Monitoring, evaluation and learning for policy engagement: approaches, questions and resources

The first note in this series suggests some principles for researchers and others looking to learn about and improve their engagement with the policymaking community. This second note explores these principles and highlights tools that they can use from the outset. These and other tools can also be found in our resource library.

This guidance note is also available in PDF format:

Strategising up front, or at an early stage

1. Start early

It’s tempting to assume that evaluation comes towards the end of a research project. Indeed many associate it with a somewhat painful process of producing reports for a funder, or an accountability exercise. Increasingly, though, many of us see it as a means of continually learning and adapting in the light of changing circumstances.

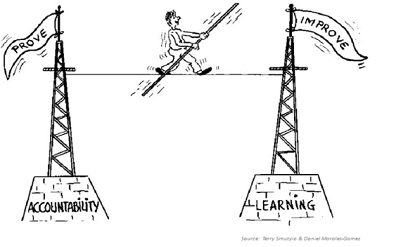

Most evaluators will tell you that walking the tightrope between ‘prove’ and ‘improve’ can be difficult. However, many researchers engaged with public policy recognise that establishing effective processes for learning is key to not only improving what they are doing, but also to meet some of the demands upon them to demonstrate their impact.

Effective monitoring and evaluation requires up-front investment in thinking through what policy engagement is designed to achieve. As well as who might be involved, how this might be done, and what kind of learning processes might be best suited to assessing progress. This means seeing monitoring and evaluation as an integral part of the research and engagement process, not something separate. It provides a feedback loop that allows promising avenues to be widened, and less promising pathways to be narrowed or ruled out.

Effective monitoring and evaluation requires up-front investment in thinking through what policy engagement is designed to achieve. As well as who might be involved, how this might be done, and what kind of learning processes might be best suited to assessing progress. This means seeing monitoring and evaluation as an integral part of the research and engagement process, not something separate. It provides a feedback loop that allows promising avenues to be widened, and less promising pathways to be narrowed or ruled out.

Freedom for academics to spend time on planning for [policy] impact is very important. The Policy Engagement Team can help in pushing for more space for this at early stages in the lifecycle of a project.

Senior Researcher, Social Sciences Division

The language of monitoring and evaluation, including distinctions between ‘outputs’, ‘outcomes’ and ‘impacts’, can often be off-putting and feel alienating to some researchers. Some associate it with tick-box exercises and form-filling. Yet the worlds of evidence, knowledge and learning which are the bedrock of effective monitoring and evaluation, are those which researchers inhabit and engage with on a daily basis.

Starting early

Starting early with planning, and associated monitoring and evaluation, provides researchers with a number of benefits. It:

- establishes a platform for proving and improving;

- creates the feedback loops and ‘intelligence’ to allow for adaptation; and

- allows them to familiarise themselves with monitoring and evaluation in ways that build on and validate their knowledge and experience.

Key resource

ROMA: a guide to policy engagement and policy influence, Overseas Development Institute

2. Acknowledge complexity, context and luck

Public policy can be disorderly, both in design and implementation. The non-linear, complex nature of the policy process means that mapping out a detailed plan for change is not likely to survive first contact with policymakers. Much of the literature therefore suggests such engagements require ‘a compass not a map’, or approaches which involve learning by doing and ‘making small bets based on educated guesses’. This echoes the almost intuitive ways of working described by a number of respondents in our interviews, one of whom described the policy engagement process like navigating ‘a kind of very muddy, slow tidal river’.

As a number of monitoring and evaluation specialists have noted, this requires approaches which place less emphasis on pre-determined indicators of change, and more emphasis on generating some initial assumptions, or ‘theories of change’, which in turn inform ‘educated guesses’. Using a theory of change means that monitoring and learning is geared more towards supporting iterative learning and revision of assumptions, than assessing progress against a set of rigid performance criteria. ”

We don’t report 98% of the policy work we do, since the eventual impact is cumulative and additive over a period of time, many meetings take place and only a few lead to meaningful follow-up or impact. It amounts to placing many bets. Policy engagement is only partly effort and skill. Luck and timing also key.

Senior Researcher, Social Sciences Division

We should also bear in mind that outcomes from policy engagement are, to a greater or lesser extent, determined by context and chance as well as the skills, knowledge and experience of the researcher. In games such as poker, the associated risk is known as ‘resulting’: the danger of assuming that the outcome of a given hand reflects the quality of decision-making of its player, as opposed to chance.

In the same way, assessing the effectiveness of policy engagement on the basis of policy outcomes runs the same risks. A theory of change can help navigate these conditions of uncertainty, by not drawing too tight a connection between the policy engagement process and the impact that is achieved.

Questions for creating a theory of change

- Whether you develop a detailed theory of change or not, the following questions can be useful in generating more ‘educated guesses’ as a starting point for learning by doing: Why do you want to engage?

- How do you assume policy change happens in this area?

- Who do you need to engage with?

- How might you engage them?

- What would you need to do that?

- What might success look like?

Key resources

- Guide to working with Theory of Change for research projects (Vogel, 2012)

- Theories of Change to inform Advocacy and Policy Change Efforts (Stachowiak, 2013)

3. Think about relationships, power and politics

Policies are forged in a crucible of vested interests. Evidence is just one of the many contributions that compete for the oxygen of attention. Researchers are just one of the actors on the policymaking stage, along with a much larger cast of characters. This can present a tangled, evolving and even daunting web of relationships.

Understanding the key players, what makes them tick, and how they relate, is important for effective engagement as well as for tracking change over time. In the first instance this means identifying not only who is involved in the policymaking process, but also those that will be affected by the outcomes, whether positive or negative. It also requires an understanding of their relative influence and power, and the degree to which they are liable to be supporters or blockers of the use of your research. Processes of power mapping can be used to do this in a straightforward way.

Not only does a mapping process reveal potential allies, it is also the first step in understanding potential influence channels, whether they be direct or indirect, formal or informal. This in turn can help determine whether a formal face-to-face meeting with a decision-maker, a well-placed opinion piece, an informal word with an advisor, or a mix of these, is the best starting point for engagement. Understanding the constraints policymakers face, the context they are working in, and their core beliefs, can also help you think about how you might frame your research or findings.

You need a good understanding of the psychology of politicians i.e. the COM-B model of behaviour change (capability, opportunity & motivation). This is key in the policy space.

Senior Researcher, Medical Science Division

None of this guarantees success in changeable political environments, or ensures that your initial method of engagement or framing is going to be effective. But it can make your initial guesses more educated, as well as help set up more systematic processes of learning and adaptation.

At this early stage of engagement ‘reading the room’, picking up ‘soft signals’ and observing how others are reacting to your engagement, provides important yet subtle feedback. Are people agreeing to another meeting? Are they inviting you into a process which might benefit from your research? Or recommending your work to others?

The answers to these questions might suggest the need to adjust your strategy, or how you are framing the issue. It might indicate that the timing is wrong, or you are not engaging with the most appropriate people or group. These considerations improve the odds for your next ‘bet’, and even a brief record of these engagements can contribute to a longer-term account of how your evidence and expertise is making a difference.

Key resources

- Everyday Political Analysis (Developmental Leadership Program, 2016)

- Stakeholder Influence Mapping (Jacques-Edouard Tiberghien, 2012)

Monitoring and learning by doing

4. Track contacts, networks and coalitions

Policy engagement is all about relationships: investing in them, maintaining them and, from time to time, ending them. It is also often about building broader interest groups or coalitions.

Keeping track of how these relationships are evolving is essential to learning and adapting as you go, as well as being able to tell the story of how outcomes occur. We can be inclined to focus on a ‘two-player’ game, involving researcher and policymaker, but there are usually more players than we think. Keeping at least one eye on the relationships between them can be very helpful. This has two main benefits: a) it provides intelligence about the changing nature of interests and alliances, which might suggest adaptations to how you engage and who with; b) it may also allow the broader significance of your research to be revealed or discovered. There are three main ways this can be done:

- Keep a simple timeline or research diary. These record key observations and changes in real time to help the sense-making process at a later date, and allow the capture of more vivid interactions or changes in context. No need for complex spreadsheets, necessarily: pen and paper may do, and email or social media apps like WhatsApp, Facebook or Evernote may be even better if you’ve colleagues to share with. Simple tools can result in a greater likelihood of this kind of information being recorded, shared and used.

- Revisit and update your ‘power map’. This can help reveal changing relationships and influences. More formal social network analysis is also an option here, as are more participatory mapping exercises, both of which can done in ways that produce ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures of change.

- Keep monitoring the evolving context in which you are working. Public attitudes, as well as the political and economic environment, shape policymakers’ room for manoeuvre. Your research may suddenly acquire salience, or just as suddenly fall outside the Overton window i.e. the range of politically feasible policies.

Developing these relationships…developing these networks…pitch[ing] the project to get initial feedback…and creat[ing] a space for myself…that sounds evil and strategic but I guess I have planned it out...

Senior Researcher, Humanities Division

Questions for unpacking relationships

Asking these questions throughout the project, for example as a self-reflection exercise or in a team meeting, and documenting some of the answers will put you in a good position to remain relevant as well as explore your contribution to the process.

- How are relationships changing in the community of interest?

- Are new alliances and coalitions emerging?

- Are changes in context shifting how your research is received?

- What adjustments might need to be made to your policy engagement?

Key resource

Evaluating Coalitions and Networks: Frameworks, Needs, & Opportunities (Mona Younis, 2017)

5. Track outcomes and impacts – explore multiple pathways

Changes in ideas, behaviours, policies or practices are usually the result of a combination of factors. Like the making of laws or sausages, it is a messy process. The contribution of evidence and your engagement are likely to be pieces of a larger jigsaw. Your engagement might be focused directly on policymakers or be more oblique or indirect.

There has been long debate amongst evaluators, and those studying research impact, about the difference between the direct, ‘instrumental’, route to change in policy or practice, as opposed to the more indirect, ‘enlightenment’ pathway, in which ideas accumulate or are absorbed over time, in ways that shape the policy environment and the conceptual frameworks of policymakers. Others have pointed to the ways that policy engagement can contribute to changes in the capacities and attitudes of those involved, as well as building trusted connections between researchers and policymakers. These types of change, it is argued, are not only important in explaining how policy or practice has changed, but can also indicate how those deeper relationships might lead to outcomes in the future.

The training that the social sciences division did in 2016/7 … was really helpful. It gave a nice introduction into impact and how you start document it. I never realised before how documenting that was important.

Post-doctoral Fellow, Social Science Division

Research funders classify policy change in different ways. Some may consider it as an ‘impact’, whereas other funders call it an ‘outcome’, reserving the term ‘impact’ for the ultimate effects of policy or practice change, such as changes in the wellbeing of a given population, or reductions in carbon emissions.

In any case there are various sophisticated tools or methods that can be used to capture outcomes, and analyse the contribution of policy engagement to these changes. Many of these can require additional resources or expertise – something one should consider budgeting for, where they are needed.

Fortunately, there are also some simpler tools, such as outcome harvesting or bellwether interviews, which are particularly appropriate for processes where cause and effect seem too difficult to connect in advance, and too tangled to unravel after the fact. In combination with research diaries, these methods allow for claims to be verified by working ‘backwards’ from an outcome to the combinations of factors that may have contributed to bringing it about.

Changes to what?

Whilst it is always important to be clear about the terminology funders use, there will be multiple pathways to change. These are useful ways of thinking about them:

- Instrumental: changes to plans, decisions, behaviours, practices, actions, policies

- Conceptual: changes to knowledge, awareness, attitudes, or emotions

- Capacity: changes to skills and expertise

- Culture/attitudes towards knowledge exchange, and research itself

- Connectivity: changes to the number and quality of relationships and trust

Key resource

Outcome Harvesting Documentation, Case examples and Website

Evaluation and reflection

6. Make space for learning and reflection

Making sense of the array of evidence that engaging in policy processes can generate can require the skills of Sherlock Holmes, the teamwork of the Beatles, and enough time and space to bring these together. This might involve a data party, an after-action review, or an outcome assessment exercise.

One of the key challenges of telling a story of your engagement is that policymakers may be reluctant to acknowledge that you, or your work, has been influential. Such an admission may not always be in their interest. In any case, it is rarely possible to control for this variable by running one policy process with your engagement and the same one without it, and measure the difference. Both of these factors make it harder to attribute particular outcomes to your engagement.

This is why contribution analysis has been used to explore more complex processes – like the generation of policy outcomes – which have many causal factors. This method uses a number of steps and can be done to various levels of sophistication. Critical parts of the process include assembling your contribution story and assessing its credibility, weighing it up against plausible alternative explanations for observed outcomes.

So, I think that would be my main learning process that having kept a diary would have been useful… in terms of… reflection and what might be the next steps.

Senior Researcher, Humanities Division

The learning or sense-making process can also be focused on different levels or loops. Single-loop learning focuses on activities, and whether they are being done well or according to plan. Double-loop learning explores whether the activity is the right one in the first place. And triple-loop learning asks more fundamental questions about the learning process itself, and how one decides what is ‘right’.

At the same time even strategic learning may not lead to changes or adaptations to approach. Investing in action learning sets, and developing a culture of knowledge sharing can provide not only the motivation to turn learning into action, but also create peer accountability to do so.

Reflective questions

One of the most challenging aspects of learning as you go is protecting the time needed to do so. Some organisations have created ‘at-home weeks’ which are focused on reflection, shared learning and planning adjustments. These are useful for busy, dispersed teams that are often ‘away’. Some overarching questions that might be useful for teams to ask regularly:

- Are we doing the thing right?

- Are we doing the right thing?

- How do we decide what is right?

- What will we do differently as a result?

Key resource

The National Health Service Learning Handbook (tools and resources section)

7. Ensure evaluation is fit for purpose

Whether evaluations are done for learning or accountability, or other reasons, researchers will want to see the investment in evaluation pay off. Having people who care about an evaluation is an important predictor of its findings being used. Other research also suggests that effective interaction between evaluation clients and evaluators is also critical to the meaningful use of evaluations. As such, being clear about purpose and who is involved is the key to designing an appropriate evaluation which is likely to be robust but also useful.

Traditionally, the theoretical distinction between monitoring (i.e., the routine collection of data of what is, or is not, going well) and evaluation (i.e. the periodic assessment of the overall merit or worth of an activity and its effects, or impact) is clear.

Researchers understand that they need evidence, but [not] actually what that means practically in terms of the steps that they need to put in along the way…[for] evaluation.

Research Facilitator, Social Sciences Division

In practice, however, in complex contexts, these processes often overlap. What is, perhaps, more important than these distinctions is the recognition that routine collection of data on policy engagement is needed for more in-depth analysis of how outcomes happened to be done well.

Types of evaluation

- Formative: undertaken during an intervention

- Summative: undertaken after the end of an intervention, often called a ‘final evaluation’

- Developmental: undertaken during an intervention to provide near real time feedback to innovative projects

- Impact: focused on ultimate long-term effects of an intervention, whether positive or negative, intended or unintended

One of the essential purposes of most evaluations is to assess the contribution of your engagement to change. This often includes an exploration of how contextual factors combined with that engagement in specific ways. Such analysis of what some call ‘causal mechanisms’ helps us to understand not just what has changed, but how and why. All of which can help us place better bets the next time round and provide practical guidance to policymakers and practitioners.

Of course, none of this will happen if evaluation findings are not communicated effectively. This means thinking carefully about reporting and communications, and how best to reach audiences in ways that will increase the chances of findings being used.

Evaluation questions

- Are the purpose and evaluation questions clear and agreed?

- Are the methods appropriate to answer the questions and for the resources available?

- Are effective management and governance of the evaluation in place?

- Are strategies for the use of findings established?

Key resources:

- A practical guide to advocacy evaluation (Innovation Network)

- How to design a monitoring and evaluation framework for a policy research project (ODI)

The final note in the series explores the strategic importance of these activities in the context of policy engagement and impact for both individual researchers and the University of Oxford.

Guidance note 2 of 3 on Monitoring, evaluation and learning for policy engagement.

Prepared by Chris Roche, Alana Tomlin & Ujjwal Krishna, November 2020.