How do we measure success in the fight to save nature?

Dr Emily Warner, from Oxford University’s Nature-based Solutions Initiative, discusses the challenges of measuring biodiversity and capturing its complexity. She introduces a new framework aiming to simplify this process for practitioners, which was developed in collaboration with Dr Licida Giuliani and Dr Grant Campbell from the University of Aberdeen as part of an Agile Sprint on scaling up nature-based solutions in the UK.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Biodiversity supports the very fundamentals of human life, but its multi-faceted nature means it is easy for aspects of it to be in decline without us even realising.

Across the UK, abundance of all species has declined by an average of 19% since 1970 and nearly one in six species are at risk of extinction. The July 2025 assessment of progress on the Environmental Improvement Plan highlights the many habitat-based measures being implemented to tackle UK biodiversity loss, from four new National Nature Reserves to planting over 5,500 has of new woodland in England.

To understand whether these efforts are supporting progress towards the apex goal of thriving plants and wildlife, we need to assess how biodiversity is responding. Thinking about how we monitor these changes might seem boring, but it is important, and we won’t solve the biodiversity crisis without it!

Dr Emily Warner

Dr Emily WarnerWhy measuring biodiversity is so hard

From an increasing interest in biodiversity credits to national and international commitments to reverse biodiversity loss, the need for effective biodiversity monitoring methods is clear.

The challenge is that measuring biodiversity is notoriously complex. The Convention on Biological Diversity’s definition of biodiversity highlights how expansive a concept biodiversity is: 'the variability among living organisms from all sources and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species, and of ecosystems'.

With an increasing need to demonstrate success from conservation projects, the question of how to measure biodiversity is increasingly at the forefront of practitioners’ minds.

For example, nature-based solutions projects, which work with nature to tackle societal challenges, such as restoring a wetland to mitigate flooding, must also deliver benefits for biodiversity at their core. Similarly, multiple biodiversity credit systems – which allow the trading of tokens representing improved biodiversity – are in development in the UK alone, emphasising the critical need to be able to document increasing biodiversity.

With the rush to come up with a simple, tractable method of measuring biodiversity there is a simultaneous risk of oversimplifying, and we need to ask whether measuring something inadequately could be worse than not measuring it at all.

UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

For example, biodiversity net gain in the UK aims to ensure any habitat lost during development is replaced by more or better quality habitat. Biodiversity units are estimated based on habitat size, quality, location, and type, however, this approach overlooks many habitat attributes crucial to invertebrates, running the risk that invertebrate biodiversity will not be protected. UK invertebrates are declining faster than plants and birds, threatening the foundation of ecosystems and direct benefits they provide to humans, such as food security, which is underpinned by pollination and pest control.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach. It is perhaps unrealistic to expect to reduce biodiversity down to a single measurable variable, without acknowledging that doing so will inevitably lose a huge amount of information on changes in biodiversity.

A better way to measure what matters

To measure something diverse and complex we need to accept that the monitoring approach should reflect that diversity and complexity, while balancing this with feasibility. One way to increase the measurability of biodiversity is to structure the concept, breaking it down into component parts.

In contrast to monitoring carbon sequestration associated with conservation projects, where the focal unit of measurement – a tonne of carbon – is unequivocally defined, biodiversity’s complexity requires a much more nuanced approach.

In 1990, conservation biologist Reed Noss developed a hierarchical framework, organising biodiversity into three axes: composition, structure, and function, which can be assessed at four scales (genetic, population, community, landscape). If each axis represents a different aspect of biodiversity, then measuring metrics across the different axes should more widely capture biodiversity.

However, for each axis there are still many possible metrics that can be measured. Returning practitioners - or anyone else who wants to measure biodiversity - back to their original predicament of selecting the best metrics to effectively assess biodiversity.

Our recent research developed an ecological monitoring framework for nature-based solutions projects, seeking to overcome this problem.

We reviewed 71 possible biodiversity metrics, ranking them based on how informative they are and how feasible they are to measure. Of these, 30 metrics scored highly enough on both informativeness and feasibility to enter our framework. These metrics were grouped into Tier 1, Tier 2, and Future metrics.

Tier 1 are the highest priority metrics in terms of informativeness and represent all three axes of biodiversity. Future metrics are equally informative but currently too technically challenging or costly to measure. Tier 2 metrics are informative but often less widely applicable than Tier 1 metrics.

These metrics are now freely available in a searchable database, allowing practitioners to identify suitable metrics for their projects based on criteria such as cost, technical expertise required, and availability of a standardised methodology for data collection.

As assessing biodiversity requires investment of time, expertise, and money, we want its results to be as impactful as possible.

Our database will channel the energy put into biodiversity monitoring towards cohesive, effective data collection, that widely captures change across the complexity of biodiversity, encouraging measurement of the different axes and scales of biodiversity.

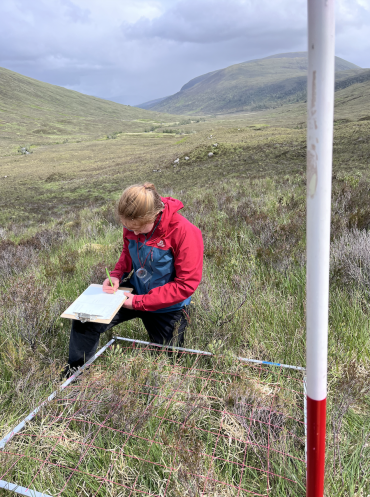

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

Dr Emily Warner measuring biodiversity in the field. Credit: Ella Browning

We hope our database will help to navigate the huge pool of possible biodiversity metrics, highlighting the most useful metrics for assessing biodiversity and giving a clearer understanding of what information they provide.

The next step in any biodiversity monitoring plan is then getting out and collecting the data, ideally in a standardised way that will allow comparison between projects or to existing datasets.

The 'how' of biodiversity monitoring unmasks another layer of complexity, as for most of the metrics in the database there are multiple potential methods for data collection and decisions need to be made about a sampling plan. In some cases, there are even different ways of calculating the final metric.

A large part of the research underpinning the development of our metrics database involved identifying existing standardised methodologies that could be used to collect data.

The increased interest in monitoring biodiversity could lead to a boom in biodiversity data, representing a huge opportunity to better understand the trajectory of biodiversity across a wider range of UK contexts, but also the potential risk of a missed opportunity to maximise the outcomes of this data collection effort.

By helping make these standardised metrics and methodologies available, we hope to encourage coordinated, large-scale biodiversity data collection to support effective biodiversity action and also highlight where more guidance is needed to support data collection on the ground.

Effective monitoring to turn the tide on biodiversity loss

Our monitoring tool aims to provide shortcuts to developing a monitoring approach, highlighting what different metrics tell us about biodiversity, connecting these to available methods and allowing practitioners to search these metrics based on key criteria.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

If we want to bend the curve of biodiversity loss we need effective monitoring to understand how well our efforts to restore nature are working.

We have been aware that biodiversity has been declining since before I was born and this continues to escalate. My hope is that I will see the transition to a positive trend in biodiversity over the rest of my career and that this monitoring tool could be one small step on this pathway.

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators