Features

An Oxford academic is working with an American theatre company to test her research into how actors would have rehearsed in the time of Shakespeare.

In a book published in 2000, Tiffany Stern presented new information about the way plays would have been rehearsed in Shakespeare’s time. Since then, Professor Stern of the Faculty of English Language and Literature has been working with a theatre company which is following this model.

'A lot of people have investigated how actors performed in Shakespeare’s time, but not how they rehearsed,' Professor Stern said. 'Companies put on different plays every day because London was too small to sustain audiences for the same play. They might put on forty different plays in a season so there is no way they could rehearse each play for four weeks the way actors do today.

'Surviving parts from actors of the time reveal that they were given only their own speeches and their cues, so they would have learned their lines without knowing the full, detailed picture of the play. This makes a lot of sense because paper and scribes were expensive and there was no copyright so, if a full manuscript of your play fell into the wrong hands, someone else could perform your play.'

Having published this research, Professor Stern then learned that some theatre companies were already adopting it. She was contacted directly by the American Shakespeare Centre in Staunton, Virginia, USA.

Professor Stern explains: 'I went to talk to the ASC and meet the actors and since then we have struck up a mutually beneficial relationship. It’s given me a laboratory to test ideas about how actors would have rehearsed and performed in Shakespeare's time.

'I was interested in the texts actors read aloud on stage to save them having to learn some lines – for example, when they read out a fictional letter. I asked the actors in Stanton about this and they tried it out and came back to me to suggest that actors would have written letters out themselves.

'They explained it is hard to read alien handwriting on stage for the first time -- while writing the words in advance would help them to approximate what was said if they were given the wrong document on the night! I then found evidence that this was the case.'

She added: 'They also came up with a number of other ways that actors could have saved themselves from rote learning all their lines, for example using hats and other props to secrete text.'

Professor Stern said this model of producing plays may be beneficial for the future of performances for small Shakespeare companies. She said: 'I think we will see more and more companies start to put on plays in this fashion, partly because it saves their paying for a director, but also because it gives their actors a lot more autonomy and responsibility.

There are also artistic advantages to an actor only learning their own part. Professor Stern said: 'If your part is a humorous one, or you have a comic line, then you will act comically. But if a modern actor is playing a humorous role within a tragedy, he or she is likely to act according to the mood of the play.

'If you perform having largely rehearsed just your own part, you are likely to deliver a much richer and more varied performance of the play.'

Professor Stern added: 'It also makes us look at Shakespeare's writing in a new way. He was conceiving plays not only as a full narrative arc, but as separate strips of text with their own internal logic.'

This weekend is the last chance to see the Tutankhamun exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum. Almost 35,000 people have visited the exhibition so far, and it has been the most popular special exhibition for school groups in the history of the Museum.

The exhibition draws extensively from archival material about the discovery of the tomb, which is held by the Griffith Institute, part of the Faculty of Oriental Studies. Cat Warsi and Elizabeth Fleming of the Griffith Institute have given Arts Blog an interview about the exhibition.

The exhibition has shown the Griffith Institute to be the world’s main centre of archive material relating to the tomb of Tutankhamun. How did this come about?

Cat Warsi: About 15 years ago the then Keeper of the Griffith Institute Archive, Dr Jaromir Malek, made the decision to start an ambitious project to publish online all material housed within the Institute’s archive relating to the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun. The excavation records, created by Howard Carter and his team from 1922 to 1932, were given to the Institute by Carter’s niece, Phyllis Walker after Carter’s death in 1939.

Carter had always planned to publish a full scientific account of all the 5398 objects found in the tomb but died before he could complete it. Due to many factors, not least the outbreak of WWII, this task was not taken on by the subsequent generations of Egyptologists – new material is constantly being discovered in Egypt and there may have been a certain amount of trepidation amongst scholars to take on objects that are so well known; coupled with the understandable security measures in place to access some of the world’s most valuable works of art.

Dr Malek felt it was an unacceptable state of affairs that so little of Carter’s Tutankhamun records had been studied and hoped that by digitising thousands of notes, photographs and plans and making them freely available online, academics could incorporate the study of objects from the tomb into their research and so continue the work Carter started 80 year ago. It took many years to completely scan, catalogue and transcribe all the material, but now that it is fully accessible to everyone we are starting to see results.

Objects from the tomb are slowly being published, with more and more Griffith Institute material being citied in research and academics requesting copies of documents or visiting Oxford to work with the originals. We are currently aware of 20 academics working on objects from the tomb, with many nearing completion within the next five years. Though it may surprise people to learn that perhaps the most famous object of all, the gold mask, has never been comprehensively studied and published; this is surely the real ‘curse of Tutankhamun’.

What do you hope will be the exhibition’s legacy?

CW: The Griffith Institute is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year but, in partnership with the Ashmolean Museum, this is our first ever public exhibition. Whilst Egyptologists may know of our existence, this has given us a real public platform to engage with people and showcase some of the ‘wonderful things’ we have in our Archive. It’s given us the opportunity (in collaboration with the British Museum) to produce learning resources for families and schools which will live on and grow after the exhibition closes.

Elizabeth Fleming: Whilst sourcing archive material for the exhibition we have become aware of the ‘gap’ within our Tutankhamun Archive which documents the huge global impact the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun had on the world, from the moment of discovery in November 1922 which has continued to the present day. As a consequence the Archive is actively collecting and preserving documents such as original newspaper reports, Tutankhamun/ancient Egyptian themed advertisements, sheet music, cigarette cards, period photographs and costume jewellery.

CW: In amongst all the myths, theories and curse stories surrounding the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun we hope we’ve given the public thought-provoking facts and information from which they can decide what to believe and continue researching if we’ve sparked their interest. If we've been able to communicate just a fraction of the love and excitement we have for our subject then the exhibition will have been a success.

Do you hope it encourages young people to consider studying Egyptology and archaeology?

CW: One of the first objects visitors see when entering the exhibition is a beautiful watercolour by Howard Carter painted many years before the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Having grown up and been home-schooled in a small village in Norfolk, Carter first travelled to Egypt when he was just 17 in order to draw and paint scenes in tombs and temples.

We hope young people will be inspired by Carter’s story but that it also shows the patience, passion and dedication needed to pursue such a career. Little has changed since the 1920’s in as much as the hours are long, the jobs are few and discoveries may be a long time coming – Carter didn’t discover Tutankhamun’s tomb until he was 48!

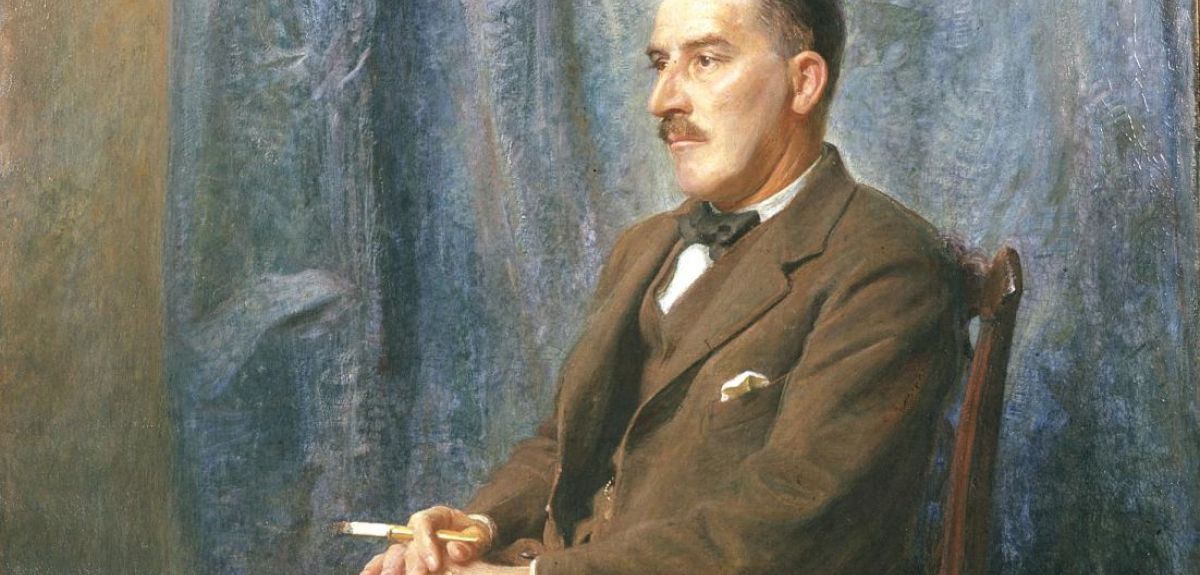

EF: The last object in the exhibition is another painting, this time the subject is Howard Carter himself. This portrait painted by Howard’s brother William, was created not long after the discovery of the tomb, he is shown seated staring into the middle distance which allows the viewer to imagine that Howard Carter is reflecting on his great accomplishment.

The curators of the exhibition invite young exhibition visitors to contemplate Howard Carter’s great achievement too, and if they are contemplating a career in Egyptology, to consider continuing Carter’s work on publishing all of the objects found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, which even now, 92 years after the discovery, leaves 70% of the tomb’s contents not properly studied and published.

How has the feedback been?

CW: We’ve been absolutely delighted with the many reviews the exhibition has received; people seem to have understood the narrative we were trying to get across and our motivations in staging ‘yet another’ exhibition on Tutankhamun, albeit from a very different angle. We all have our favourite items we hope our audience has discovered, but one of the most popular amongst reviewers seems to have been a wonderfully illustrated item of Carter’s ‘fan mail’ written by a six year old Irish boy wishing he ‘was an Egyptolisty’ like Carter. Of course feedback also highlights things we could have done better and although we may not have another exhibition in the immediate future we can apply constructive comments to archive material published on our ever expanding website.

Has the exhibition led to any unexpected results?

CW: As hoped, the exhibition has highlighted our existence amongst non-specialists and we have already received two donations of archive material from a members of the public as a consequence. We’ve received more enquiries generally concerning Tutankhamun – along with the many other benefits we hope this exhibition has made us more approachable.

The exhibition has also given us the opportunity to get in touch with old friends, including the grandson of Arthur Mace, a member of Carter’s team, who very kindly donated some family papers to the Archive.

One of our aims for the exhibition was to highlight Carter’s early work in Egypt as an artist, a passion that he sustained throughout his life but something many are not aware of. While visiting us Mace’s descendent told us a fantastic story passed on by his grandfather, that whenever Carter (a man notorious for his bad temper) had a real bee in his bonnet Mace would send him out of the tomb, telling him to go and paint in order to calm down.

EF: As many of the contemporary records for the discovery and excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun are black and white, visitors have a unique opportunity to view the treasures of the tomb without the ‘distraction’ of gold. As a consequence, we’ve been asked many more questions about the less familiar material from the tomb during tours of the exhibition.

A recurring question from visitors who were especially intrigued by a line of boat oars carefully placed in antiquity along the floor next to Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus, the oars ritualistically represented the boat that the King would use on his journey through the Underworld where he would have to face many obstacles and challenges before he was allowed to be reborn in the Afterlife. This is just one example of visitors being able to engage with the hidden gem buried with Tutankhamun, often overshadowed by the more spectacular gold items from the tomb, such as the iconic solid gold mask of Tutankhamun.

The exhibition will remain open until Sunday 2 November. A special 'Live Friday' event will be held this evening (31 October) from 7.30pm-10pm. Admission is free.

If you have been inspired by the exhibition to consider studying Ancient Egypt, Oxford University is a leading centre for undergraduate and postgraduate study in the field. More information is available here.

Zombies reportedly want to eat our brains ("BRAIIINS!") but what if we could use our grey matter to survive a zombie apocalypse?

Thomas Woolley from Oxford University's Mathematical Institute has been figuring out how maths could help us when an epidemic of the undead is unleashed – and in a fun way explore some of the maths behind the study of real life human diseases.

In a chapter in a new book, Mathematical Modelling of Zombies, Thomas and his co-authors report how their models suggest three top tips for avoiding becoming zombie chow:

1. Run! Your first instinct should always to be put as much distance between you and the zombies as possible.

2. Only fight from a position of power. The simulations clearly show that humans can only survive if humans are more deadly that the zombies.

3. Be wary of your fellow humans.

But assuming the shuffling hordes aren't already battering down your front door, I thought I’d take time out from stockpiling cricket bats, shotgun cartridges, and tinned food to quiz Thomas about maths, zombification, and watching your back…

OxSciBlog: How does zombie modelling relate to modelling real diseases?

Thomas Woolley: Mathematics can model the spread of any disease. The critical task in constructing a specific disease model lies in understanding the mechanisms by which the disease is able to spread. Canonically, zombies transmit their disease through biting a victim. Thus, like many real diseases, such as AIDS and Ebola, transmission occurs through contact with infected body fluids. As such, we model a zombie infection using the same techniques and equations that are used to model the aforementioned real diseases.

One of the main differences between zombiism and a real disease is that with a real disease there is usually some hope of a cure, treatment, or recovery. Unfortunately, this does not appear to be the case for zombification. This lack of recovery is one of the primary reasons why it is so hard to stop the apocalypse scenario that appears in numerous zombie films.

OSB: Why, mathematically, is running away from zombies a good strategy?

TW: Our model is based on the idea that zombies move around using a random walk. Explicitly, they are mindless animals that simply lurch from position to the next with no purpose or direction (we apologise for hurting the feelings of any intelligent zombies who are currently reading this). Through this assumption we find that the zombie's motion is described by the diffusion equation.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the diffusion equation. Whenever movement can be considered random and directionless, the diffusion equation will be found. This means that, by understanding the diffusion equation, we are able to describe a host of different systems such as heat conduction through solids, gases (eg smells) spreading out through a room, proteins moving around the body and molecule transportation in chemical reactions, to name but a few of the great numbers of applications.

Through the use of the diffusion equation we find that the time for a human-zombie interaction is quadratically proportional to the distance separating the humans and zombies, whilst linearly proportional to the zombie diffusion constant, which measures the rate at which the zombies move. Explicitly, this means that if you double the distance between you and a zombie, then the time before your interaction quadruples. However, if you slow the zombies down by a half then the interaction time only doubles. Hence, we see that running away, rather than slowing the zombies down, is the better way of rapidly increasing the time before an interaction.

OSB: What difference does how deadly humans are compared to zombies make?

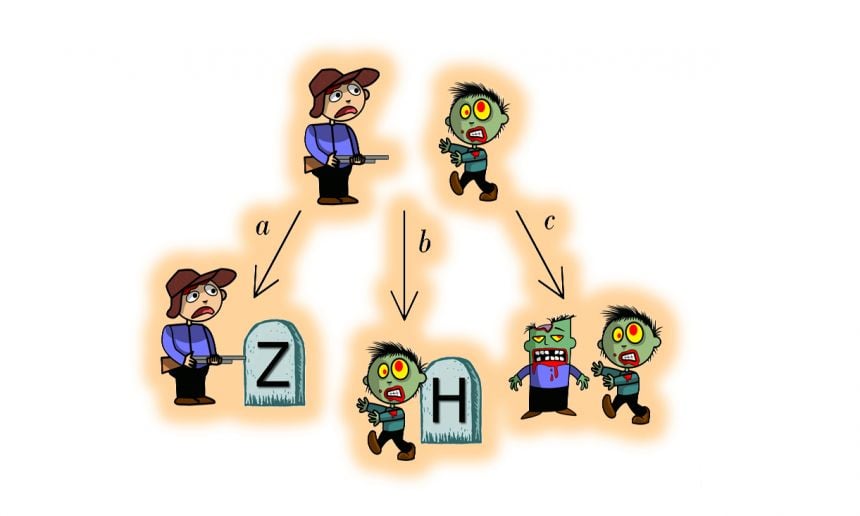

TW: In our model we suppose that there are three different interactions that can occur:

humans kill zombies at a rate a;

zombies kill humans at a rate b;

humans become zombified at a rate c.

These interactions are illustrated in the figure below. The only way that humans can survive is if we can wipe out the zombie menace. If any remain then they will always represent a potential threat. This means that humans have to kill the zombies at a rate faster than they are created, explicitly we need the rate a to be great than the rate c. Unfortunately, if the zombies are very infectious and very resilient to our attacks then c will be greater than a and we find that an infection wave can take hold in the susceptible population. This results in a scenario where everyone is eventually wiped out.

Illustration of three possible zombie interactions considered in the model

Illustration of three possible zombie interactions considered in the modelPhoto: Thomas E Woolley, with thanks to Martin Berube who provided the zombie figures.

OSB: Why might maths suggest that you turn on your fellow humans?

TW: An infection wave can only happen if there are susceptible people to be infected. Critically, the speed of the infection wave depends explicitly on the initial number of susceptible people. If you are able to isolate yourself geographically on an island then you should be completely safe (excluding such cases that occur in the film Land of the Dead).

However, suppose you are not lucky enough to live on an island and, instead, you in an office block when the dead begin to rise. Everyone around you is a potential zombie. Thus, be careful to pick your colleagues carefully. If they are all weak then you might want to think about dispatching them.

Alternatively, if you are the weak connection, make sure that someone is not trying to get rid of you. Of course I and the other authors would not recommend such unethical behaviour. The population will have enough trouble trying to survive the hordes of undead, without worrying about an attack from their own kind!

People involved in arts and sciences around Oxford are joining forces to hold a festival on the theme of breath and breathing next Saturday (1 November). The one-day Breath Festival comprises events, talks, performances and exhibitions in venues across Oxford.

Oxford University will curate a series of free 'Breath Talks', a series of TED-style short presentations by academics and artists on all the ways in which breath speaks to us. Dr Emma Smith, a Shakespeare expert at the University, will talk about King Lear and the relationship between language, performance and breath. Dr Kevin Hilliard of the Modern Languages Faculty will talk about the ways in which 18th Century German poems enact heavenly breathing patterns in their verse.

During the day Oxford University's museums will put on special displays, performances, tours, talks and children's activities concerned with breath. Visitors can also take 'Breath Tours' of the Museum of Natural History and Pitt Rivers throughout the day. The Museum of Natural History will host a session of singing activities led by Singing for Better Breathing, a local Sound Resource project encouraging people with respiratory problems to sing.

In the evening two performances of a new composition, Breathe, will take place at the North Wall Arts Centre. Breathe was composed by Orlando Gough, having been developed through research with John Stradling, Emeritus Professor of Respiratory Medicine at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. The composition marks the tercentenary of the death of Dr John Radcliffe, who generously donated the funds to enable the building of the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford’s first hospital.

Professor Abigail Williams, an English academic at Oxford University, said: 'The Breath Talks are an eclectic and inspiring collection of talks from experts in many different disciplines. From King Lear to wind turbulence, devotional verse to Inuit breath music, they will explore how breath has been thought about, illustrated and performed throughout history.'

Lucy Shaw, Manager of Oxford University Museums partnership, said: 'Oxford University Museums are really delighted to be part of the Breath Festival. The activities, performances and displays, which make up the festival, bring together original work and thinking of artists, scientists, academics and curators in order to inspire, excite and inform our audiences.'

The Breath Project has been developed by artlink, the arts programme for Oxford University Hospitals Trust, in conjunction with Oxford University’s Humanities Division, Oxford University Museums, Oxford Contemporary Music and Singing for Better Breathing. It is supported by ORH Charitable Funds, The Radcliffe Trust, a Wellcome Trust Arts Award and Arts Council England.

Stammering is a common condition in children that may last into adulthood and can affect people's self-esteem, education and employment prospects.

22 October is International Stammering Awareness Day and sees the launch of a new Oxford University trial investigating whether a form of non-invasive brain stimulation could help people who stammer achieve fluent speech more easily and make this fluency last longer.

I asked Kate Watkins and Jen Chesters of Oxford University's Department of Experimental Psychology, who are leading the new trial, about the science of stammering, what the trial will involve, and how brain stimulation could improve current therapies…

OxSciBlog: What is stuttering/stammering? How many people have a stammer?

Kate Watkins: Stammering (also known as stuttering) affects one in twenty children and one in a hundred adults. About four or five times more men than women are affected.

The normal flow of speech is disrupted when people stammer. The speaker knows what he or she wants to say but has problems saying it. The characteristics of stammering include production of frequent repetitions of speech sounds, and frequent hesitations when speech appears blocked. Children and adults who stammer can sometimes experience restrictions in their academic and career choices. Some people some suffer anxiety as a result of their speech difficulties.

OSB: What do we think causes people to stammer?

KW: The cause of stammering is unknown. Using MRI scans we have noticed small differences in the brains of people who stammer when compared with those of people who speak fluently. For example, we found differences in the amount of brain activity that occurs during speech production in people who stammer even when they are speaking fluently.

These brain imaging studies indicate abnormal function of brain areas involved in planning and producing speech, and in monitoring speech production. We have also used MRI scans to look at how these brain areas are connected and found that the white matter connections between these regions are disrupted in people who stammer.

A striking feature of stammering is that complete fluency can be achieved by changing the way a person perceives his or her own speech (so by altering the way the speaker hears his or her own voice). For example, masking speech production with noise (or loud music as demonstrated in the film The King's Speech or by Musharraf on Educating Yorkshire) can temporarily eliminate stuttering. Delaying auditory feedback of speech, altering its pitch, singing, speaking in unison with another speaker, or speaking in time with a metronome are all ways of temporarily enhancing fluency in people who stammer. These observations tell us that the cause of stammering may be due to a problem in combining motor and auditory information.

OSB: What treatments/therapies can people currently get for stammering?

Jen Chesters: Speech and Language Therapy for people who stammer may involve learning to reduce moments of stammering, or decrease the amount of tension when stammering. Techniques such as speaking in time with a metronome beat, or lengthening each speech sound can immediately increase fluency.

However, these approaches make speech sound unnatural, so moving towards fluent yet natural-sounding speech is the main challenge during therapy. Even when these methods are mastered within the speech therapy clinic, continual ongoing practice is needed for fluency to be maintained in everyday life. The fluency-enhancing effects can also just 'wear off' over time, even when these techniques are practised regularly. For all these reasons, therapy for adults who stammer often focuses instead on learning to live with the disorder.

OSB: How might brain stimulation improve on these?

JC: Non-invasive brain stimulation is a promising new method for treating disorders that affect the brain's function. The method we use is called transcranial direct current stimulation (or TDCS for short). TDCS involves passing a very weak electrical current across surface electrodes placed on the scalp, and through the underlying brain tissue (it doesn't hurt!). This stimulation changes the excitability of the targeted brain area. TDCS applied during a task that engages the stimulated brain region, can increase and prolong task performance or learning.

TDCS has been used in rehabilitation studies, for example it has been applied to brain regions involved in speech and language to increase these functions in patients who have problems with speech (aphasia) following a stroke. We are interested in how TDCS could help people who stammer to achieve fluent speech more easily, and maintain their fluency for longer. TDCS may have the potential to increase speech therapy outcomes, or to reduce the high levels of effort and practice that are needed in traditional speech therapy for stammering. Our research aims to explore this potential.

OSB: What is the aim of your new trial?

JC: In this study, we want to see how the effects of a brief course of fluency therapy might be increased or prolonged by using TDCS. We will use some techniques that we know will immediately increase fluency in most people who stammer, such as speaking in unison with another person or in time with a metronome. However, these techniques would normally need to be combined with other methods to help transfer this fluency into everyday speech. We will investigate how TDCS might help maintain the fluent speech that is produced using these methods.

OSB: What will volunteers be asked to do?

JC: Volunteers will be invited to have fluency therapy over five consecutive days, whilst receiving TDCS. In order to measure the effects of this intervention, they will also be asked to do some speech tasks before the fluency therapy, one week after the fluency therapy, and again six weeks later. We are also interested in how this combination of therapy and TDCS may change brain function and structure. So, volunteers will also be invited for MRI scans before and after the therapy.

OSB: How do you hope the trial results will benefit patients/your research?

JC: The results of the trial will give us a first indication about whether TDCS might be a useful method to develop for stammering therapy. The research is in its early stages, so the results of this study will not cross over into the speech therapy clinic just yet. However, we are hoping to see whether TDCS shows promise for improving speech therapy outcomes. If it does, further research would be needed to explore how TDCS can be combined with speech therapy to achieve the greatest improvements for people who stammer.

- ‹ previous

- 160 of 252

- next ›

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria