Features

In the world of fossils it's usually befanged predators or their feathered bird-like cousins that steal the limelight.

So finding out about Bonnericthys, one of the unsung heroes of the Jurassic & Cretaceous - as part of working on this news story - has been an unexpected treat.

These giants were about as far from the flesh-eating inhabitants of Jurassic Park as you can get: 9m-long fish gliding around the prehistoric seas hoovering up plankton much like the benign basking sharks, whale sharks and blue & grey whales we know today.

Big & small fry

Making the video turned up a lot of fascinating detail and context that didn't make the final cut: like the fact that these large filter-feeders shared the ancient oceans with the ancestors of smaller fry living off the same resources, such as early herrings and anchovies.

'These familiar fishes survive to the present day, but the most striking difference between these suspension feeders and the extinct ones we've studied is size,' Matt Friedman, of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences, told me.

'The extinct fishes reaching lengths of 9m or more are giants on any scale, but they are particularly massive in comparison to living bony fishes that thrive on plankton.'

The awkward size and shape of some of the museum specimens is one reason why they were misidentified or ignored, but another factor is the peculiar anatomy of the giant plankton-eater:

'First is the enormous mouth, with long, slender jaws that bear no teeth whatsoever - a feature common to filter feeders,' Matt explained.

'Another important feature is the enormous gill skeleton: Fishes use gills to breathe, but suspension feeders have co-opted their gill arches to extract plankton from the water. They pull off this trick helped by structures called gill rakers, finger-like projections that extend off the front of the gill arches, which can assume elaborate shapes in suspension feeders.'

'As for the body of these animals, it would have been very streamlined, with a well-developed pair of fins just behind the head, and a massive, crescent-moon shaped fin at the back of the tail.'

Things fall apart

These specialised lightweight bodies, fine-tuned by evolution, contain skeletons with very little bone - so that they tend to fall apart after death, leaving only fragments of skull and flipper to sink to the ocean floor and be preserved.

It was a series of new finds from excavations around the world that helped unlock the story of Bonnericthys:

'The most important fossil specimens for our study came from rocks laid down in western Kansas near the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 80 million years ago. We've also got other pieces of this same fish from other parts of the US including New Jersey, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Alabama,' Matt told me.

'Other examples of this group of fishes that we report for the first time came from Kent and Dorset here in the UK, as well as from as far away as Japan.'

These giants proved to be quite the globe-trotters, but it is the longevity of their 100m-year-dynasty that marks them out as an evolutionary success story rather than just an interesting experiment, Matt comments:

'They cruised the oceans for at least 100 million years. To put this in context, that's longer than the giant baleen whales have been around, and longer than any of the groups of massive filter-feeding sharks.'

'Another way to think about these fishes is by comparing them to mammals: mammals have been dominant on land for something like 65 million years, the time from the end of the age of dinosaurs up to today. I think we'd all agree that mammals are a pretty successful group.'

'Of course these giant fishes never achieved the diversity of mammals, but they were in the oceans for a longer period of time than mammals have been the dominant land vertebrates.'

If you've ever been frustrated by wanting to take video and hi-res photos at the same time on your camera, you're not alone.

Physiologists from Oxford University faced just such a problem when they were trying to record what happened to heart tissue cells in their lab. Their homemade solution proved so useful that they are now working with Oxford University Innovation to turn it into a commercially-viable technology.

As Colin Barras reports in New Scientist the two Oxford researcher, Gil Bub and Peter Kohl, rebuilt a standard video camera to incorporate the digital chip from a home cinema projector - a chip that's studded with lots of tiny moving mirrors.

By fixing the chip between the camera lens and its image sensor they used the chip's mirrors as 'shutters' to slice the video into 16 lower-resolution frames: squeezing 400 frames per second out of the camera's standard 25 frames per second set-up.

Even better, as each set of 16 sequential frames come from different pixels on the same sensor, they can be combined to give hi-res images like a stills camera (see the image below).

'What's new about this is that the picture and video are captured at the same time on the same sensor,' Gil told me. 'This is done by allowing the camera's pixels to act as if they were part of tens, or even hundreds of individual cameras taking pictures in rapid succession during a single normal exposure.'

'The trick is that the pattern of pixel exposures keeps the high resolution content of the overall image, which can then be used as-is, to form a regular high-res picture, or be decoded into a high-speed movie.'

The new system, which the team describe in this week's Nature Methods, is likely to cost a fraction of the current price of cameras with this combined capability and could transform everything from CCTV to sports photography.

The project was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the British Heart Foundation.

Heart strings

Heart stringsIf you thought 'tugging at your heartstrings' was just an expression, think again.

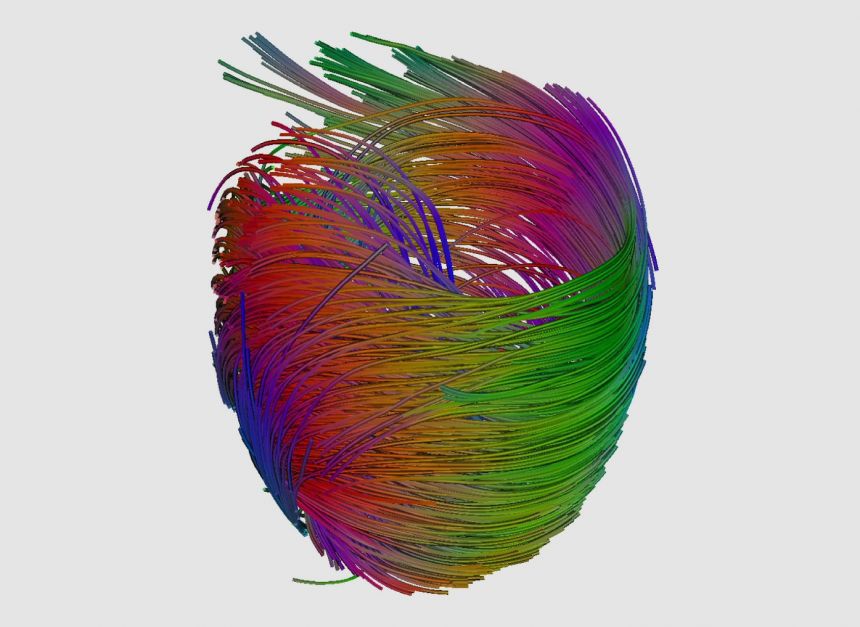

In a tale appropriate to the cardiac-thumping run up to Valentine's Day an Oxford University researcher has produced an image showing the orientation of 'strings', or more scientifically-speaking 'muscle fibres', within the human heart.

The image above by Patrick Hales, from Oxford University's Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics [WTCHG], won the runner up prize in the British Heart Foundation's Reflections of Research competition.

It was generated from an MRI scan of a heart, using Diffusion Tensor Imaging. The scan tracks the movement of water molecules throughout the heart muscle, which reveals how the muscle cells are aligned. The lines represent the orientation of muscle fibres in the heart’s biggest chamber, the left ventricle.

'This technology allows us to model the structure of muscles in the heart in a non-invasive way, and how diseases can cause it to change,' Patrick told us.

'In the future, we hope that our research might be able to determine how the structure of the heart is damaged during a heart attack, and how the muscle fibres respond.'

'We also hope that our computer models of individual hearts will one day be used as a tool for diagnosis, and could even provide patient-specific assessment of treatment options. Imagine your doctor trying out treatments on a ‘virtual’ version of you, before choosing the right prescription.'

The image was produced as part of a collaborative research project between researchers at medical, basic science, and computing departments at Oxford University, funded jointly by the BHF and the BBSRC.

Also deserving a special mention is the image 'The tree of life' (below) by Patrizia Camelliti of Oxford's DPAG that made the competition's shortlist.

It shows the orientation of cells deep within the heart, visualised using multiphoton fluorescence microscopy. The cells have been stained with special pigment molecules which absorb the light from a laser and emit light of a different wavelength.

According to Patrizia: 'The muscle cells of the heart intertwine like the branches of a great banyan tree. This intricate structure is essential for generating force to pump blood around the body.'

'My research aims to reveal the complex structural and functional alterations affecting the heart during heart failure, and how people with this condition can be helped by implanted devices that help the heart to pump.'

'The results will help engineers improve the design of these devices, with direct benefits for the thousands of people awaiting a heart transplant.'

Could the carbon dioxide belched out by heavy industry be put to good use?

It's a question a number of researchers are looking into including Dermot O'Hare and Andrew Ashley of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry.

They have developed a new process for capturing and storing CO2 and converting it into the useful chemical and fuel methanol. A report of their research is published in the journal Angewandte Chemie, and they are now working with Oxford University Innovation to exploit their idea.

Dermot told The Engineer that 'CO2 is a hard nut to crack because its bonds are very strong,' but that 'methanol is quite a nice fundamental building block for organic chemistry.'

He goes on to point out that right now most of the methane we use comes from fossil fuel reserves and that their technique would be win-win in that it would both sequester CO2 and produce a useful chemical and possible alternative fuel source for vehicles, devices or power plants.

The process works by harnessing the power of highly reactive chemical mixtures called Frustrated Lewis Pairs (FLPs).

FLPs are able to rip apart hydrogen molecules and bond with the hydrogen ions. But after this reaction the Oxford team worked out that the Pairs would still be 'frustrated' and reactive enough to bond with CO2. They've now shown that their approach can exclusively produce methanol from CO2 at low temperature and pressure (160 °C at standard pressure).

'Current technology is not selective for methanol and therefore not carbon efficient,' Dermot told us. 'Side products of other carbon capture technologies such as carbon monoxide and methane can also be just as undesirable as CO2.'

As well as not producing these unwanted byproducts the new process doesn’t require expensive and toxic transition metal catalysts and is not poisoned by carbon monoxide - a gas often created during incomplete combustion.

The Oxford team are currently looking to make the process suitable for industry and Isis Innovation has patented the technology and is working with the inventors on a strategy for commercial development.

For more contact Jamie Ferguson: [email protected]

Read more in The Engineer and New Scientist

Today's Times carries a letter from scientists working on the Cassini mission.

Cassini, you may remember, is one of the projects that STFC has chosen to withdraw from as part of a cost-cutting exercise. It's also a project that Oxford scientists have made a major contribution to.

Simon Calcutt, from Oxford University's Department of Physics, is one of the letter's signatories who write: 'the UK Cassini teams that discovered the ice volcanoes on the Saturnian moon Enceladus, the rich chemistry of the prebiotic atmosphere of Titan, and the mechanism of Saturn’s auroras now face imminent disbandment, abandoning still-functioning UK-led instruments in orbit around the planet.'

Unless other funding sources can be found the decision signals a sad end to what has been a major UK science success story. Both Mark Henderson in The Times and Jonathan Amos on BBC Online mull over the consequences and how it might impact on UK involvement in future missions and the next generation of British space scientists.

Whatever you think about how spending on space science should be prioritised it's worth noting just what a phenomenal success Cassini has been so far, even just from the Oxford perspective:

Back in January 2004 Oxford University scientists working on data from Cassini identified a jet stream in Jupiter's atmosphere that resembles similar weather features found on Earth.

They were part of the team behind the Infrared Spectrometer that, in July 2004, was sent to scrutinise Saturn, its rings and moons, as the spacecraft hurtled by the giant planet.

Years of data crunching and modelling saw them make a series of major discoveries, highlights include:

Finding a hexagon-shaped 'hot spot' in the middle of Saturn's chilly north pole: the result of air moving towards the pole, being compressed and heated up as it descends over the poles into the depths of Saturn. Reported in Science, this gave clues to the atmospheric formations found on Jupiter, Neptune and Mars.

New observations of Saturn showed that its southern polar vortex is similar to hurricanes found on Earth. Both have cyclonic circulation, a warm central 'eye' region surrounded by a ring of high clouds - the eye wall - and convective clouds outside the eye. These 'saturnicanes' also resembled polar vortices on Venus, giving further weight to the idea that understanding the weather on one planet call tell us a lot about weather on others (including our own).

Only last year, Oxford scientists using Cassini reported in Nature that they had come up with a new way of detecting how fast large gaseous planets are rotating: a method which suggests Saturn’s day lasts 10 hours, 34 minutes and 13 seconds – over five minutes shorter than previous estimates based on the planet’s magnetic fields.

These are just a few examples and, according to NASA, in Cassini's new extended mission there should be many more exciting discoveries to come:

'The extension presents a unique opportunity to follow seasonal changes of an outer planet system all the way from its winter to its summer... The mission extension also will allow scientists to continue observations of Saturn's rings and the magnetic bubble around the planet known as the magnetosphere. The spacecraft will make repeated dives between Saturn and its rings to obtain in depth knowledge of the gas giant. During these dives, the spacecraft will study the internal structure of Saturn, its magnetic fluctuations and ring mass.'

It's a shame that it looks like researchers from Oxford and around the UK will only be able to cheer the plucky old probe on from the sidelines instead of being at the heart of a truly unique space odyssey.

- ‹ previous

- 220 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria