Features

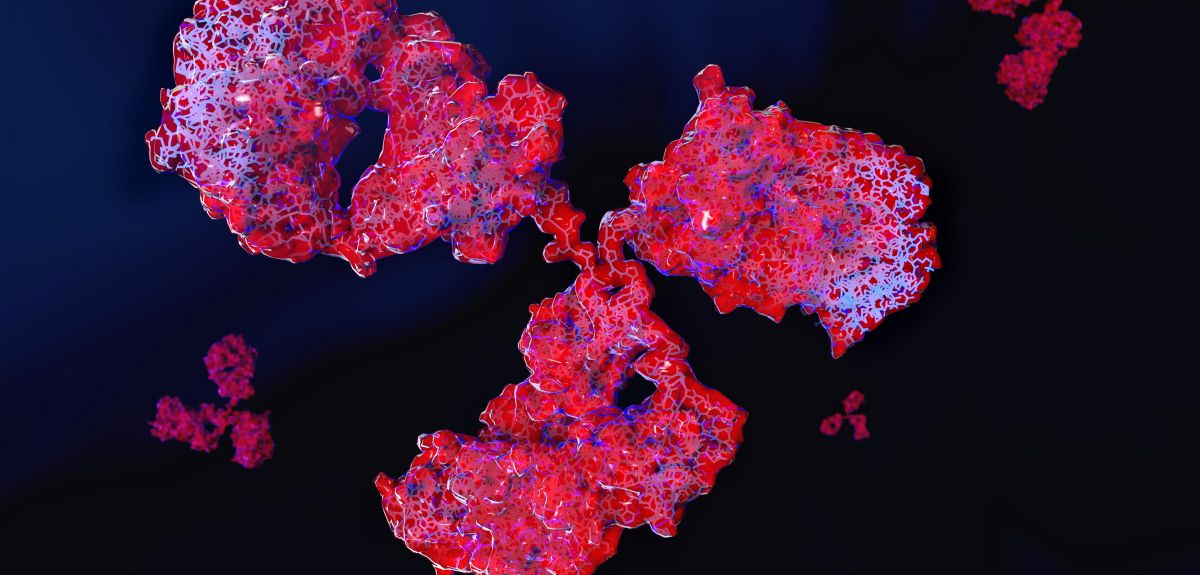

For the first time specific antibodies have been found to be associated with the onset of schizophrenia. A study published in The Lancet Psychiatry, reveals that certain kinds of antibodies appear in the blood of a significant percentage of people presenting with a first episode of psychosis. These antibodies, including those against the ‘NMDA receptor’, have previously been shown to cause encephalitis, a life threatening inflammation of the brain. This study now shows for the first time, that these same antibodies are also found in people with early presentations of schizophrenia.

Professor Belinda Lennox from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, who led the study, says: ‘We have shown that 8.8% of people with a first episode of psychosis have an antibody in their blood that may be responsible for their illness. The only way to detect these antibodies is through doing a blood test, as patients with antibodies do not have different symptoms from other people with psychosis.’

The discovery offers fresh hope in terms of new treatment possibilities for people experiencing psychosis. This is because the rapid identification and removal of the same antibodies associated with encephalitis leads to a dramatic improvement, and often complete a cure from the illness. Professor Lennox and her team have successfully treated a number of patients experiencing psychosis, who have these antibodies, using this pioneering form of immunotherapy.

‘It began with a devastating psychotic episode and subsequent issues with my memory, sleep, temperature and emotional control,’ says Sarah, a patient of Professor Lennox. ‘My mood was in total flux, swinging from hallucinations and insomnia to sleeping all day and getting severely depressed. It took over a year before the autoimmune side of my illness was picked up on through a fortunate research trial. Three years following my episode I have finally responded after two infusions of immune drugs. I am regaining nearly all of my previous function. It has been like a miracle cure. It is terrifying to imagine that without the correct treatment my symptoms might never have improved. Psychosis, caused by NMDA antibodies, could have dominated and even claimed my life.’

Professor Lennox adds: ‘The next important step for this study is to work out whether removing the antibodies will treat psychosis in the same established way as is now used for encephalitis. To do this the research team are starting a randomised controlled trial of immune treatment in people with psychosis and antibodies, starting in 2017.’

This study, funded by the Medical Research Council, recruited 228 people with psychosis from Early Intervention in Psychosis services from across England, including Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. People were tested within the first six weeks of treatment. The study also tested a comparison group of healthy controls. They found NMDAR antibodies as well as other antibodies, in patients with psychosis. They did not find any NMDAR antibodies in healthy control subjects. When the patients with antibodies were compared with those patients without antibodies there were no differences in their symptoms or illness course.

Antibodies are produced by the immune system to fight infection and protect the body. Sometimes, however, the antibodies cause more problems than they solve – in so-called auto-immune disorders, such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosis – which is a term for the symptoms seen in schizophrenia – is where a person may experience hallucinations, delusions and confused and disturbed thoughts.

The story of first-hand experience of NMDAR encephalitis was eloquently described by Susannah Cahalan, the New York Post journalist in her book ‘Brain on Fire’, which has since been made into a feature film released this year.

The full paper ‘Prevalence and clinical characteristics of serum neuronal cell surface antibodies in first episode psychosis’ can be read in The Lancet Psychiatry.

In a guest post for Science Blog, Dr Chris Newman, Dr Mike Noonan and Dr Christina Buesching from Oxford's Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) (directed by Professor David Macdonald) write about their latest research into the ecology of climate change – that is, how changing weather conditions affect the abundance and distribution of animal and plant species.

How many people cycle to work in Oxford? Census the number of people cycling in on a sunny summer day and you will surely get a higher estimate than if you count cyclists on a rainy winter day.

This type of sampling bias is extremely pertinent to climate change ecology, because population estimates are based on the number of individuals that are observed, trapped, photographed or otherwise sampled. Nevertheless, studies rarely account for imperfect detection and have tended to assume that population trends are purely a reflection of actual climatic effects, disregarding how weather alters animals' behavioural responses.

In a recent paper published in the journal Global Change Biology, we tested the extent to which prevailing weather might skew the numbers of badgers trapped in a well-studied population at Wytham Woods – Oxford University’s research woodland.

Following 1,179 individual badgers through 3,288 capture-recapture events over 19 years, we found that temperature and rainfall had a substantial effect on badger 'trappability'. Crucially, weather conditions did not act in isolation, but interacted with how fat badgers were. This curious discovery exposes an important and often underappreciated factor: motivation.

Returning to our cycling analogy, if your job and livelihood depend on your cycling to work, the chances are you will readily – though perhaps begrudgingly – cycle in rain, hail, or snow. If you can easily work from home, however, or take a vacation day, the weather will have little effect on your behaviour.

Badgers, as it turns out, are no different. Their behaviour is heavily influenced by motivation, and thus our ability to census them is heavily influenced by changes in their behaviour. Badgers, of course, live in underground burrows called setts and can only be 'caught' – observed or camera-trapped – when venturing above ground.

While all badgers were less inclined to surface in wet, miserable conditions, fatter badgers had the luxury to be more choosy about when to emerge, living off stored fat reserves until better conditions presented themselves. Thin and more desperate badgers on the other hand, got caught even when poor weather prevailed.

From an ecological perspective, if not accounted for, this skewed sub-sample would also give the impression that badgers are thinner with prevailing wet weather. In reality, quite the opposite is true: because badgers eat earthworms that surface in cool, wet conditions, they tend to be fatter following periods of wetness. This leads to a reinforcing loop, where fatter badgers are harder to catch. Consequently, when the population was generally in good condition, fewer badgers were caught, and vice versa.

More problematic still is that the difference of around 10% in trappability we recorded between best and worst weather scenarios is amplified further by capture-mark-recapture statistical models used to estimate actual population size from patchy individual trap histories. If worst-case-scenario weather is perpetuated over several consecutive seasonal trap-ups, it could cause up to a 55% population underestimate, whereas sustained best-case weather could lead to a 39% overestimate.

Now, there are direct practical implications to these findings. Badgers are culled in the UK in an attempt to alleviate the spread of bovine tuberculosis (bTB) in cattle. But failures by DEFRA to meet cull targets, and thus to achieve a worthwhile level of decrease in badger populations, have attracted criticism. In 2014, only 341 of the targeted 316-435 badgers were culled in Somerset, and only 174 of the targeted 615-1091 in Gloucestershire.

Extrapolating from our findings, it was immediately apparent that relatively cold, wet conditions during that autumn had done DEFRA's cull no favours. If warmer and drier conditions had occurred, the Somerset cull would likely have got close to its upper quota target – but in Gloucestershire, although trapping success would have been better, it would still have been fallen short of minimum quota targets.

Two crucial points emerge from our work. First, in terms of climate change logic, because there has been a steady trend for global warming over the last century, everything else developing over this period correlates with global warming – that is, correlation does not imply causality. This has been neatly satirised by Bobby Henderson's internet spoof, which shows a statistically significant relationship between increasing temperatures and the shrinking numbers of pirates since the 1800s. Studies on climate change must therefore focus on the precise mechanisms involved, avoiding spurious correlations.

Second, because an animal will initially attempt to respond to inclement weather by modifying its behaviour, population-level effects on reproduction and survival will only become apparent when conditions become too extreme for individuals to adapt to – where only long-term studies can elucidate genuine population trends from variation due to unanticipated correlations.

In short, the risks posed by climate change to species and ecosystems, as well as to human enterprises, are too serious for us to get things wrong. As the bTB example shows, management interventions or conservation strategies, implemented under unsuitable weather conditions, will fall short of targets. If the predictions made by scientists are based on faulty data, policies based on these data are destined to fail, adding to the malaise of misguided opinion surrounding global warming.

Artist Helen Marten, who studied at the Ruskin School of Art and Exeter College from 2005 to 2008, has won this year's Turner Prize.

In her last year at the Ruskin School, in 2008, she was interviewed in a video discussing her studies. That video can be seen here.

Helen spoke about the benefits of studying art in a close-knit group within a wider university. 'It usually works out that you have a few people [within the Ruskin] who become your sounding barriers or the people you talk to most about your work and their work,' she said.

'So you generally find that your critical space is within the school because they are the people who know most of the time exactly what you’re doing, what you’re thinking, what you’re talking about, things you’re looking at.

'But then because you have friends outside the school, there are people you will just chat to and there are lots of tangents which is good.'

Helen said that she benefited from working alongside art students at different stages of their degree.

'I think the vertical relationships are really nice because there’s a real framework,' she said. 'The guy in the year above you knows how to jigsaw something better than you so if you need to learn that, you’ll learn it, and it’s a building up of bits and pieces that eventually give you something a bit more full.

'There is no hierarchy or distinction between a first year and a third year, there’s a real network of friendships and of people’s knowledge that is good.'

She talked about what art students did outside of Oxford's eight-week terms. ‘Quite a few of us from our year all travelled around Germany and Venice this summer seeing various big shows,' she said.

'Maybe something that is symptomatic of really short terms is that there is quite a nice bleed over term times.

'Even though term is finished it’s not like the Ruskin is finished because a lot of people are doing stuff together anyway, like seeing shows in London or going away together.'

The interviewer in the video was Richard Wentworth, who was head of the Ruskin School at the time. His closing comments on Helen and her fellow students now seem prophetic.

'All three of you have worked really hard, you have been incredibly productive and a lot of artists would be put to shame by what you've generated in that time,' he said.

'I've never seen a year be critical like this.'

A new doctoral studentship at Oxford University has been set up in memory of Professor Stuart Hall.

Applications are now open for the DPhil studentship, which will run from 2017-2020 thanks to a collaboration between The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), Merton College and the Stuart Hall Foundation.

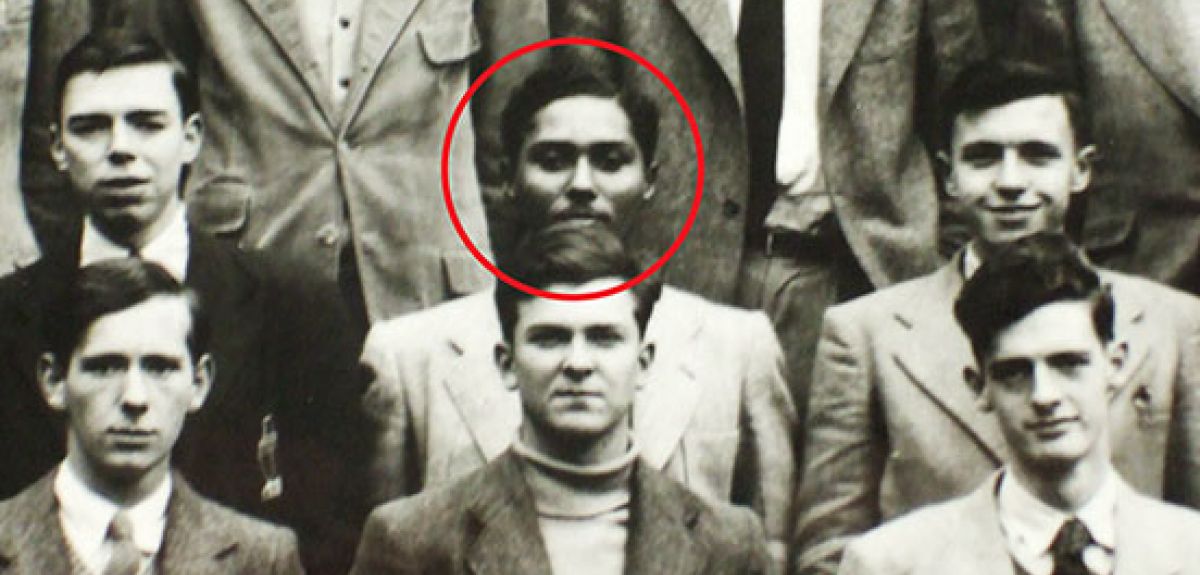

Professor Stuart Hall (1932-2014) was one of the founding figures of British cultural studies, best known for his work around cultural identity, race, and ethnicity, much of which serves as the basis for contemporary cultural studies today.

The successful applicant can come from any humanities discipline with particular research interests in Professor Hall’s areas of expertise.

They will also be part of TORCH’s two-year headline research theme for 2017-18, called Humanities & Identities, which will facilitate opportunities for research on areas that link to diversity and inclusivity.

Professor Hall championed racial and gender equality, and was a catalyst for a number of significant initiatives including journals the New Left Review and Soundings, the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, and the Open University.

He was born in Jamaica, and came to Oxford in 1951 to study English as an undergraduate at Merton on a Rhodes Scholarship. Over the course of his career he taught in London, at the University of Birmingham, and at the Open University.

Last month, TORCH and Pembroke College also helped to host the 40th anniversary Callaloo Conference, which is the annual conference of the Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters Callaloo.

Professor Elleke Boehmer, Director of TORCH, says: 'For over 55 years, from the time he came to Merton College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar from Jamaica, Stuart Hall was one of Britain's leading Black intellectuals, and a pioneer of what we now call cultural studies, who theorized not only questions of Blackness but also Britishness, not only what it was to be an immigrant in these islands, but also what it was to belong.

'The Black Arts journal Callaloo's 40th anniversary conference, which is being hosted by TORCH and Pembroke College this month, will explore Hall's legacy, and impact on debates about race and identity. What excellent timing it then is that Merton College and TORCH are at the same time announcing a new DPhil studentship in Stuart Hall's name.'

More information on the project is available here.

The idea of 'hygge' as cosy domestic bliss has become popular across the world, particular in the winter months. But in a guest post, Daniel M. Grimley, an expert in Scandinavian music at Oxford University, explains that the real meaning of 'hygge' is not quite as simple.

'The evenings lengthen and the air grows chill. Through a window can be glimpsed candles flickering upon an old wooden table, family and close friends gathered round an open fire, gentle conversation or contented quiet, and a feeling of homeliness and security. For a moment, at least, the world seems at peace.

As the winter gloom descends once more, and global events take a dark turn, it is hard to resist such cosy images of domestic well-being: that intimacy and comfort which Scandinavians call ‘hygge’. So pervasive does ‘hygge’ seem, it appears almost impossible to escape the associated allure of woollen jumpers, hot drinks, and artisan linen sheets.

‘Hygge’ has become a marketing tool promoted in glossy magazines and commercials, a designer brand that belongs to an imaginary Scandinavia of elegant furniture, crisp nights, and soft indoor lighting: a land of fairytale and nordic myth.

Far from being simply a global trend, however, ‘hygge’ is a historically contingent term that has baleful consequences for our contemporary predicament. Defining precisely what ‘hygge’ means, for non-Scandinavians, proves frustrating. Even its pronunciation remains a challenge. In Danish, it is spoken softly, and consists of two syllables: the final vowel is only lightly stressed, whereas the first is closer to a French ‘y’ than the Anglo-German ‘u’.

The word is a noun: the adjectival form is ‘hyggelig’. It shares the same etymology as the English ‘hug’, from the old Icelandic ‘hugga’, meaning to embrace or to soothe: it is intimately linked, in other words, with the body and with domestic space as a protective (and protected) realm.

In its more contemporary usage, ‘hygge’ emerges in nineteenth-century Danish literature as part of a more integrated sense of community and belonging (‘samfund’ or ‘fælleskab’), especially following the Prussian-Danish wars in 1848 and 1864. This shift of emphasis is consonant with the reformist philosophy of thinkers and theologians such as Nikolai Grundtvig, and also with Scandinavia’s increasing awareness of its geopolitical position: a largely agrarian society that had come relatively late to industrialization, and which found itself on the edge of more belligerent imperializing powers.

In our own post-industrial condition, such inward domesticity has begun to appear especially attractive, and assumed an increasingly nostalgic character. Its legacy is still felt in Nordic architecture and design, which largely eschews the monumental in favour of a more human sense of size and shape.

It has similarly helped to sustain the much-admired Scandinavian welfare model, with its principles of openness, equality, and humanitarianism. Through this doctrine of care and support that the idea of ‘hygge’ so powerfully embodies, Scandinavia has been a global beacon, a focus for the homely celebration of fellowship and shared responsibility upon which the world increasingly depends.

The sense of community upon which ‘hygge’ has relied, however, has not always seemed so passively benign. As Paul Binding’s brilliant recent biography has shown, many of H. C. Andersen’s short stories, paradigmatically ‘The Little Match Girl’ (‘Den lille pige med svovlstikkerne’), sharply juxtapose evocations of cosiness and intimacy alongside astonishing emotional cruelty and psychological pain.

Generations of artists and writers, including Henrik Ibsen, Edvard Munch, Selma Lagerlöf, and August Strindberg, railed against the suffocating effect of the social conformism and complacency that dominated nineteenth-century nordic society, and sought refuge or relief in biting satire and opaque symbolism.

There is little sense of ‘hygge’, for example, in the chilly paintings of Vilhelm Hammershøi or the ‘blue’ interiors of Harriet Backer, or in the fiery social critique of authors such as Martin Anders Nexø. The great Danish composer Carl Nielsen, whose songs are still sung daily by children across Denmark, once described himself as ‘a bone of contention, because I wanted to protest against all this soft Danish smoothing-over, I wanted stronger rhythms, more advanced harmony’. A less ‘hyggelige’ artistic manifesto is difficult to conceive.

Here, then, lies a more complex and critical engagement with ‘hygge’: in the recognition that its warming embrace, and the idealized domestic cosiness with which it is intertwined, can swiftly become stifling and claustrophobic. The enclosure that is so central to the feeling of being hyggelig can unexpectedly have the opposite effect, shutting out the world and excluding people more rapidly than it gathers them together.

This is a more telling indictment of contemporary Scandinavia, as it struggles to address global crises that are beyond its control. The impression of protected domestic space, and of turning inwards, can lead to hardened physical boundaries and political borders, especially if that space appears compromised or threatened.

Within this notion of ‘hygge’, as it has been popularized and disseminated, must also lie the waves of xenophobia and violence, and the rise of the far-right, that have increasingly fractured the Scandinavian political landscape, and which have stretched nordic notions of tolerance and open-mindedness almost to breaking point.

Perhaps, then, a new kind of ‘hygge’ is required, one less tied to complacent notions of lifestyle and material comfort. Its proper meaning and value lie not in elegant furniture, soft candlelight, and high-end designer knitwear, but in the need to extend human warmth and responsibility.

Those friends and family who should be drawn close are not those to whom we are most closely related, but rather those from whom we feel most different and remote. This is a different kind of domesticity, and a different sense of homeliness. As winter deepens, and the darkness grows once more, reaching out becomes increasingly imperative.

It is only then that such images of comfort and security can genuinely regain their glow, and that Scandinavia can begin to feel ‘hyggelig’ once more.'

- ‹ previous

- 109 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria