Features

A walking molecule, so small that it cannot be observed directly with a microscope, has been recorded taking its first nanometre-sized steps.

It's the first time that anyone has shown in real time that such a tiny object – termed a 'small molecule walker' – has taken a series of steps. The breakthrough, made by Oxford University chemists, is a significant milestone on the long road towards developing 'nanorobots'.

'In the future we can imagine tiny machines that could fetch and carry cargo the size of individual molecules, which can be used as building blocks of more complicated molecular machines; imagine tiny tweezers operating inside cells,' said Dr Gokce Su Pulcu of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry. 'The ultimate goal is to use molecular walkers to form nanotransport networks,' she says.

However, before nanorobots can run they first have to walk. As Su explains, proving this is no easy task.

For years now researchers have shown that moving machines and walkers can be built out of DNA. But, relatively speaking, DNA is much larger than small molecule walkers and DNA machines only work in water.

The big problem is that microscopes can only detect moving objects down to the level of 10–20 nanometres. This means that small molecule walkers, whose strides are 1 nanometre long, can only be detected after taking around 10 or 15 steps. It would therefore be impossible to tell with a microscope whether a walker had 'jumped' or 'floated' to a new location rather than taken all the intermediate steps.

As they report in this week's Nature Nanotechnology, Su and her colleagues at Oxford's Bayley Group took a new approach to detecting a walker's every step in real time. Their solution? To build a walker from an arsenic-containing molecule and detect its motion on a track built inside a nanopore.

Nanopores are already the foundation of pioneering DNA sequencing technology developed by the Bayley Group and spinout company Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Here, tiny protein pores detect molecules passing through them. Each base disrupts an electric current passed through the nanopore by a different amount so that the DNA base 'letters' (A, C, G or T) can be read.

In this new research, they used a nanopore containing a track formed of five 'footholds' to detect how a walker was moving across it.

'We can't 'see' the walker moving, but by mapping changes in the ionic current flowing through the pore as the molecule moves from foothold to foothold we are able to chart how it is stepping from one to the other and back again,' Su explains.

To ensure that the walker doesn't float away, they designed it to have 'feet' that stick to the track by making and breaking chemical bonds. Su says: 'It's a bit like stepping on a carpet with glue under your shoes: with each step the walker's foot sticks and then unsticks so that it can move to the next foothold.' This approach could make it possible to design a machine that can walk on a variety of surfaces.

It's quite an achievement for such a tiny machine but, as Su is the first to admit, there are many more challenges to be overcome before programmable nanorobots are a reality.

'At the moment we don’t have much control over which direction the walker moves in; it moves pretty randomly,' Su tells me. 'The protein track is a bit like a mountain slope; there's a direction that's easier to walk in so walkers will tend to go this way. We hope to be able to harness this preference to build tracks that direct a walker where we want it to go.'

The next challenge after that will be for a walker to make itself useful by, for instance, carrying a cargo: there’s already space for it to carry a molecule on its 'head' that it could then take to a desired location to accomplish a task.

Su comments: 'We should be able to engineer a surface where we can control the movement of these walkers and observe them under a microscope through the way they interact with a very thin fluorescent layer. This would make it possible to design chips with different stations with walkers ferrying cargo between these stations; so the beginnings of a nanotransport system.'

These are the first tentative baby steps of a new technology, but they promise that there could be much bigger strides to come.

A major exhibition on the 18th century poet and artist William Blake opens at the Ashmolean Museum today, featuring his illuminated books and manuscripts as well as a recreation of his studio.

Blake had little formal education and was isolated from the literary circles of his day. But today he is regarded as one of the major poets of his time: the famous opening line 'Tyger, Tyger, burning bright' is known to schoolchildren across the English-speaking world. Arts Blog explores how his reputation changed.

'Certainly, Blake was better known in his own time as an engraver. That was how he made his living,' said Professor Nicholas Halmi of the English Faculty at Oxford University. 'He wasn't regarded as a 'canonical' poet until after the Second World War.'

Blake was born in 1757 and apprenticed at 15 to a commercial engraver. 'He produced engravings of antiquarian objects - Greek urns and other artefacts - before going to work for a publisher,' said Professor Halmi. 'His poetry was known to a few people, including Wordsworth and Coleridge, although in fact Wordsworth thought he was mad.'

Blake's political and religious views were radical, in some respects even by 21st century standards, and these may have barred him from mainstream popularity, particularly at a time when Britain and France were still at war. 'Blake had a sense of a poet as a visionary or prophetic figure,' said Professor Halmi. 'Someone who had insight into society from the outside, and insight into the spiritual nature of man.

'He was strongly opposed to slavery and 'mental tyranny' - which for him included organised religion. He considered himself a Christian, and Christian themes are apparent in his works, but he hated what he referred to as the 'mind-forged manacles' of the Church. He believed they were not grounded in truth, and in fact kept people from perceiving the truth as he understood it, whereby a spark of divinity was present in all of humanity.'

Blake's unorthodox methods of publication present a more practical reason for the relative obscurity of his work. Although he did publish one conventionally printed book of poems, he moved on to produce small engraved editions of poetry. Approximately ten copies of each work would be printed, then coloured in watercolours by Blake's wife, Catherine. Blake then tried to sell these individually.

'Blake devised a kind of personal mythological system in these works,' said Professor Halmi. 'He drew on Norse and Biblical figures as well as his own private symbolic figures.'

Blake is still an anomalous figure among the "Big Six" male romantic poets, with Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Keats making up the remaining five. 'Blake had no formal schooling, nor was he immersed in the classical literary tradition, although he knew the Bible and English poetry very well,' said Professor Halmi. 'He had to work for a living, he had limited contact with literary circles, and he was not publishing his work conventionally.

'What is also unusual is his level of collaboration with his wife. We often think of the poet as a solitary genius, but printing is collaborative work. Blake had very forward-thinking views about men and women, and he and Catherine were together until death. When Blake was on his deathbed, it's said his last wish was to make a drawing of her.'

Blake's work remained a minority interest through the 19th century, but began to attract more attention into the 20th. Professor Halmi said: 'Later critics have either made use of, or resisted, the idea that Blake is a very obscure poet who has to be decoded or interpreted.

'Northrop Frye, a Canadian critic who tried to demystify Blake, believed that the work can be read as a coherent whole, with the engraved works at its centre. His study Fearful Symmetry, published in 1947, was largely responsible for bringing Blake into the canon. He said quite explicitly that we should think not of Blake as mad, but of the times we live in as mad. For Frye, Blake could offer some sanity to the post-war world.'

William Blake: Apprentice and Master opens on Thursday 4th December 2014 and runs until Sunday 1st March 2015.

A sweet-smelling chemical marker in the breath of children with type 1 diabetes could enable a handheld device to 'sniff out' the condition before a child becomes seriously ill.

That's according to news from the IOP about research reported in their Journal of Breath Research that was co-authored by Professor Gus Hancock of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry.

Professor Hancock is currently working with Oxford spin-out firm Oxford Medical Diagnostics to develop a prototype device, so I asked him about how this technology was progressing and how such a device might eventually be used…

OxSciBlog: Why is diagnosing type 1 diabetes early so important?

Gus Hancock: Untreated type 1 diabetes will result in the build-up of chemicals called ketones in the blood stream to levels which are well above normal values, and this can lead to a serious condition called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), when the blood becomes too acidic. This condition is the main cause of death in children with diabetes and can cause long-term problems. However, diabetes is fortunately quite straightforward to treat if caught early before ketoacidosis occurs and the child is well.

OSB: What link did you find between acetone in the breath and blood ketones?

GH: In this study we tested 113 children and young adults with type 1 diabetes for breath gases and blood constituents. The patients were all attending a regular clinic in the Oxford Children’s Hospital, and they all had their diabetes well controlled with insulin therapy.

We measured the concentration of a specific blood ketone which is used to determine the onset of DKA, and found that the values (which were all well below DKA levels) showed a strong correlation with the concentration of acetone on the breath - the higher values of the ketone were associated with higher levels of acetone. Chemically this is not a surprise it just needed to be proven in this cohort of patients.

OSB: What challenges are involved in developing a handheld device that can diagnose new diabetes from a child's breath?

GH: Let's answer two questions here. First, there are now no scientific challenges to be overcome to build a handheld device to measure acetone in breath of children or adults. The work at the Oxford Children's Hospital used a detection method called reactive ion mass spectrometry, which essentially identifies the molecules in breath by weighing them – not straightforward when there are up to 1000 detectable chemicals in breath. The instrument is the size of a washing machine and costs a quarter of a million pounds.

Our spin-out company, Oxford Medical Diagnostics, out at Begbroke Science Park, has now developed an optical technique to home in to the detection of the single most important diagnostic molecule, acetone. The technique is specific to acetone (ie it's not interfered with by the other 999 constituents) and is sensitive enough for medical needs. The prototype that we have built is the size of a shoe box, and professional designers have now reduced that to a hand held version which is shortly going into production. A single breath is processed presently in a couple of minutes, and that will decrease as we improve the engineering.

So, what would this be used for? People with type I diabetes are encouraged to test for ketones when they are not feeling well or have high blood glucose levels. This is because more insulin is needed if a child is ill, and if the insulin given is not enough, then ketones start to develop. This testing of ketone levels has to be done on a finger-prick blood test. We believe that a simple non-invasive breath test will be more acceptable (no blood required), and will be cost effective.

First, we have to prove that blood ketones and breath acetone track each other as DKA develops. We expect this: we have determined such tracking in non-diabetes volunteers when we induce mild ketoacidosis simply through diet and exercise. We envisage that the instrument will be used at home and could advise the patient whether or not ketone levels are increasing, so a decision can be made as to what should be done and whether or not hospital attendance is necessary.

Will it be used for diagnosis of new diabetes? Here we can certainly say that, if as expected, we find the tracking of blood ketones and breath acetone, it could act as a screening tool: high acetone levels will indicate that further tests are necessary. It will not immediately replace the gold standard of blood testing, but these are very early days, and we need clinical acceptance before we can make a sweeping statement about diagnosis.

OSB: What further research is needed in this area?

GH: We need more clinical data on people of all ages with type 1 diabetes, and are planning this in collaboration with the Oxford Hospitals Trust. We plan to give the handheld device to individuals so they can do frequent breath tests at home, particularly if they are feeling unwell, and we will also test patients who are admitted to hospital with DKA. For clinical use the device will need to pass a number of regulatory hurdles. And of course we are working on the handheld detection of other molecules which may be of importance in disease detection and management.

Cancer requires a blood supply to deliver the nutrients and oxygen it needs to grow and survive. It had been thought that tumours create the blood supply they need by stimulating the formation of new blood vessels, a process called angiogenesis.

But this no longer appears to be the only process going on. Some tumours seem to acquire their blood supply by taking over existing blood vessels, co-opting them for their cancerous growth.

Oxford Science Blog caught up with histopathologist Professor Francesco Pezella of the Radcliffe Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford, who has been establishing the role of blood vessel co-option in lung cancer. His group is now seeking to understand the process and says it could offer new avenues for cancer drug development, and has recently published a commentary on the topic in the Journal of Pathology.

Oxford Science Blog: What is angiogenesis and why is it important in cancer growth?

Francesco Pezzella: The term angiogenesis was first recorded in 1787 and describes the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones. In 1971 Judah Folkman introduced the hypothesis that tumour growth is strictly dependent on this phenomenon because, in his own words, 'Once a tumour take has occurred, every increase in tumour cell population must be preceded by an increase in new capillaries converging on the tumour'. Eventually 'inducing angiogenesis' became considered as one of the hallmarks of cancer, as it was assumed that all the tumours could only grow if they were able to induce formation of new blood vessels.

OSB: New cancer drugs have targeted the growth of new blood vessels. How have they fared?

FP: Not well! In the mid-1990s there were high hopes that these drugs would have produced a quantum leap in the treatment of all the types of tumours. The idea was that by inhibiting the formation of new vessels, all tumours would simply die or, at least, enter a quiescent state. The high expectations of the time are shown in an interview James Watson gave in 1998, when he declared that 'Judah (Folkman) is going to cure cancer in two years'.

While some benefits have indeed been observed, these have occurred only in a subset of cancers and have been modest. More worryingly, both in some animal models and human trials, progression of tumours during anti-angiogenic treatment has sometimes led to a poorer outcome being observed.

OSB: What has your research shown instead?

FP: We were as enthusiastic about angiogenesis as everybody else. However, as soon as we entered the field in 1996, our group discovered that a type of lung cancer called non small cell lung carcinoma could grow in humans without inducing any angiogenesis, and that this was also the case in advanced metastatic disease.

Our observations were in complete contrast to the accepted wisdom of the time: tumours behaving like this were just not supposed to exist.

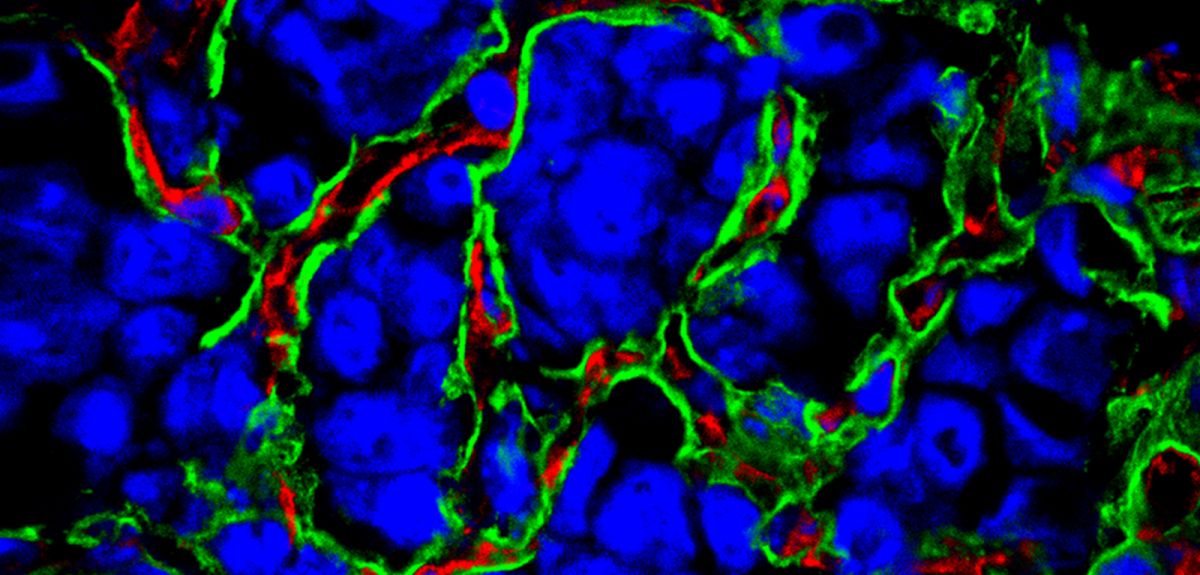

The tumours we identified still have a blood supply, but this is obtained by exploiting, or co-opting, pre-existing blood vessels. These tumours therefore have an underlying biology which is different from that of angiogenic malignancies.

It had been accepted as a general rule that, as a tumour outgrows its blood supply, it starts to receive less oxygen and therefore pathways leading to the formation of new vessels are activated.

Instead, the tumours we described – despite having lower levels of oxygen – are not inducing any new blood vessel formation. They are responding to the diminished availability of oxygen in a different way that we still do not fully understand, but it is potentially linked to a re-programming of the way in which the cancer cells produce energy.

Camera lucida drawing from 1861 showing cancer cells growing inside lung alveolar spaces

Camera lucida drawing from 1861 showing cancer cells growing inside lung alveolar spacesHowever these histopathological observations have been widely ignored in favour of data from animal models, which had pointed to an absolutely essential role for angiogenesis in cancer.

OSB: Do different types of cancers, or at different stages, maintain their blood vessel supply in different ways?

FP: Yes, a primary angiogenic tumour can relapse years later as a non-angiogenic tumour, and vice versa. Even within the same tumour there can be areas attracting new vessels and areas exploiting pre-existing ones. This is actually a rather common scenario.

OSB: What are the next steps in your research/what are the open questions we now should explore?

FP: There are now two main key questions to be answered:

1) Why in some cancers is there no angiogenesis, and how can a tumour switch from angiogenic to non-angiogenic status and vice versa? Recently animal models for non-angiogenic growth have become available and they are allowing us to start to tackle the problem by mapping the pathways involved. Once we have a clearer idea of the pathways involved, we can identify the molecular mechanisms at work by trying to switch the cells from one status to another.

2) How do cancer cells co-opt blood vessels? Only a few studies have so far addressed this issue, but already we know that is a promising field because, by understanding which proteins are mediating this process, we can think about disrupting vascular co-option with drugs. This approach could deliver some useful treatments. Furthermore there are clues suggesting that the blood vessels co-opted by the tumour start to express proteins which they normally would not produce, making them different from other, normal blood vessels and therefore a possible target for treatment.

OSB: What does this all mean for new cancer treatments?

FP: Our observations explain some of the poor results observed with drugs directed only against angiogenesis. But while we have put aside forever the idea of a magic bullet able to kill all new blood vessels and cure cancer, we have also unveiled potential targets for new treatments.

We can now aim to target the pathways responsible for the metabolic re-programming of cancer cells, and any other pathways yet to be identified as responsible for the non-angiogenic behaviour. We would move from not bombing just the roads and the railways, but the factories too!

The discovery that cancer cells can survive by co-opting vessels opens an opportunity to test compounds and therapeutic antibodies able to block the co-option, and a few first candidates to target with drugs are already emerging.

Although we cannot be as optimistic as James Watson was in 1998, we think that the more complete picture we are getting of the interaction between cancer cells and blood vessels is likely to deliver some improvement in treatment in the future by targeting both angiogenesis and taking over of existing vessels.

Renowned tenor Ian Bostridge was in Oxford last week as the Humanitas Visiting Professor of Classical Music and Music Education.

To an audience of students, academics and interested members of the public, he gave a lecture entitled "Why Winterreise? Schubert's Song Cycle, Then and Now" and led a masterclass/open rehearsal and an all-day symposium.

In his lecture, Mr Bostridge discussed the meaning of a liberal education. He stressed the importance of both the arts and sciences and warned against judging the value of each by 'the methods of accountancy and the business school'. He told the audience: 'One of the main ways through which this ideal of liberal education works, in its vision of unconstrained but disciplined intellectual exchange, is through what one might call the circulation of metaphor, so that the most unlikely of disciplines can offer inspiration to each other. Sciences inspire the arts, the arts the sciences.

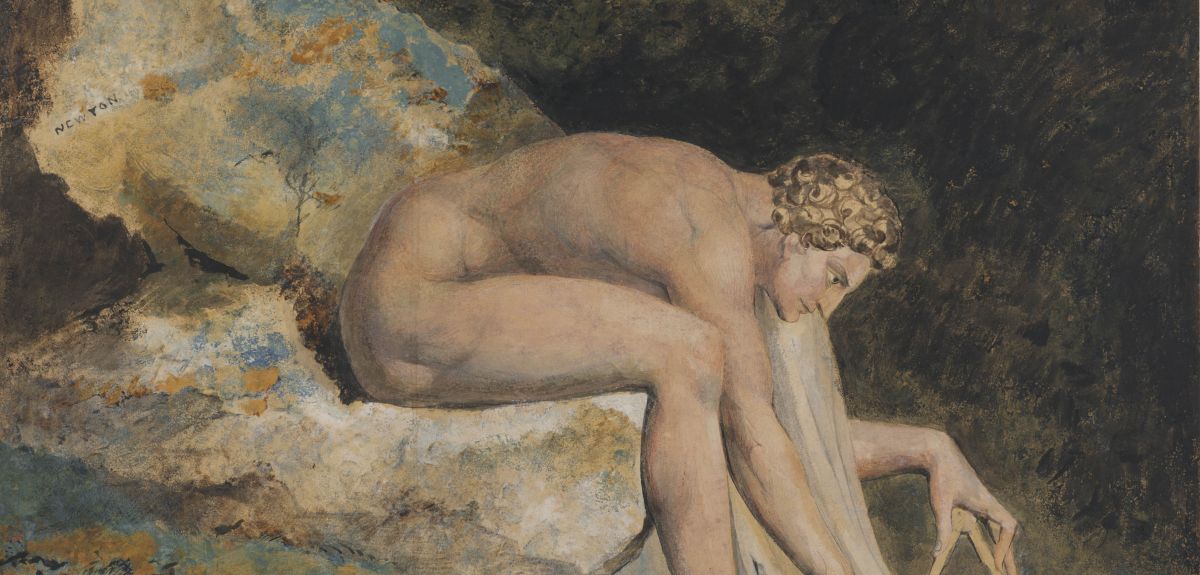

'My favourite historical example involves music. Musical metaphor has played a crucial role as midwife in the physical sciences from the time of Pythagoras. Musical theory was a crucial, if publicly underplayed, component in Isaac Newton’s understanding of light – through an analogy between the colour spectrum and the musical scale. The seven notes of the scale before the return to the octave are analogous to the colours of the rainbow – red, orange, yellow, green, blue and violet, plus the strangely superfluous indigo which made the number up to seven.

'More significantly, Newton interpreted Pythagoras’s views on musical consonance as containing the essence of the inverse square law of gravitation, his dazzling solution to the unity of celestial and terrestrial dynamics. Thus Newton, a sort of Pythagorean magus, reinterpreted the notion of the harmony of the spheres.'

A longer extract of this lecture can be found here.

Mr Bostridge has had a distinguished international recital career. His operatic recordings have won major international record prizes and been nominated for 13 Grammys. He was previously a fellow in history at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and has received honorary fellowships from Corpus Christi College and St John’s College. He was made a CBE in the 2004 New Year's Honours.

This professorship was been made possible by the generous support of Mick Davis and was being hosted by Professor Jason Stanyek in association with St John's College. Humanitas is a series of Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intended to bring leading practitioners and scholars to both universities to address major themes in the arts, social sciences and humanities. Created by Lord Weidenfeld, the programme is managed and funded by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue with the support of a series of generous benefactors and administered by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

- ‹ previous

- 158 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria