Features

Alessandra Enrico Headrington, COMPAS

Alessandra Enrico Headrington, COMPAS

The United States’ intervention in Venezuela on 3 January 2026 marks a critical moment not only for the country’s political trajectory, but also for the future of one of the largest displaced populations in the world.

The situation before US intervention

The United States’ intervention in Venezuela has ignited questions about its legality under international law and the principles set out in the United Nations Charter. This moment reflects a broader trend in which core legal principles appear increasingly subordinated to power politics. Beyond questions of legality, it also raises deeper uncertainties about Venezuela’s political future and what leadership change might mean for the possibility of return for nearly 8 million Venezuelans displaced since around 2015.

Of the majority of those displaced, around 6.9 million are hosted by countries in Latin America, with Colombia and Peru receiving the largest numbers, followed by Ecuador and Chile, and more recently by Brazil. Since 2015, governments have granted legal stay through the provision of over 5.1 million special, time-limited residence permits. These measures allowed Venezuelans to live and work legally and were initially conceived as rapid and flexible tools to manage large-scale displacement.

This moment reflects a broader trend in which core legal principles appear increasingly subordinated to power politics. Beyond questions of legality, it also raises deeper uncertainties about Venezuela’s political future and what leadership change might mean for the possibility of return for nearly 8 million Venezuelans displaced since around 2015.

However, the limitations of this interim solution have become increasingly visible. Access to temporary permits has grown more restrictive, with the enforcement of tighter eligibility requirements and the reintroduction of border controls. While these schemes have enabled a quick path to legal stay for many Venezuelans, their temporary and conditional nature offer limited certainty about long-term protection or settlement. This policy choice is particularly striking in Latin America, where many states have deliberately incorporated the Cartagena definition into their national frameworks. This regional standard broadens refugee protection to include people fleeing widespread violence, human rights violations and serious public disorder. Under this definition, a significant share of Venezuelans could, in principle, be recognised as refugees, accessing a stronger, rights-based form of protection with greater legal certainty over time in host countries.

Nevertheless, my ongoing doctoral research at the University of Oxford with Venezuelans in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador, points to a clear pattern: many Venezuelans prefer temporary permits, despite their precarious and uncertain nature, over seeking refugee status, which is a protracted and complicated process. Temporary permits are comparatively simple and predictable – even when they involve fees.

But as the political environment shifts, broader questions are likely to arise about the sustainability of temporary permits and about what may come next for the more than 5 million Venezuelans currently living under them.

Will displaced Venezuelans return to Venezuela?

Comparative experience from other displacement contexts, such as Syria, suggests that even significant political or economic shifts in countries of origin do not automatically translate into large-scale return.

For many displaced Venezuelans, recent events symbolise the end of a political era marked with widespread human rights violations, the erosion of the rule of law, and large-scale displacement. These perceptions matter: they shape expectations about the future, influence personal and family decisions, and frame narratives around the possibility of return, even in the absence of immediate material change.

However, while the changing political situation may shape displacement dynamics, return is unlikely to be immediate or uniform.

Comparative experience from other displacement contexts, such as Syria, suggests that even significant political or economic shifts in countries of origin do not automatically translate into large-scale return. International standards make clear that return must be voluntary, safe and dignified, and premised on effective guarantees of physical security, legal protection, access to livelihoods, and institutional stability. In the absence of these conditions, and drawing on comparative experience from other protracted displacement contexts, any return is likely to remain limited and selective rather than widespread.

What may come next for displaced Venezuelans

After more than a decade spent managing Venezuelan arrivals, the question for host countries is no longer how to extend short-term legal stay, but whether this model can meaningfully evolve, or whether a different approach is needed. For most Venezuelans, medium-to long-term stay in host countries across the region therefore continues to be the more realistic horizon. This evolving situation points to three likely scenarios:

- Temporary protection as the dominant response: Temporary permits may continue to define access to legal stay across Latin America, operating largely at governments’ discretion, while refugee protection plays an increasingly limited role. As country-of-origin assessments evolve, this may affect future asylum decisions and, in some cases, the review of existing refugee status under international refugee law.

- Tighter access to legal stay and rising irregularity: Temporary permit schemes could be adjusted, affecting eligibility, duration, and in some cases their continuation. Given their discretionary nature, such shifts could increase legal uncertainty and, over time, push more Venezuelans into irregular status and onward movement.

- Selective return alongside sustained mobility: Voluntary return is likely to remain limited rather than widespread, shaped by continued uncertainty in Venezuela and occurring alongside ongoing mobility, including new departures by groups that had previously stayed in the country, some of whom supported Nicolás Maduro.

The bigger picture

The future of protection for Venezuelans will be shaped both by events in Venezuela and by political and electoral shifts in host countries. Electoral cycles and shifting domestic agendas in countries such as Ecuador, Chile and Peru are likely to influence whether existing legal protections are maintained, progressively narrowed, or increasingly reoriented towards return-focused approaches.

The future of protection for Venezuelans will be shaped both by events in Venezuela and by political and electoral shifts in host countries. Electoral cycles and shifting domestic agendas in countries such as Ecuador, Chile and Peru are likely to influence whether existing legal protections are maintained, progressively narrowed, or increasingly reoriented towards return-focused approaches.

Beyond Venezuela, these dynamics carry broader significance. The Latin American response, marked by the large-scale use of temporary permits and a more limited reliance on refugee protection, offers a revealing case of how states manage protracted displacement with precarious tools and under political uncertainty.

What happens next will affect not only the future of Venezuelans, but also how large-scale displacement is managed in other regional and global contexts, with consequences for society as a whole.

Dr Emily Warner, from Oxford University’s Nature-based Solutions Initiative, discusses the challenges of measuring biodiversity and capturing its complexity. She introduces a new framework aiming to simplify this process for practitioners, which was developed in collaboration with Dr Licida Giuliani and Dr Grant Campbell from the University of Aberdeen as part of an Agile Sprint on scaling up nature-based solutions in the UK.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Across the UK, abundance of all species has declined by an average of 19% since 1970 and nearly one in six species are at risk of extinction. The July 2025 assessment of progress on the Environmental Improvement Plan highlights the many habitat-based measures being implemented to tackle UK biodiversity loss, from four new National Nature Reserves to planting over 5,500 has of new woodland in England.

To understand whether these efforts are supporting progress towards the apex goal of thriving plants and wildlife, we need to assess how biodiversity is responding. Thinking about how we monitor these changes might seem boring, but it is important, and we won’t solve the biodiversity crisis without it!

Dr Emily Warner

Dr Emily WarnerWhy measuring biodiversity is so hard

From an increasing interest in biodiversity credits to national and international commitments to reverse biodiversity loss, the need for effective biodiversity monitoring methods is clear.

The challenge is that measuring biodiversity is notoriously complex. The Convention on Biological Diversity’s definition of biodiversity highlights how expansive a concept biodiversity is: 'the variability among living organisms from all sources and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems'.

With an increasing need to demonstrate success from conservation projects, the question of how to measure biodiversity is increasingly at the forefront of practitioners’ minds.

For example, nature-based solutions projects, which work with nature to tackle societal challenges, such as restoring a wetland to mitigate flooding, must also deliver benefits for biodiversity at their core. Similarly, multiple biodiversity credit systems – which allow the trading of tokens representing improved biodiversity – are in development in the UK alone, emphasising the critical need to be able to document increasing biodiversity.

With the rush to come up with a simple, tractable method of measuring biodiversity there is a simultaneous risk of oversimplifying, and we need to ask whether measuring something inadequately could be worse than not measuring it at all.

UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

For example, biodiversity net gain in the UK aims to ensure any habitat lost during development is replaced by more or better quality habitat. Biodiversity units are estimated based on habitat size, quality, location, and type, however, this approach overlooks many habitat attributes crucial to invertebrates, running the risk that invertebrate biodiversity will not be protected. UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach. It is perhaps unrealistic to expect to reduce biodiversity down to a single measurable variable, without acknowledging that doing so will inevitably lose a huge amount of information on changes in biodiversity.

A better way to measure what matters

To measure something diverse and complex we need to accept that the monitoring approach should reflect that diversity and complexity, while balancing this with feasibility. One way to increase the measurability of biodiversity is to structure the concept, breaking it down into component parts.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach.

In 1990, conservation biologist Reed Noss developed a hierarchical framework, organising biodiversity into three axes: composition, structure, and function, which can be assessed at four scales (genetic, population, community, landscape). If each axis represents a different aspect of biodiversity, then measuring metrics across the different axes should more widely capture biodiversity.

However, for each axis there are still many possible metrics that can be measured. Returning practitioners - or anyone else who wants to measure biodiversity - back to their original predicament of selecting the best metrics to effectively assess biodiversity.

Our recent research developed an ecological monitoring framework for nature-based solutions projects, seeking to overcome this problem.

We reviewed 71 possible biodiversity metrics, ranking them based on how informative they are and how feasible they are to measure. Of these, 30 metrics scored highly enough on both informativeness and feasibility to enter our framework. These metrics were grouped into Tier 1, Tier 2, and Future metrics.

Tier 1 are the highest priority metrics in terms of informativeness and represent all three axes of biodiversity. Future metrics are equally informative but currently too technically challenging or costly to measure. Tier 2 metrics are informative but often less widely applicable than Tier 1 metrics.

These metrics are now freely available in a searchable database, allowing practitioners to identify suitable metrics for their projects based on criteria such as cost, technical expertise required, and availability of a standardised methodology for data collection.

As assessing biodiversity requires investment of time, expertise, and money, we want its results to be as impactful as possible.

Our database will channel the energy put into biodiversity monitoring towards cohesive, effective data collection, that widely captures change across the complexity of biodiversity, encouraging measurement of the different axes and scales of biodiversity.

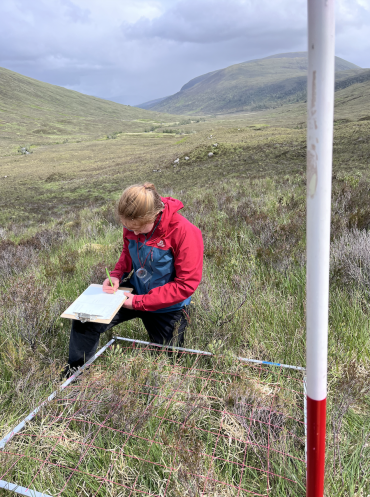

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

We hope our database will help to navigate the huge pool of possible biodiversity metrics, highlighting the most useful metrics for assessing biodiversity and giving a clearer understanding of what information they provide.

The next step in any biodiversity monitoring plan is then getting out and collecting the data, ideally in a standardised way that will allow comparison between projects or to existing datasets.

The 'how' of biodiversity monitoring unmasks another layer of complexity, as for most of the metrics in the database there are multiple potential methods for data collection and decisions need to be made about a sampling plan. In some cases, there are even different ways of calculating the final metric.

A large part of the research underpinning the development of our metrics database involved identifying existing standardised methodologies that could be used to collect data.

The increased interest in monitoring biodiversity could lead to a boom in biodiversity data, representing a huge opportunity to better understand the trajectory of biodiversity across a wider range of UK contexts, but also the potential risk of a missed opportunity to maximise the outcomes of this data collection effort.

By helping make these standardised metrics and methodologies available, we hope to encourage coordinated, large-scale biodiversity data collection to support effective biodiversity action and also highlight where more guidance is needed to support data collection on the ground.

Effective monitoring to turn the tide on biodiversity loss

Our monitoring tool aims to provide shortcuts to developing a monitoring approach, highlighting what different metrics tell us about biodiversity, connecting these to available methods and allowing practitioners to search these metrics based on key criteria.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

We have been aware that biodiversity has been declining since before I was born and this continues to escalate. My hope is that I will see the transition to a positive trend in biodiversity over the rest of my career and that this monitoring tool could be one small step on this pathway.

As Oxford’s new academic year gets underway, we take a closer look at an award-winning teaching module that brings students face-to-face with real-world high-stakes decisions.

What would you do if there was a sudden nuclear threat from North Korea and you were responsible for deciding how your country responded? At Oxford University’s Blavatnik School of Government, Master of Public Policy (MPP) students tackle this challenge head-on in the 'North Korea Crisis Simulation' – an immersive teaching module that represents an innovative approach to teaching public policy.

The one-year postgraduate degree is designed to equip future leaders with practical skills for public policy practice. Its students come from around the world – last year hailing from 58 different countries and diverse backgrounds such as government, NGOs, journalism and academia.

The simulation, which was recognised earlier this year by the Vice-Chancellor’s ‘Innovative Teaching and Assessment’ Award, plunges the MPP students into a complex economic, political, and military crisis on the Korean peninsula; testing their ability to make high-stakes decisions, balance national priorities, manage security concerns, and collaborate with international partners under extreme pressure – all within a world marked by interconnected crises and rising geopolitical competition.

Students assigned to the DPRK (North Korea) room developing strategy

Students assigned to the DPRK (North Korea) room developing strategyThe simulation is the brainchild of Professor Tom Simpson, who has first-hand experience of complex military situations, having served as an officer with the Royal Marine Commandos for five years. It incorporates elements of a ‘war game’, imitating a geopolitical crisis scenario where participants’ actions impact the options available to others.

This simulation challenges students to integrate theoretical knowledge with practical skills, pushing them to perform under high-stakes conditions.

It provides a deeply immersive experience that evolves based on their decisions, enhancing their understanding of national power dynamics. So our students are gaining invaluable insights into real-world policymaking and developing skills directly applicable to their future careers.

Professor Tom Simpson, Blavatnik School of Government

Split into six teams or countries – USA, China, Japan, Russia, South Korea, and North Korea – the students operate from meticulously designed ‘situation rooms’ complete with national flags, authentic snacks, and tailored props such as national seals on stationery, badges, and door plaques, as well as portraits of national leaders. The rooms are equipped with a bespoke communications suite, giving students the ability to receive recordings and live broadcasts from the dedicated Green Room.

In the weeks leading up to the simulation, MPP students receive detailed background briefings and in-depth reading assignments and research into the history of the crisis, the political, economic, and cultural characteristics of the countries in the region, and the national interests of the six countries involved. But it’s not until 24 hours before the exercise itself begins, when they are presented with confidential instructions, that they learn what their individual roles in the simulation will be. And then, at the start of the simulation, they finally learn about the crisis that is unfolding.

Aoife, a student from Northern Ireland who was assigned the role of the Chief of Staff to the President of the USA said: ‘I got to be a decision-maker at the epicentre of the simulation, which taught me a lot about teamwork, how to handle pressure, and the importance of maintaining focus on your ultimate goal.’

She also reflected on the challenges of working collaboratively in such a pressured environment: ‘It was really eye-opening to be thrown into a scenario where you have only limited information, there’s mistrust across teams, but the stakes are so high that you know you have to find a way of working together.’

Students participating in the breaking news broadcast that concludes the simulation

Students participating in the breaking news broadcast that concludes the simulationWhile fictional, events in the simulation closely resemble real-world occurrences, such as the abduction of Japanese citizens by North Korea, financial turbulence, and gunfire in the Demilitarised Zone, to emphasise the complexities of real-world decision-making.

Erik, a Ukrainian MPP student, reflected: ‘The most valuable lessons were about teamwork under immense time pressure and responsibility; organising team efforts, balancing each member's involvement with the need to make quick decisions, effectively delegating tasks, and strategic action planning. I learned the importance of being ready to pursue moderate goals, as aiming for maximalist objectives can lead to counterproductive results.’

The award-winning ‘North Korea Crisis Simulation’ is one example of an immersive teaching method that has long been championed by the Blavatnik School’s Case Centre on Public Leadership, which develops teaching materials for public leaders at all career stages, thrusting them into the heart of a range of crises and challenges around the globe. The North Korea Crisis Simulation module has been made freely available for other schools of public policy to download here.

Professor Mark Graham

Professor Mark GrahamWithout data annotators creating datasets that can teach AI the difference between a traffic light and a street sign, autonomous vehicles would not be allowed on our roads. And without workers training machine learning algorithms, we would not have AI tools such as ChatGPT.

Professor Mark Graham researches global technology through the eyes of the hidden human workforce who produce it. He argues that AI is an "extraction machine", churning through ever-larger datasets and feeding off humanity’s labour and collective intelligence to power its algorithms.

We caught up with Mark to discuss some of these issues.

In talking about the AI technologies we rely on, you mention the "countless humans forced to work like robots, toiling in monotonous low-paid jobs just to make such remarkable machines possible" -- who are these people, and what sorts of jobs are they doing?

There is a whole range of ‘data work’ needed to make our digital lives possible. Data annotators label data with tags so that it can be understood by computer programs. Content moderators sift through digital content in order to remove harmful content that breaches company guidelines. If you have ever interacted with any form of AI, whether it be a chatbot, a search engine, a social media feed, a streaming recommendation system, or a facial recognition system, data workers have had a hand in building or maintaining those systems.

The root cause of the problems encountered by data workers lies in the power imbalance between them and the institutions that govern their jobs… It is unlikely that any of the issues data workers experience will ever be meaningfully addressed without workers building their collective power in movements and institutions.

You talk about "building worker power", as a step towards redressing some of the issues of the hidden labour of AI — I guess this is quite difficult when these jobs are so atomised, and the workforce so expendable?

The root cause of the problems encountered by data workers lies in the power imbalance between them and the institutions that govern their jobs. Historically, when social movements achieve lasting change, it's often through organizing a critical mass of people to push for policies that address systemic inequalities. It is therefore unlikely that any of the issues data workers experience will ever be meaningfully addressed without workers building their collective power in movements and institutions.

However, data workers face serious barriers to ever building that power. The jobs that they undertake are relatively footloose and standardised, and, as a result, are carried out in a planetary-scale labour market. Their jobs can be quickly shifted to the other side of the planet.

There are no easy ways for workers to build collective power under these sorts of conditions. Data workers in a country like Kenya or the Philippines have an enormous structural disadvantage. However, that is not to say that organizing is impossible. In production networks that are organised globally, workers will increasingly also need to explore ways of organising across geographies. This will undoubtedly take a range of forms, but will all need to be rooted in the principle that workers acting collectively will be able to demand better conditions for everyone in a production network. Isolated efforts, by contrast, are unlikely to achieve lasting change.

A requirement of accountability is visibility. What are some of the ways that this labour is hidden from us -- and why? How could it be made more open and visible, more recognised?

The labour in AI production networks is almost always hidden from view. If you drink a cup of coffee or buy a pair of shoes, you probably have a conception that at some point that coffee passed through the hands of a plantation worker or the shoes were assembled by someone in a sweatshop. However, precisely because AI presents itself as automated, very few people can imagine what the human labour on the other side of the screen looks like. AI companies are complicit in this subterfuge. They want to present themselves as technological innovators rather than as the firms behind vast digital sweatshops.

Because AI presents itself as automated, very few people can imagine what the human labour on the other side of the screen looks like. AI companies are complicit in this subterfuge.

Because of this enormous gap between how tech companies present themselves and the actual on-the-ground conditions experienced by workers in those production networks, I started the Fairwork project. Fairwork evaluates companies against principles of decent work and gives every company a score out of 10 based on how well they stack up against those principles. To date, we have scored almost 700 companies in 38 countries. Doing this work has encouraged a lot of companies to make improvements to the working conditions of their workers to receive a higher score.

The next phase of our project will involve going to the lead firms in AI production networks, the brands that consumers are familiar with, and letting them know that we are going to start holding them accountable for all the working conditions upstream in their production networks. We will constructively work with them to embed principles of fair work into their contracts and supplier agreements, but also use our research to hold them accountable when they fail to do so.

Watch Mark’s latest video highlighting the hidden cost of AI and the implications of this ever-evolving technology for the thousands of AI workers toiling away behind the scenes to deliver AI powered services.

I guess an obvious solution to some of these issues is regulation -- workers should be protected in whatever jurisdiction they are working, and wherever in the production chain they sit. What efforts are being made in this area?

The planetary labour market that much of this work is traded in makes it difficult for regulators in the Global South to raise conditions. If regulation raises costs in Kenya, those jobs can move to India. If regulation in India raises costs, those jobs can move to the Philippines. These dynamics create a ‘race to the bottom’ in wages and working conditions, leaving regulators having to choose between bad jobs or no jobs. As the economist Joan Robinson famously said, ‘The misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.'

However, even though the global geography of the labour market neuters the ability of regulators to act in the Global South, it strengthens the hand of regulators in the Global North. Regulators in countries that are home to a lot of the demand for digital products and services have the ability to play an outsized role in setting standards. The EU's proposed Supply Chain Directive is a good example of this. It aims to make companies operating in the EU accountable for human rights and environmental impacts throughout their global supply chains. Because few AI companies will want to forgo being able to sell to consumers in the EU, this directive has the potential to improve conditions for the many workers in countries with weak labour protections.

Much of the discussion about AI has been focused on existential risks that it might present in the medium- to long-term future. However, the real risks of AI are already right here in the present.

Finally, your assessment of the AI industry is pretty bleak, that "workers are treated as little more than the fuel needed to keep the machine running" — and that this is happening to all of us, right now. What are some of the key issues and battlegrounds in which this question will be played out in the coming years?

Much of the discussion about AI has been focused on existential risks that it might present in the medium- to long-term future. However, the real risks of AI are already right here in the present.

A few decades ago, anti-sweatshop campaigns shifted attention to the plight of garment workers, and shifted the onus of responsibility for those workers onto the brands who sell clothes. Those campaigns did not fully eradicate sweatshops, but have been an important moment on a path to normalising the idea that lead firms in production networks have the potential power to impose decent work conditions throughout a supply chain. If we are to head towards a fairer future of work, one of the key battlegrounds will have to be ensuring that big tech companies take responsibility for the conditions of all workers in their supply chains.

Because tech companies have, to date, taken on very little of this responsibility, pressure will be required from consumers, policy makers, and workers. Consumers will have to recognise that they are complicit in the conditions of workers who made or maintained the product or service that they are using. Policy makers will have to realise that a laissez-faire approach to regulation is only serving to increase inequalities. And workers will have to find ever more creative ways to organise across supply chains in order to hold companies accountable. Until we all force these companies to change, we will only continue to be nothing more than fuel for the machine.

***

Professor Mark Graham was talking to the OII's Scientific Writer, David Sutcliffe.

Mark Graham is Professor of Internet Geography at the Oxford Internet Institute, where he leads a range of research projects spanning topics between digital labour, the gig economy, internet geographies, and ICTs and development. He's also the Prinicipal Investigator of the participatory action research project Fairwork, which aims to set minimum fair work standards for the gig economy.

Read his latest book: James Muldoon, Mark Graham, and Callum Cant (2024) Feeding the Machine. Canongate.

Astrophoria’s Programme Director, Dr Jo Begbie, speaks about the programme’s first year and shares her highlights.

As the end of the academic year fast approaches, twenty-two students from across the UK will soon be completing the University’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year. Providing a one-year fully funded course for UK state school students who have experienced severe personal disadvantage or disruption to their education, the Astrophoria programme is designed to enable motivated students to reach their academic potential by bridging the gap between A-Levels and Oxford’s challenging undergraduate degrees.

It is led by Dr Jo Begbie, who has had plenty of experience of educational environments prior to arriving in Oxford in 2004: completing her undergraduate degree at Leeds, a PhD at UCL, and postdoctoral research at King’s College, London. At Oxford, Jo started a research lab and took up the post of lecturer in Medicine, before becoming a Tutor in Medicine at one of Oxford’s colleges, Lady Margaret Hall.

Students meet Oxford's Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey and Astrophoria Director, Jo Begbie, during their orientation week

Students meet Oxford's Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey and Astrophoria Director, Jo Begbie, during their orientation week“And then as a medicine tutor doing admissions, I could see that there were students that had potential but weren’t going to get the grades to come into Oxford, and often they were young people from less advantaged backgrounds – Astrophoria is about putting those two things together.”

Foundation Years can mean different things for different institutions, says Jo. At Oxford, the Astrophoria programme – which follows on from a college-based initiative Jo was involved in at Lady Margaret Hall – provides lower contextualised offers for entry to study. But importantly, according to Jo, “rather than lowering grades for undergraduate study and expecting them to cope”, it gives the students a year of support, both academic and personal (there is a dedicated welfare role in the team), before they join the undergraduate student body.

Over the course of the academic year, students not only receive teaching in their chosen subject (in Humanities, Law, PPE, or CEMS (Chemistry, Engineering, and Material Science) ), they also undertake a Preparation for Undergraduate Studies course. “It’s thinking about what academic skills they might require and recognising they may need support in order to thrive on an undergraduate course,” Jo says, “but also helping them build that sense of belonging in an academic institution like Oxford, which has its own nuances and distinct learning environment and can be quite a big step for some students.”

Chemistry student Yihao during his first term as an Astrophoria student at Oxford

Chemistry student Yihao during his first term as an Astrophoria student at OxfordThe first Astrophoria students arrived last September for their Orientation Week, which, Jo says, was “really important for building that sense of belonging and starting to do some critical thinking, but in a slightly more playful way. It’s quite deliberately set up to get them to be engaged in asking questions and starting to build their confidence.”

The students are based across 9 Oxford colleges, coming together for different aspects of the course and events. So how well have the cohort integrated into the wider student body? “We were a bit nervous about that” says Jo, “but, it hasn’t been an issue – they’ve been embraced by their colleges and just treated like any other student”.

A dedicated Outreach Officer in Jo’s team visits schools to build awareness of the Astrophoria programme among teachers and students. The reaction is overwhelmingly positive: “There’s quite often – more from the teachers – ‘oh, this really is as good as it sounds’”.

The team are focused on ensuring that eligible applicants feel motivated to apply. “There are still some students who think that Oxford’s not going to be for them, but it’s nice to begin to build our cohort of students who’ve been through the programme, to be able to use their voices to go back to schools so that they can try and dispel some myths about who Oxford is for.”

Astrophoria students speak about their experiences at an event in Oxford

Astrophoria students speak about their experiences at an event in OxfordReflecting on the programme’s inaugural year, Jo’s personal highlights come from the students and how they’ve developed, which she has seen first-hand through teaching as part of the Preparation for Undergraduate Study courses. “Some students in the first term are very nervous, very shy, very unsure and they’ve just grown in confidence and engagement in talking about things.”

A recent assessment in which the students presented posters addressing an academic question was a particular high point: “For me, the energy just really summed up the Astrophoria year. There were 22 students talking animatedly about an academic topic they were interested in, and they were energised but also supportive of each other and explaining their work to one another. Essentially that’s what we’ve been trying to build – we talk about a community and support network, an excitement in the academic work that they’re doing, and a willingness to present things."

Another ‘proud mum’ moment, as she calls them, came at an event with the Astrophoria donor. “Two of the students gave speeches and you just felt ‘wow’. They'd only been here a term but were happy to stand up and speak at an event”.

Have there been any surprises this year? Nothing major, she says, but “dealing with 22 young people there’s always something!”. Inevitably, says Jo, the programme will evolve as lessons are learnt, and the goal is to steadily increase the number of Astrophoria students over the next few years. Some of this year’s cohort may not progress on to Oxford’s undergraduate courses, but Jo hopes they have all benefitted from the programme and their Oxford experience; “I want the students to feel empowered”, she says.

Find out more about the Astrophoria Foundation Year.

- 1 of 9

- next ›

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools