Features

Today marks 70 years since the first of the Nuremberg trials began.

Dr Jan Lemnitzer, historian at Pembroke College, Oxford University, researches how modern international law was created in the 19th century, how it came to be applied across the globe, and what that meant for international politics.

Here, he writes about the legacy of the Nuremberg trials:

On November 20 1945 the first of the Nuremberg trials began in the main court building of the Bavarian town of Nuremberg with the indictment of 22 of the most senior Nazis that had been captured alive.

Here in the dock were the architects and enforcers of the Holocaust and the Nazi regime’s countless other crimes – among them were Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe and the Nazi rearmament effort; Hans Frank, who had treated Poland like his personal fiefdom and acquired the nickname “the Butcher of Kracow”; Hans Sauckel, who had organised the Nazi slave labour programme.

The trials are widely celebrated as a triumph of law over evil and marking an important turning point in legal history because dealing with the crimes of the Nazis paved the way for justice in the international community in general and the creation of the International Criminal Court in particular. It is this version of the story which has inspired the city of Nuremberg, which also hosted the infamous Nazi party rallies in the 1930s, to launch a new academy to promote the “Nuremberg principles”.

But while Nuremberg is celebrated today, the legal reality is not as clear-cut. As leading international criminal lawyer William Schabas remembers, “when I studied law, in the early 1980s, the Nuremberg Trial was more a curiosity than a model”.

The trials were also plagued by allegations of being little more than victor’s justice. These were made not only by Germans but also by American and British lawyers who felt it was a legal travesty. The judges and prosecutors were not neutral, but came from the four victorious powers – which led to such oddities as a Soviet prosecutor citing the Hitler-Stalin pact as evidence of German aggression against Poland, or a Soviet judge with ample experience of running Stalinist show trials trying to persuade his colleagues that the massacre against Polish officers in Katyn (who had been shot by the Soviets) should be added to the tally of German war crimes.

But the hypocrisy was not exclusive to the Soviet side: the London Charter of August 8 1945 which established the tribunal explicitly limited its remit to war crimes committed by the Axis powers. The tribunal also applied the so-called tu quoque principle which holds that any illegal act was justified if it had also been committed by the enemy (the Latin phrase means “you, too”).

Leading Nazis, Hermann Göring, Karl Dönitz, and Rudolf Hess at Nuremberg. United States Army Signal Corps photographer via Harvard Law Library

No Nazi was charged with terror bombardment since the use of strategic bombardment against civilians had been a pillar of the British and US war efforts. And when US admiral Chester W. Nimitz testified that the US Navy had conducted a campaign of unrestrained submarine warfare against the Japanese from the day after Pearl Harbor, the relevant charges against Admiral Karl Doenitz were quietly dropped.

Wisely, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia dismissed tu quoque as fundamentally flawed.

So why celebrate this trial?

One reason to celebrate Nuremberg is the simple fact that it happened at all. Until just before the end of the war, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin favoured summary executions of thousands of leading Nazis as the appropriate form of retribution. An outcry among the US public once these plans were leaked was a major factor in laying the road to Nuremberg.

Instead of mass shootings, an old idea from the First World War was revived. The Versailles treaty had compelled Germany to hand over Kaiser Wilhelm II and hundreds of senior officers to an international tribunal to be tried for war crimes. But the Kaiser fled to the Netherlands and the German government refused to hand over any officers or politicians. This time, however, Germany was completely occupied and was unable to resist, so the trials went ahead.

Flawed or not, the Nuremberg tribunal could not have met a more deserving collection of defendants – and it gave them a largely fair trial. Next to 12 death sentences and seven lengthy prison terms, the judgements included three acquittals – one of them for Hans Fritzsche, who had been the regime’s public voice on radio but was not personally involved in planning war crimes.

Crucially, the Nuremberg trials established an irrefutable and detailed record of the Nazi regime’s crimes such as the holocaust at precisely the time when many Germans were eager to forget or claim complete ignorance.

The legacy: important but inconvenient

Today, the most relevant legacy are the “Nuremberg principles”. Confirmed in a UN General Assembly resolution in 1948, they firmly established that individuals can be punished for crimes under international law. Perpetrators could no longer hide behind domestic legislation or the argument that they were merely carrying out orders.

The Nuremberg trials also influenced the Genocide Convention, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva conventions on the laws of war, all signed shortly after the war.

The strongest impact should have been on the development of international criminal law, but this was largely frozen out by the Cold War. With the re-emergence of international tribunals investigating war crimes and genocide in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the 1990s, the legacy of Nuremberg proved a powerful argument for establishing the International Criminal Court in 1998.

The Rome Statute includes many principles developed in 1945, so the United States as the main proponent of the Nuremberg trials could take great pride in its impact, were it not for the fact that successive US administrations have fought tooth and nail against the ICC’s insistence that international criminal law might one day be applied against US citizens. So, 70 years later, Nuremberg’s legacy continues to be inconvenient.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.

A new computational model helps to find innovative ways to tackle the dangerous problem of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Doctoral student Dan Nichol explains his research.

Antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria are currently causing an annual worldwide death toll totalling hundreds of thousands of lives. A recent report from the Review of Antimicrobial Resistance, commissioned by the government, suggests that this number could reach 10 million by the year 2050. This rapid increase in the rate of antibiotic resistance has been coupled with a drastic slowdown in the discovery of novel antibiotic compounds. It is becoming ever clearer that this crisis cannot be solved simply by discovering novel antibiotics; instead we must find new uses for existing drugs in treating highly-resistant disease.

This crisis cannot be solved simply by discovering novel antibiotics; instead we must find new uses for existing drugs in treating highly-resistant disease.

Traditional medical wisdom is that to effectively treat infections we should prescribe the most effective drugs, at the highest tolerable dose, for as long as is needed to clear the infection. However a new paradigm, known as adaptive therapy, which has emerged from mathematical modelling of the treatment of bacterial infections, viruses and cancer suggests that this strategy may be driving resistance.

By considering disease from the Darwinian perspective, where treatment imposes selective pressure and drives the evolution of resistance, mathematical modelling (coupled with biological experiments and clinical observation) suggests that the optimal treatment strategy may be to prescribe multiple drugs, in sequence or in combination, to pre-empt or exploit evolution.

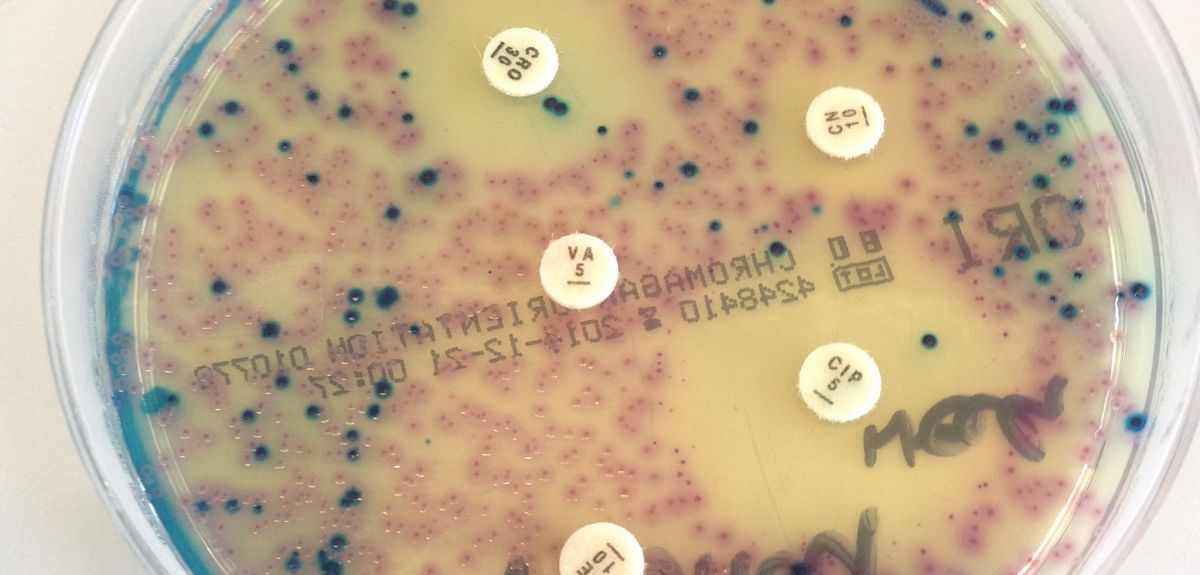

Using a simple computational model which encodes the population dynamics of an evolving bacterial population as a Markov chain, Daniel Nichol and Jacob Scott have built a tool capable of predicting sequential adaptive therapies for E. coli which reduce, and in many cases entirely prevent, the risk of highly resistant disease emerging.

To design these adaptive therapies it is first necessary to predict how a population of bacteria will evolve. Recently published empirical measures of the fitness landscapes of E. coli under fifteen different antibiotics have made these predictions possible. A fitness landscape is a mapping which assigns to each possible bacterial genotype an associated level of resistance, or fitness, to a given drug. The landscape metaphor, first introduced by Sewell Wright in the 1930s, is a visualisation of this mapping as a surface on which an evolving population ‘climbs’ uphill.

The order in which drugs are given will have a significant impact on the final state after evolution.

By considering the relevant bacterial genotypes as the vertices of a weighted directed graph, where the edge weights encode the probability of a change in the population genotype, this ‘uphill climb’ in the fitness landscape can be reduced to a biased random walk on a graph. By encoding this random walk formally as a Markov chain, the complex process of evolution within a population of bacteria exposed to an antibiotic is reduced to a single matrix multiplication. The immediate consequence of this model is that, as matrix multiplication is non-commutative, the order in which drugs are given will have a significant impact on the final state after evolution. This observation leads to a natural question: are some orderings better than others?

In their work, published in PLOS Computational Biology, Daniel and Jacob show that the answer is ‘yes’. Using the recently published landscapes for E. coli, the research demonstrates that it is possible to prime the disease population using sequences of one to three antibiotics such that resistance to a final antibiotic cannot emerge. This finding suggests a new treatment strategy in fighting antibiotic disease: adaptive therapies which use sequences of drugs to steer, in an evolutionary sense, a disease population to a configuration from which it is both readily treatable but also from which resistance cannot emerge.

As well as demonstrating the possibility of adaptive, sequential therapy for treating highly-resistant bacterial infections, Daniel and Jacob also provide a cautionary warning regarding current clinical practice. When antibiotics are prescribed in sequence, as is often the case in treatment of H pylori, Hepatitis B or the transition from broad to narrow spectrum antibiotics, no guidelines presently exist to specify the order in which drugs should be given. Instead this decision is left to the clinician’s personal preference

Over 70% of drug sequences increase the likelihood of resistance emerging to the final drug when compared to giving that drug alone.

By checking all possible sequences of two, three or four antibiotics for which empirical landscapes are known, the research reveals that the majority, over 70%, of drug sequences increase the likelihood of resistance emerging to the final drug (when compared to giving that drug alone).

In particular, giving Piperacillin+Tazobactam, an antibiotic often used after others fail, as the final drug in a sequence of two or three antibiotics increases the likelihood of resistance arising in over 90% of cases. By giving drugs in arbitrary orders we may be inadvertently encouraging the emergence of antibiotic resistance just as giving drugs with incorrect doses can do so.

To move their theoretical findings towards the clinic, Daniel and Jacob have partnered with microbiologists at the Louis Stokes Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital in Cleveland to perform empirical tests of evolutionary steering. They are also working with Dr Alexander Anderson and Dr Robert Gatenby at the Moffitt Cancer Center, to adapt their model to predicting the effectiveness of cancer therapies.

A major impediment to designing adaptive therapies using their method is that measuring fitness landscapes is a complex problem where the number of strains that need to be synthesised grows exponentially with the number of mutations of interest. Despite this difficulty, empirical fitness landscape research, aided by machine learning techniques which help to reduce the number of strains that need to be synthesised, has grown rapidly in recent years. As this trend continues the potential for therapies exploiting evolutionary steering, and with it the role of computational models in designing treatment, will continue to grow - hopefully enabling better treatment for a variety of deadly diseases in the future.

This Sunday (22 November) the Ashmolean will host a free, fun-filled day of events and activities in which visitors will explore what it was like to be alive in Roman times, discover how the Romans remembered their dead and see newly installed displays in the museum's Roman Gallery.

Remembering The Romans features a programme of immersive performances, interactive workshops and lively talks for all ages, including Roman storytelling; ancient object handling; costumed performances; readings of ancient inscriptions; expert tours and talks; and drop-in Roman craft sessions.

The Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project , which involves academics from the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents in Oxford's Faculty of Classics, the Ashmolean Museum Warwick University, will also share their recent findings based on research, using the Ashmolean's remarkable Roman permanent collection to introduce visitors to their latest studies into Roman life, death and commemoration.

Other events include 'living history' specialist Tanya Bentham looking at the different clothes worn during the Roman Empire in a Roman Fashion Show and drop-in craft activities where visitors can carve their own inscriptions, test their code-cracking skills on real Latin inscriptions and handle Roman artefacts.

Professor Alison Cooley, Head of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick, and Helen Ackers of Oxford University's School of Archaeology, will be giving an expert tours of the Roman collections, looking at the lives of those depicted in Roman tombstones.

The event will run from 11am to 4pm.

The Ashmolean Latin Inscriptions Project (AshLI) is a three-year project to catalogue and share Roman stories from the Ashmolean Museum.

For more information on AshLI, follow them on Twitter and Facebook.

The World Health Organisation has declared that this week is World Antibiotic Awareness Week. Yet, resistance to antibiotics is only part of the wider issue of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Leading medical journal The Lancet has launched a series examining whether the global fight against AMR is under threat, with contributions from various researchers at Oxford University. Anne Whitehouse, from WWARN – the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network – explains more.

Are we doing enough to tackle the broader issue of resistance to a range of antimicrobial medicines that are used to kill and prevent the spread of bacteria, fungi and parasites?

Anne Whitehouse, WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network

It’s not so long ago that people with cold and flu symptoms were commonly found asking their GPs for antibiotics, despite the fact that antibiotics fight bacteria and are no use for colds and flu which are caused by viruses. In fact, antibiotics may do more harm than good and misuse results in resistance – when bacteria change and antibiotics stop working – meaning that these valuable medicines are no longer available to us when we really need them.

Huge strides have been made in informing the public about the consequences of taking antibiotics unnecessarily, but how much do we really know about the drivers of antibiotic resistance? Why is resistance so important, and are we doing enough to tackle the broader issue of resistance to a range of antimicrobial medicines that are used to kill and prevent the spread of bacteria, fungi and parasites?

A major new series, published in The Lancet today suggests that the global fight against antimicrobial resistance could be under threat unless we improve the evidence base for policies to control resistance and address the related areas of human and animal health and ecosystems.

Oxford authors' contributions in the Lancet anti-microbial resistance series

Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance

International cooperation to improve access to and sustain effectiveness of antimicrobials

Prof Philippe Guérin, director of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), based in the Centre for Tropical Medicine & Global Health at the University of Oxford, is co-author of a paper which investigates the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. He says: ‘The emergence of antimicrobial resistance is a natural evolutionary response to antimicrobial exposure, which requires further investigation and a coordinated approach. There are many complex and interlinking factors that are driving the prevalence of antimicrobial resistant organisms that are not yet fully understood.

‘It is clear that we need to take urgent action to combat the threat to human health. In the case of malaria, the significant steps that have been taken to reduce the burden of the disease are threatened by resistance to existing antimalarial medicines. Artemisinin derivatives, the cornerstone of malaria treatment, are now under threat as resistance to this family of drugs has emerged and spread across Southeast Asia in less than a decade. If drug resistance spreads from Asia to the African sub-continent, or emerges in Africa independently as we’ve seen several times before, millions of lives will be at risk.’

In the case of malaria, the significant steps that have been taken to reduce the burden of the disease are threatened by resistance to existing antimalarial medicines.

Prof Philippe Guérin, director of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network

The authors also suggest that current global efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance are too modest, and need to be coordinated by a new UN-level coordinating body. There should be renewed focus on understanding which policies will work, and an international treaty to enforce their adoption.There are no new antimalarials that are ready for distribution, and so prolonging the efficacy of antimalarial medicines is critical to reducing the number of people dying from the disease. Similarly, no major new types of antibiotics have been developed over the last 30 years, and so the authors suggest that the current incentives for pharmaceutical companies to develop new antimicrobials should be radically overhauled.

The World Health Organization (WHO) launched its first report on antimicrobial resistance last year and is drawing attention to the problem through initiatives such as World Antibiotic Awareness Week, taking place from 16-22 November. According to the WHO, antibiotic resistance is a serious worldwide threat to public health that is no longer a prediction for the future; it’s happening right now, across the world, and is compromising our ability to treat infectious diseases and undermining many advances in health and medicine.

The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, chaired by Jim O’Neill, also stressed the urgency of the problem, predicting 10 million deaths attributable to antimicrobial resistance every year by 2050, if appropriate action isn’t taken.

Of course, no-one is suggesting that antimicrobial medicines should be denied to those who need them. In fact, access to antimicrobial drugs remains a major issue, with more people dying every year from a lack of access to antimicrobials than those who die from infection by resistant organisms.

So, whilst we should be focusing on reducing over-prescription of antimicrobial medicines, we also need to further our understanding of resistance, conserve existing antimicrobials, support the development of new ones, and make sure that antimicrobial drugs are distributed to the people who really need them.

Bipolar disorder – formerly known as manic depression – is a chronic, recurrent mental illness characterised by extreme swings in mood. The condition is thought to affect at least one in every 100 adults worldwide and has the highest rate of suicide among psychiatric disorders.

But despite its prevalence and severity, little is known about the processes underlying the disorder, while treatments remain limited. Researchers at Oxford University have set out to address this by using mathematical modelling to better understand the 'mood dynamics' of people with bipolar disorder.

In a new paper published in Journal of the Royal Society Interface, academics investigate how the subjective experience of mood can be understood using oscillators that 'map' the fluctuations in mood reported by participants via the QIDS (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology) questionnaire system.

Michael Bonsall, Professor of Mathematical Biology in the Department of Zoology at Oxford, says: 'Bipolar disorder affects a huge number of people across the globe, so it's really important that we find new ways to understand it from both scientific and clinical points of view.

'For the last four or five years, we've been working on what we call "mood maths" – using mathematical modelling to tell us more about the variation in mood experienced by people with bipolar disorder. Collecting mood scores over time allows us to ask how important previous mood state is on current mood – how is mood dependent on recent events?

'And although episodes of depression or mania in people with bipolar disorder can be very infrequent, the inter-episode "average" mood can go up and down a lot.

'We want to be able to build mathematical structures that will allow us to drill down from the subjective idea of mood to how individual neurones in the brain are interacting.'

Using the oscillators in tandem with data reported by 25 participants with bipolar disorder, the researchers were able to show, in mathematical terms, what drives these fluctuations in mood.

Professor Bonsall says: 'In the future, we may be able to use maths in conjunction with self-reported data such as the QIDS score to help ascertain the efficacy of particular treatments for bipolar disorder. Eventually, that may even involve working out what is best for individual patients.

'That makes a study of this type really powerful.'

Professor John Geddes, Head of the Department of Psychiatry and one of the paper's authors, says: 'The application of mathematical approaches to mood data is very exciting. They provide insight into the nature of the mood instability that occurs in bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses and will help us understand the mechanism of the illness and develop better treatments. These analytic approaches have been made possible by advances in our ability to capture high-resolution data from patients remotely, the engagement of patients and our colleagues in other academic disciplines, and the support of our funders.'

The research was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

- ‹ previous

- 139 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria