Features

Oxford University Museums and experts from the Saïd Business School are teaming up for the third instalment of their highly successful Oxford Cultural Leaders programme, which will take place from 26 to 31 March 2017.

The programme has been developed as a response to the clear message from governments across the world that cultural organisations need to look beyond the state for their income, demonstrating their commercial acumen and ability to deliver successful new business models.

Oxford Cultural Leaders addresses the need for cultural organisations to reinvent themselves as businesses, albeit not-for-profit, with entrepreneurial ways of thinking and behaving, by developing a cadre of leaders who are able to skilfully and confidently tackle these challenges.

'Future leaders in the cultural sector will need to develop the confidence to think about their organisations as sustainable entities,' says Tracy Camilleri, Director of the Oxford Strategic Leadership Programme at the Saïd Business School. 'This will require new skills and approaches – some learned from different sectors and disciplines. The Oxford Cultural Leaders Programme in my view provides a powerful platform for the development of this shared future.'

'Having access to expertise from across the cultural and business sectors has enabled Oxford to develop a programme that is unique within the museum and cultural sectors internationally,' says Lucy Shaw, Director the Oxford Cultural Leaders programme. 'The first two programmes successfully brought together dynamic leaders in an environment which encourages experimentation and innovation.'

Anette Østerby, Head of Visual Arts at the Danish Arts Council, has previously attended the programme. She says: 'What surprised me most was the programme's ability to suspend the participants’ status issues and positioning and create a trusting, open, generous and sharing environment between us. It allowed us to work really well together, and this did generate some incredible moments of co-creation.'

The programme faculty comprises of cultural sector leaders and business school experts including the Directors of Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum and Ashmolean Museum, the Executive Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, and the Director General of the Imperial War Museum.

Participants will stay at Oxford’s Pembroke College. The deadline for applications is 5pm on 4 January 2017. More information about the programme and how to apply is available on the website.

In a guest blog, Kimberley Bryon-Dodd from the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, highlights the work being done to combat growing malarial drug resistance.

Global efforts to try and treat and eradicate malaria are being hampered by increasing resistance of the disease-causing Plasmodium parasite to anti-malarial drugs.

A new study led by the University of Oxford has identified genetic markers linked to resistance to the anti-malarial drug piperaquine. This new information can be used as a tool to identify areas where resistance is emerging and where current treatment strategies are likely to fail.

The international collaboration, including researchers jointly from the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, carried out a genome-wide association study on approximately 300 Plasmodium falciparum samples from Cambodia to study the genetic basis behind piperaquine resistance.

Piperaquine is used in combination with another anti-malarial drug, artemisinin, as a recommended frontline malaria treatment in many areas of the world. With parasites becoming increasingly resistant to artemisinin, increasing resistance to piperaquine as well could become a major public health problem.

Dr Roberto Amato, lead author of the study said: ‘Our findings provide a tool to monitor in a rapid and cost-effective way the spread of resistance, ultimately helping public health officials deploying the most effective therapies.’

By studying the genome of the parasites infecting patients who were not responding to treatment, the scientists identified two markers linked with piperaquine resistance. One way that anti-malarial drugs can work is by targeting the biological process that allows parasites to digest haemoglobin in the red blood cells; a family of proteins called plasmepsins plays a key role in this process. The scientists found that parasites with extra copies of the genes encoding two specific proteins of the plasmepsin family were more likely to be resistant to piperaquine. A second genetic marker linked with resistance was found to be a mutation on chromosome 13.

Professor Dominic Kwiatkowski, director of the Centre for Genomics and Global Health, and a lead author on the study, said: ‘These findings provide the tools needed to map how far this resistance has spread, looking for these molecular markers in parasites in Cambodia and neighbouring countries. This will allow national malaria control programmes to rapidly recommend alternative therapies where possible and where needed, enhancing treatment for patients, and helping towards the ultimate goal of eliminating malaria.’

The results of the study are published in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases.

In the latest Oxford Sparks podcast, Oxford statistician Dr Jennifer Rogers explores the numbers behind recent alarming headlines linking processed meat with bowel cancer.

As podcast host Emily Elias notes, it was a bad day for meat eaters when the news broke, with The Sun opting for the headline 'Banger out of order – sausages and bacon top cancer list'.

Dr Rogers, Director of Statistical Consultancy at Oxford and a member of the Department of Statistics, says: 'You wouldn't believe how many maths teachers have said to me that bacon is banned in their house because of this 18% increase in bowel cancer. People just aren’t eating it anymore. I get so many people say to me, "Do I actually have to be worried?"'

The worries stemmed from a report released by the World Health Organization. Last year, bacon made its way on to a list that also includes arsenic, asbestos, alcohol and tobacco because scientists found a 'statistically significant' increased risk of getting bowel cancer.

Dr Rogers says: 'All "statistical significance" does is tell us whether or not something is a risk. It doesn’t really tell us anything about what that risk is – how big it is or how it affects us. There were lots of headlines saying that because bacon is on the same list as smoking that bacon and smoking were now just as risky as each other in causing cancer. And that is not true.'

Mass-produced factory bacon is made by injecting salty water and chemicals, including nitrates, into pork belly before it's cured.

Dr Rogers adds: 'If we look at lung cancer and smoking, for every 400 people we would expect four people to get lung cancer anyway, even without smoking. If you look at people who smoke 25 or more cigarettes every day, that goes up to 96 in every 400 people.

'Now compare that to what we get for bacon. Bowel cancer affects just over 6% of the population. So for every 400 people, you'd expect about 24 people to get bowel cancer anyway. Eating 50g of bacon every day increases this risk by 18%, which means if you were to take 400 people all who ate bacon every day, you would now expect 28 of those to get bowel cancer – an increase of four people in every 400, compared with 92 in 400 for smoking.

'So even though they both may cause cancer, to say they are both as risky as each other is probably pushing it a little too far.'

We should also note, says Dr Rogers, that people who eat lots of processed meat are perhaps less likely to live healthy lifestyles in general, which may contribute to the increased risk of bowel cancer. That's one of the problems with drawing conclusions from observational studies, as opposed to strictly controlled clinical trials, she adds.

While the WHO report did cause bacon sales to suffer a short-term hit, things seem to have recovered since the more measured reality around the initially startling headlines came to light.

Dr Rogers, who has her bacon sandwiches with red sauce, no butter and toasted bread, concludes: 'I think that sometimes numbers and percentages can be hard to get our heads around and it's easier just to say, "I'm not going to eat bacon."

'I was recently asked to comment on something else that had been added to the "gives you cancer" list – drinking really hot drinks. This time round, the newspapers were contacting statisticians before they wrote their headlines and articles because they'd learned a lesson from the bacon story.

'It turned out that you needed to be drinking really extreme temperatures of mate tea in South America – not the temperatures that we have our hot drinks at.

'It would have been really easy for the newspapers to say that drinking hot drinks gives you cancer – and that would have caused an uproar.'

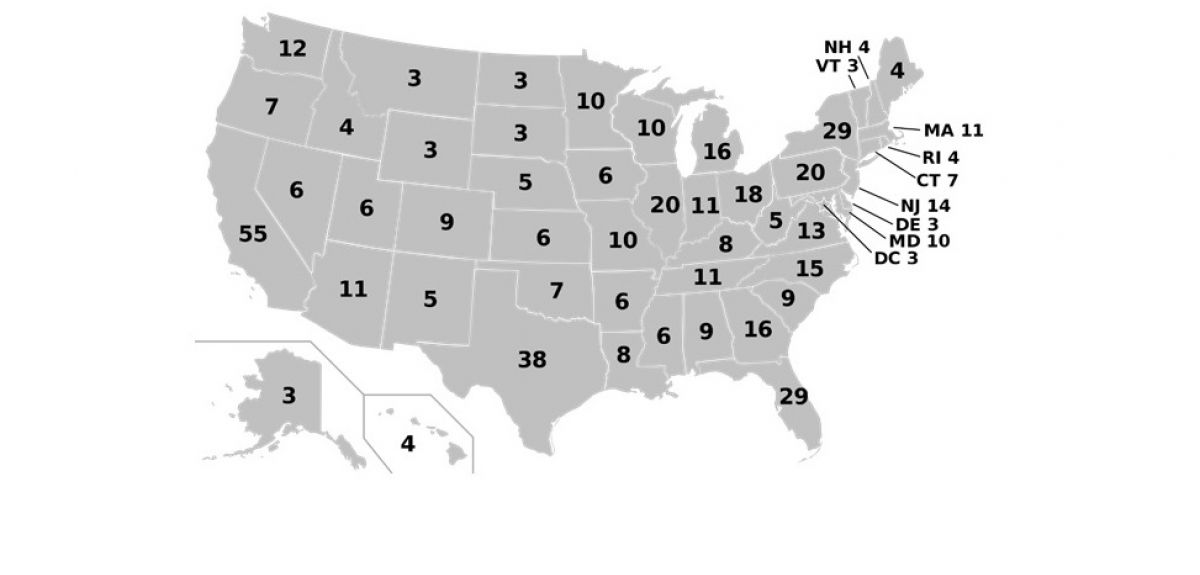

After one of the most bitterly-fought presidential election campaigns of all time, US voters will finally cast their votes on Tuesday (8 November).

The following day (Wednesday 9 November), experts at Oxford University's Rothermere American Institute will be reviewing the results.

The Institute will hold an 'open house' from 9am on the Wednesday morning, then at midday there will be a discussion of the election results involving some of Oxford's top US politics experts.

The RAI's experts have been commenting on the election to local, national and international media throughout the election. They have also produced important research on the likely role of overseas voters in the election. Their report found that winning a majority of overseas voters – often amounting to just a few thousand votes – could be enough for the candidates to snatch certain swing states.

From 12pm to 1.30pm, Nigel Bowles, Tom Packer, and Nina Yancy will place the election in historical perspective, analyse what the result tells us about today's American political landscape, and reflect on what the implications may be for the place of the United States in the wider world.

Everyone is welcome to attend - whether or not you are exhausted from staying up to watch the results come in!

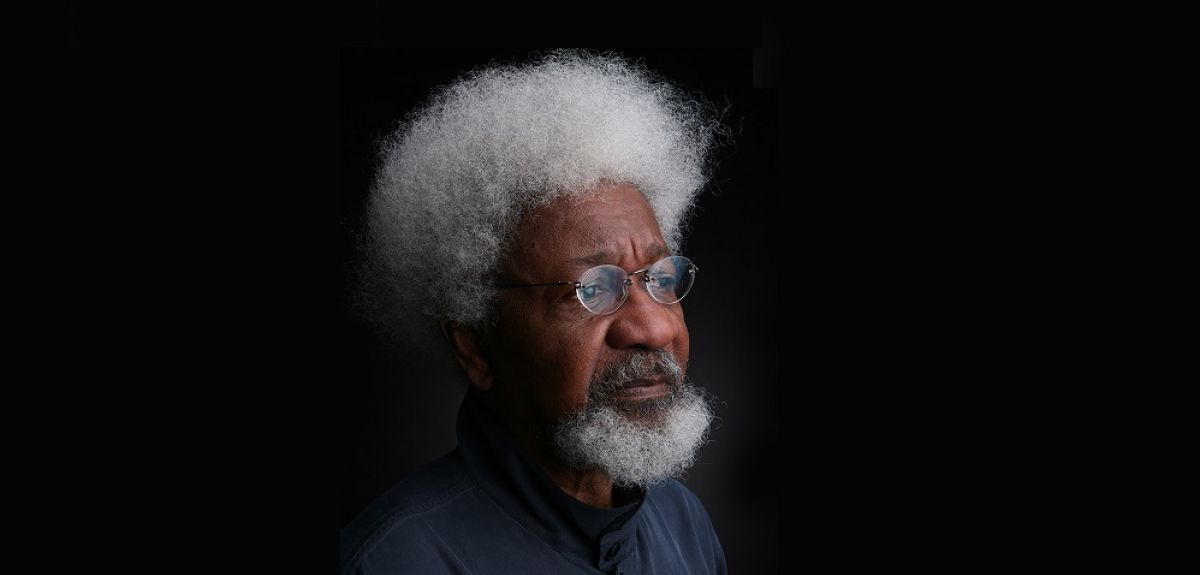

Brexit, Trump, Bob Dylan, pan-Africanism and Nigerian politics.

These were among the topics covered by the Nigerian Nobel Laureaute, poet, playwright and novelist Wole Soyinka when he spoke at Ertegun House recently.

The event was the inaugural Ertegun House seminar in the Humanities. The series brings into conversation members of the Ertegun House community and notable figures from the cultural, artistic, and academic worlds.

A video of the conversation is now available here.

Rhodri Lewis, Professor of English Literature and Director of Ertegun House, said the inaugural seminar was very successful and that Professor Soyinka offered “a tour de force of penetrating cultural commentary, delivered with measured but often playful outspokenness”.

The discussion was led by Professor Elleke Boehmer, who is Professor of World Literature in English at the University and the Director of The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Mayowa Ajibade, an Ertegun Scholar who is studying for a Master’s in World Literatures in English and was also born in Nigeria, attended the talk. He said: ‘I grew up attending theatre performances of Soyinka’s plays in Lagos, Nigeria.

I think Soyinka writes with a palpable reverence for what James Baldwin, the American writer, calls "the force of life," in its many manifestations. I am particularly fascinated by the peculiar way Soyinka writes about food and the experience of eating, for instance.

‘I definitely agree with Soyinka's assessment, in the interview with Professor Boehmer, that African Literature in its current state is "robust", "varied", and "liberated" from its former anxieties about ideology.

'I particularly liked Soyinka's complex understanding of the way language functions - i.e. as both a "creative agency in itself" and as an instrument - an agent - that is regulated by the particular experience it refers to.’

The next events in the series are as follows:

Quentin Skinner (Barber Beaumont Professor of the Humanities at Queen Mary, University of London; winner of Balzan Prize), 5.30pm, 24 February 2017.

Stig Abell (Editor, Times Literary Supplement), 5.30pm, 4 May 2017.

The seminar takes place once a term and is open to all members of the University.

Advanced registration is required in advance. Podcasts of each event will be made available on the website.

Ertegun House provides the Ertegun Scholarship Programme with a high-profile presence at Oxford. It is the base for the study and research of the Ertegun Scholars, and serves as a centre of innovation and activity across the humanistic disciplines.

It was founded in 2012 following a donation from Mrs Mica Ertegun.

For more information on the Ertegun Scholarship Programme, visit the website.

- ‹ previous

- 114 of 253

- next ›

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators