Features

Adapted from an article by Exzellenzcluster Topoi.

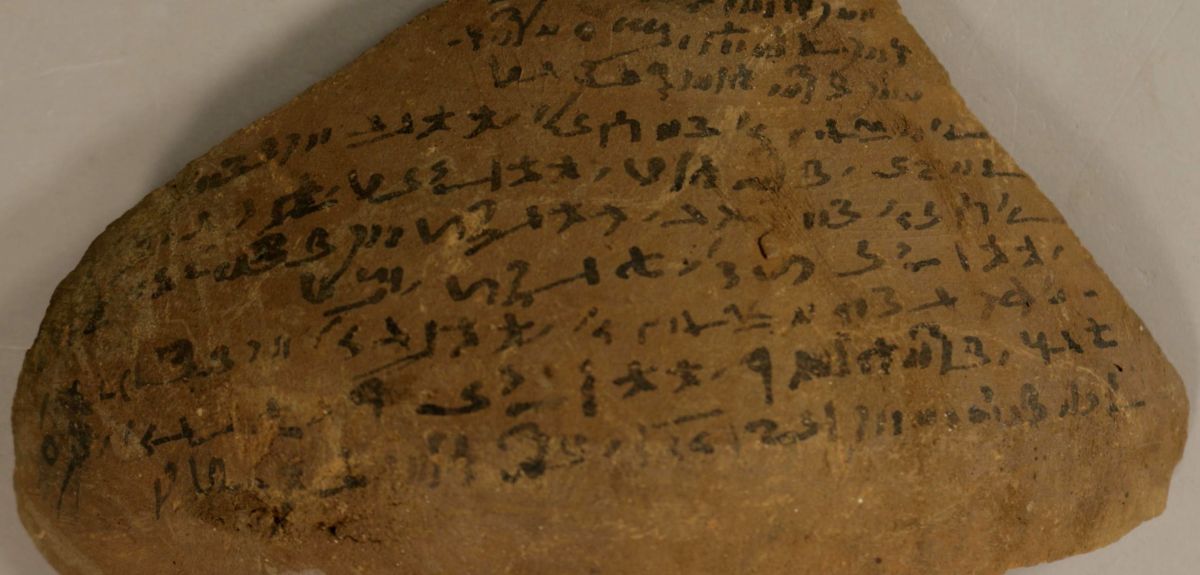

Egyptian astronomers computed the position of the planet Mercury using methods originating from Babylonia, finds a study of two Egyptian instructional texts from Oxford's Ashmolean Museum. The study was carried out by Mathieu Ossendrijver, a historian of ancient science at Humboldt University Berlin and Exzellenzcluster Topoi, and Andreas Winkler, an Egyptologist at Oxford University's Faculty of Oriental Studies. The instructional texts date to 1-50 AD and are written in the Demotic language, a late stage of ancient Egyptian, on two 'ostraca' (potsherds, or broken pieces of ceramic material). They are the only known texts from Greco-Roman Egypt with instructions for computing astronomical phenomena with Babylonian methods.

The instructions correspond exactly to methods invented in the ancient state of Babylonia several centuries earlier (400-300 BC). Surprisingly, the ostraca employ a mathematical formulation not found in Babylonian texts but whose existence has long been suspected by historians of astronomy. The ostraca prove that native Egyptian scholars were as competent in Babylonian astronomical computation as their colleagues writing in Greek, suggesting a more important role for native Egyptian scholars in the transmission of Babylonian astronomy to Greco-Roman Egypt than previously thought.

By the early second century BC, Babylonian astrology and astronomy had spread to Egypt. Like their Babylonian colleagues, Egyptian astrologers began to produce horoscopes in order to determine the fate of a newborn. The production of a horoscope required computing the zodiacal positions of the Moon, the Sun and the five planets known in antiquity: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Both Demotic horoscopes and Greek horoscopes have been found in Egypt, and in 1999 the American historian of astronomy Alexander Jones proved that some Egyptian astrologers writing in Greek were using Babylonian methods. But until now little has been known about the computational methods of the native Egyptian astrologers writing in Demotic.

The two newly identified Demotic texts with computational instructions shed new light on the mathematical skills of the native Egyptian astrologers. Both ostraca contain instructions regarding three distinct Babylonian algorithms. Each of them is concerned with a particular phenomenon of Mercury: its first appearance as an evening star, its first appearance as a morning star, or its last appearance as a morning star. The inscriptions offer the first unequivocal proof that native Egyptian astrologers, like their colleagues writing in Greek, were capable of computing positions of Mercury, a planet with a comparably complicated motion, using Babylonian methods. An analysis of the instructions suggests that the native Egyptian scholars adapted these methods before their colleagues writing in Greek, as well as independently of those colleagues. First, the ostraca predate all known Greek tables for Mercury that were computed with these methods, and are in fact the only instructional texts with Babylonian astronomy that have been found in Egypt thus far. Second, they use a Babylonian loanword for 'degree', while the astrologers writing in Greek used a Greek word for this.

A surprising aspect of the instructions is that they employ a mathematical formulation that is unknown from Babylonia. While the Babylonians directly computed the variable distance travelled by Mercury along the zodiac – for example, between two occurrences of its first appearance as an evening star – the Egyptian scholars first divided the zodiac into tiny steps of variable length. The distance travelled by Mercury was then obtained by counting off a fixed number of these steps, with identical results to those obtained by their Babylonian counterparts. In 1957, the mathematician Bartel van der Waerden first suggested the existence of this alternative formulation. While it has not yet been identified in any Babylonian text, we now see it in these two Demotic texts written by native Egyptian scholars.

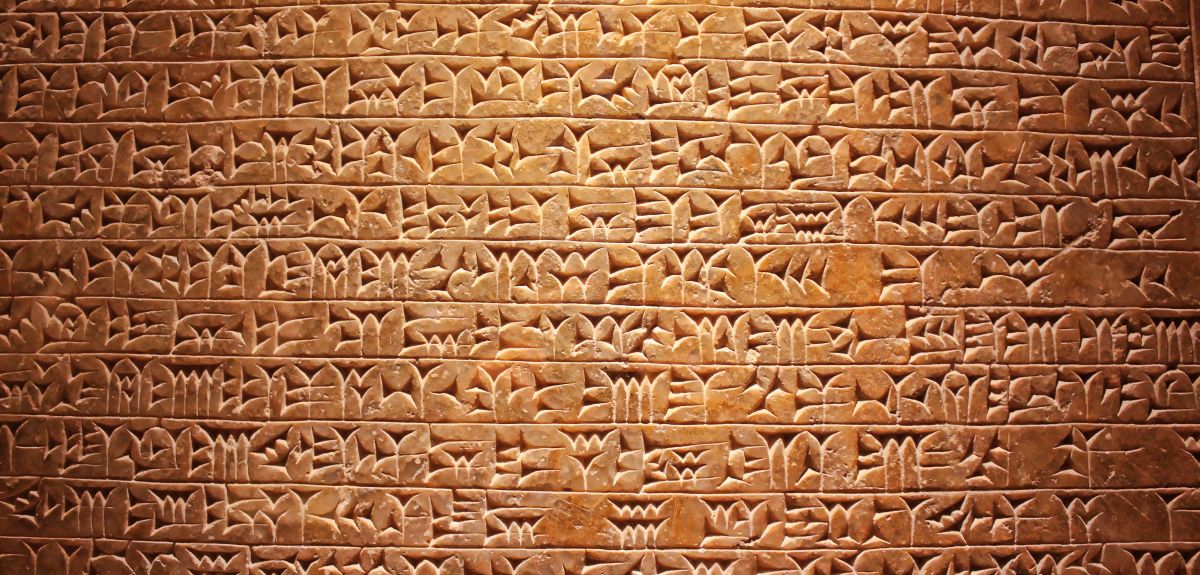

Chronicling 'half of human history', cuneiform texts provide a rich source of information on the rise and fall of ancient civilisations and the daily lives of people of the past.

And with more than half a million original and unique artefacts in museums worldwide, cuneiform texts from ancient Iraq, Iran and Syria – dating from around 3500 BC to the year 0 – represent a resource richer than any other recovered from the ancient world.

The cuneiform system itself is characterised by wedge-shaped signs on clay tablets, representing words or syllables in long-forgotten languages such as Akkadian and Sumerian.

Working with colleagues around the world, Oxford's Professor Jacob Dahl has been co-leading a project to digitise and disseminate many of these important cuneiform texts. Most recently he has spearheaded a collaboration to include the cuneiform text artefacts in the National Museum of Iran (NMI) in the growing online corpus of cuneiform texts.

Professor Dahl, a member of Oxford's Faculty of Oriental Studies and a fellow of Wolfson College, said: 'Cuneiform texts cover half of human history, and the sources from ancient Iraq, Iran and Syria are richer than those of any other ancient civilisation. They cover all topics and genres and include thousands of private letters, lexical texts, literary compositions and above all administrative texts.

'The NMI collection is particularly important for the early period, when cuneiform writing was invented in Iraq and spread into Iran, where a related writing system called Proto-Elamite was developed. The sources for this still-undeciphered writing system are split between the Louvre in Paris and the NMI.

'The Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, which I co-lead, has digitised much of the Louvre collection of cuneiform already, and bringing in the NMI therefore draws together two parts of the same ancient collection. The NMI also holds significant collections of clay tablets, bricks and stones featuring texts from other periods and in other languages – in particular Elamite and Old Persian – which are of interest to specialists well beyond the narrow field of Assyriology.'

Jacob Dahl scans Proto-Elamite tablets in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran.

Jacob Dahl scans Proto-Elamite tablets in the National Museum of Iran, Tehran.The digitisation project was proposed two years ago by Professor Dahl and Jebrael Nokande, Director of the NMI. The first group of Proto-Elamite tablets was scanned and digitised in January and May this year.

Professor Dahl said: 'Since beginning my work on Proto-Elamite tablets almost two decades ago I have waited for an opportunity to work on the texts in the NMI. I spent a lot of effort digitising cuneiform collections in Syria prior to the current unrest, which highlighted for me the need to secure all collections both here and abroad through digitisation and web dissemination.

'The field in general is in the middle of a digital transformation, and it is hard to overestimate the impact of making this collection openly accessible through the internet. Scholars will be able for the first time virtually to reassemble the ancient textual record recovered during the excavations of Susa (modern-day Shush in Iran). It will also open, I hope, avenues for collaboration and sharing of scholarly knowledge between researchers from Iran and the UK concerning a variety of topics, expanding beyond my own subject of Assyriology.'

Professor David Macdonald and Dr Merryl Gelling of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) discuss recent work which questions the efficacy of the mitigation technique and looks at ways to better protect one of Britain’s most endangered wild mammals, the water vole.

The water vole, forever immortalised as ‘Ratty’ in Kenneth Grahams’ classic tale Wind in the Willows, was formerly a common sight on waterways throughout mainland Britain. However, catastrophic declines due to invasive American mink combined with habitat loss and fragmentation have resulted in the water vole now being considered one of Britain’s most endangered wild mammals. As such, water voles and their burrows are fully protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act. Despite these measures, development works affecting the bankside have created an additional pressure on remaining populations and while we might hope Toad is safe in Toad Hall, Ratty has been in peril. However, our research, conducted in collaboration with Natural England, Mammal Society and PTES, amongst others, offers a simple, practical solution.

Natural England created a licence to permit intentional disturbance of water voles - with the idea of giving the voles a chance to move to safety before development work begins. This involved encouraging the voles to relocate by removing any riverside vegetation, and then, once they were thought to be safely out of harm’s way, strategically destroying their burrows to prevent the animals’ return. Such activities, which are intended to conserve the water voles while enabling approved development, are licensed between mid-February and mid-April and must not exceed 50m of bankside length.

However, while the goal of the approach is to displace the animals, our research found that the voles had other ideas. Radio-tracking water voles subjected to this procedure found that they often steadfastly stayed put.

These findings, published today in Conservation Evidence, revealed no overall movement of water voles out of areas where displacement works had occurred. On the contrary, many voles remained faithful to their burrows. The guidelines had always insisted that destruction of burrows should be undertaken cautiously and only during spring, in the hope of saving the lives of any water voles remaining. However, that was in the expectation that at most, only a few bankside denizens would stubbornly refuse to shift. Now it seems the majority stand firm, shifting the balance of risks. This behaviour does not alter between spring and autumn, when vole populations are at their highest.

While labour intensive, the solution proposed in our study - which includes careful excavation of burrows left exposed by vegetation, and then removing the water voles by hand, is worth the effort. With this vole-sensitive and life-saving approach, we believe the displacement method can be a pragmatic and proportional solution for small-scale developments where water voles are present.

Water voles often remained in their burrows after vegetation removal, highlighting the need for burrow excavation to proceed with caution to allow animals to relocate prior to development works starting. There was no difference in behaviour in either spring or autumn, suggesting that works under this licence could occur outside of the current mid-February to mid-April window, potentially reducing costly delays for development works.

It's a particular pleasure to have been able to work with the government’s statutory agency, Natural England, to solve this practical problem, along with leading wildlife charities – a splendid example of all pulling together, and now we hope and expect developers will follow suit.

Not to exhaust the Wind in the Willows reference, but, Toad is in a mess too. However, that’s another story, and one we are busily researching.

The research was carried out in the Upper Thames region and predominantly funded by a partnership between Natural England, Peoples’ Trust for Endangered Species, The Mammal Society, Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, and Thames Water, with additional support from M&H Ecology Ltd, RSK Ltd, Arcadis, ERM Ltd, Ecosulis and the Environment Agency.

How, through the simple, everyday act of drinking a cup of tea, can we explore links to the history of empire, trade and transatlantic slavery? A new Oxford-based project aims to address this question.

Myfanwy Lloyd is a part-time tutor at Oxford's Department of Continuing Education who otherwise works as a freelance historian and museum consultant. Angeli Vaid specialises in heritage and community outreach projects. Along with two Oxford history DPhil students, Elisabeth Grass and Mimi Goodall, they are working with a host of local partners on a project inspired by the Ashmolean Museum's collection of 18th-century porcelain.

What could be discovered from putting these objects into their proper social context? How far have our tea habits in Britain been driven by the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism? From the tea itself, imported via Britain's colonial trade links, to the porcelain and ceramics imported from China, to sugar, the result of exploitation and slavery.

A Wood's Ware 'Beryl' style teacup and saucer, 1940s/50s.

A Wood's Ware 'Beryl' style teacup and saucer, 1940s/50s.Image credit: Fran Monks

The aim of the 'A Nice Cup of Tea' project is to work with local community members to explore the complex legacy of empire, transatlantic slavery and trade, particularly in relation to Oxford city and Oxford University. There are five interwoven strands to the programme:

• Tea Party: a community tea party involving a pop-up exhibition, readings and discussions

• Tea Chest: producing a 'handling collection' of historical and contemporary artefacts to stimulate discussion and creative work in schools

• Tea Shop: a community-led and curated temporary exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum

• Tea Table: a forum to debate the legacy of slave trade and empire with events at the Pitt Rivers Museum

• Tea Tales: creative and artistic performances by young people and community groups exploring the theme

As part of the project's wide-ranging and varied events calendar, A Nice Cup of Tea is linking in to Oxford's History Faculty's annual 'teach-in' on the theme of 'commemorating the Windrush experience'. This year's teach-in is designed to bring alive the experience and impact of the Windrush generation and its descendants. This event will split into four sessions, focusing on 'Windrush and calypso', 'Windrush and literature', 'post-war Asian migration' and 'Oxford's Windrush generation'.

One of the first events is on Sunday 1 July, when A Nice Cup of Tea will be running a community tea party as part of the Oxford Festival of the Arts' 'Around the World in Eight Nations' day, including a pop-up exhibition based on research by Mimi Goodall and Elisabeth Grass. Interspersed throughout the tea party will be poetry and song.

These events are part of a larger suite of commemorative events being coordinated by the African Caribbean Kultural Heritage Initiative, Oxford City Council, the Pitt Rivers Museum, and Oxford's History Faculty.

Prof Paul Newton, Head of the Medicine Quality Group at the Infectious Diseases Data Observatory (IDDO), explains the need for new strategies for tackling poor quality medical products.

The proliferation of poor quality medical products (medicines, vaccines and devices) is an important but neglected public health problem, threatening millions of people all over the world, both in developing and wealthy countries. A recent report from the World Health Organization found that an estimated 1 in 10 medicines in low- and middle-income countries were falsified or substandard. Falsified diazepam found across Scotland has been reported as being “cheaper than chips”.

Falsified and substandard medicines, which may have the incorrect or wrong dose of pharmaceutical ingredients, or no active ingredients at all, may result in death, prolonged illness, side effects or loss of trust in healthcare systems; for antimicrobials they are also likely to be a key driver of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Our ability to tackle the issue is hampered by its complexity. Criminals are becoming more sophisticated, using the internet as well as offline pharmacies for distribution, creating falsified medicines and working across geographical boundaries and in countries with varying legislation and levels of enforcement. Errors in factories without sufficient quality control results in substandard medicines, often containing insufficient ingredients, that because they look genuine are hard to detect.

The issue affects a broad range of stakeholders from individual patients, pharmacists and medicine regulatory authorities to the pharmaceutical industry and law enforcement agencies. We need to better understand the scale of the problem, raise awareness and encourage interventions and support so that every country has a functional medicine regulatory agency to ensure that we all have access to medicines we can trust.

This year we are holding a pioneering conference to bring leading professionals from all over the world to Oxford to discuss strategies for tackling poor quality medical products on a global scale.

The conference will be an important opportunity for the diverse stakeholders involved in medicine quality and regulation to come together within the framework of a dedicated academic conference to share ideas and expertise. One of the event’s key objectives is to develop a consensus statement to be widely disseminated to interested parties and policy makers, forming the basis of a coordinated global effort to tackle poor quality medical products.

The Medicine Quality & Public Health Conference (#MQPH2018) will provide a unique opportunity for medicines regulatory authorities, health workers, scientists, pharmacists, sociologists, economists and international organisations to discuss the problem and outline the necessary steps to address this important issue.

The Conference is expected to attract leading authorities from all over the world, including representatives from a diversity of organisations in low and middle income countries, where the issue of poor quality medicines is often more pronounced due to inadequate surveillance systems.

The Medicine Quality & Public Health Conference will take place at Keble College, Oxford from 23-28 September 2018. More information about the speakers can be found on the conference website.

The deadline for submitting abstracts is 1 June 2018. The deadline for registration is 31 August 2018. A limited number of early bird places are available on a first come, first served basis.

- ‹ previous

- 72 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria