Features

As England's footballers struggle to deal with the effects of altitude on their bodies ahead of their first World Cup match in South Africa, they may wonder how people living day in day out at even higher levels get by at all.

A new study published this week in PNAS reveals that natural selection has enabled humans to better cope with living in Shangri La.

Shangri La here is not the mythical Eastern earthly paradise, but the very real province high up in the Tibetan plateau where the indigenous population lives at altitudes of 3,200m to above 4,000m – much greater than the 1500m Gerrard, Lampard and the rest will be playing at on Saturday.

The international team of researchers from the UK, Ireland, China and the US searched for evidence of selection at the genetic level among people living at these high altitudes where there is so little oxygen.

The study’s corresponding author, Professor Peter Robbins of Oxford’s Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, confirms that ‘Tibetans are better equipped for life at high altitude.’

People who move to live at high altitudes tend to be at risk of a chronic mountain sickness. The body makes too many red blood cells, giving excessive levels of haemoglobin, in an attempt to capture the little oxygen there is in the air. But native Tibetans manage to remain unaffected.

So the scientists compared the genetic profiles of groups of Tibetans living at these high altitudes with nearby populations in lowland China, and they found changes in a single gene were present at high frequency among the Tibetans.

The researchers showed that having a different version of the EPAS1 gene gives Tibetan populations an advantage: it keeps levels of haemoglobin low and so protects them against developing chronic mountain sickness. ‘This is where individuals make too many red cells and the blood becomes very sticky,’ says Peter Robbins. ‘[Having the EPAS1 variant] may also help with reproductive fitness at high altitude, but that is more speculative.’

This is good evidence that the lack of oxygen at these altitudes has exerted an evolutionary selection pressure over the 10,000 years or more people have been living in these areas.

‘There are probably not more than a handful of definitive examples of human evolution to their environment at the genetic level that have so far been described,’ says Peter Robbins. ‘There are genes for variation in skin colour, certain genes that confer protection against malaria (for malaria infested environments) and possibly one or two dietary adaptations (but these are a bit more speculative).’

There may also be some pay off from this work for future English footballers (or, depending on the result, fewer excuses):

EPAS1 – also known as HIF2a (hypoxia-inducible factor 2) – is a major gene involved in keeping oxygen levels stable, explains Peter Robbins. ‘As oxygen transport is the principal limiting factor to much endurance exercise, everything we can understand in relation to human variation here will probably help us to understand better the constraints on athletic performance.’

‘In addition, as low oxygen (hypoxia) is a feature of so much disease (eg lung disease, heart disease, vascular disease, cancer), understanding human variation in the response to low oxygen may help us to understand why some people seem so much better at surviving conditions of low oxygen than others.’

Great news: our post about Oxford & the Royal Society's origins has been nominated for the 3quarksdaily science blogging awards.

These annual awards celebrate the very best in blogging and this is the second year that 3quarksdaily have given a prize for science posts. We're in excellent company with posts from such great blogs as The Loom, Bad Astronomy, and Not Exactly Rocket Science.

Our post delved into the fertile chaos of 1650s Oxford and how an eclectic mix of figures from the University would go on to play a key role in the founding of the Royal Society (which celebrates its 350th birthday this year) and set Britain on the path to becoming a scientific superpower.

But of course, to stand any chance of winning, we need your votes! So if you'd like us to win go to the 3quarksdaily voting page, look for 'University of Oxford Science Blog', and vote for us!

UPDATE: 8 June: Thanks to everyone who voted for us! Our post came 7th in the public vote and made the semi-final.

UPDATE: 11 June: A nice surprise, our post has made the final.

Nanocapsules

Nanocapsules

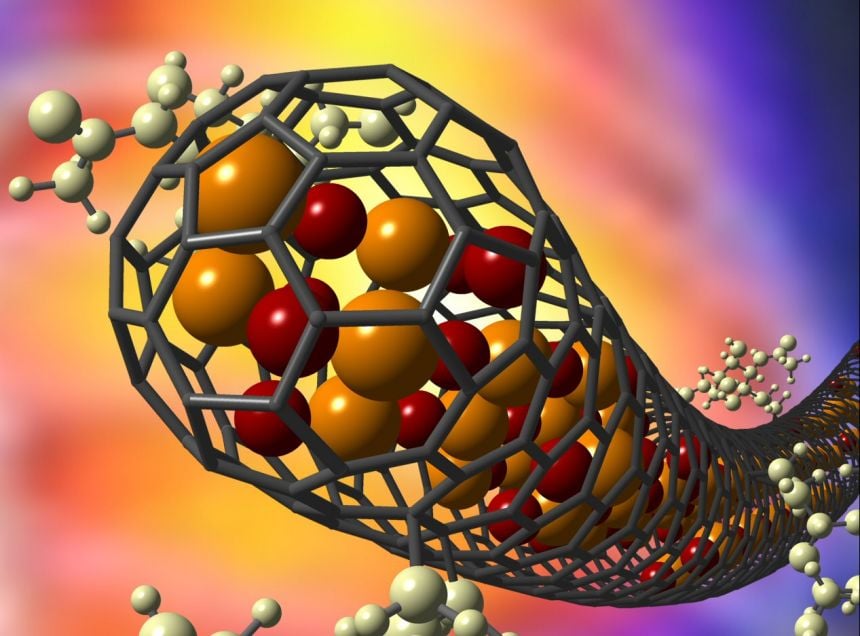

‘Hot’ nanocapsules can deliver targeted radiotherapy to individual organs, new research has shown.

A team, including Ben Davis and Malcolm Green of Oxford University’s Department of Chemistry, report in Nature Materials how they created a ‘cage’ out of a single-walled carbon nanotube and then filled this tube with molten radioactive metal halide salts.

Once the cage, and its cargo of salts, cooled the ends of the tube sealed to create a tiny radioactive nanocapsule with a ‘sugary’ outer surface that helps to improve its compatibility inside the body.

Using this method the team were able to create nanocapsules that could deliver a highly concentrated dose of radiation (800% ionizing dose per gram) of the kind needed for radiotherapy. They then used mice to test how these radioactive nanocapsules would be taken up by the body.

They found that the nanocapsules accumulated in the lung tissue but not in the thyroid, stomach, or bladder as occurred with ‘free’ doses of radioactive salts introduced without first being encapsulated. Even after a week in the body the nanocapsules remained stable without any significant leaking of radiation beyond the lung.

Whilst a lot of further work would be needed to create a treatment for humans, it’s the first time that researchers have shown how such a nanocapsule system for targeted radiotherapy might be made to work inside the body.

As the accompanying News & Views article notes this demonstration shows that: ‘radiosurgery at the nanoscale, from within the human body may have moved a step closer from science fiction to clinical practice.’

If you’re anything like us, you’ve been enjoying the BBC’s The Story of Scienceseries with Michael Mosley, which charts the progress of science through the centuries.

Professor Pietro Corsi of Oxford University's Faculty of History was one of three leading historians of science that acted as consultants to the series. So what’s been his view of the final result?

‘I think it’s been a success. As a viewer I enjoyed it enormously, though as a historian I sometimes wished we’d been able to say more!’ says Pietro. It’s clear from the way he talks that he very much enjoyed the process of working with the TV producers and is proud of the outcome.

Covering the whole history of science in a six-part series is of course a dauntingly impossible task.

‘The difficulty was that we had this immense domain and we had to make choices about what to cover. The outcome represents a gallant, honest effort to do that while going beyond the usual stories of scientific advances and individual geniuses: apples falling in Newton’s lap and Darwin’s trip to the Galapagos,’ says Pietro.

He is clear: ‘These stories become myths. They take science away from reality.’

For Pietro, science is a more socio-political affair that can’t be divorced from the complexities of real life. Scientists are not independent from their social, political, religious and cultural surroundings. They are real personalities whose work happens alongside the plots, dynastic powers and troubled waters of the time.

‘The message of the series is that history makes science,’ Pietro states. He illustrates this with one of the stories from the first episode of The Story of Science.

Galileo was in Venice when he heard that a French traveller was on his way to showcase a new Dutch discovery – the telescope – in the city. Since Venice had its renowned glass making industries to hand, Galileo was able to manufacture excellent glass lenses and construct his own telescope. This he successfully offered to the Venetian Republic to aid its military defences, and the Republic granted him a substantial reward. Galileo immediately started to use the telescope for his astronomical work. In March 1610 he announced the momentous discovery of Jupiter’s satellites, of the phases of Venus, and later on of the existence of mountains on the Moon.

‘Galileo immediately exploited the potential of the telescope for commercial benefit,’ explains Pietro. ‘He negotiated through his discovery an important job in Florence. Here he went on to do the work that made him a hero of astronomy, but he had got there by looking after his own career first.’

Pietro feels that it is important for modern scientists to realise that science isn’t independent from the society in which it is conducted: ‘In many areas, it is important to understand how the power of science has been acquired and how it can be lost. People assume science will continue forever. History tells us that science empires have risen and fallen as fast as political emperors, and science’s standing should not be taken for granted.’

He points out that 1500 years ago, Kabul in Afghanistan was one of the major astronomical centres of the Muslim world. Scientific golden ages have also risen and fallen in India and China (and of course are now on the rise again).

‘In contemporary society, science is often seen as independent from the society in which it operates. But science has always needed patrons, even if today those patrons are the state, a company or the military. Society might have a wish to decide more and more about which subjects shall receive that patronage or funding.’

Pietro thinks it is extraordinary that in science – such a major enterprise in today’s world – knowing the history of a field’s development is considered not necessary or is not understood by most. In other words, that in spite of the key role science plays in our individual and collective life, so little attention is paid to acquiring a better understanding of its historical and recent development.

I get the feeling that Pietro thinks that appreciating this extra aspect of how science develops is empowering. He points out that the number of people doing science today would have been unthinkable in the past. The contemporary scale of science has never been seen before.

‘The reality of mass science today is that people can end up being more like technicians,’ he says. If we are to get more people taking up scientific careers, a sense of the history of the subject can give a sense of purpose. ‘That way it’s not reduced to solving small problems here and there,’ Pietro concludes.

Food for thought as we wait for the next instalment of The Story of Science at 9pm tonight.

They float like tiny jewels encased in stone: most are only a few millimetres or centimetres long but full of incredible detail – boasting tiny tentacles, eyes, legs, and forceps-like pincers.

‘Many of them are entirely soft-bodied, they have no right to be preserved over 525 million years. They should really have quickly decomposed on the sea bottom, or have been eaten, or destroyed over millions years of earth history’ explains Derek Siveter of Oxford University’s Museum of Natural History and the Department of Earth Sciences.

These are the Chengjiang fossils from Yunnan, China, on display at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, in the first major exhibition of these fossils outside China.

The Chengjiang fossils, first unearthed in 1984, are particularly important because they open up a window onto one of the most important events in the history of life: the so-called Cambrian 'explosion' when most of the major animal groups we know today first appeared in the fossil record.

The big question has always been: where did this dazzling variety of animals come from? Did they suddenly develop or were earlier examples of complex animals simply never preserved?

These particular fossils have survived because of an amazing stroke of luck: ‘The preservation of all the soft tissues is a result of the organic materials of these animal bodies being replaced by ‘fool’s gold’ – iron pyrites. It means their forms have been captured for posterity,’ Derek tells me.

At first glance they may not be as impressive as the Museum’s dinosaur skeletons or stuffed dodos but, get your nose close enough to the glass cases, and you’ll enter a different world.

More than 100 species have been recognised from these golden-coloured fossils:

There are examples of groups that include velvet worms (lobopodians) that Derek describes as ‘worms with legs’, 'lamp-shells' (brachiopods) looking like balloons (the body) on the end of a piece of string (the soft, fleshy, tethering stalk), and ancient arthropods, some of them the ancestors of modern horseshoe crabs with armoured bodies and forceps-like appendages – probably for grabbing on to prey – and others probably representing forms that we would identify as crustaceans (this group today includes crabs, lobsters and shrimps).

‘The collection, significantly, also includes the earliest example from the fossil record of what is generally agreed to be a vertebrate,’ Derek reveals.

But as well as these familiar-looking creatures are others that might go unnoticed but are nevertheless vital scientific finds. One example is the sea gooseberry (ctenophore), which looks like a cross between a soft fruit and a diving bell.

There are some 100 species of sea gooseberry floating in today’s oceans and the Chengjiang fossils show examples of these creatures, some with branched tentacles, which like their modern cousins probably captured their dinner by engulfing it.

Derek comments: ‘Here we have examples of the sea gooseberry. They are exceptionally rare as fossils, numbering just a handful of specimens from just a very few localities anywhere on Earth, and the Chengjiang examples are the oldest.’

‘These miraculously-preserved examples give us rare insights into the very early nature of the sea gooseberry and help determine the timing of the origin of this animal group and its place within the tree of life.’

The exceptional preservation of these fossils (in what researchers call a lagerstatte) makes it possible to examine the remains of soft-bodied animals in intricate detail, and such preservation can often give us a much better idea of how they might have behaved:

The wonderful ‘daisy chain’ fossil creatures, that we reported on back in 2008, are one example of this: shrimp-like animals that have congregated together perhaps for reproduction, or more likely as part of some Cambrian migration through the ancient seas.

If you expect life from 525m years ago to look rather primitive then you’re in for a surprise: these fossils reveal fully-formed, finely-adapted animals that seem as sophisticated as many of their relatives we know today – something we wouldn’t be able to say but for their extraordinary preservation.

‘It’s an amazing treasure, it's the Chinese equivalent of the famous Burgess Shale fossils from North America or, put another way, the material is every bit as wondrous palaeontologically as the Terracotta Warriors are archaeologically,’ adds Derek.

The exhibition, ‘Exceptional Fossils from Chengjiang, China:

Early Animal Life’, is on display at the OU Museum of

Natural History 18 May-14 November 2010.

The specimens displayed

are from the Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology, Yunnan University.

- ‹ previous

- 214 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria