trade deal. Rather, he has sought further clarifications and concessions. And even if the government in Brussels failed to forestall this crisis by listening to Walloon demands, Magnette has interlocutors elsewhere who know all about Wallonia and its sensitivities.

Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, is a Luxembourgish Christian Democrat from the other end of the Ardennes, while Martin Schulz, president of the European Parliament, is a Socialist from a town close to Aachen in western Germany, almost within sight of Wallonia. These are men who understand the balance in the politics of the Low Countries between political brinkmanship and timely concessions. All, one suspects, will be settled in due course.

The future is Walloon

But even if this crisis seems likely to prove short-lived, it does prove two wider truths about contemporary Europe. The first is that national governments are often no longer sovereign.

The project of European unity was built not on the erosion of national state authority, but on the privileging of it. It was national leaders who, established in the European Council from the 1960s onwards, made the crucial decisions about Europe. They traded national interests in a complex game of give and take.

However, nation states are now much more complex institutions. Nobody quite understood when they devolved responsibility for international commerce from the national government to the regions in Belgium, what the consequences might be. In this CETA debacle, we are seeing them in action.

The other regions of Europe, from Catalonia to Scotland, will all be observing events in Wallonia and pondering their own roles. What, Nicola Sturgeon must be thinking, could a local administration gain from blocking a national trade deal, especially as Brexit looms?

The Walloon crisis also demonstrates once again that there is no majority in Europe for what used to be called political common sense. The origins of CETA go back seven years. It was devised in an era when political leaders could believe that free trade was one of the constituent elements of economic progress.

Since then, the economic crisis, the travails of the euro, and the destructive impacts of globalisation have blown that logic apart. Free trade – and its liberal corollary, the free movement of people – have lost their mass appeal. Nowhere is that more true than in Wallonia. It will take more than a late night compromise among political elites to put that back together again.'

Professor Conway wrote this piece for The Conversation.

Last week, the ‘Jungle’ camp for migrants in Calais was cleared by the French authorities.

Earlier this year, Oxford historian Professor Peter Frankopan visited the camp as part of a team of cricket-loving writers called Authors CC.

While he was there, he played cricket with young men from Afghanistan who lived in the Jungle.

In an article for the Financial Times, and below, he describes the experience:

‘As we arrive, a group of smiling Sudanese teenagers approach us, one of them wearing an “I Love London” sweatshirt. They recognise the stumps and bats we have brought with us and say that, while they have watched several games, they could not make head or tail of the rules.

It is the Afghans we want, they tell us, pointing us towards the Youth Club, where the young have activities laid on for them by other refugees, who have taken on the responsibility of looking after each other.

Immediately we are surrounded by boys who take turns swishing the bats around to get a sense of their weight and balance before demonstrating the sort of textbook forward defensive drives that would have connoisseurs of the game cooing in admiration.

We head out across the wasteland towards the steep incline leading up to the motorway that leads to the Channel tunnel, which is protected by three-metre-high fences. We set out the stumps on a worn road, and the Afghans huddle around to agree on where a marker should be placed to indicate when a wide ball has been bowled. It is an example of how seriously they take the idea of fair play.

Two dozen or so have caught wind of the unscheduled match about to take place and come to join in. They are divided into two teams by captains that the Afghans appoint among themselves, with members of Authors CC split up to balance. They used to talk about day-night one-day internationals as pyjama cricket, because of the bright colours the teams wore.

Here is the real thing: players dressed in a motley collection of T-shirts (including an Italian football shirt), poorly fitting trousers and — in the case of the opening bowlers, who were about as fast as any I’ve ever faced — flip-flops. As the game gets going, the captains repeatedly break off to consult on whether the ball has crossed the (notional) boundary line, and to double-check the score — being kept all the while by a 16-year-old umpire, who tells me as I go to bat that we require 10 off the last over (this time, I do manage to hit what we need).

I speak with my new teammates about their journeys across Iran and Turkey, about how they had been treated in Europe. Above all, I ask why they want to come to the UK. “Because England is fair and open,” one of them tells me; “because of the education”, “because the English are good people — like you, my friend”, come the replies.

It makes me think. On October 14, 1914, Britain allowed in 16,000 Belgian refugees, feeding, looking after and resettling them. In other words, nearly twice the population of the Jungle in a single day. Those were different times, of course, and the UK was on a different trajectory than it is today.

But I was stumped when I was asked why we would not at least allow the children to come to our country. “We are trying to work it out,” I said, rather unconvincingly. “I hope we will see you soon,” one young chap said as we left; “I will get you out next time.” He does not appear to have been one of the 14 unaccompanied minors allowed in this week; but I will be ready if and when he makes it.'

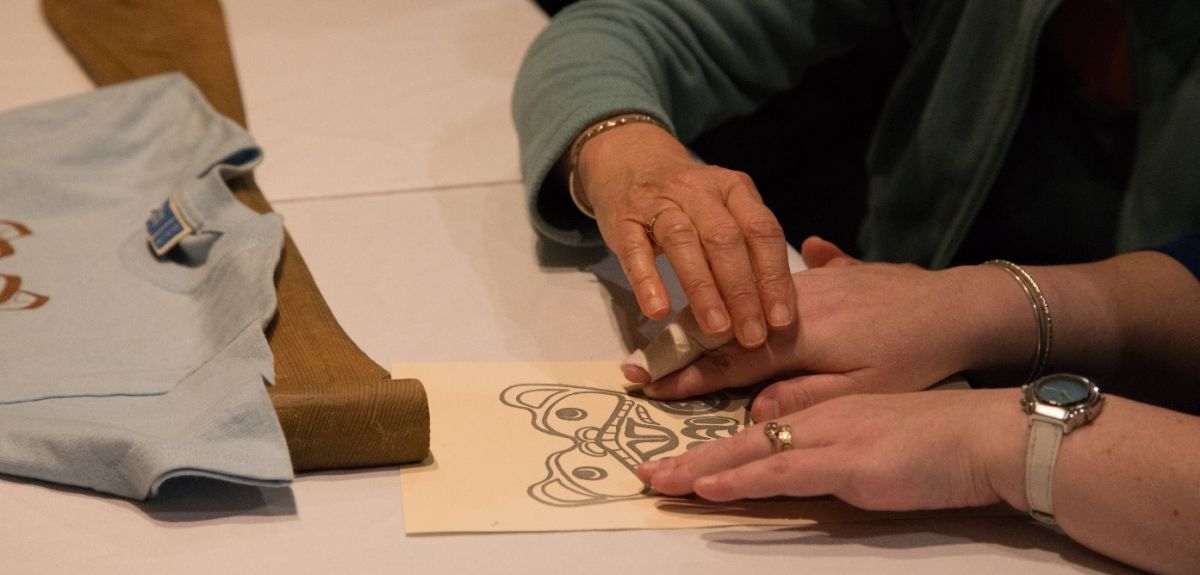

A new joint project between the Oxford e-Research Centre and Oxford University Museums will develop multisensory tools to help enable blind or partially sighted people (BPSP) to engage in a more accessible and meaningful way with the collections in Oxford University's museums.

The project, which began in September 2016, is working with local BPSP communities to help develop the tools.

With about two million people registered blind or partially sighted in the UK, this project could greatly improve the museum experience for a lot of people.

‘I get really frustrated when I go to a museum and there’s no way to experience it,’ says Mrs Pamphilon, who runs a social group for visually impaired people in Oxfordshire. ‘Having things you can touch and feel just opens up a new world.’

To tackle this issue, museums internationally are experimenting with solutions to improve BPSP access to 2D and fragile 3D art (for example a recent exhibition in Spain's Prado Museum which invited blind and partially sighted people to touch specially-created copies of works by masters such as El Greco and Francisco Goya).

The 18 month collaboration, funded by the University's IT Innovation Fund (now IT Innovation Challenges), aims to further develop the touch tile approach, using techniques such as 3D printing to improve the touch elements of the tile, and using cheap and simple technology such as Raspberry Pi to deliver pre-recorded audio descriptions.

This should decrease the cost to museums of giving BPSP an experience more akin to that of the majority of museum visitors, and therefore increase availability and accessibility for BPS visitors.

The aim is to allow BPSP visitors to engage with both 2D and 3D artworks intuitively, dipping in and out and being able to select the part of the audio description they are interested in (rather than being restricted to a fixed linear recording).

Susan Griffiths, Community Engagement Officer at Oxford University Museums, says, "Our aim is to create a tool that can allow blind and partially sighted people to independently engage with some of the world famous visual arts held by the Oxford University Museums, in particular the Ashmolean.’

Strand one of the project, led by the Museums with support from Dr Torø Graven (Department of Experimental Psychology), will focus on understanding the tactile sensations that can be used to assist BPSP to experience the tiles (e.g. line fineness, texture of lines and surfaces, shape of features such as curves and angles, use of colour for partially sighted people), what kind of audio description should accompany the tiles and how it should be activated. The team will research existing approaches being taken by other museums, arts organisations, companies and BPS groups, with whom the Museums already have strong links.

The R&D strand, to be led by Iain Emsley, Research Associate at the e-Research Centre, will determine how best to develop cheap and efficient methods of creating touch tiles that can provide the tactile sensations identified in strand one. It will also develop practical and replicable approaches to integrating audio delivery into the touch tiles.

Thirdly, the project team will select works of art from the Ashmolean's Western Art collection to prototype and user-test the technology. Learnings from this will be used to fine tune the user experience and gain a deeper understanding of the impact of this technology on the BPSP experience of visual art. At the end of the prototyping phase an installation of the touch tiles in the Ashmolean Museum will allow testing and evaluation with BPSP visitors in a real-world environment.

A pan-European team of researchers involving the University of Oxford has developed a new technique to provide cellular 'blueprints' that could help scientists interpret the results of X-ray fluorescence (XRF) mapping.

XRF imaging is used for a wide range of elemental analyses and has a number of medicine-based potential applications, including tracking and understanding diseases such as Alzheimer's, and the evaluation of heavy metal poisoning.

One barrier facing this technology has been the lack of cellular blueprints with which to compare the maps arising from XRF imaging. Now, researchers have been able to seal non-biological elements inside carbon nanotubes – tiny tubes 50 thousand times thinner than a human hair – to create 'nanobottles' that can be directed to individual cells to help create these blueprints.

The results of the study are published in the journal Nature Communications.

Dr Chris Serpell, a lecturer in Chemistry at the University of Kent who worked on the project while carrying out a research fellowship in Professor Ben Davis's group at Oxford, said: 'What's amazing about these findings is that the non-biological elements are toxic or gaseous, but they’re securely sealed within the nanobottles by just a single layer of carbon atoms. We're really pleased that this paper can showcase the biological potential of carbon nanotubes.'

Dr Serpell says that by using the contents of these nanobottles – such as barium, lead or gaseous krypton – as 'contrast agents', XRF imaging could become a much more widespread technique, providing insights into behaviours of proteins that use metals, and the role they have in health.

He added: 'Carbon nanotubes were once touted as a panacea to almost every technological problem, but in recent years people have become much more cynical about their utility. These results show that there are unique applications which are only possible using nanotubes – they are now moving towards realistic applications.

'Although it is at a very early stage in the pipeline, this technology can be expected to yield new insights into disease states and the effects of heavy metal poisoning, which can in turn lead to new healthcare technologies. A similar approach could also be used to deliver radioactive elements specifically to tumours for therapy, or to enhance other imaging modes such as MRI.'

Professor Davis, from Oxford's Department of Chemistry, said: 'This work was part of a training network across Europe known as RADDEL that was launched based on an earlier discovery that radioactive iodide could be packed into sealed tubes to be used in living animals.

'This new research has expanded on that finding, creating a spectacular system that encapsulates much more difficult elements and images these in cells using the rarely used technique of XRF. We have been able to use this method to see how the tubes find their way into different compartments in individual cells, controlled largely by how we chemically "decorate" those tubes.

'It's a striking example of something that would be tough to do by any other construct – to take a gas and "bottle" it before steering the bottle to one compartment in a cell so that you can use the gas for imaging.'

The study was a collaboration involving researchers from the universities of Oxford and Kent, Diamond Light Source, and Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Have you ever noticed that liquid stays inside a straw when it’s held horizontally? Or that the same thing doesn't happen when you turn a glass on its side?

A team of researchers including Professor Dirk Aarts from Oxford University's Department of Chemistry has been investigating this phenomenon – one that's 'surprisingly difficult' to explain from a scientific point of view.

Professor Aarts worked with colleagues Carlos Rascón from Universidad Carlos III de Madrid in Spain and Andrew Parry from Imperial College London for the study, which is published in the journal PNAS. Professor Aarts said: 'We considered the following seemingly simple question: why does the liquid spill out when I hold a glass – say, of beer – horizontally, but stays in a straw when I do the same thing?

'This question is actually surprisingly difficult, especially when considering non-circular cross-sections of the capillaries, or tubes.

'For a liquid trapped between two parallel walls, and for a liquid trapped in a circular capillary like a straw, the answer is one that we would intuitively expect: the liquid wants to flow out because of gravity, but is trapped due to the surface tension.'

The 'capillary action' described here is the ability of a liquid to flow in narrow spaces, often in opposition to external forces such as gravity. For example, if you zoom in on the surface of water in a glass, you’ll see that it curves upwards by a couple of millimetres at the wall. This curve is known as the meniscus.

Professor Aarts said: 'The competition between gravity and surface tension leads us to the capillary length, which sets the height to which a meniscus will climb at a wall. Indeed, if the separation between the two walls is less than roughly the capillary length, or if a circular capillary has a diameter less than roughly the capillary length, the liquids will stay put. If not, the liquids will flow out.

'However, if you change the cross-sectional shape of the capillary – for example, making it a triangle – the situation may change completely, and for certain geometries the liquid may spill out at any length scale, well below the capillary length.

'We figured out how to calculate this behaviour for general cross-sectional shapes, although the actual numerical calculations, carried out by Carlos Rascón, took almost seven years to complete. One of the reasons for this was that the spilling out may occur via different pathways, and the crossovers between those pathways were hard to understand.'

The researchers were able to solve the problem by reducing it down to an equivalent two-dimensional problem, which is numerically more accessible. The paper shows how 'emptying diagrams' can be created by calculating the energy of the problem in 2D. As soon as the energy became smaller than zero, no 3D solution for the meniscus exists, and the liquid empties.

Professor Aarts added: 'The surprising result here is that a capillary may empty even at lengths much smaller than the capillary length. This has implications for any technologies where liquids are used or are present on small scales, such as microfluidics, biomedical diagnostics, oil recovery, inkjet printing and so on.'

- ‹ previous

- 115 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators