Features

Professor Kamaldeep Bhui of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry, and former Editor-in-Chief of the British Journal of Psychiatry, explains the importance of editorial independence in promoting good science.

Given the contested nature of much mental health and brain research, it has never been more important for research in this area to be of the highest quality and observing the principles of research integrity and publication ethics. In so doing we ensure the production of knowledge does not bias the findings towards compounding health inequalities, with adverse policy or practice impacts.

As a psychiatrist and former editor of a scientific journal, I believe that editorial independence, through robust practice of publication ethics and research integrity, promotes good science and prevents bad science.

When editorial independence is challenged, we should all be concerned. This is why, together with senior members of the editorial team, I wrote an editorial for the British Journal of Psychiatry, the journal for which I used to be Editor-in-Chief.

Editorial independence in journals can be defined as editors having the freedom to make decisions about the scientific publication record. To promote good science, editorial independence must be non-negotiable for all scientific journals seeking to prevent influence from their owners or from groups with vested interests.

However, editorial independence is a multidimensional, dynamic, and complex concept that is often constructed in our responses to new and emerging challenges.

In the editorial, I outlined that too much published research is unsound with up to 10% of large-scale randomised trials suffering from major flaws. Corrections and retractions are one solution and should not be stigmatised. Rather they should be an accepted part of the contract between authors and editors, and a wider group of stakeholders. All should work in trust to establish and correct the scientific record on which public policy and practice can improve.

Dealing with older papers is especially complex. Scientific knowledge is contextual. Dismissing ‘old’ research entirely based on modern standards may overlook their incremental contributions. However, older papers should be appraised and judged against best practice at the time of publication; if found to be flawed in some fundamental scientific way, removal from the scientific record is appropriate.

Poor studies remain in the scientific record. There are hardly any requests for correction or retraction of uninfluential or uncited papers. Therefore, there is often a pressure to not retract a paper which is contributing to controversy and debate, as it rather perversely raises the profile of a journal. Indeed, many retracted or unretracted discredited papers continue to be highly cited.

Some larger publishers take charge of complaints, potential retractions, and any legal threats rather than following the guidance on editorial independence. This risks vested non-scientific interests becoming the basis or appearing to be the basis for decisions about flawed science.

An alarming trend is the use of legal threat to strategically control the publication and dissemination of public scientific findings. Legal challenges to editorial independence are especially difficult as settlements can be costly. To avoid this risk, owners may choose to neglect editorial decisions and undermine editorial independence. Our wider duties must also consider standards in public life and our respective professional values and codes of conduct.

When there are complaints or allegations of error, it is critical that the editor and author discuss potential remedies, for example corrections, re-analysis, the reporting and interpretation of the findings. This step should precede any discussion of potential retraction. When retraction is necessary, this should be mutually agreed if possible. A mutually satisfactory decision to retract may not be possible if authors object, or worse, if they resort to legal threat, thereby blocking any meaningful dialogue about the validity of their research.

As a former Editor in Chief and researcher myself, I know that the most important quality-control mechanism for research integrity is editorial independence guided by publication ethics to ensure that there is an uncompromising insistence on meeting the highest standards of scientific research, reporting and publication. Only then can improvements in practice and policy be grounded in science rather than vested interests.

Compliance with best practice guidance varies. Therefore, in our editorial, we suggested how we could protect and strengthen editorial independence. For example, regulation could include a register of breaches and scrutiny to learn lessons, as well as provision for legal advice on issues of public interest. Compliance with guidance, and adequate insurance and transparency must accompany the reconciliation of ethical and legal dilemmas. Scientists might disagree, the public and organisations representing specific positions might disagree; but the whole health industry from researcher, policy maker, to journal owners and editors must ensure they are capable and competent to fulfil obligations to protect editorial independence. Mapping policy and practice impacts of breaches, transparent processes for noting legal threats, and ethical leadership must sit alongside robust governance to support publication ethics and the principles and guidance on editorial independence.

Our early experiences can have a staggering impact on the rest of our lives – for better or worse. For young girls forced into marriages or unions against their will, usually with adult men, this can have profound lifelong consequences, including for wellbeing, education, and employment opportunities. Reducing early marriage can take many years of culture change, societal pressure, and policy change to transform the situation.

This is a strong example of how really robust, high-quality longitudinal research combining both quantitative and qualitative data can directly influence national policies to improve the lives of children and young people.

Dr Alan Sanchez, Young Lives Senior Quantitative Researcher

But along this journey, there are often turning points: pivotal moments that propel future progress.

In Peru, such a moment came on 25 November 2023 when the Government introduced new legislation to prohibit all marriages with minors under the age of 18. The potential impacts of this cannot be overstated: between 2013 and 2022, over 4,350 child marriages involving girls between the ages of 11 and 17 years were registered. Almost all (98%) of these resulted in young girls being married to adult men. But this is likely only the tip of the iceberg: estimates based on census data indicate that over 56,000 children aged between 12 and 17 (mostly girls) may be involved in a union and/or cohabitation.

This new law has closed a previous legal loophole which permitted teenagers to be married from the age of 14 years under certain conditions, with consent from at least one parent, despite the minimum legal age of marriage of 18 years for both girls and boys. Not only does the new law close this loophole, it also enables girls who were married as minors to have their marriages annulled.

On the surface, this may seem simply like a formal legislative process, but behind the scenes are years of evidence-gathering, lobbying, and policy engagement. In particular, the Young Lives study coordinated by the University of Oxford played a transformative role in building a compelling evidence base to champion the need for change.

Data that fills in the gaps

In combination, the Young Lives data fills in a key evidence gap by giving a personal glimpse into what early marriage is actually like in these countries. Beyond the high-level statistics, there are personal stories that resonate.

Julia Tilford, Communications Manager for Young Lives

‘It is rare that you can draw a direct link between academic research and policy change, but in this case, it is unequivocal’ says Julia Tilford, Communications Manager for Young Lives. Since 2001, the project has been following the lives of 12,000 young people in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam, using a combination of surveys (conducted every 3 to 4 years) and supplementary in-depth interviews to generate high-quality, large-scale longitudinal data on the causes and consequences of poverty and inequality. From 2005, Young Lives has been led by the Department of International Development at the University of Oxford. However, Young Lives also works in collaboration with key partners in each of the four study countries, who are engaged directly with national policy and programme decision-makers – those in a position to effect change. Young Lives has also worked with Child Frontiers to conduct in-depth interviews on the lived experience of early and child marriage and parenthood in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Zambia.

Understanding the long-term impacts of early marriage for children and young people in poor communities is one of many aspects the study has holistically examined. It has demonstrated that girls who marry early are less likely to complete secondary education, leading to reduced opportunities to gain employment and financial independence. Girls from poor households and rural areas typically have limited knowledge about or access to sexual and reproductive health care and services, increasing the risk of teenage pregnancies. Furthermore, children born to young mothers (under the age of 18) generally have a lower birthweight and shorter height for their age. Girls who marry early are also at much greater risk of physical and psychosocial violence from their partners.

Some of the harmful impacts that marrying young can have on girls. Source: Young Lives.

Some of the harmful impacts that marrying young can have on girls. Source: Young Lives. Every year, at least 12 million girls are married before they reach the age of 18. That is 28 girls every minute (UNICEF).

Translating research to policy impact

Leading up to the new Parliamentary Bill, Young Lives’ Peru team presented evidence on the impacts of early marriage and cohabitation through numerous presentations and briefings to key government officials, including in the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations and the Ministry of Education. When the bill was presented to Congress in September 2022, Young Lives evidence was directly cited by Congresswoman Flor Pablo, who then invited Young Lives team members to present their findings at an influential congressional roundtable.

Being on the ground for over twenty years has enabled our Country Directors to establish long-term partnerships of trust and collaboration with key government partners and policy decision-makers. This enables Young Lives to be very effective at influencing national policies and programmes.

Kath Ford, Senior Policy Officer for Young Lives.

Dr Alan Sanchez, Young Lives Senior Quantitative Researcher and part of the group who presented at the roundtable, says: ‘Having such a robust evidence base was critical, because many people in Peru didn’t actually believe that early marriage had negative consequences.’

Alongside engaging with policy makers, Young Lives has also communicated its findings more widely – developing an animation, and working with the national press, which led to the findings being cited in high-profile articles in El Comercio and La República. The momentum built by these actions proved critical to keep the bill in progress when a political storm unleashed following the Peruvian President’s removal in December 2022 after an attempted coup d’état. Although the debate was postponed because of this, the bill eventually passed with 97% of Congress in favour.

‘What I have learnt from this process is that change takes time’ adds Dr Sanchez. ‘Besides the years needed to build up our strong longitudinal evidence base, it also takes time to analyse the data and build up support in Congress. You also need teamwork and political allies. In this case, having the support of Congresswoman Pablo was pivotal. She was personally motivated to change the law, and championed our evidence with key government ministers. In the end, even those who were political adversaries agreed that the bill was needed.’

Looking Forward

‘While the change in Peru’s legislation is an incredibly important step in protecting young girls from child marriage, legislation alone is not enough’ says Kath Ford, Senior Policy Officer for Young Lives. ‘The Young Lives study shows that poverty, gender inequality, and discrimination are key drivers of child marriage, meaning that policymakers need to adopt a broad approach to deliver real change for girls and young women. Tackling the root causes of child marriage also involves working closely with whole communities, including men and boys, and ensuring vulnerable girls and young women are protected by effective safety nets.’

Young Lives longitudinal evidence on the causes and consequences of child marriage in Peru has been pivotal for driving this important legislative change. By giving voice to the lived experiences of girls and young women, the study has enabled a much more in-depth understanding of how poverty and entrenched gender norms continue to drive child marriage, particularly among remote and indigenous communities.

Congresswoman Flor Pablo

Young Lives evidence on the consequences of early marriage is also starting to have a significant impact in India, where nearly 1 in 4 young women are married before the age of 18 (UNICEF, 2022). The Young Lives India team were invited to present evidence to the Indian Parliamentary Standing Committee as part of their examinations of a proposed new bill to increase the legal age of marriage for women from 18 to 21 years of age. This would be a seismic policy shift for a country where the majority of young women currently get married between the ages of 18 and 21.

Dr Renu Singh, Country Director, Young Lives India, says: ‘Young Lives has raised the importance of curbing child marriage and brought this important issue to the attention of policy makers over a number of years. The fact that the bill to raise the marriage of girls from 18 to 21 years has been passed by Cabinet, the first critical legislative step, before being ratified by Parliament is testament to this ongoing pressure.'

Meanwhile, the Young Lives team in Oxford are now completing the latest round of survey interviews. With the respondents now aged 22 and 29, the study is now focusing on how they are faring in young adulthood across a broad range of areas, including physical and mental health, education, work, and family relationships. New research findings will be published in early 2025.

You can learn more about Young Lives on the project's website.

A young mother and her children in India. © Young Lives / Sarika Gulati

A young mother and her children in India. © Young Lives / Sarika GulatiBrian Christian is an acclaimed American author and researcher who explores the human and societal implications of computer science. His bestselling books include ‘The Most Human Human’ (2011), ‘Algorithms to Live By’ (2016), and ‘The Alignment Problem’ (2021), the latter of which The New York Times said ‘If you’re going to read one book on artificial intelligence, this is the one.’ He holds a degree from Brown University in computer science and philosophy and an MFA in poetry from the University of Washington.

Here, Brian talks about the latest chapter of his career journey: starting a DPhil (PhD) at the University of Oxford to grapple with the challenge of designing AI programs that truly align with human values.

Brian at the entrance of Lincoln College, Oxford. Credit: Rose Linke.

Brian at the entrance of Lincoln College, Oxford. Credit: Rose Linke.

One of the fun things about being an author is that you get to have an existential crisis every time you finish a book. When The Alignment Problem was published in 2021, I found myself ‘unemployed’ again, wondering what my next project would be. But writing The Alignment Problem had left me with a sense of unfinished business. As with all my books, the process of researching it had been driven by a curiosity that doesn’t stop when it reaches the frontiers of knowledge: what began as scholarly and journalistic questions simply turned into research questions. I wanted be able to go deeper into some of those questions than a lay reader would necessarily be interested in.

The Alignment Problem is widely said to be one of the best books about artificial intelligence. How would you summarise the central idea of the book?

The alignment problem is essentially about how we get machines to behave in accordance with human norms and human values. We are moving from traditional software, where behaviour is manually and explicitly specified, to machine learning systems that essentially learn by examples. How can we be sure that they are learning the right things from the right examples, and that they will go on to actually behave in the way that we want and expect?

This is a problem which is getting increasingly urgent, as not only are these models becoming more and more capable, but they are also being more and more widely deployed throughout many different levels of society. The book charts the history of the field, explains its core ideas, and traces its many open problems through personal stories of about a hundred individual researchers.

Most AI systems are built on the assumption that humans are essentially rational but we all act on impulse and emotionally at times. However, there is currently no real way of accounting for this in the algorithms underpinning AI.

So, how does this relate to your DPhil project?

Under the supervision of Professor Chris Summerfield in the Human Information Processing lab (part of the Department of Experimental Psychology), I am exploring how cognitive science and computational neuroscience can help us to develop mathematical models that capture what humans actually value and care about. Ultimately, these could help enable AI systems that are more aligned with humans – and which could even give us a deeper understanding of ourselves.

For instance, most AI systems are built on the assumption that humans are essentially rational utility maximisers. But we know this isn’t the case, as demonstrated by, for instance, compulsive and addictive behaviours. We all act on impulse and emotionally at times - that’s why they put chocolate bars by the checkouts in supermarkets! But there is currently no real way of accounting for this in the algorithms underpinning AI.

To me, this feels as though the computer sciences community wrote a giant IOU: ‘insert actual model of human decision making here.’ There is a deep philosophical tension between this outrageous simplification of human values and decision making, and their use in systems that are becoming increasingly powerful and pervasive in our societies.

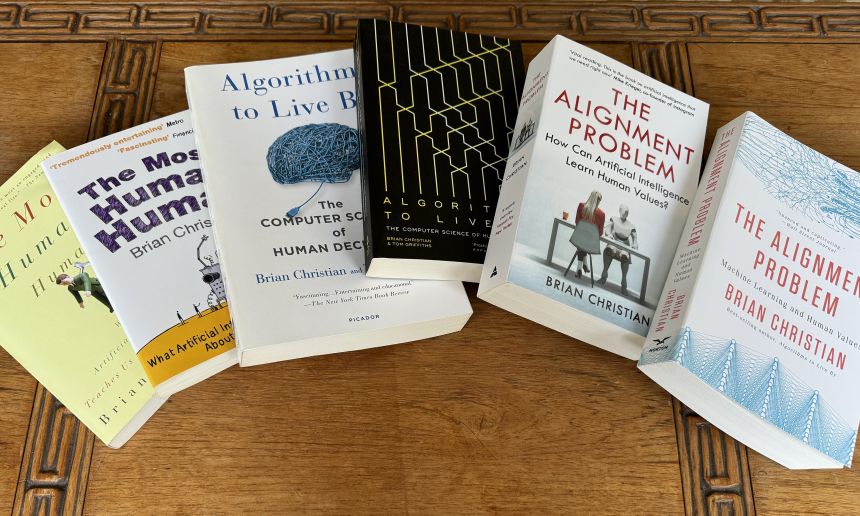

US and UK editions of Brian Christian’s three books on artificial intelligence. Credit: Brian Christian.

US and UK editions of Brian Christian’s three books on artificial intelligence. Credit: Brian Christian.And how will you investigate this?

I am currently developing a roadmap with Chris and my co-supervisor Associate Professor Jakob Foerster (Department of Engineering Science) that will involve both simulations and human studies. One fundamental assumption in the AI literature that we are probing is the concept of “reward.” Standard reinforcement-learning models assume that things in the world simply have reward value, and that humans act in order to obtain those rewards. But we know that the human experience is characterized, at a very fundamental level, by assigning value to things.

There’s a famous fable from Aesop of a fox who, failing to jump high enough to reach some grapes, declares them to have been “sour” anyway. The fox, in other words, has changed their value. This story, which has been passed down through human culture for more than two millennia, speaks to something deeply human, and it offers us a clue that the standard model of reward isn’t correct.

This opens up some intriguing questions. For instance, what is the interaction between our voluntary adoption of a goal, and our involuntary sense of what the reward of achieving that goal will be? How do humans revise the value, not only of their goal itself but of the other alternatives, to facilitate the plan they have decided to pursue? This is one example of using the tools of psychology and computational neuroscience to challenge some of the longstanding mathematical assumptions about human behaviour that exist in the AI literature.

We are moving from traditional software, where behaviour is explicitly specified, to machine learning systems that essentially learn by examples. How can we be sure that they are learning the right things from the right examples, and that they will go on to actually behave in the way that we want?

Does the future of AI frighten you?

Over the years I have been frightened to different extents by different aspects of AI: safety, ethics, economic impact. Part of me is concerned that AI might systematically empower people, but in the wrong way, which can be a form of harm. Even if we make AI more aligned, it may only be aligned asymmetrically, to one part of the self. For instance, American TikTok users alone spend roughly 5 billion minutes on TikTok a day: this is equivalent to almost two hundred waking human lifetimes. A day! We have empowered, at societal scale, the impulsive self to get what it wants – a constant stream of diverting content – but there is more to a life well lived than that.

Do you feel academia has an important role in shaping the future of AI?

Definitely. What is striking to me is how academia kickstarted a lot of the current ideas behind AI safety and AI alignment – these started off on the whiteboards of academic institutions like Oxford, UC Berkeley, and Stanford. Over the last four years, those ideas have been taken up by industry, and AI alignment has gone from being a theoretical to an applied discipline. I think it is very important to have a heterogenous and diverse set of incentives, timescales, and institutional structures to pursue something as big, critical. and multidimensional as AI alignment.

Academia can also have more longevity than industrial research labs, which are typically at the mercy of profit motivations. Academia isn’t so tied to boom and bust cycles of funding. It might not be able to raise billions of dollars overnight, but it isn’t going to go away with the stroke of a pen or a shareholder meeting.

Oxford's unique college system really fosters a sense of community and intellectual exchange that I find incredibly enriching. It is inspiring, it gives you new ideas, and provides a constant reminder of how many open frontiers there are, how many important and urgent open problems.

Why did you choose Oxford for your PhD?

I came to Oxford many times to interview researchers while working on The Alignment Problem. At the time, the fields of AI ethics, AI safety, and AI policy were just being born, with a lot of the key ideas germinating in Oxford. I soon became enamoured of Oxford as a university, a town, and an intellectual community - I felt a sense of belonging and connection. So, Oxford was the obvious choice for where I wanted to do a PhD, and I didn’t actually apply to anywhere else! What sealed it was finding Chris Summerfield. He has a really unique profile as an academic computational neuroscientist who has worked at one of the largest AI research labs, Google DeepMind, and now at the UK’s AI Safety Institute. We met for coffee in 2022 and it all went from there.

What else do you like about being a student again?

Oxford's unique college system really fosters a sense of community and intellectual exchange that I find incredibly enriching. In the US, building a community outside your particular discipline is not really part of the graduate student experience, so I have really savoured this. It is inspiring, it gives you new ideas, and provides a constant reminder of how many open frontiers there are, how many important and urgent open problems. When you work in AI, there can be a tendency sometimes to think that it is the only critical thing to be working on, but this is obviously so far from the truth.

Outside of my work life, I play the drums, and a medium-term project is to find a band to play in. Amongst many other things, Oxford really punches above its weight on the music scene, so I am looking forward to getting more involved in that. Once the weather improves, I also hope to take up one of my favourite pastimes – going on long walks – to explore the wealth of surrounding landscape. As someone who spends a lot of time sitting in front of computers while thinking about computers, it is immensely refreshing to get away from the world of screens and step into nature.

The world’s most powerful computer hasn’t yet been built – but we have the blueprint, says the team behind Oxford spinout Quantum Dynamics.

Meanwhile, Chris Ballance, co-founder of spinout Oxford Ionics, says ‘quantum computing is already solving complex computing test cases in seconds – solutions that would otherwise take thousands of years to find.’

Following decades of pioneering research and development – much of it carried out at the University of Oxford –some of the world’s most innovative companies have integrated their technology into existing systems with excellent results.

Ask a quantum scientist at the University of Oxford for a helpful analogy and they may direct you towards the Bodleian library: a classical computer would look through each book in turn to find the hidden golden ticket, potentially taking thousands of years; an advanced quantum computer could simply open every book at once.

From drug discovery and climate prediction to ultra-powerful AI models and next-generation cryptology and cybersecurity, the potential applications of quantum computing are near-limitless. We’re not there yet, but a host of quantum-based companies with roots in Oxford academia are driving us towards a world of viable, scalable and functional quantum computers – and making sure we’ll be safe when we get there.

With the UK government’s recent announcement to inject £45 million into funding quantum computing research, the future is looking brighter for getting these technologies out into the real world.

Let’s meet some Oxford spinouts leading the charge.

Quantum Motion Technologies

Research suggests that, as with today’s smartphones and computers, silicon is the ideal material from which to make qubits – the basic units of quantum information and the building blocks of quantum computers. Formed in 2017 by Professor Simon Benjamin of Oxford’s Department of Materials and Professor John Morton at UCL, Quantum Motion is developing scalable architecture to take us beyond the current small, error-prone quantum computers.

PQShield

Any news article about the benefits of quantum computing is also likely to highlight a threat: the potential of quantum technology to shatter today’s encryption techniques (imagine a computer able to guess all possible password combinations at once). PQShield, spun out of Oxford’s Mathematical Institute by Dr Ali El Kaafarani, uses sophisticated maths to develop secure, world-leading ‘post-quantum’ cryptosystems. The team has the largest assembly of post-quantum crypto specialists in the world, servicing the whole supply chain.

Orca Computing

Making quantum computing a practical reality is what drives the team at Orca, spun out of research developed at the University of Oxford in 2019. The company is developing scalable quantum architecture using photonics – the manipulation of light – as its basis. In the short-term, that means creating usable technology derived from repurposing telecoms for quantum. This enables the team to build massive-scale information densities without resorting to impossible numbers of components. In the longer-term, Orca’s approach means error-corrected quantum computers with truly transformative potential. Dr Richard Murray, CEO and co-founder, explains: ‘Thanks to our drive towards delivering commercially realistic solutions, we are addressing the consumption of quantum.’

Oxford Ionics

Co-founded in 2019 by Dr Chris Ballance of Oxford’s Department of Physics, Oxford Ionics’ qubits are composed of individual atoms – the universe’s closest approximation to a perfect quantum system. These high-performance qubits have won Oxford Ionics a £6m contract to supply a quantum computer to the UK’s National Quantum Computing Centre in Harwell, Oxfordshire, with the aim of developing new applications.

QuantrolOx

To build practical quantum computers, scientists will need millions of physical qubits working in constant harmony – a big challenge to scaling up. QuantrolOx’s AI software automates the ‘tuning’ process, allowing quicker feedback and better performance. The company, co-founded by Professor Andrew Briggs of Oxford’s Department of Materials, envisions a world where every quantum computer will be fully automated.

Oxford Quantum Circuits

Oxford Quantum Circuits’ quantum computer is the only one of its kind commercially available in the UK. The company, founded by Dr Peter Leek of Oxford’s Department of Physics and today led by founding CEO Ilana Wisby, is driving quantum technology out of the lab and directly to customers’ fingertips, enabling breakthroughs in areas such as predictive medicine, climate change and AI algorithms. Ilana’s vision is for ten machines in ten countries within ten years..

Other innovations in processing power

As quantum computing continues to progress – but with the timeline for adoption unclear – innovators in Oxford are also looking for ways to turbocharge today’s computing technology.

Salience Labs

The speed of AI computation doubles every few months, outpacing standard semiconductor technologies. Salience Labs, a joint spinout of Oxford and Münster universities, is building photon-based – rather than electron-based – solutions to allow us to keep up with exponential AI innovation and the vast amounts of information that require processing in the 21st century.

Lumai

AI’s ability to analyse vast datasets at rapid pace is one of its big selling points. Trained models can produce diagnoses from a patient’s medical images or help insurance companies detect fraud. Oxford spinout Lumai works at the nexus of 3D optics and machine learning to provide an energy-efficient AI processor that delivers computation speeds 1,000 times faster than traditional electronics, enabling AI inference to move to the next level.

Machine Discovery

Harnessing its proprietary neural network technology, Machine Discovery makes complex numerical simulations quicker and cheaper. The Oxford Department of Physics spinout aims to provide its customers with all the benefits of machine learning – without the years of AI research. Its ‘Discovery Platform’ technology allows users to describe their problem and let the software find the solution.

Kelsey Doerksen is a DPhil student in Autonomous Intelligent Machines and Systems at the Department of Computer Science, and the President of the Oxford Womxn in Computer Science Society. She is also a Giga Data Science Fellow at UNICEF and a Visiting Researcher at European Space Agency.

There is enormous potential for artificial intelligence (AI) tools to benefit society; from early detection of diseases, to natural disaster response, to helping us write succinct emails. But these technologies need to be viewed under a critical lens to ensure that we are building tools to help, and not harm society.

When we are thinking about reducing bias in AI models, we need to start with the datasets we are using to teach them. AI models are being trained on datasets which we know have systematically left minorities out of the picture; resulting in data that lacks diverse representation of gender identities, sexual orientations, and race, among others. AI can be a powerful tool to mitigate human-induced bias because it is a data-driven approach to decision making, but if the data it is using has biases, this becomes an issue. For example, we have seen generative AI adopting stereotypes and biases when generating images of certain professions that we typically associated with men or women in the past.

In addition to bias mitigation from a data perspective, it is critical that the diversity of users of an AI product are represented at the development stage. Improving gender representation in AI and Computer Science (CS) is something I am very passionate about, and being a part of the Oxford Womxn in Computer Science Society (OxWoCS) for the past three years has been transformative to my experience as a woman in the field.

The success of the society speaks for itself, we have grown to 250+ members with over 750 people on our mailing list, providing academic, career and social opportunities to the CS community at Oxford University across all levels of study and research. My experience leading OxWoCS as the 2023-24 President has been one of the highlights of my DPhil. It has been incredibly rewarding to connect with so many women in the field who are equally as passionate about their research as they are about building a welcoming and safe community for gender minorities in the space.

My hopes for the future of women in the fields of AI and CS is that we continue to champion and advocate for one another to build stronger communities that celebrate the diversity of experiences that we bring to the table.

* 'Artificial intelligence and gender equality: how can we make AI a force for inclusion?' was the topic of a panel discussion co-hosted by the Vice-Chancellor Professor Irene Tracey CBE, FRS, FMedSci and Professor Tim Soutphommasane, Chief Diversity Officer on 6 March 2024 ahead of International Women's Day.

- ‹ previous

- 7 of 253

- next ›

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools