Features

Cultures and Commemorations of War is an interdisciplinary seminar series that explores the practices and politics of war memory across time. Organised by Dr Alice Kelly, Harmsworth Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Oxford’s Rothermere American Institute, the series was initially funded by a British Academy Rising Stars Engagement Award.

The next event, held on Thursday 9 May, is the fifth in the series and focuses on the interplay between art, war and memory, with a keynote speech from the renowned graphic novelist Joe Sacco. Dr Kelly, who is also a Junior Research Fellow at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, talks to Arts Blog about the event...

What topics will this seminar explore?

The purpose of this interdisciplinary seminar is to explore the artistic and visual representation of war in many different contexts. Over the course of the day, we will hear from a range of academics (from professors to PhD students), artists and practitioners working on the artistic representation and memory of many different conflicts. In the morning there will be short talks on a new First World War video game, on art after Auschwitz, and on the political cartoons of the Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali (assassinated in 1987). In the afternoon we will hear about a project which links the Belgian refugee crisis in the First World War with contemporary refugees, and a project to photograph murals in Northern Ireland through the Troubles.

What role does art play in the representation of war?

Art and war have a complex relationship. In one way, the two are opposite: art is creative, war is destructive, but obviously it’s more complicated than that. Art, perhaps more than other media, has an immediacy which makes it highly effective in telling the story of a war. Art in wartime can promote war through propaganda, or it can protest against war. War inspires art, but it can also be looted in wartime or destroyed by war – think of, in recent times, the temples destroyed in Palmyra, Syria. Art can enable us to remember violence, recording the experience of people who may be forgotten by the historical record, and to rewrite the history of war, but it can also facilitate the forgetting of violence by censorship and photo manipulation. After a war, art can enable people to recover. There are also the complicated ethics of war art – what can be depicted and what can’t? What is reportage and what is exploitation? What constitutes ‘war art’? We’ll be thinking about some of these issues at our seminar.

Tell us about Joe Sacco’s significance in this area.

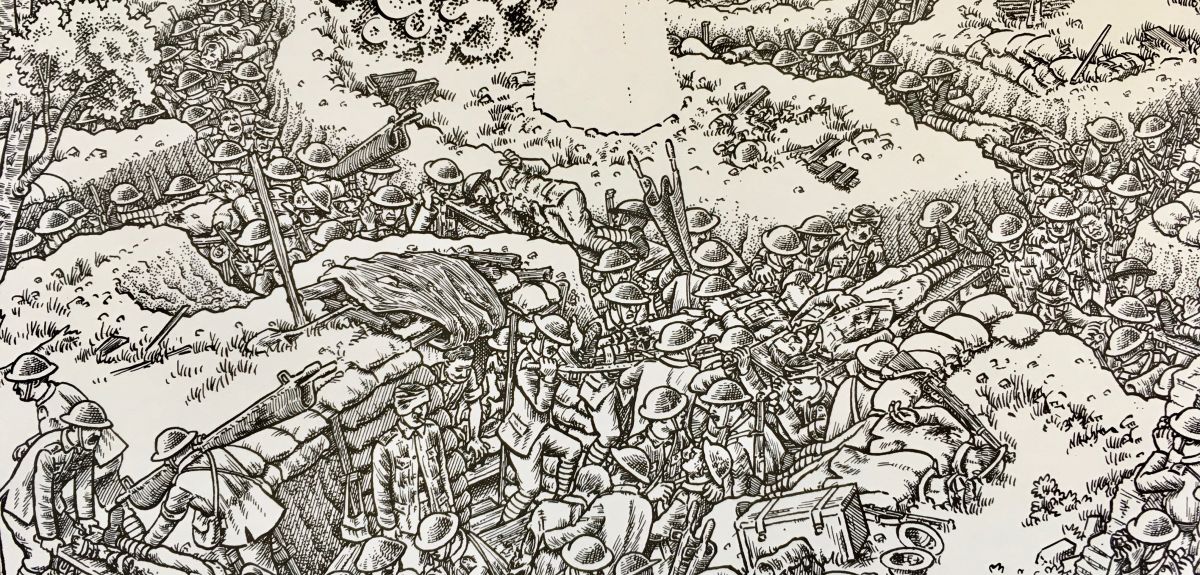

Joe is an award-winning cartoonist who combine eyewitness journalism and art, and is a pioneer within the genre of comics journalism. He is particularly known for representing conflict and violence, and their cultural and social memory. Some of his best-known books, for example Palestine (2001) and Footnotes in Gaza (2009), have focused on the Israel-Palestine conflict, while in books such as Safe Area Goražde he focuses on the Bosnian War. His epic 24-foot depiction of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, called The Great War (2013), should be seen by everyone thinking about the war. The scope of Joe’s reportage and his ability to provide panoramic scenes while paying meticulous attention to detail, combined with his humane and sensitive journalism, constitute a body of work which exemplifies the key themes of this CultCommWar seminar.

What else have you covered in this seminar series?

This is the fifth workshop in the seminar series. Our previous four events have covered a wide range of topics related to the practices and politics of war memory across time. In the first year, the series was funded by a British Academy Rising Stars Public Engagement Fellowship. In the two events held in Oxford and one at Imperial War Museum London, our keynote speakers were the journalist and writer David Rieff, the academic Marita Sturken, and the Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller (who told us about the process of creating We’re Here Because We’re Here, his Somme centenary piece). Our first event this academic year focused on American wars and American memory, and featured the anthropologist Sarah Wagner. Across the series, our conversations have considered the myriad ways that war has been remembered in unofficial and official contexts, from video games to baseball caps (shared between Vietnam vets); from old and new memorials to volunteers dressed as soldiers in Paddington station.

Most of the events feature a morning roundtable led by postgraduates and early career researchers, where the chairs are set in a circle to encourage an open and democratic exchange of ideas. I wanted to move away from the set structure of a conference and I think of these events more like a kind of thinktank, where audience members are encouraged to participate as much as possible.

You can read short pieces about the series on the British Academy website and the Oxford Arts Blog, and I wrote a short article for Times Higher Education on how the series particularly champions emerging and early career scholars in these types of events.

There are still a few places available at the event:

To register for the full-day workshop, please click here.

To register ONLY for the talk by Joe Sacco, please click here.

Eduardo Lalo, Professor of Literature at the Faculty of General Studies at the University of Puerto Rico, and an artist and author, has been appointed as Global South Visiting Fellow at TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities).

Eduardo Lalo's literary oeuvre comprises novels, essays, poetry, graphic art and fascinating hybrids of all of these. He is the author of the novels La inutilidad (Uselessness, 2004), Simone (2015), and Historia de Yuké, which has just been published by Ediciones Corregidor in Argentina. For Simone, he was awarded the Rómulo Gallegos International Novel prize - an exceptional honour granted to the likes of Gabriel García Márquez for One Hundred Years of Solitude (1972) and Roberto Bolaño for The Savage Detectives (1999). Uselessness and Simone have both been translated to English and published by the University of Chicago Press.

The Global South visitor programme, which sits in TORCH, is part of a wider aim to diversify the curriculum in Oxford’s humanities departments. The scheme is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and is part of TORCH’s ‘Humanities & Identities’ series.

Mr Lalo said: ‘I am looking forward to joining the Oxford academic community and working with Dr María del Pilar Blanco from the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages. I am grateful for the opportunity to be included in conversations on curriculum diversification and look forward to sharing my work and experiences with students, academics and staff.’

María del Pilar Blanco, Associate Professor in Spanish American Literature, is sponsoring Mr Lalo’s term at the University. She said: ‘I am pleased to see Eduardo join us here in Oxford. He is one of the most important cultural figures working in Puerto Rico today. He will offer our academic community a much-needed, urgent perspective on contemporary Caribbean arts and politics, as well as a unique view on hemispheric American and transatlantic cultural, political and social exchanges.’

Through the Global South visitor scheme, academics from countries in the Global South are hosted by a University of Oxford academic for one or more terms. The programme also provides role models and increases awareness around diversity and inclusivity across the wider University. The scheme builds on and reinforces existing links between Oxford (including TORCH), Mellon and universities in the Global South.

Mr Lalo will be based at Oxford’s Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and Trinity College during Trinity Term 2019.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) has announced that Caster Semenya and other athletes with disorders of sex (DSD) conditions will have to take testosterone-lowering agents in order to be able to compete. Julian Savulescu, Uehiro Professor of Practical Ethics in Oxford's Faculty of Philosophy, writes in response to this decision...

Reducing the testosterone levels of existing intersex female athletes is unfair and unjust.

The term intersex covers a range of conditions. While intersex athletes have raised levels of testosterone, its effect on individual performance is not clear. Some disorders which cause intersex change the way the body responds to testosterone. For example, in androgen insensitivity syndrome, the testosterone receptor may be functionless or it may be partly functional. In the complete version of the disorder, although there are high levels of testosterone present, it has no effect.

As we don’t know what effect testosterone has for these athletes, setting a maximum level is sketchy because we are largely guessing from physical appearance to what extent it is affecting the body. It is not very scientific. We simply don’t know how much advantage some intersex athletes are getting even from apparently high levels of testosterone.

It is likely that many winners of Olympic medals and holders of world records in the women’s division will have had intersex conditions historically. It is only recently we have become aware of the range of intersex conditions as science has progressed.

These intersex women have been raised as women, treated as women, trained as women. It is unfair to change the rules half way through their career and require them to take testosterone-lowering interventions.

It is a contradiction that doping is banned because it is unnatural, risky to health, and reduces solidarity. But in these cases they want to force a group of women to take unnatural medications, with no medical requirement, in order to alter their natural endowments. Elite sport is all about genetic outliers. Cross-country skier Eero Mantyranta won seven Olympic medals in the 1960s, including three golds. He had a rare genetic mutation that means the body creates more blood cells. The oxygen carrying capacity can be up to 50% more than average. This is a huge genetic advantage for endurance events like cross-country skiing. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) says “the spirit of sport is the celebration of the human spirit, body and mind”, but in this case, the rules seek to limit and quash bodies that don’t fall into line with our expectations.

It is true that the rules of sport are arbitrary. What defines man and woman will always have borderline cases. But it is imperative these individuals are not unfairly disadvantaged. It is unfair to take away a person’s life and career because you choose to redefine the rules.

CAS agreed that the rules are unfair, but found the unfairness justified: “The panel found that the DSD regulations are discriminatory but the majority of the panel found that, on the basis of the evidence submitted by the parties, such discrimination is a necessary, reasonable and proportionate means of achieving the IAAF’s [International Association of Athletics Federations] aim of preserving the integrity of female athletics in the restricted events.”

Yet there is another option: to implement the rules prospectively by allowing a “grandmother” clause for existing athletes who identify and were raised as women. Then testing for new athletes could take place early – as soon as puberty is complete – to identify athletes who would come under the DSD definition. Affected athletes could make an informed choice about continuing to compete at the cost of being required to take testosterone-lowering agents. This would still deny them the opportunity of competing to their full potential, but it would at least prevent individuals from investing their lives in a sport they would either not want to or be able to compete in.

Intersex conditions can restrict people’s life options. In many cases, it is not possible to have a biologically related child or carry a pregnancy. Unfortunately, it can still carry stigma and discrimination (indeed CAS agree this is an example of it). One possible upside is an advantage in sports. This should not be denied.

Sport is based on natural inequality. If this is of concern to the authorities, I have argued that physiological levels of doping should be allowed. This would allow all women to use testosterone up to 5nmol/L, as can occur naturally in polycystic ovary syndrome and which the IAAF has considered an upper limit for women with intersex conditions. This would also reduce or eliminate the advantage some intersex athletes hold.

The rules of sports are arbitrary but they should not be unfair. Changing the rules to exclude a group of people who signed up under the current rules is unfair. A change for future generations of athletes would be less unfair, but I believe that it will make for a less interesting competition and will still disadvantage some women.

There is no fairytale ending to this story. Someone will be a loser. But that is always the case in sport.

The 25 of April is World Malaria Day - a good time to take stock of progress towards dealing with one of the great historical global scourges.

Malaria is caused by a tiny parasite transmitted to humans by the bite of certain sorts of (Anopheline) mosquitos. It occurs though the tropics and subtropics. Historically is has caused so many deaths that it has been one of the most powerful selective forces acting on human evolution.

At the turn of this century malaria was rightly described by many as a ‘disaster’: resistance to drugs used in treatment was widespread and estimates of deaths were in millions a year. There was a sense of national and international paralysis. In response to this dire situation came a whole set of initiatives, including declarations by heads of states the initiation of new public private partnerships and the launch of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and malaria. Often such efforts are greeted with a certain amount of scepticism but in this case they marked the beginning of a log order rise in global investment in malaria control and a truly remarkable change in the global malaria situation.

Over the next 15 years malaria reduced dramatically in almost all parts of the world accompanied by an incredible 60% reduction in malaria death rates. In large part this was due to the widespread deployment of effective new drugs, the so called artemisinin combinations and the use of bed nets impregnated with insecticide Encouraged by the possibilities many began to call for a new campaign of global malaria eradication. Others were concerned that this was hubristic, given the biological and social complexity of malaria. The WHO set out in 2015 a Global Technical Strategy, which while disappointing some by not calling for eradication in any short time frame, was in fact very ambitious in aiming at a 90% reduction in malaria deaths by 2030 and at least 35 countries to have achieved elimination.

Over the last few years we have come to a more realistic and nuanced appreciation of the global position. In areas of lower transmission progress toward the elimination targets is on track but at the other end of the spectrum malaria remains a major cause of death in high burden countries. 75% of the worlds estimated 435,000 deaths each year occur in just 11 countries, ten of them in Africa and the eleventh being India. Here progress is in danger of stalling without concerted political and societal action. Against this background there is also concern about emerging drug and insecticide resistance and static levels of international funding. On the more optimistic side there is exciting progress towards potential new tools including drugs, vaccines and ways of genetically modifying mosquito populations.

So on malaria day 2019 we can reflect both on the massive progress over the last 19 years and but also on the considerable challenges ahead. It is a matter of pride that researchers from many parts of Oxford University and especially the major overseas collaborating programmes in south East Asia and Africa have played a central role in the many of the developments that have contributed to the progress described above.

Kevin Marsh is Professor of Tropical Medicine at the Nuffield Department of Medicine.

By Penny Mealy, Thom Wetzer and Matthew Ives

Search online for ‘climate change’ and ‘tipping points’, and you will find some scary results. Melting Ice-sheets, the collapse of the Atlantic thermohaline circulation, the permafrost methane ‘time bomb’ and the dieback of the Amazon that threaten to exacerbate the climate crisis and cause global warming spiralling out of control.

But what if we could leverage similar tipping point dynamics to solve the climate problem? Like physical or environmental systems, socioeconomic and political systems can also exhibit nonlinear dynamics. Memes on the internet can go viral, loan defaults can cascade into financial crises, and public opinion can shift in rapid and radical ways.

Research into such positive socio-economic tipping points is underway at the Institute for New Economic Thinking for the Oxford Martin School Post-Carbon Transitions Programme, headed by Professors Doyne Farmer and Cameron Hepburn. In an article just published in Science, the team outline a new approach to climate change that seeks to identify areas in socio-economic and political systems that are ‘sensitive’ - where a modest, but well-timed intervention can generate outsized impacts and accelerate progress towards a post-carbon world.

Sensitive Intervention Points (SIPs)

These “Sensitive Intervention Points” – or SIPs – could trigger self-reinforcing feedback loops, which can amplify small changes to produce outsized effects. Take, for example, solar photovoltaics. As more solar panels are produced and deployed, costs fall through “learning-by-doing” as practice, market testing and incremental innovation make the whole process cheaper.

Cost reductions lead to greater demand, further deployment, more learning-by-doing, more cost reductions and so on. However, the spread of renewables isn’t just dependent on technology and cost improvements. Social dynamics can also play a major role. As people observe their neighbours installing rooftop solar panels they might be more inclined to do so themselves. This effect could cause a shift in cultural and social norms.

Financial markets are another key area where SIPs could help accelerate the transition to post-carbon societies. Many companies are currently failing to disclose and account for climate risks associated with assets on their balance sheet. Climate risk can entail physical risks, caused by extreme weather or flooding. They can also entail the risk of assets such as fossil fuel reserves becoming stranded as economies transition to limit warming to 1.5℃ or 2℃, when such resources are no longer valuable.

Most of the world’s current fossil fuel reserves can’t be used if the world is to limit warming and they become effectively worthless once this is acknowledged. By not accounting for these risks to fossil fuel assets, high-emission industries are effectively given an advantage over low-carbon alternatives that shouldn’t exist. Relatively modest changes to accounting and disclosure guidelines could make a significant difference.

If companies are required to disclose information about the climate risks associated with their assets – and if such disclosure is consistent and comparable across companies – investors can make more informed decisions and the implicit subsidy enjoyed by high-emission industries is likely to rapidly disappear.

Opportunities for triggering SIPs in a given system can also change over time. Sometimes “windows of opportunity” open up, where very unlikely changes become possible. A key example in the UK was the political climate in 2007-2008 which enabled the 2008 UK Climate Change Act to pass with near unanimous support. This national legislation was the first of its kind and committed the UK to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% relative to 1990 levels by 2050.

The act also created a regular ratcheting cycle which encourages more ambitious future climate action. Since 2008, emissions in the UK have fallen dramatically. However, the UK Climate Change Act’s influence beyond the UK is also significant as it encouraged similar legislation in other countries, including the Paris Agreement, which contains the same self-reinforcing ratcheting mechanism.

Using SIPs for rapid change

Thinking about SIPs in policy and business could accelerate the post-carbon transition – but much work lies ahead. The first step is to systematically identify potential SIPs and the mechanisms by which they can be amplified.

Unfortunately, traditional economic models commonly used to evaluate climate policy are poorly equipped to do this, but new analytical methods are increasingly being used in policy.

These new methods could provide more accurate insights into the costs, benefits and possibilities of SIPs for addressing climate change. As SIPs could be present in all spheres of life, experts in social and natural sciences will need to work together.

The window to avert catastrophic climate change is closing fast, but with intelligent interventions at sensitive points in the system, we believe success is still possible. Since the stakes are so high – and the time frame so limited – it is not possible to chase every seemingly promising idea. But with a smart, strategic approach to unleashing feedback mechanisms and exploiting critical windows of opportunity in systems that are ripe for change, we may just be able to tip the planet onto a post-carbon trajectory.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Conversation.

- ‹ previous

- 57 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria