Features

Yesterday, Britain triggered Article 50 to begin the formal process of leaving the European Union. To mark the occasion, our guest author today is Katrin Kohl, Professor of German Literature at Oxford, who leads a major research project into languages called Creative Multilingualism.

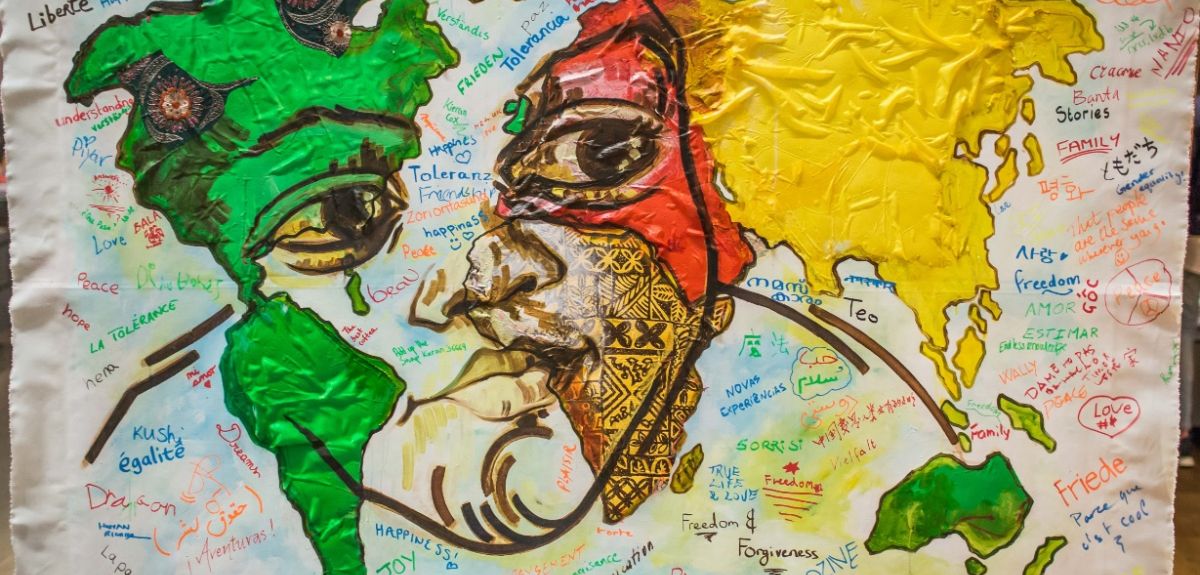

'Creative Multilingualism – Oxford’s biggest ever Humanities research programme – got off the ground on 1st July 2016, a week after the Referendum vote to leave the European Union. The nature of the research, and the funder’s requirement that it should have an impact on UK society, have made it impossible to ignore the interplay between research and politics.

The programme is being funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of their ambitious Open World Research Initiative. At a time when the political emphasis has been on strengthening borders and building walls, the only option for our research team has been to embrace the connection between research and politics as part of multilingualism’s rich tapestry.

Languages are inherently and inexorably connected with the cultures of the people who learn them, care about them, and use them. And culture is never apolitical – as we have seen in recent months, cultural identity matters, and a passion for status can drive political decisions.

The British people (or just over half of them) decided that even though it made no economic sense to many experts, would tie up British energies for years to come in cutting and creating red tape, and would pose immeasurable difficulties for organisations ranging from the civil service through orchestras to the NHS, the time had come to put the Great back into Britain.

It has become clear that the fault lines within the British nation are complex and by no means reducible to class difference or education. An intriguingly large number of politicians on both sides of the Brexit fence were educated at Oxford.

And the Government’s commitment to hardening borders seems to have as much to do with Britain’s island identity and distrust of globalisation as with evidence concerning national interest. When Michael Gove said that “people in this country have had enough of experts”, he was responding to the fact that appealing to emotions can be more persuasive in politics than rational evidence.

Over the many years of EU-membership, the British never overcame the tendency to refer to ‘Europe’ as a continent beyond Britain – Europe still begins at Calais. Successive governments rarely made a positive case for EU membership that might have fostered a sense of common identity or purpose.

Even the Remain camp side-lined the role of emotional factors in the nation’s decision-making, and failed to appreciate the effectiveness of a Leave campaign based on the community-building vision of enhanced national status outside a Union that was bigger than Britain, or England.

There are lessons to be learned here for the current crisis in Modern Languages. The more languages have been reduced in schools and society to being fostered only as a useful practical skill, the less they have appealed to learners who choose their subject because they enjoy them.

Like the economic arguments underpinning the Remain campaign, the argument that Britain needs language skills to improve its exports has fallen on deaf ears because it fails to touch emotions and appeal to personal identities.

The argument that language skills might one day be useful for their careers has likewise proved ill-suited to persuading young learners that the hard graft is worthwhile. If young people are to be sustained through the long process of learning a language, they need to be rewarded by a richer, more engaging experience of the many ways in which languages contribute to our lives as human beings.

When languages engage you at a deep level, they start interacting with all those human capabilities that make each human different, and each cultural group distinctive. They also interact with what makes each of us creative in an individual way. Creative Multilingualism is designed to tap into these interactions and give them space to flourish.

Nine months into the project, we can look back on a highlight that inspired hearts and minds as they transcended cultural divisions while celebrating cultural diversity – LinguaMania, which brought some 2500 people together from many cultural provenances. Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum became a setting that was alive with cultural expression – from the Afro-Brazilian samba rhythms, language tasters and cuneiform tablets to a crowd-sourced translation of Harry Potter into 52 languages contributed by the visitors in the course of the evening.

Languages build channels through time, and thankfully they don’t stop at borders any more than cultures do. Britain is no more separate from Europe linguistically and culturally than it is separate from the continent and bigger world of which it forms a part.

LinguaMania visitors looking at an Aramaic fragment of pottery experienced a glimpse of the concerns people had in Egypt around 475 B.C: “To Hoshayah: greetings! Take care of the children until Ahutab gets there. Don’t trust anyone else with them!”

And on the reverse, following a recipe for bread: “Tell me how the baby is doing!” As we renegotiate our relationships within Europe and a rapidly changing world, it’s worth thinking about the values, cultures and languages we share with ancient and contemporary peoples.

Britain right now is a good place to start exploring the multicultural and multilingual riches that are, and will remain, part of our country.'

The Red Mansion Art Prize Exhibition 2017 is on display at the Kendrew Barn in St John's College this week.

The exhibition is being presented by the Ruskin School of Art and the Red Mansion Art Foundation, and displays work by the winners of the Red Mansion Prize 2016.

The Prize is awarded to one student from each of the UK's seven leading art schools every year. Each of these students visited China for a fully-funded residency in the summer of 2016. They were given studio space and the opportunity to work alongside local artists.

The results of this work have been brought together in this week's exhibition.

This year's winner from the Ruskin School of Art is Olivia Rowland.

'The cultural experience really made me reexamine not only my own practice and processes, but the way I examine and take in the world at large - both as an artist, and as an observer,' she says.

The exhibition has been curated by Ian Kiaer, an artist and tutor at the Ruskin School of Art.

He says: 'The Red Mansion Prize provides an opportunity for selected students across seven of the UK’s major Fine Art programmes to work and exhibit together, allowing them exposure to, and dialogue with, some of their most promising peers, as well as artists in China.

'It is also significant that this is the first time the event is happening in Oxford, bringing early-career artists to the heart of the collegiate University.'

The exhibition closes this Friday (31 March) at St John's College.

DYSPK by Natalie Skobeeva

DYSPK by Natalie SkobeevaScientists have long understood how oxygen deprivation can affect animals and even bacteria, but until recently very little was known about how plants react to hypoxia (low oxygen). A new research collaboration between Oxford University and the Leibniz Institute for Plant Biochemistry, published this week in Nature Communications, has answered some of these questions and shed light on how understanding these reactions could improve food security. Dr Emily Flashman, the lead author of the study and a research lecturer at Oxford’s Chemistry Department, breaks down the key findings:

Why is this study so important?

Most living things need oxygen to survive, including plants but flooding is a major threat to agriculture and vegetation. A plant's oxygen levels are jeopardised during a flood, and they basically can't breathe. To protect themselves from flooding and survive longer, plants have a built-in stress response survival strategy, which re-configures their metabolism and supports them to generate more energy.

Scientists knew about this stress response, but they didn’t know exactly how it was controlled. Our research underpins not only an understanding of how plants respond to loss of oxygen, but also how this response could be manipulated to protect them long term. With climate change of increased prevalence in today’s society, flooding is a constant source of concern, so it is even more important for us to understand how hypoxia affects plants and crops, so that we can find new ways to preserve and protect them from it. Manipulating the enzymes involved in the process may help us to cultivate new crops and even to weather-proof them.

How does this reaction affect them?

When oxygen is in short supply a plant’s stress response effectively shuts down its metabolism, and activates an alternative pathway that allows it to live for a short amount of time, with reduced oxygen. During this time the plant has much less energy, but is still able to survive and function on a basic level. Much like when someone holds their breath underwater, their oxygen reserves allow them to survive for a short amount of time, even though they cannot breathe in fresh oxygen.

Image copyright: OU

Image copyright: OUOur research underpins not only an understanding of how plants respond to loss of oxygen, but also how this response could be manipulated to protect them long term. Manipulating the enzymes involved in the process may help us to cultivate new crops and even to weather-proof them against climate change.

What was the aim of your research?

We wanted to analyse this process, and understand how the enzymes that trigger it work. Once you know this information, you can then work out how to inhibit the enzymes and control the flood response pathway, and in doing so, keep the plant alive for longer. The overall aim being to genetically modify crops to make them flood tolerant. Understanding how these processes work is the first step in achieving this. Until now the molecular details of the plant stress response to hypoxia were not proven, but our research changes this.

Scientists understood that a plant’s response to hypoxia is controlled by ERF transcription factors, proteins which trigger changes in gene expression. In turn, the stability of the ERFs is controlled in an oxygen dependent manner by a set of enzymes, the Plant Cysteine Oxidases (PCOs). The PCOs speed up the break down (degradation) of these transcription factors, via one of the cell’s protein removal and recycling systems, called the proteasome.

Crucially, our research showed how PCOs use oxygen to work, and how this allows the ERFs to be recognised by the next step of the degradation pathway. Thus the whole pathway needs molecular oxygen to work. So in times of regular oxygen supply, the ERFs are degraded before they reach the cell nucleus and before they can activate the stress response genes. However, when oxygen is limited, as is the case during flooding, the PCOs cannot work, efficiently, so the ERFs will not be flagged for degradation and can activate the hypoxic stress response required for the plant to survive.

With climate change causing increasingly frequent flooding events worldwide, understanding how crops respond to flooding is important, in order to control or manipulate the process.

How can the findings be used to improve food security?

With climate change resulting in increasingly frequent flooding events worldwide, understanding how crops respond to flooding is important, in order to control or manipulate the process. Our research supports the understanding of this response on a molecular level – down to the role played by individual enzymes in the process. Stabilising the ERF transcription factors has been shown to enhance flood tolerance, so the targeted inactivation of the enzymes that regulate its stability may assist in cultivating crops that are able to withstand flooding longer and more efficiently.

How can the findings be built on in the future?

Now we understand what the enzymes do, we are looking further into the details of their structure and mechanism to understand precisely how they work. This will help us target the most effective way to manipulate them to artificially inhibit their activity and enhance ERF stability, first using the isolated components of the pathway before testing in plants.

Few might connect volcanic eruptions with the Nineteenth century arts and weather change, but with its varied collection of artefacts, Volcanoes, the captivating exhibition currently running at Oxford’s Bodleian Weston Library hopes to change that. ScienceBlog met with Professor David Pyle, volcanologist and the exhibition’s curator, to find out more about how he is challenging people’s perceptions of volcanoes, and how they impact the world around us.

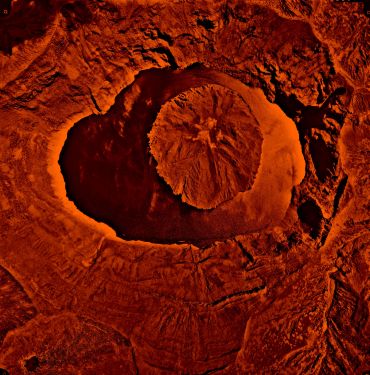

Summit crater photo of St Vincent

Summit crater photo of St VincentFalse colour air photo of the summit crater of St Vincent in April 1977. The crater contains a lava dome that was extruded into the lake in 1971.

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

What was the inspiration behind the exhibit?

About three years ago, Richard Ovenden, who is now the Bodleian’s Librarian, and Madeline Slaven, Head of Exhibitions floated the idea of doing something on the theme of volcanoes. This sounded like an exciting opportunity and we took it from there.

On a personal level, my work tends to focus on the geology of volcanoes, but recent projects in Santorini, Greece and St Vincent in the Caribbean, have looked at other records of volcanic activity. People’s stories and official accounts of the effects of volcanic eruptions tend not to be included in formal science evaluations, but they can tell us a lot about their human impact. The exhibition was as a great opportunity to share this perspective and surprise people.

What kind of insights can these records offer?

The colonial records of the St Vincent eruption of 1902 are extraordinary. One thing the colonial government was good at was keeping records, and this includes correspondence between the Governor, Chief of Police and other high level officials in London. The detail you can extract from official first-hand accounts, in terms of what actually happened, and how the eruption impacted communities, opened my eyes to the wealth of information available on how people have coped with and responded to volcanic activity in the past.

Instead of just focusing on explorers’ experiences we have included elements that shed light on tourists’, travellers’ and everyday people’s encounters with volcanoes – even those who came across them by accident.

How did you decide what to include?

I looked through around 400 objects in total, and the final exhibition features 80. Everyone had a role to play, and I spent three years burrowing through the Bodleian archives.

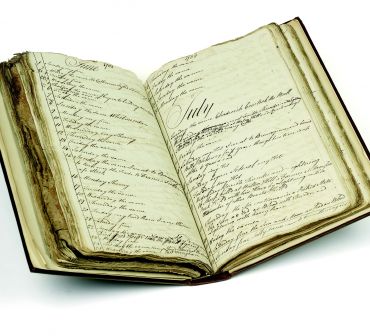

William Dunn weather diary

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

William Dunn weather diary

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries, University of OxfordWilliam Dunn’s diary for July 1783, recording the ‘putrid air’ across England following the eruption of Laki, a volcano in Iceland. It was only later, in the 1800s, that scientists began to understand the relationship between major volcanic eruptions and freak weather conditions that can occur hundreds of miles away from the site of the eruption.

As a volcanologist, I was in my element and found the volume of material incredible. Handling old books and manuscripts evokes a tangible connection between you, now and then, it’s an immense privilege to hold an object with such tremendous history.

I’m not sure what other people expect when they come to an exhibition called volcanoes, but I imagine people would envision vivid colours and descriptions of violent eruptions. The vivid colours are carried through the exhibition in its design, but the arts’ pieces selected show that volcanoes have had an entirely different impact socially. Instead of just focusing on explorers’ experiences – which are well documented, we have included elements that shed light on tourists’, travellers’ and everyday people’s encounters with volcanoes – even those who came across them by accident.

Can you tell us about the structure of the exhibition?

There are 10 differently sized cases in the exhibition - small, large, long, 3D etc. Of course we have the Bodleian’s printed materials (books and manuscripts etc.) and physical rock samples from the Museum of Natural History, but it also features things that you might not expect; Victorian poetry, art, film posters, match box lids and even tourist trinkets.

Which display are you most pleased with?

The volcano weather exhibit surprises people. An eruption takes place thousands of miles away, but its impact is often felt across the globe, through climate change. From fiery sunsets, to torrential storms, they have had great impact on the weather of the natural world. On the one hand there is the devastating immediate impact on the people living around the eruption, but the effect socially, on the other side of the world was entirely different, and often quite sublime.

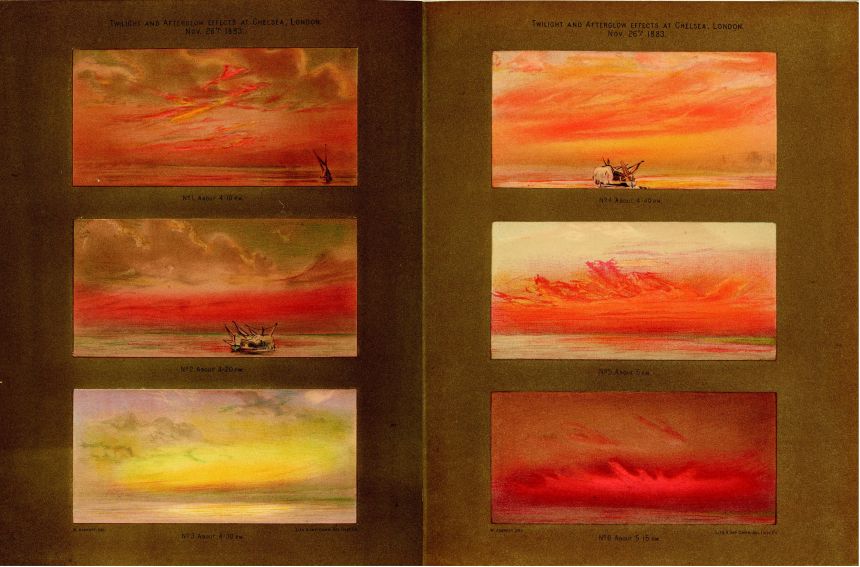

An after effect of the eruption of Mount Krakatoa in 1883 were spectacular sunsets across Europe. These sunsets were the inspiration for some of the most celebrated poetry of the time, such as Tennyson and Gerard Manley Hopkins, and stunning watercolour paintings.

People might not connect art and volcanic experience, but the sheer volume of material inspired by them, tells us a lot about international communication in the 18th century. The international telegraph network meant telegrams could be sent quickly across continents. Whether people experienced eruptions first hand, or heard about them on the social grapevine, they clearly developed their own feelings about them and expressed them in memorable ways.

Red sunsets in Chelsea

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries

Red sunsets in Chelsea

Image credit: Bodleian LibrariesWilliam Ascroft’s watercolours of vivid sunsets seen from Chelsea, London, in autumn 1883 after the great eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia. The image is found in a book called The eruption of Krakatoa and subsequent phenomena published in London in 1888 by Symons et al.

The weather diaries are fascinating, and show the impact of climate change physically and socially, at a time when no one really understood what it was.

Do any of the pieces tell us anything particularly interesting about how perceptions of volcanoes have changed?

The weather diaries are fascinating, and show the impact of climate change physically and socially, at a time when no one really understood what it was.

One from 1783 details the aftereffects of an eruption in Iceland, which triggered a hazy smog, so thick it could almost chock you. The diaries build a picture of an unbearably hot climate, complete with violent thunderstorms and an unusually red sun. Fast forward a few hundred years and we recognise these unusual weather conditions as air pollution induced climate change. But, at that time no one really knew about it, or had an explanation for the unusual weather, the explanations came later.

Professor Pyle was just seven years old when he discovered his first and fondest volcano, Villarrica, while living in Chile with his family. It has been love at first sight ever since.

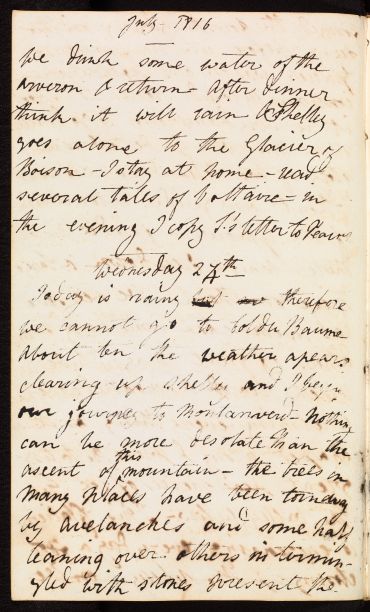

Another focuses on the impact of an eruption in 1816, which became known as the year without a summer in Northern Europe. In the Northern US conditions were so bad, it was dubbed: “Eighteen hundred and froze to death.” From the same period we have two pages of Mary Shelley’s diary, who of course wrote Frankenstein. She’s writing from Switzerland, in July 1816 - one of the worst affected places. Making these connections goes some way to explaining the morose tone and scenery depicted in the book, and the literary impact of eruptions.

Mary Shelley journal

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries, OU

Mary Shelley journal

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries, OUA page from Mary Shelley’s journal from her entry on Wednesday 24 July 1816 when she writes of the terrible rain during her holiday at Lake Geneva. It was at this time that Shelley came up with idea for her novel Frankenstein. 1816 was known as ‘the year without summer’ due to the 18165 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia. It was only in the 1800s that scientists began to understand the relationship between major volcanic eruptions and weather conditions that can occur hundreds of miles away from the eruption site.

Favourite piece from the exhibit?

One of the most significant elements is the oldest, a carbonised scroll from Herculaneum, located in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius. It is a piece of papyrus that contains a book that would have been rolled up and stored in a library in Herculaneum. It was buried by and preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD. When the library was excavated in the late 1750s, the King of Naples gave away some of these scrolls to passing dignitaries, one of whom was Prince George of England, who then gifted the scroll to the Bodleian Library.

There is something quite special about holding a volcano exhibition in a library, where the oldest item in the show is also from a library, and was preserved because of a volcanic eruption.

Storytelling is a powerful way of communicating how volcanoes behave, and starting conversations about how society can prepare for an unexpected eruption.

How did you come to be a volcanologist?

I saw my first volcano aged seven, when my family lived in Chile for a year, and I have been obsessed ever since. It’s a place where you can’t escape mountains and there are volcanoes everywhere, including my favourite, Villarrica. I’ve been back as adult, and fulfilled my childhood dream of climbing the summit and peering into the crater.

What is your proudest achievement to date?

An academic’s career is long and potentially lonely, so you have to celebrate everything along the way. I don’t look back on anything that I have done with rose tinted spectacles because there are so many things that I want to do next.

I have been very close to the exhibition for a long time, and now we have finally opened, it is delightful to see other people enjoying and responding to it.

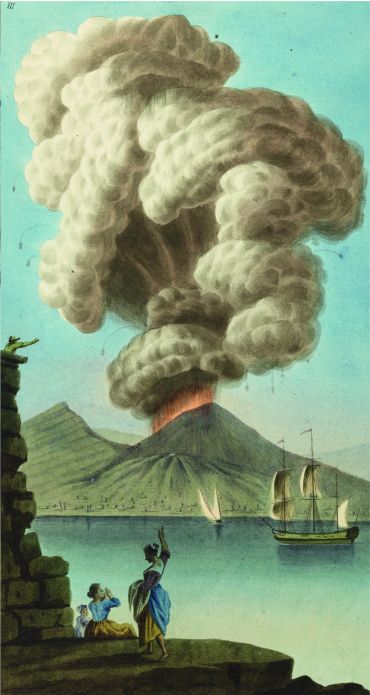

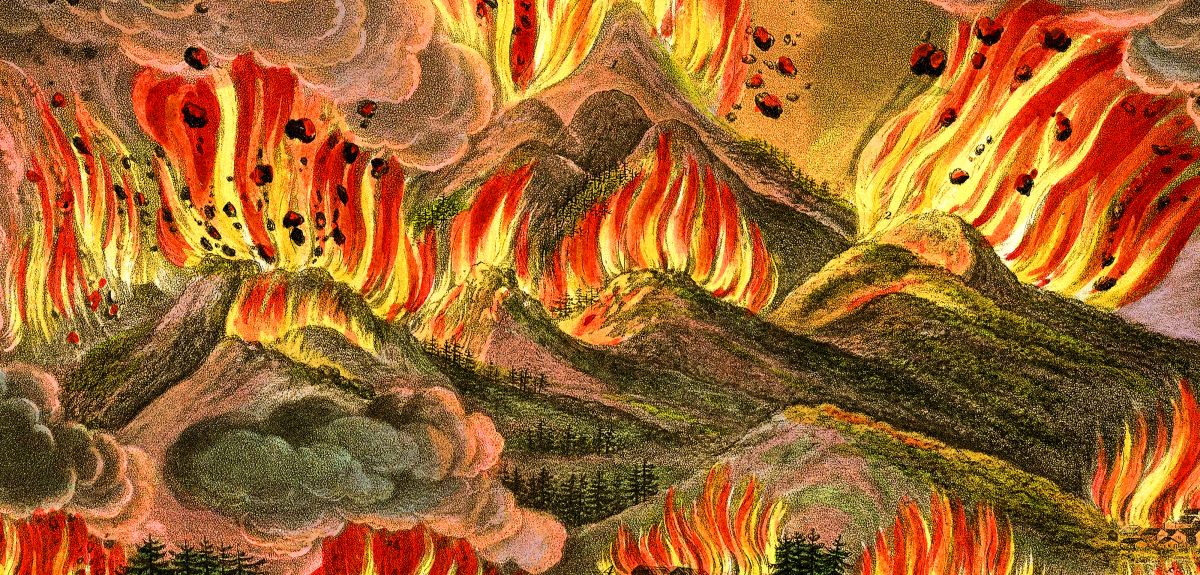

Vesuvius eruption_Campi Phlegraei

Image credit: Bodleian Libraries

Vesuvius eruption_Campi Phlegraei

Image credit: Bodleian LibrariesEruption of Vesuvius on 9 August 1779, seen from Naples. Gouache by Pietro Fabris, from the supplement to the 1779 edition of William Hamilton’s Campi Phlegraei. Hamilton (1730-1803) was a Scottish diplomat who was posted to Naples in the 18th century. From his country house at the foot of Vesuvius, Hamilton was ideally placed to witness and investigate the eruptions of the 1770s. He wrote a number of papers, books and letters documenting the 18th century eruptions of Vesuvius. Campi Phlegraei (meaning flaming fields, the local name for the area around Naples affected by Vesuvius eruptions) is a beautifully illustrated scientific treatise that contains 54 hand coloured plates by the artist Peter Fabris.

What is next for you?

My next project focuses on better telling and sharing people’s stories and experiences of volcanoes. Storytelling is a powerful way of engaging with people, communicating how volcanoes behave, and starting conversations about how society can prepare for an unexpected eruption. The official records of the St. Vincent eruption are a great testament to events, but they are not easily accessible to people actually living on the island, so impossible for them to learn from.

Storytelling is a powerful way of engaging with people, communicating how volcanoes behave, and starting conversations about how society can prepare for an unexpected eruption.

In collaboration with researchers from the University of East Anglia, who are leading a project on strengthening resilience in volcanic areas, we have been running workshops on the island, speaking to residents about their own experiences, and sharing our research.

Like many other Caribbean islands there are much more pressing needs - annual hurricane season being one of them. The volcano hasn’t actually erupted for forty years, so we were expecting it to be low on their list of priorities, but actually people have been really engaged and eager to think about it. Particularly the difference between dealing with an eruption today and forty years ago.

Image credit: OU

What is your favourite thing about your job?

It is a huge privilege to be able to work in places that are so captivating, visiting them with a purpose other than just travelling there for the sake of it. There are 60 or 80 volcanoes that erupt in any year, and often they are totally unexpected, so there is always something new to learn and look at.

• Volcanoes is running at the Bodleian Weston Library, Oxford until 21 May 2017

Our Student Focus series profiles the fascinating and varied activities of Oxford students. Miranda Reilly, an undergraduate studying English Literature, writes about balancing her studies with setting up a society for students with social anxiety, shyness and introversion.

'Starting my undergraduate English Language and Literature degree last academic year with undiagnosed social anxiety, an extreme shyness which I’d had since starting secondary school, I spent a lot of my first term feeling trapped in my room and isolated. I didn’t have much of a sense of purpose.

By around fifth week, I decided that I needed my own way to meet other students, so I set up SASI: the Social Anxiety, Shyness and Introversion Society. It was quite a success, and it was through this that I met a friend who introduced me to the Oxford University Student Union (OUSU)’s disabled students campaign, the Oxford Students Disability Community (OSDC).

My mum has been chronically ill since she was 20 with, among other conditions, an allergy to perfumes which ruled out being able to spend much time in rooms with air fresheners or rooms which had been cleaned with scented products, or around people who use scented laundry detergents and washing powders. I knew, therefore, a bit about invisible and rare disabilities before joining OSDC but little else, and hadn’t previously considered mental health as a disability.

Fast forward eleven months, and the majority of my friends at Oxford are involved in OSDC, working to improve things for themselves and other students, both through our campaigning and our socials which have created a strong community founded on accessibility and inclusivity.

Earlier this term we hosted our Disability Awareness Week, which included an arts exhibition which grew out of our fortnightly mental health art support group, Art for the Heart, and a panel of Oxford’s staff speaking on Pursuing Academia and Other University Careers – the audio and transcript for which will soon be available on our website.

Currently, we’ve been working on a Disability 101 Workshop to roll out across colleges and student societies because, while most students have good intentions, access needs are consistently forgotten about and events are often not accessible. Even if a student has excellent access to support for their academic studies, lack of access to the social and other student-run aspects of university life can lead to severe isolation and a lack of opportunities that can be added to a CV.

Later this year, our goal for UK Disability History Month (22nd November – 22nd December) is to get as many faculties, libraries and museums as possible involved, as some were for LGBTQ+ History Month, with displays and, hopefully, special lectures and talks.

Disability Studies is very much an emerging field and can be taken in many interdisciplinary directions including looking at representations of disability in literature, studying the role of music in deaf culture, and researching care for the disabled in ancient civilisations.

In my own academic studies, I am looking forward to being able to merge my interests in disability and English as I approach the final year of my degree, in which we have the most freedom to choose what we want to study, particularly with our dissertation.

Our Shakespeare paper consists of submitting three essays on any Shakespeare-related topics of our choice, and so I am certainly looking at staging disability in Shakespeare, such as with Othello’s epilepsy and Richard III’s scoliosis. Fiction – whether in the form of novels, television, cinema or another medium – has a massive impact on public perception, which can in turn lead to the very real consequences of changes to policies, laws and how people are treated in society.

Fictional portrayals of autism, for example, in addition to often portraying the spectrum inaccurately and as homogenous, have long perpetuated the stereotype that only Caucasian boys are affected, having the very real-world effect of BME people and girls on the spectrum being diagnosed at an older age, or not at all.

During my final year, I’m hoping to run for OUSU’s Vice President for Welfare and Equal Opportunities, an elected, paid position which lasts for a year after my degree and would allow me to dedicate a full-time job to working with the liberation campaigns, including OSDC, and welfare contacts across colleges.

Other than that, I’ve been looking into MA and MSc courses in Disability Studies, which go down a social policy route, but also haven’t ruled out an MA in English and a variety of career paths which do not require further academic study.

Outside of Oxford, people may assume that the university is all about academic work and nothing else, but it was only as a student here that I realised extracurriculars could be just as important and fulfilling as academic work, and could be combined with it to pursue paths which are still yet to be widely pursued.'

- ‹ previous

- 101 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria