Features

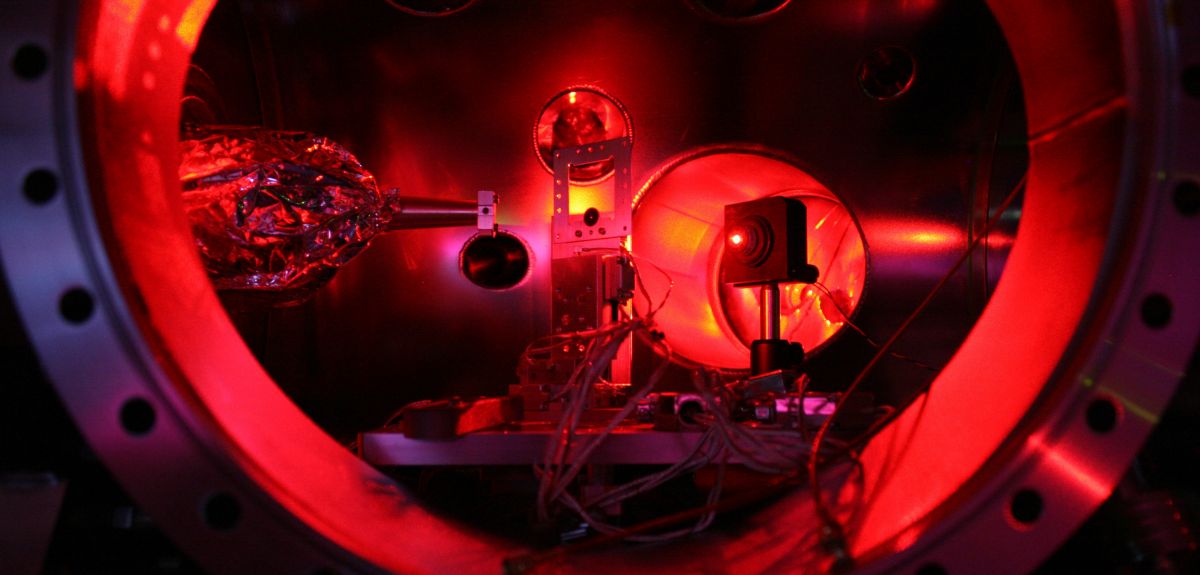

By recreating the extreme conditions similar to those found half-way into the Sun in a thin metal foil, Oxford University researchers have captured crucial information about how electrons and ions interact in a unique state of matter: hot, dense plasma. Their snapshot of the fraction of a trillionth of a second during which these extreme conditions existed during the experiment found that previous theoretical models used to inform how quickly atoms ionize and heat up in a dense plasma were off by a factor of three.

I caught up with Dr Sam Vinko, the lead researcher of the study published in Nature Communications, and I talked to him about how to recreate stellar conditions in a lab in California.

OxfordSciBlog: Your study investigates conditions during a plasma; what is this state, and why is it important to look at it?

Sam Vinko: A plasma is a collection of electrically charged particles: a flame is a common example, but plasmas are ubiquitous – they are the most common state of matter in the visible Universe. For example, our Sun in made of plasma, a soup of electrons and ions at high temperatures and densities.

Using intense X-rays, we've been looking at how to recreate extreme states of matter, conditions similar to those found half-way towards the centre of the Sun, in a lab. We managed to create a plasma at a density typical of a solid, but heated to several million degrees centigrade.

We're interested in these sort of extreme states of matter for many reasons; they are important to understand how matter behaves in the cores of large planets, various types of stars and other astrophysical phenomena, in intense laser-matter interactions, and also for inertial confinement fusion (ICF) research.

Inertial confinement fusion is a process where hydrogen isotopes are merged together to create helium, a neutron and quite a bit of energy, in a way similar to what happens in the core of stars. It's a potentially very promising source of energy for the future, but we still need a better understanding of the physics of matter in extreme conditions to get it to work controllably in a lab.

OSB: How did you create this hot, dense plasma?

SV: We created this plasma state by exposing a very thin sheet of aluminium foil to X-ray laser pulses produced by the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in Stanford, California. This is the most powerful X-ray source every made, and the X-rays are focused on a spot 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair. The end result is of course a hole in the foil, as the ions quickly heat up and the foil explodes.

But atoms and ions have some, albeit small, mass. Because of this mass, they have some inertia. And this inertia means that it takes some amount of time for the ions to move and for the material to actually explode. The trick here is that if you can do all your physics before this explosion happens, you’ve got what is called 'inertial confinement': the plasma is being held together by the inertia of its constituent atoms and ions.

So we created a hot and dense plasma by taking advantage of this inertial confinement: we dumped a large amount of energy very, very quickly onto a solid target, in the fraction of the trillionth of a second, before the material has had a chance to explode. This is the point where we take all our measurements: before the material blows up.

OSB: How long did you experiment last then?

SV: Our entire experiment is over in about 50 femtoseconds (a femtosecond is a quadrillionth of a second). This is an unimaginably short amount of time, but to give you a sense of how short it is: there are more femtoseconds in a single minute than there have been minutes since the beginning of the Universe!

OSB: What do you measure during this short time?

SV: We do spectroscopy: we record and then analyse the light emitted during the experiment to find clues about the underlying processes. One key problem is how to limit this analysis only to the radiation that is emitted in the first 50 femtoseconds of the experiment.

The trick we use to get around this problem takes advantage of the fact that the inner-most electrons orbiting the nucleus remain tightly bound, even in the hot plasma conditions we create. They are only knocked lose by the high-energy X-rays we use. So the 'fingerprints' of these innermost electrons are only visible when the X-ray beam is on, which in turn allows us to observe the sort of extreme conditions you’d find ordinarily only inside stars.

We analysed these spectral 'fingerprints' to track a specific property that we were interested in: collisional ionization.

OSB: What is collisional ionization?

SV: Electrons which have been knocked out of their orbits (e.g., by the high-intensity X-ray pulse that we used) collide with other electrons inside atoms and ions, in turn knocking them out from their orbits: this is known as (electron) collisional ionization.

The rate at which collisional ionization takes place in a material is very dependent on its density: if you have a gas, it's more likely that a free electron will just fly off without bumping into anything else. In a more dense material, it's more likely to bump into another electron.

But the rate at which this collisional ionization happens has never been measured in a dense plasma before, in part because it is so very quick – on average it takes place in less than a femtosecond!

OSB: Why is it important to measure these rates?

SV: Collisional rates are essential to model and understand how a dense plasma (such as that found in an astrophysical object or in an inertial confinement fusion experiment) is created, and how it heats, ionizes and equilibrates.

These collisional ionization rates have previously been either calculated from theory or extrapolated from measurements in very diluted systems, but have never been measured directly in a dense system. We’ve now found a way to measure these rates for a hot, dense plasma.

OSB: What did you find?

SV: Firstly, we've shown that it is possible to measure very, very short-lived events, by tracking them with respect to other short-lived events that have a clear 'fingerprint'. The trick was to use Auger decay (a very fast process where electrons inside an atom or ion are reshuffled to fill a hole in a deep state) as an ultra-fast clock to time a collisional event in a single ion – a process that takes on average less than a million-billionth (quadrillionth) of a second to happen.

By measuring these ultra-fast events, we've found that the collisional rates are actually much higher than had been assumed previously: it’s not a small amount either, since the rates we find are more than three times faster. So the ionization process seems to be a lot more efficient than people had thought previously.

We're hoping that this is the first of many experiments aimed at replacing untested models with quantitative, experimentally measured values. The fact that current models don't quite work in many conditions isn't really a surprise, given their reliance on extrapolations and unverified assumptions. Excitingly, we now have a method that can provide the experimental data to plug in the gaps.

This week, Oxford students will investigate ethical puzzles - from the everyday to the extraordinary - through a practical lens.

The Oxford Uehiro Prize in Practical Ethics has been organised by the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics in Oxford University’s Faculty of Philosophy. The four finalists in the competition will present their cases in an event on Thursday 12 March which is open to the public.

Professor Julian Savulescu, director of the Centre, said: 'This competition aims to bring students from across Oxford together to think about an issue in practical ethics, drawing on their own expertise whether that is philosophy, politics, theology, or even science or medicine.

'Whatever career our students choose, a workforce which is trained to identify ethical problems, think logically about how and why they occur, and find an ethical solution will be a positive step forward for the future.'

The four philosophy students have given Arts Blog a preview of their arguments.

Should I stop playing music in my room because my neighbour can hear it through the wall?

According to Miles Unterreiner, a graduate student at St John's College, we all engage with practical ethics, whether we're aware of it or not.

'Supposing my displeased neighbour wants me to stop listening to music because she can hear it through the wall,' he said.

'I think I have a right to play music in my own room. Should she buy earplugs, or am I obligated to buy headphones?

This is a small and relatively insignificant example, one of the many questions about right and wrong that we ask ourselves every day.

How many lives can you save?

'If we care about the well-being of others, we should try to improve the lives of as many people as possible by as much as possible,’ said Dillon Bowen of Pembroke College, who has researched the most effective ways to give to charity.

'Now, when you first hear this, it seems like a strikingly obvious idea. If I donate £100 to charity, and I have the choice between donating to a charity which can save two children from starvation, or one which can save 20 children, I ought to choose the latter.

'But these sorts of economic questions don't often enter into people's minds when they donate money. People see someone in need, feel a strong visceral desire to help, and donate to the cause. End of moral calculus.

'But when it comes to morality, we need to think more reasonably. It's good that we want to help people, but bad that the way we go about doing it is so ineffective. We need to retain the altruistic intuition to help others, but use our reason to make sure we're helping others effectively.'

How should you live if you care about animals?

Xav Cohen, of Balliol College, is vegan because he cares about the harm that comes to animals from humans eating meat and using animal products. But it's hard to say how vegans should behave if they really want to minimise harm to animals: should they try to convince as many people as possible to adopt a fully vegan lifestyle?

'I found that vegans should really be looking to build a broad and accessible social movement which allows people to reduce their consumption of animal products, rather than condemning anything that isn't full veganism,' he said.

'This will lead to less harm to animals overall. What's needed is a popular label or movement which is plural and accepting, with the only requirement that we do more to reduce harm to animals.'

Should people be allowed to have breast implant surgery if it will harm them?

'Some would argue that a woman’s decision to have breast implants is morally unproblematic, as long as the woman is not coerced into having the surgery,' said Jessica Laimann, also of Balliol College. 'But if women believe that their success, self-worth, and even their careers depend on their appearance, is this still the case? Arguably, breast implant surgery is significantly harmful.'

So should we prohibit this kind of surgery in order to protect people from harming themselves?

'I immediately feel uneasy about the idea of prohibition. There is something deeply problematic about letting a society create people with the desire to inflict harm on themselves, and then trying to solve the problem by prohibiting these people from acting on that desire.

'Prohibiting breast implant surgery would put the lion’s share of the costs of changing harmful social norms on the people who already suffer most from them. Instead, we need to forcefully address the circumstances that make them willing to harm themselves in the first place.'

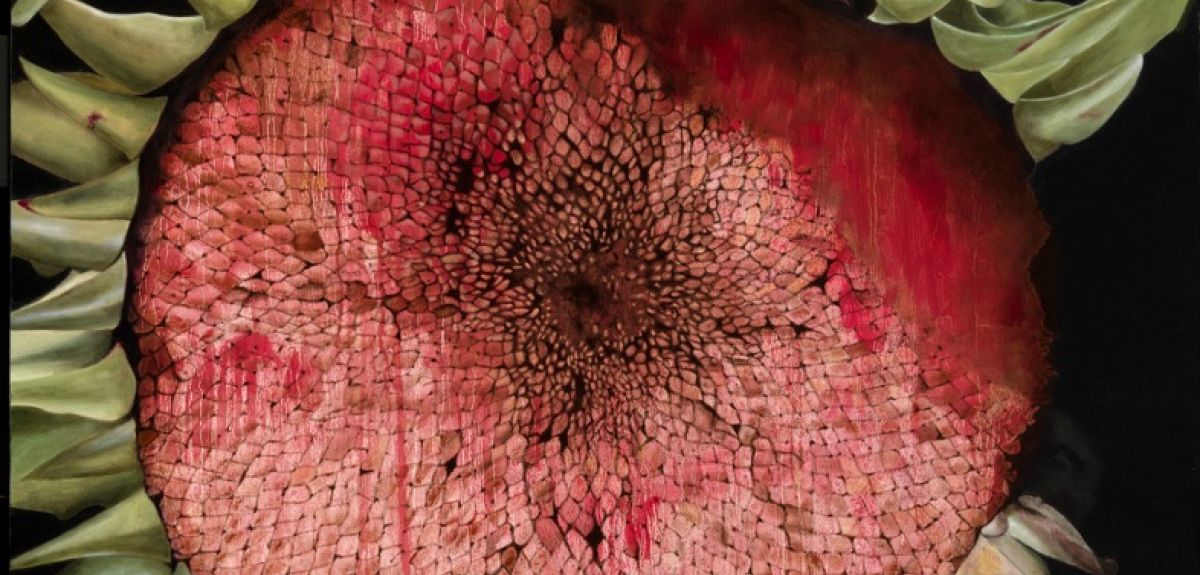

Artist Patrice Moor has spent the last 18 months as artist in residence at the University of Oxford Botanic Garden. 'Nature Morte', an exhibition based on her time at the Garden, opens on Saturday 7 March.

'My subject is not morbid – there is an emphasis towards life holding death in mind and the cycle of life,' says Patrice.

'Gardens lend themselves well to this and I felt hugely privileged to be able to observe and spend time at the Oxford Botanic Garden. Each season is full of interesting changes, as an artist all things can be a source of inspiration.

When Peter Medawar began his research career at Oxford University in 1935, he remarked that he was '(allocated) a room much too good for a beginner'.

This generous gesture from Professor Howard Florey who allocated the room turned out to be far-sighted: while at Oxford, Peter Medawar made the first discoveries that ultimately led to him winning the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1960. His eventual discovery of how the body can learn to accept tissues from another donor opened the door to successful organ transplantation

He was also a well-known science communicator in his day, giving the 1959 BBC Reith lecture and writing numerous books and articles for a general reader. Richard Dawkins has called him 'the wittiest of all science writers.'

2015 marks the centenary of his birth, which has just been celebrated with a special lecture series at the Department of Zoology, where he was an undergraduate.

Beginning research

Peter Medawar completed a first class honours degree in Zoology at Oxford in 1935, after which he was awarded the Christopher Welch scholarship and the senior demy of Magdalen.

But the Zoology department did not have the equipment for the tissue culture work which became the focus of Medawar’s DPhil, so he was dispatched down South Parks road to the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology. The School was the site of a new state of the art lab – and a new Professor of Pathology, Howard Florey.

Howard Florey himself won the 1945 Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine for his role in the making of Penicillin, the new 'wonder drug' whose effects were nothing short of miraculous at the time.

The research team that Florey recruited – including the young Peter Medawar – ushered in the modern age of antibiotics.

While Medawar was mostly working on tissue cultures at this point, he also contributed experimental results to the famous second 'Penicillin paper' which established Penicillin’s effects in a living organism, even though he is not credited as an author.

The hard graft

Medawar continued working in Oxford as the second world war began, dramatically changing the direction of his research.

During the Battle of Britain, the now-married Peter Medawar and his wife heard an aeroplane flying low over their Oxford garden, followed by an almighty crash. Oxford was spared the bombing that affected many other cities, and the sound they heard was not a bomb but the crash landing of a British plane.

The plane pilot was badly burnt, and his doctors asked if Medawar's experience with tissue culture could help in treating him in any way. Medawar was also challenged by a colleague who had a clinical interest in the treatment of severe burns to see if he could grow skin in tissue cultures.

Responding to this challenge, Medawar travelled up to Glasgow (where he later claimed that his diet consisted of 'allotropes of porridge'), and worked on transplanting patches of skin from donors to burn patients.

He found that a second set of transplants was rejected much faster than the first, a finding that highlighted the role of the immune system in the rejection of donor tissue.

Back in Oxford, Medawar continued his work on dissecting how the immune system reacted to tissue grafts from another donor, eventually leading to their rejection.

By the time he left Oxford in 1947, Peter Medawar’s research had already established that the body rejected tissue grafts from a genetically unrelated individual through an immune mechanism, and that this mechanism was not mediated by conventional antibodies.

Medawar continued his research at the University of Birmingham and at University College London, writing the seminal Nature paper which described how to make normally-rejected donor tissue grafts immunologically acceptable to the body.

This discovery paved the way for organ transplants. For his role in this work, Peter Medawar was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1960.

Later life

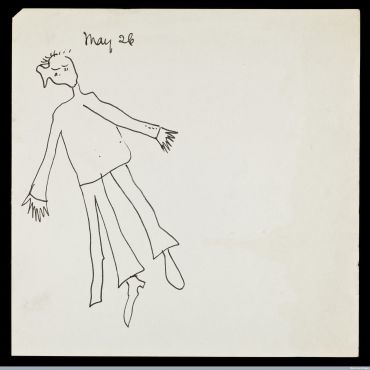

Peter Medawar was struck down by a stroke while delivering a speech in Exeter Cathedral in 1969, but he continued to write through the multiple strokes he suffered until his death in 1987. He made the self-portrait below while recovering in a respite home in 1970.

The Peter Medawar Building for Pathogen Research at Oxford University was named in honour of his contributions to scientific research.

'Peter Medawar was an absolutely brilliant teacher,' according to one of his former students, Dr Henry Bennet-Clark, Emeritus Reader at the Department of Zoology. 'He not only made sure that we knew the facts, but he also provoked our interest in science.'

Dear wife and bairns

Off to France – love to you all

Daddy

On first reading, this note from George Cavan to his wife Jean and three daughters does not appear out of the ordinary.

But it was the last message he ever wrote to his family, two weeks before being killed in action on 13 April 1918 at the Battle of Hazelbrouck in France. The note only reached his family thanks to the goodwill of a passer-by.

George's granddaughter, Maureen Rogers, picks up the story. 'At the end of March 1918 George was away at training camp the orders came through to dispatch to France,' she explains.

'The train he was on with his troops went through his home station (Carluke in Scotland) but did not stop there. He threw out onto the station platform a matchbox containing a note to his family.

'On one side was the name of his wife and on the other the message to the family.'

The note came to light when Maureen submitted it to Oxford University's Great War Archive, which has collected and digitized more than 6,500 items relating to the First World War that were submitted by the general public.

The Archive was set up by Dr Stuart Lee of Oxford’s English Faculty and Academic IT Services and was used as the model for the Europe-wide Europeana 1914-1918 project..

Maureen lives in Australia and the subsequent blog post on the Great War Archive website triggered an unexpected set of events.

'We received a comment from George's family in Scotland who were unaware of the matchbox story,' says Alun Edwards, a project manager of the Great War Archive.

'Through this the family branches were able to join together their elements of their ancestors' stories. This formed the basis for a chapter of a book, published by the British Library, called "Hidden Stories of the First World War" by Jackie Storer.'

IT Services' work at the forefront of community collections will be presented at the forthcoming 19th annual Museums and the Web conference in April 2015 in Chicago.

- ‹ previous

- 153 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria