Why sleep could be the key to tackling mental illness

![]()

Russell Foster, Professor of Circadian Neuroscience, University of Oxford

We are only beginning to unravel the genetic and biochemical basis of mental illness – a vague term including conditions as diverse as anxiety, depression, and mood and psychotic disorders. With millions of people suffering from such conditions, it is crucial that we find ways to improve diagnosis and treatment. But an increasing body of scientific evidence is now suggesting that we should turn our attention to one of our most basic functions: sleep.

Studies suggest that disrupted sleep such as insomnia could actually help us predict episodes of mental illness and that fixing sleep problems may help treat them. Despite this, the effects of sleep on mental illness have been largely ignored in the clinic so far. But how is sleep and mental health actually linked in the brain? To understand this, let us first consider the biology of sleep and circadian rhythms.

Circadian rhythm and health

There have been over a trillion dawns and dusks since life began some 3.8 billion years ago. The physiology, metabolism and behaviour of organisms, including us, are aligned to this daily cycle through internal clocks which enable us to effectively “know” the time of day. This clock also stops everything happening at the same time and ensures that biological processes occur in the appropriate order. For cells to function properly they need the right materials in the right place at the right time.

Thousands of genes have to be switched on and off in order and in concert. Proteins, enzymes, fats, hormones and other compounds have to be absorbed, broken down, metabolised and produced in a precise time window to allow important processes such as growth, reproduction, metabolism, and cellular repair. These take energy and all have to be timed to best effect by the millisecond, second, minute and hour of the 24-hour day.

Circadian rhythms are innate and hard-wired into the genomes of just about every living thing on the planet. In humans, our physiology is organised around the daily cycle of activity and sleep. In the active phase, when energy expenditure is high and food and water are consumed, organs need to be prepared for the intake, processing and uptake of nutrients.

During sleep, although energy expenditure and digestive processes decrease, many essential activities occur including cellular repair, toxin clearance, memory consolidation and information processing by the brain.

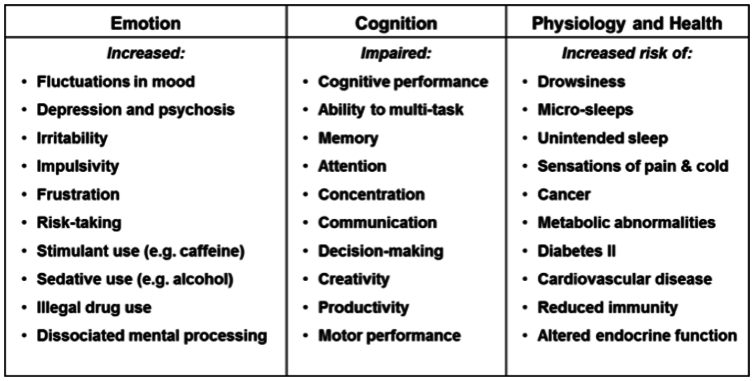

Disrupting this pattern, as happens with jet-lag, shiftwork, and mental illness breaks down the internal synchronisation of the circadian network and our ability to do the right thing at the right time is greatly impaired. This can have a major impact on our health, with some of the effects described in the table above.

Sleep disruption in mental illness

The relationship between mental illness and sleep and circadian rhythm disruption was first described in the late 19th century by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin. Today, such disruption is reported in as many as 80% of patients with schizophrenia, and is increasingly recognised as one of the most common features of the disorder.

Yet despite its prevalence in mental illness, sleep disruption has been largely ignored, dismissed as a consequence of either social isolation, lack of employment, anti-psychotic medication. However, our team has explored this assumption and showed that sleep and circadian-rhythm disruption in patients with conditions such as schizophrenia persists independently of anti-psychotic medication and that it cannot be explained on the basis of social isolation or lack of employment. These results led us to suggest that mental illness and sleep disruption may share common and overlapping pathways in the brain.

The sleep and circadian timing system is the product of a complex interaction between multiple brain regions, neurotransmitters and hormones. As a consequence, abnormalities in any of these neurotransmitter systems will likely have an impact on sleep and circadian timing at several levels.

Similarly, psychiatric illness arises from abnormalities in the interacting circuits and neurotransmitter systems of the brain, many of which will overlap with those regulating sleep and circadian rhythms. Viewed in this way, it is no surprise that sleep disruption is common across the mental illness spectrum, or that disruption of circadian biology might worsen a fragile mental health state. Very significantly, many of the health problems caused by sleep disruption are common in mental illness, but have almost never been directly linked to the disruption of sleep.

These insights enable us to make important predictions. For example, genes linked to mental illness should play a role in sleep and circadian rhythm generation and regulation and genes that generate and regulate sleep and circadian rhythms should play a role in mental health and illness.

To date a surprisingly large number of genes have been identified that play an important role in both sleep disruption and mental illness. And if the mental illness is not causing disruption in sleep and circadian rhythm, then sleep disruption may actually occur just before an episode of mental illness under some circumstances.

Sleep abnormalities have indeed been identified in individuals prior to mental illness. For example we know that sleep disruption usually happens before an episode of depression. Furthermore, individuals identified as “at risk” of developing bipolar disorder and childhood-onset schizophrenia typically show problems with sleep before any clinical diagnosis of illness.

Such findings raise the possibility that sleep and circadian rhythm disruption may be an important factor in the early diagnosis of individuals with mental illness. This is hugely important, as early diagnosis offers the possibility of early help. It is also plausible that treating the actual sleep problems will have a positive impact upon the level of mental illness. A recent study managed to reduce sleep disruptions using cognitive behavioural therapy in patients with schizophrenia who showed persecutory delusions and found that a better night’s sleep was associated with a decrease in paranoid thinking along with a reduction in anxiety and depression. So the emerging data suggests treating sleep problems can be an effective means to reduce symptoms.

So where do we go from here? It is now abundantly clear that sleep problems in mental illness is not simply the inconvenience of being unable to sleep at an appropriate time but is an agent that exacerbates or causes serious health problems. Understanding the nature of sleep disruption in mental illness, and developing evidence-based therapeutic interventions using cognitive behavioural therapy, appropriately timed light exposure and some exciting new drugs to stabilise circadian rhythms is a major focus of the work currently being undertaken in Oxford.

It is time we began to take seriously the importance of sleep across all sectors of society, and particularly in mental illness. Treating sleep problems in mental illness will not only improve the health and quality of life for countless individuals and their caregivers, but will also have a massive impact on the economics of health care.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.