Ian Wallman

Brexit and languages

Yesterday, Britain triggered Article 50 to begin the formal process of leaving the European Union. To mark the occasion, our guest author today is Katrin Kohl, Professor of German Literature at Oxford, who leads a major research project into languages called Creative Multilingualism.

'Creative Multilingualism – Oxford’s biggest ever Humanities research programme – got off the ground on 1st July 2016, a week after the Referendum vote to leave the European Union. The nature of the research, and the funder’s requirement that it should have an impact on UK society, have made it impossible to ignore the interplay between research and politics.

The programme is being funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council as part of their ambitious Open World Research Initiative. At a time when the political emphasis has been on strengthening borders and building walls, the only option for our research team has been to embrace the connection between research and politics as part of multilingualism’s rich tapestry.

Languages are inherently and inexorably connected with the cultures of the people who learn them, care about them, and use them. And culture is never apolitical – as we have seen in recent months, cultural identity matters, and a passion for status can drive political decisions.

The British people (or just over half of them) decided that even though it made no economic sense to many experts, would tie up British energies for years to come in cutting and creating red tape, and would pose immeasurable difficulties for organisations ranging from the civil service through orchestras to the NHS, the time had come to put the Great back into Britain.

It has become clear that the fault lines within the British nation are complex and by no means reducible to class difference or education. An intriguingly large number of politicians on both sides of the Brexit fence were educated at Oxford.

And the Government’s commitment to hardening borders seems to have as much to do with Britain’s island identity and distrust of globalisation as with evidence concerning national interest. When Michael Gove said that “people in this country have had enough of experts”, he was responding to the fact that appealing to emotions can be more persuasive in politics than rational evidence.

Over the many years of EU-membership, the British never overcame the tendency to refer to ‘Europe’ as a continent beyond Britain – Europe still begins at Calais. Successive governments rarely made a positive case for EU membership that might have fostered a sense of common identity or purpose.

Even the Remain camp side-lined the role of emotional factors in the nation’s decision-making, and failed to appreciate the effectiveness of a Leave campaign based on the community-building vision of enhanced national status outside a Union that was bigger than Britain, or England.

There are lessons to be learned here for the current crisis in Modern Languages. The more languages have been reduced in schools and society to being fostered only as a useful practical skill, the less they have appealed to learners who choose their subject because they enjoy them.

Like the economic arguments underpinning the Remain campaign, the argument that Britain needs language skills to improve its exports has fallen on deaf ears because it fails to touch emotions and appeal to personal identities.

The argument that language skills might one day be useful for their careers has likewise proved ill-suited to persuading young learners that the hard graft is worthwhile. If young people are to be sustained through the long process of learning a language, they need to be rewarded by a richer, more engaging experience of the many ways in which languages contribute to our lives as human beings.

When languages engage you at a deep level, they start interacting with all those human capabilities that make each human different, and each cultural group distinctive. They also interact with what makes each of us creative in an individual way. Creative Multilingualism is designed to tap into these interactions and give them space to flourish.

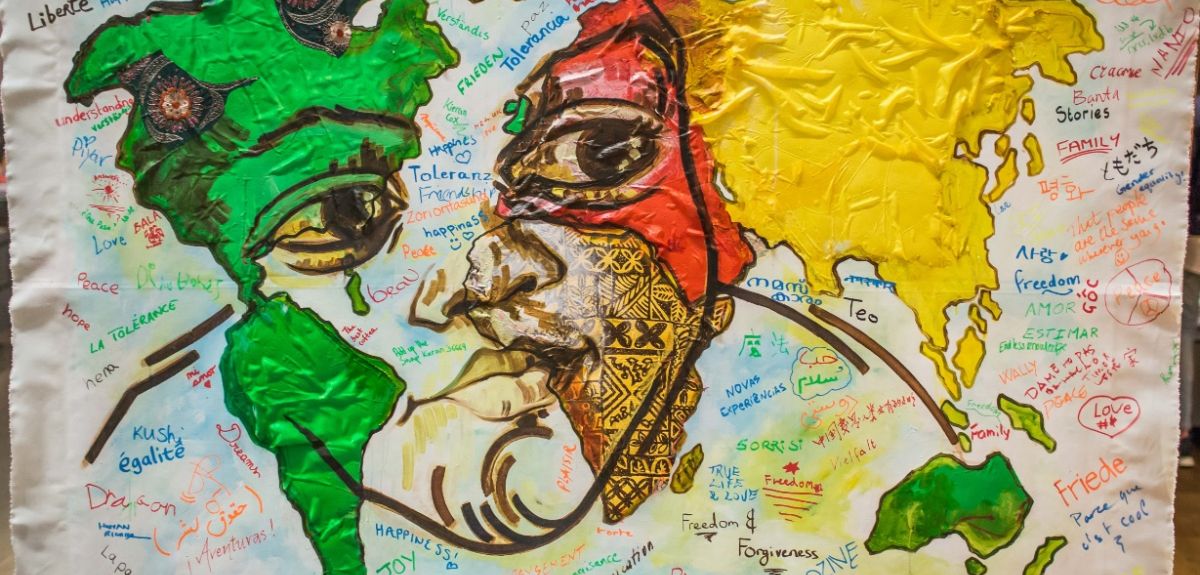

Nine months into the project, we can look back on a highlight that inspired hearts and minds as they transcended cultural divisions while celebrating cultural diversity – LinguaMania, which brought some 2500 people together from many cultural provenances. Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum became a setting that was alive with cultural expression – from the Afro-Brazilian samba rhythms, language tasters and cuneiform tablets to a crowd-sourced translation of Harry Potter into 52 languages contributed by the visitors in the course of the evening.

Languages build channels through time, and thankfully they don’t stop at borders any more than cultures do. Britain is no more separate from Europe linguistically and culturally than it is separate from the continent and bigger world of which it forms a part.

LinguaMania visitors looking at an Aramaic fragment of pottery experienced a glimpse of the concerns people had in Egypt around 475 B.C: “To Hoshayah: greetings! Take care of the children until Ahutab gets there. Don’t trust anyone else with them!”

And on the reverse, following a recipe for bread: “Tell me how the baby is doing!” As we renegotiate our relationships within Europe and a rapidly changing world, it’s worth thinking about the values, cultures and languages we share with ancient and contemporary peoples.

Britain right now is a good place to start exploring the multicultural and multilingual riches that are, and will remain, part of our country.'