Features

A twice-weekly academic writing group which was set up for PhD students and early career researchers at Oxford University has been credited with boosting productivity and reducing stress.

The group's founder is Dr Alice Kelly, the Harmsworth Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Rothermere American Institute. In a guest post, she tells the story of the writing group:

'Most people need structure, accountability and discipline if they are to work productively. But this is exactly what disappears when highly qualified, often perfectionistic people start the rewarding but lengthy and lonely PhD process.

This is especially true in the humanities, where, in contrast to the more communal research environment that scientific teams enjoy, study is often solitary. I believe that universities can, and should, do much more to generate a sense of group motivation, camaraderie and peer support among early career scholars in the humanities.

I convene a group of postgraduate students and early career researchers to write together for three hours twice a week. After coffee, I ask everyone to share their goals for the first 75-minute session with their neighbour. Goals must be specific, realistic and communicable, such as writing 250 words or reworking a particularly problematic paragraph. I set an alarm and remind everyone not to check email or social media. When the alarm goes off, everyone checks in with their partner about whether or not they achieved their goal. After a break, we do it again. After our Friday morning sessions, we go for lunch together. And that’s it.

Yet the impact of the group in terms of writing productivity, reducing student stress and promoting a sense of community has been profound – beyond what even I had anticipated when I first introduced these sessions at the interdisciplinary Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) in October 2015. Since its beginning, the group has been enormously popular and is always oversubscribed. I have become convinced that such writing groups are an affordable and highly effective way of reducing early career isolation and improving mental health, and could be implemented more widely.

Participants reported the positive effects in two anonymous surveys for our humanities division. They value the sessions’ imposition of routine, realism about expectations and embodiment of the principle that thinking happens through, not before, writing (known as the “writing as a laboratory” model). Respondents were pleasantly surprised at their own productivity. One said: “I never thought I could accomplish so much in one hour, if I really committed, without interruptions”.

Another said: “It seems I lost the fear of finishing things when I was surrounded by other people.” Participants also reported adopting their newly established good habits outside the sessions.

Most evident, however, was respondents’ improved sense of morale and peer support. One noted that “the PhD can be such an isolating experience; it’s very calming to come to a place where, twice a week, we’re reminded that working independently doesn’t have to mean working alone”. Another referred to the group as “an invaluable resource that should be mandatory for all PhDs”.

The writing group offers, for six hours a week, what most workers get every day: a start time, a stop time and peer pressure not to procrastinate on the internet. Over a term’s worth of attendance, this produces serious results.

One participant had “rewritten a draft thesis chapter, written a conference abstract, edited two reviews for an online publication, finished two book reviews and edited several chapters of a volume”.

My role in the group varies between friend, peer, disciplinarian, mentor, stand-in supervisor, and a regular fixture offering some stability and continuity. If people don’t show up, I hold them accountable. If they are struggling with a piece of writing, I talk them through it.

The group has unexpectedly become an informal forum for all the academic questions we’re not sure who else to ask about, and has therefore had a serious impact on pastoral care through peer support.

As someone who worked long hours through the four years of my PhD – in exhausting periods of “binge writing” and unnecessarily time-consuming revisions – I am now a vocal advocate of short bursts of focused attention and writing as a routine practice, with mandatory time off from academic work.

One survey respondent noted that the group “has given me the sense that I have a working week and am not expected to work 24/7; it has helped me treat my degree as a job”.

As the group has developed, I have investigated strategies to make the sessions more effective. One idea was to organise a manual or sensory activity (colouring in or listening to music, for instance) during the break; another was to make participants set regular goals on index cards and to add a gold star when they achieve them.

Writing marathons – two three-hour sessions, separated by lunch – are useful for meeting end-of-term deadlines. The combination of accountability and reward (group celebrations at the end of a goal period, or when somebody submits their dissertation) motivates participants both to push themselves and to be pleased with their progress.

There is surprisingly little literature on the benefits of writing in group settings. Very helpful texts, such as Eviatar Zerubavel’s The Clockwork Muse (1999) and Paul Silvia’s How to Write a Lot (2007), advocate scheduled writing, goal setting and monitoring progress, but do not address the high levels of self-discipline needed for regular independent writing that a group provides.

Meanwhile, the literature considering writing groups, such as Rowena Murray and Sarah Moore’s The Handbook of Academic Writing (2006) or Claire Aitchison and Cally Guerin’s volume Writing Groups for Doctoral Education and Beyond (2014), promotes them for collaborative writing or peer review purposes, rather than improved morale and community.

Amid mounting demands for “outputs” and increasing evidence of chronic stress and mental health problems among academics, having an academic writing group at every university could be a simple yet powerful way of making the task of writing more productive and rewarding for the next generation of scholars.'

This article was originally published in the Times Higher Education.

The decibel level was raised at a sound-themed event at the Ashmolean Museum on Friday night (3 March).

SUPERSONIC was the latest event in the Museum's popular 'LiveFriday' series, and it involved Oxford University’s Music Faculty, The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), Oxford Contemporary Music, and Oxford Brookes University’s Sonic Art Research Unit (SARU).

On the night, there were bite-sized lectures from many academics from the University’s Music Faculty, including Professor Eric Clarke.

‘LiveFriday’s ‘Supersonic’ theme was a great opportunity to showcase a whole variety of fascinating activities in and around sound, sound-art and music, involving the Oxford Faculty of Music, Oxford Contemporary Music and other guests and contributors,’ says Professor Clarke.

‘There are no human cultures without music - so music is as defining of what it is to be human as anything else. What better way to explore and acknowledge that fantastic human attribute than by coming to the wonderful Ashmolean Museum, and hearing, seeing and participating in all the musical performances, workshops and talks that will be on offer.’

Professor Clarke told an attentive audience about his new research into the link between music, empathy and cultural understanding. ‘Our research demonstrated that just listening to the music of other cultures can have significant effects on people’s more general cultural attitudes,’ he said.

There were performances from student electronic ensembles such as Sal Para (Tremor Recordings) and Wandering Wires.There were sound art installations throughout the museum, and an interactive songwriting workshop.

Perhaps the most eye-catching part of the event was a ‘swinging’ concert grand piano suspended high above the ground in the Ashmolean’s atrium.

As part of our Women in Science series, ScienceBlog meets Professor Tamsin Mather, a volcanologist in the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford University. She discusses her professional journey to date, including recent work with the education initiative Votes for Schools, and why science is the best game around.

What is a typical day in the life of a volcanologist like?

Volcanology is incredibly varied, so there is no typical day. Some days I am out in the field, gathering samples from volcanoes and others I’ll be in the lab, giving lectures, or out in the community, encouraging people to take an interest in science.

What has your professional highlight been to date?

There have been lots, but one of the most exciting was finding fixed nitrogen in volcanic plumes in Nicaragua.

All living things need nitrogen to survive. Although Earth’s atmosphere is mainly made up of nitrogen, its atoms are very tightly bonded into molecules, so we can’t use it. To do so, you need something to trigger their separation. For example, when lightning strikes, the heat prompts atmospheric nitrogen to react with oxygen, forming nitrogen oxides or “fixed nitrogen”. We discovered that above lava lakes, volcanic heat can have the same effect.

Volcanology is incredibly varied. Some days I am out in the field, gathering samples from volcanoes and others I’ll be in the lab, giving lectures, or out in the community, encouraging people to take an interest in science.

Why was the discovery so interesting?

The research shows how volcanoes have played a role in the evolution of the planet and the emergence and development of life.

But that particular trip looms large in my memory because we were robbed while getting the data. I remember it vividly, we had waited all day at the crater edge for the plume to settle, but the sun set before we had a chance to take our measurements. We went back to the national park early the next day, before the security guards arrived, and got robbed at gun point. In retrospect we should have known better, but excitement got the better of us. A terrifying experience but thankfully no one got hurt. We didn’t even get great data that day in the end.

How did you come to specialise in volcanology?

By mistake. When applying for my PhD I put ocean chemistry as my first choice, but I was stumped for my second choice, so browsed the list of topics and the atmospheric chemistry of volcanic plumes stood out to me. I got more and more excited as I read about it, and ended up switching it from my second to first choice. I haven’t looked back.

Do you think being a woman in science holds any particular challenges?

The statistics bear it out - we are still in the minority. There are lots more women in more junior levels now and that will filter through eventually. I definitely would have appreciated more visible female scientist role models when I was younger, but I think the perception of science as a male pursuit is eroding.

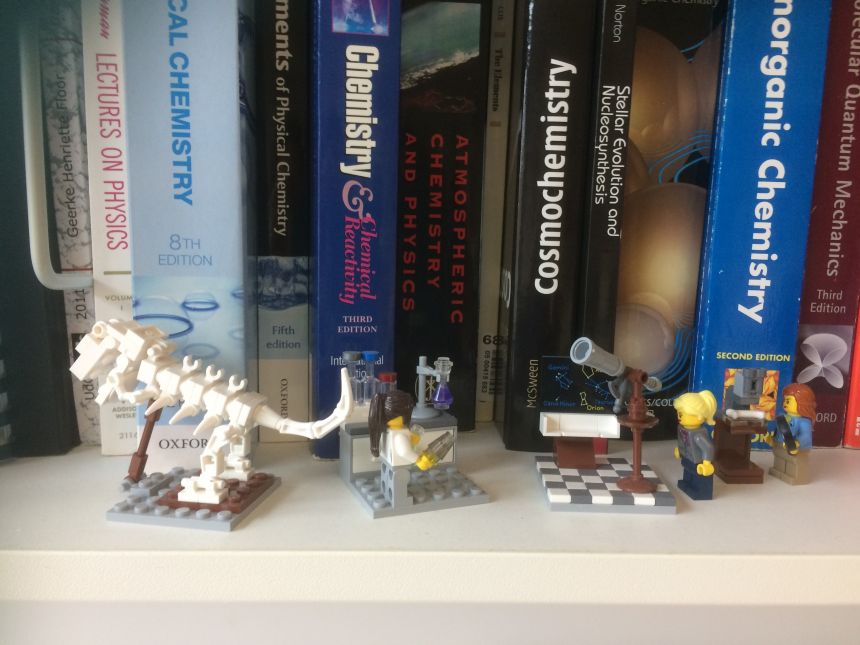

For instance, I used to love Space LEGO, but there wasn’t much diversity in the astronaut characters that came with the kits then. Now, my primary school age daughter loves it too, and the kits are much more diverse. I even have the all-female Research Institute kit in my office. The landscape has changed a lot in the last 20 years, but there is still more to be done.

There isn’t just one solution. Whether in relation to gender or ethnic diversity in science, it is a multi-component problem. If someone is the only woman or ethnic minority in their group, they may feel there is no future role for them. There are so many influencing factors in this situation and they are not all easily articulated or solved.

Science is the best game around. You could be building bridges, curing a disease, developing new apps or climbing a volcano – the world is your oyster. I get paid to discover new things about our planet every day, how cool is that?!

What do you think can be done to encourage more diversity in science?

One of the key challenges for women in academia is the transition from PhD student, to post doc level and on to permanent faculty member. Often at that stage scientists have to relocate frequently. Some of my female contemporaries found this difficult and wanted more stability. Maybe they wanted to be close to a partner, or were thinking about having children. That is not an easy problem to solve and it can be difficult for men too.

There are things that can be done to make this journey easier. Programmes that provide flexible working patterns for outstanding scientists, like the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship scheme, work well, for instance.

The all-female LEGO Research Institute collection, sits in pride of place on Professor Mather's office bookshelf, as a testament to how far gender bias in science has evolved. Copy Right: Tamsin Mather

The all-female LEGO Research Institute collection, sits in pride of place on Professor Mather's office bookshelf, as a testament to how far gender bias in science has evolved. Copy Right: Tamsin MatherWhat are you working on at the moment?

We are studying the volcanoes of the Rift Valley in Ethiopia. Little is known about the history of these volcanoes and how often they erupt. But by measuring the layers of ash that have deposited around them, we can learn more about past and present volcanic activity. It’s possible these volcanoes could be used as energy sources in the future and we are investigating their potential for geothermal development.

How did you get started in science?

I always found it fun and really wanted to be an astronaut, but when I was seven I had an ear operation which killed that dream.

How did you come to be involved in Votes for Schools, the education initiative supporting children to have informed opinions?

It’s a great way to get young people thinking critically about the difference between opinions and facts. We have to empower young people and make sure they realise why having a voice matters. It is important to have an informed opinion, no matter your age. I was asked to join the Votes for Schools team, visiting Packmoor Ormiston Academy to talk about being a female scientist and to launch the primary school version of the scheme.

How did the children respond to your question, ‘Do we need more female scientists and engineers?’

The majority (61%) felt that there were not enough female scientists. The statistics of under-representation, arguments about diverse teams performing better, and the importance of engaging the whole of society in science were key here. Those that responded no, felt women have the right to choose what they want to be, a scientist or otherwise. Cultural background came into play as well, with some saying that women should stay at home.

What were your main takeaways from working with the initiative?

Questions like ‘do you ever work on metamorphic as well as igneous rock?’ really surprised me, and the enthusiasm of staff and children alike was fantastic. They really understood the issues and were not afraid to express their opinions. Technology is so central to our lives now, compared to when I was at school. Smart phones and computer games have become key to how we socialise and have fun. Science and technology are certainly not just for geeks anymore!

What advice would you give to someone considering a career in STEM?

Do it! It’s the best game around. There are so many doors that a career in STEM opens for you. You could be building bridges, curing a disease, developing new computer games or apps or climbing a volcano – the world is your oyster. I get paid to discover new things about our planet every day, how cool is that?!

Dr Matthew S. Erie, who is Associate Professor of Modern Chinese Studies at the Oriental Institute, has been named a Public Intellectual Fellow by the National Committee on US-China Relations (NCUSCR).

The Public Intellectuals Program (PIP) was launched in 2005 to nurture the next generation of China specialists who have the ability to play significant roles as public intellectuals.

PIP Fellows gain access to senior policymakers and experts in both the United States and China, and to the emerging business and nonprofit sectors in China, as well as the media.

Dr Erie says: ‘I’m honoured to be named a PIP Fellow by the NCUSCR. As a PIP Fellow, I am fortunate to engage in a number of workshops in the U.S. and in China to create synergies between the academy and policy circles in the U.S. and China.

'There is a lot of work to do to increase education on and general awareness of Islam and China. The NCUSCR, and PIP in particular, provides a platform for scholars to hone their message to reach wider publics.

'One of the key priorities to me is to close the gap between those who either promote or fall prey to anti-Muslim or anti-Chinese sentiment, on the one hand, and those who work in the academy, on the other hand.'

Being named a PIP Fellow helps China scholars to broaden their knowledge about China's politics, economics, and society, and encourages them to use this to inform policy and public opinion.

Last year, Dr Erie published ‘China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law’, which looks at how shari'a (Islamic law and ethics) is implemented among the Hui, who are one of 10 officially recognised ethnic groups in China. Being a PIP Fellow could help him to get his research across to broader audiences in China and the US.

'Islamophobia, in particular, has emerged as one of the defining social pathologies of the twenty-first century,' he says. 'We can see its impacts from Brexit to Trump’s America to the ascendance of nationalist political parties in Western Europe. Islamophobia is not just a “Western” phenomenon but over the past year or so has intensified in places like China.

'One common misperception fuelling Islamophobia is that shari’a (a term heavily debated by Muslims but which generally means “Islamic law and ethics”) is somehow creeping into state law. In my book, I argue that Chinese Muslims (Hui) practice a form of shari’a with soft edges, and that the very informality of shari’a in China allows for both Hui and state actors to make arguments based on shari’a for their notion of the “good”.

'In other words, Hui do not impose shari’a over non-Muslims, but rather, Hui and the state alike make use of the authorities, texts, and symbols of shari’a as material to fashion their ideas of society. While such constructions create conflicts, the book illustrates that shari’a can also provide a “middle ground” between Muslims and non-Muslims.

'By focusing on the case of China, a country that is commonly perceived as either “authoritarian” or “lawless,” I hope to demonstrate the adaptability of shari’a. While it can create conflicts with state law, it can also facilitate economic development, contacts with other developing states, and ethical action."

Dr Erie explained his research in more detail in an interview with the New York Times last year.

More information about the programme can be found here.

Mrs Mica Ertegun has been made an honorary Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE), an award conferred by HM The Queen for her services to philanthropy, education, and British-American cultural relations.

The award recognises Mrs Ertegun’s support for humanities postgraduate education in the UK and in particular her establishment of the Mica and Ahmet Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities - open to students worldwide - at Oxford University in 2012.

Mrs Ertegun has endowed the university with substantial funding for post-graduate research in the humanities, under the Ertegun Programme, which will include the endowment of graduate scholarships in perpetuity. This is the single largest philanthropic gift for the humanities at the University of Oxford.

Since 2012, Mrs Ertegun’s gift of £26 million has enabled 45 leading humanities scholars from 16 countries around the world to study and research at Oxford University. Among those Ertegun Scholars who graduated in 2015, 80% received distinctions. Ertegun Scholars’ research areas have included literature, history, music, archaeology, art history, ancient history, Asian studies, Middle Eastern studies, and medieval and modern languages.

Born in Romania, Mrs Ertegun is a citizen of the USA, and received her CBE in a special ceremony in New York. Antonia Romeo, British Consul General New York and Director-General Economic and Commercial Affairs USA, said, “The awarding of Mica Ertegun’s CBE recognizes her exceptional transatlantic philanthropic activities, and her major contributions to British-American cultural relations. These charitable efforts and initiatives, especially via the Mica and Ahmet Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities at Oxford University, are key to the growth of generations of future global academic leaders.”

Established in 2012, the Mica and Ahmet Ertegun Graduate Scholarship Programme in the Humanities at Oxford University provides recurrent annual funding for a population of 15 – 30 graduate students, known as Ertegun Scholars. In addition, Mrs Ertegun has overseen the conversion of an Oxford University building into an academic base for the students, Ertegun House, and established an annual lecture programme.

More information on this story can be found here.

More information about the Ertegun Scholarships and life at Ertegun House can be found here.

- ‹ previous

- 103 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria