Features

New research published in Nature Ecology & Evolution from the Department of Zoology at Oxford University aims to show how big data can be used as an essential tool in the quest to monitor the planet’s biodiversity.

A research team from 30 institutions across the world, involving Oxford University’s Associate Professor in Ecology, Rob Salguero-Gómez, has developed a framework with practical guidelines for building global, integrated and reusable Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBV) data products.

They identified a ‘void of knowledge due to a historical lack of open-access data and a conceptual framework for their integration and utilisation'. In response the team of ecologists came together with the common goal of examining whether it is possible to quantify, compile, and provide data on temporal changes in species traits to inform national and international policy goals.

These goals, such as the Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDG) of the United Nations, have become fundamental in shaping global economic investments and human actions to preserve and protect nature and its ecoservices.

Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) have been proposed as ideal measurable traits for detecting changes in biodiversity. Yet, the researchers say, little progress has been made to empirically estimate how EBVs in fact change through time at the regional and global scales.

To overcome this, Rob Salguero-Gómez and his international collaborators have developed a framework with practical guidelines for building global, integrated and reusable EBV data products of species traits. This framework will greatly aid in the monitoring of species trait changes in response to global change and human pressures, with the aim to use species trait information in national and international policy assessments.

Salguero-Gómez says: 'We have for the first time synthesised how species trait information can be collected (specimen collections, in-situ monitoring, and remote sensing), standardised (data and metadata standards), and integrated (machine-readable trait data, reproducible workflows, semantic tools and open access licenses).'

This latest review provides a perspective on how species traits can contribute to assessing progress towards biodiversity conservation and sustainable development goals. The researchers believe that big data is one of the keys to address the global and societal problems from security food, to preventing ecoservice loss, or effects of climate change.

They say that the operationalization of this idea will require substantial financial and in-kind investments from universities, research infrastructures, governments, space agencies and other funding bodies. ‘Without the support of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, NERC, Oxford, and the open-access mentality of hundreds of population ecologists, our work with COMPADRE & COMADRE would not have been possible,’ says Salguero-Gómez.

The integration of trait data to address global questions in ecology, evolution, and conservation biology is one of the main themes in Salguero-Gómez’ research group, the SalGo Lab.

This work was funded primarily by the Horizon 2020 project GLOBIS-B of the European Commission.

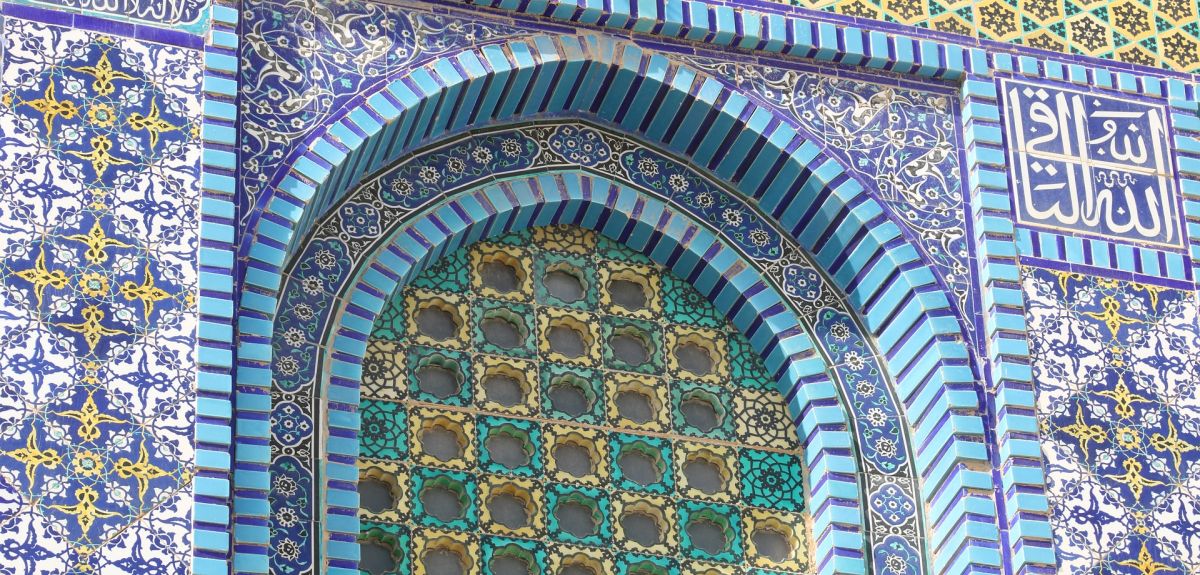

How did the ancient Middle East transform from a majority-Christian world to the majority-Muslim world we know today, and what role did violence play in this process? These questions lie at the heart of Christian Martyrs under Islam: Religious Violence and the Making of the Muslim World (Princeton University Press), a new book by associate professor of Islamic history Christian C. Sahner. In a guest post for Arts Blog, Professor Sahner, from Oxford's Faculty of Oriental Studies, explores his findings.

Although Arab armies quickly established an Islamic empire during the seventh and eighth centuries, it took far longer for an Islamic society to emerge within its frontiers. Indeed, despite widespread images of “conversion by the sword” in popular culture, the process of Islamisation in the early period was slow, complex, and often non-violent. Forced conversion was fairly uncommon, and religious change was driven far more by factors such as intermarriage, economic self-interest, and political allegiance. Non-Muslims were generally entitled to continue practising their faiths, provided they abided by the laws of their rulers and paid special taxes. Muslim elites sometimes even discouraged conversion, for when non-Muslims embraced Islam, they no longer had to provide these taxes to the state, and thus the state’s fiscal base threatened to contract. Compounding this was a belief among some that Islam was a special dispensation only for the Arab people. Thus, when non-Arabs converted, they were sometimes treated as second-class citizens, despised as little better than Christians, Jews, or other “infidels”.

This combination of factors meant that the Middle East became predominantly Muslim far later than an older generation of scholars once assumed. Although we lack reliable demographic data from the pre-modern period with which we could make precise estimates (such as censuses or tax registers), historians surmise that Syria-Palestine crossed the threshold of a Muslim demographic majority in the 12th century, while Egypt may have passed this benchmark even later, possibly in the 14th. What we mean by the “Islamic world” thus takes on new meaning: Muslims were the undisputed rulers of the Middle East from the seventh century onward, but they presided over a mixed society in which they were often dramatically outnumbered by non-Muslims.

It is against this backdrop that the phenomenon of Christian martyrdom took place. We know about these martyrs thanks to a large but understudied corpus of hagiographical texts written in a variety of medieval languages, including Greek, Arabic, Latin, Syriac, Armenian, and Georgian. Set in places as varied as Córdoba, the Nile Delta, Jerusalem, and the South Caucasus, they tell the lives of Christians who ran afoul of the Muslim authorities, were executed, and were later revered as saints. The martyrs were participants in this broader culture of conversion, but as their deaths make clear, they were also dissenters from this culture, individuals who protested Islamisation and attempted to reverse the tide of religious change.

The first and largest group consisted of Christians who converted to Islam but reneged and returned to Christianity. Because apostasy came to be considered a capital offence under Islamic law, they faced execution if found guilty. The second group was made up of Muslim converts to Christianity who had no prior experience of their new religion. The third consisted of Christians who were executed for blasphemy; that is, publicly reviling the Prophet Muhammad, usually before a high-ranking Muslim official. The martyrs were small in number – not more than around 270 discrete individuals between Spain and Iraq – a testament to the relative absence of systematic persecution at the time.

As a collection of texts, the lives of the martyrs represent one of the richest bodies of evidence for understanding conversion in the early medieval Middle East. Yet these sources must be treated with great caution. Saints’ lives are a notoriously formulaic genre, filled with reports of miracles, literary motifs, and theological polemics which can make it difficult to know what “really happened”. Reading the sources alongside contemporary Islamic texts, the book argues that many biographies have a strong basis in reality. At the same time, they were shaped by the literary, social and spiritual priorities of their authors, who were determined to create models of resistance for their flocks, who were increasingly tempted by the faith and culture of the conquerors.

Christian Martyrs under Islam describes a lost world in which Muslims and Christians rubbed shoulders in the most intimate of settings, from workshops and markets to city blocks and even marital beds. Not surprisingly, these interactions gave rise to overlapping practices, including behaviours that blurred the line between the Islam and Christianity. To ensure that conversion and assimilation went exclusively in the direction of Islam, Muslim officials executed the most flagrant boundary-crossers, and Christians, in turn, revered some of these people as saints.

Stephen Pates, a researcher from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, has uncovered secrets from the ancient oceans.

With Dr Rudy Lerosey-Aubril from New England University (Australia), he meticulously re-examined fossil material collected over 25 years ago from the mountains of Utah, USA. The research, published in a new study in Nature Communications, reveals further evidence of the great complexity of the oldest animal ecosystems.

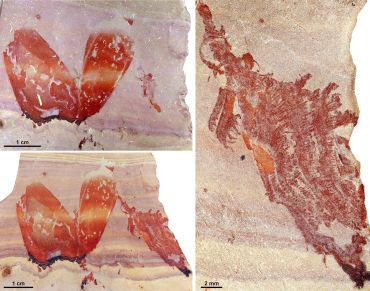

Twenty hours of work with a needle on the specimen while submerged underwater exposed numerous, delicate microscopic hair-like structures known as setae. This revelation of a frontal appendage with fine filtering setae has allowed researchers to confidently identify it as a radiodont – an extinct group of stem arthropods and distant relatives of modern crabs, insects and spiders.

Before and after view of Pahvantia

Before and after view of Pahvantia ‘Our new study describes Pahvantia hastasta, a long-extinct relative of modern arthropods, which fed on microscopic organisms near the ocean’s surface’ says Stephen Pates. ’We discovered that it used a fine mesh to capture much smaller plankton than any other known swimming animal of comparable size from the Cambrian period. This shows that large free-swimming animals helped to kick-start the diversification of life on the sea floor over half a billion years ago.’

Causes of the Cambrian Explosion - the rapid appearance in the fossil record of a diverse animal fauna around 540-500 million years ago - remain hotly debated. Although it probably included a combination of environmental and ecological factors, the establishment of a system to transfer energy from the area of primary production (the surface ocean) to that of highest diversity (the sea floor) played a crucial role.

Even though relatively small for a radiodont (FIG), Pahvantia was 10-1000 times larger than any mesoplanktonic primary consumers, and so would have made the transfer of energy from the surface oceans to the deep sea much more efficient. Primary producers such as unicellular algae are so small that once dead they are recycled locally and do not reach the deep ocean. In contrast large animals such as Pahvantia, which fed on them, produce large faecal pellets and carcasses, which sink rapidly and reached the seafloor, where they become food for bottom-dwelling animals.

Amateur enthusiasts provide research gold-dust

The presence of Pahvantia in the Cambrian of Utah has been known for decades thanks to the efforts of local amateur collectors Bob Harris and the legendary Gunther family.

‘This work also provides an opportunity to celebrate the exceptional contribution of local and amateur collectors to modern palaeontology’ explains Stephen. ‘Without their tireless efforts, knowledge, and generosity, thousands of specimens representing hundreds of new species, would not be known to science.’

Bob Harris is rumoured to have turned down a job offer from the CIA, instead opening up a fossil shop and a number of quarries in the spectacular House Range, Utah. He discovered the first specimens of Pahvantia in the 1970s, and donated them to Richard Robison, a leading expert on Cambrian life from the University of Kansas. The Gunther family are famous for their extensive fossil collecting in Utah and Nevada. Over a dozen species have been named in honour of their contributions to palaeontology, as they have shared thousands of specimens with museums and schools over the years. Among these were specimens of Pahvantia which they uncovered between 1987 and 1997. Donated to the Kansas University Museum of Invertebrate Paleontology (KUMIP), these specimens are described for the first time in our study.

‘I visited the KUMIP in the first year of my PhD,’ says Stephen. ‘It was awesome, exploring such a fantastic collection of fossils from the Cambrian of Utah and Nevada.’

The study has produced the most up-to-date analysis of evolutionary relationships between radiodonts. It shows that filter feeding evolved twice, possibly three times in this group, which otherwise essentially comprised fearsome predators such as Anomalocaris canadensis from the Burgess Shale in Canada.

Pahvantia adds to an ever-growing body of evidence that radiodonts were vital in the structure of Cambrian ecosystems, in this case linking the primary producers of the surface waters to the highly diverse fauna on the sea floor. It also shows the importance of museum collections like the KUMIP, and local collectors, such as Bob Harris and the Gunther family, in uncovering new and exciting findings about early animal life.

The article is available from Nature Communications via this link.

A brand new exhibition launches this Sunday, 9 September (1-5pm) at SJE Arts in Oxford, the concert and arts venue based at St Stephen’s House, one of Oxford University’s Permanent Private Halls.

‘Wartime at an Oxfordshire Monastery’ tells the First World War story of the community of monks once based at the site that the college now occupies, focusing on specific individuals associated with the monastery during wartime. As well as including profiles of members of the monastery itself, the exhibition features a local woodcarver and organist and communities of local nuns, explaining the contributions they made to the First World War, both at home and abroad.

Made possible by a National Lottery heritage grant, the exhibition marks the centenary of the First World War. Around 100 local schoolchildren, volunteers, teachers and academics were involved in the project, which was led by academic and local social historian Dr Annie Skinner, with Dr Serenhedd James.

The former monastery has been described as containing some of Oxford’s most interesting ‘hidden heritage’. Now largely hidden from view behind the modern-day façade of the Cowley Road, the stunning G F Bodley-designed church and monastery was once a key focal point in this area of the city.

The exhibition is one of the ways St Stephen’s House hopes to encourage more people to come and enjoy the site, following the successful development of a concert and arts venue in the college church and cloister, SJE Arts.

When: Sunday 9 September, 1-5pm, SJE Arts

Where: SJE Arts, 109a Iffley Road, Oxford OX4 1EH

Amy Kao, PhD student at the Department of Psychiatry, Oxford University, reveals how she represented the UK at the international ActinSpace hackathon as part of an Oxford team which combined talents to take on a social problem.

Hackathons have a reputation as a software-heavy coding event welcoming only those with specific skill sets and domain knowledge in computer science. However, as diversity continues to emerge as a pivotal aspect of success for any project, the ActinSpace (AIS) hackathon invited anyone from any background to come and work up realistic ideas using space technology in innovative ways.

The experience was truly memorable. In the beginning stages at Harwell, Oxfordshire, within 24 hours my team and I proposed a satellite-based artificial intelligence application to address street harassment. We worked through the night, inspired by the knowledge that we could be building a technology that could truly make the world a better place.

Our proposed platform was a navigation app to guide you the safest way home. In order to find the safest route, the app estimates the danger on each road segment. Crime record databases in the UK and US are public and annotate with exact geo-location. These can be used to count the number of incidents on each road segment. Using convolutions neural networks and satellite data, the app could accurately estimate the number of pedestrians going along each road. This forms the technical basis of our platform. Additional features are AI-driven velocity tracking that can be used to identify whether the user suddenly stops moving, starts running or even deviating from the intended route, all of which are unexpected behaviours on a normal walk home. Using vibration or non-visual cues avoids the need to be constantly looking down at a phone making you appear less lost, and a much less of a viable target.

We pitched our product in seven minutes the following day, and won the hearts of the UK judges. This gave us the unique opportunity to represent the UK at the international semi- finals in Toulouse.

This was an enormous event gathering teams from over 30 countries, all with exciting and novel technologies.

The finals competition in Toulouse brought together people from across the world sharing a passion for technology and innovation. However, it also sadly highlighted the lack of diversity and representation that remains.

Amy Kao and Anna Jungbluth, DPhil students at Oxford

Amy Kao and Anna Jungbluth, DPhil students at Oxford The AIS 2018 had 23% female participation, but only one team among the six finalists had a female team member. There has been considerable movement in increasing this number; however, we see it as our social obligation to do our part and encourage our female peers to take part and pursue activities that they didn’t think they could achieve.

The best part of the team was our diversity, where we were five students from five different countries, coming to Oxford to study five extremely different disciplines (computer science, economics, medicine, physics, psychiatry) ranging from fresh undergraduates to seasoned DPhils. The hackathon really was a problem-solving event, not a software-heavy event at all. It provided the opportunity of working with other astute individuals to propose a holistic solution using space technology and creative business models.

The burst of productivity over one 24-hour period can be extremely refreshing. I would really encourage others to take part, particularly if you’re not in any mainstream programming fields, and even more so if you’re part of an underrepresented demographic (e.g. women in STEM). My bachelor’s was in cell and molecular biology, and my postgraduate research degrees were in pharmaceutical science and neuroscience; perhaps as far removed from space technology as you can get, let alone participating in a hackathon! The mentality of industries are shifting from the limiting idea of entering a career based entirely on what you studied in school to a dynamic stage that embraces diversity and different approaches to solving a problem. Domain knowledge can be quickly accumulated, but the courage to pursue something outside your normal comfort zone and the confidence that you have meaningful contributions requires deliberate time and context to be developed. Just give it a try!

MPLS runs an Enterprising Women lunch and learn in week 4 of each term, welcoming all researchers interested in developing of a supportive network of STEM women. Details are always advertised via eship.ox.ac.uk

- ‹ previous

- 66 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria