Features

Zombies reportedly want to eat our brains ("BRAIIINS!") but what if we could use our grey matter to survive a zombie apocalypse?

Thomas Woolley from Oxford University's Mathematical Institute has been figuring out how maths could help us when an epidemic of the undead is unleashed – and in a fun way explore some of the maths behind the study of real life human diseases.

In a chapter in a new book, Mathematical Modelling of Zombies, Thomas and his co-authors report how their models suggest three top tips for avoiding becoming zombie chow:

1. Run! Your first instinct should always to be put as much distance between you and the zombies as possible.

2. Only fight from a position of power. The simulations clearly show that humans can only survive if humans are more deadly that the zombies.

3. Be wary of your fellow humans.

But assuming the shuffling hordes aren't already battering down your front door, I thought I’d take time out from stockpiling cricket bats, shotgun cartridges, and tinned food to quiz Thomas about maths, zombification, and watching your back…

OxSciBlog: How does zombie modelling relate to modelling real diseases?

Thomas Woolley: Mathematics can model the spread of any disease. The critical task in constructing a specific disease model lies in understanding the mechanisms by which the disease is able to spread. Canonically, zombies transmit their disease through biting a victim. Thus, like many real diseases, such as AIDS and Ebola, transmission occurs through contact with infected body fluids. As such, we model a zombie infection using the same techniques and equations that are used to model the aforementioned real diseases.

One of the main differences between zombiism and a real disease is that with a real disease there is usually some hope of a cure, treatment, or recovery. Unfortunately, this does not appear to be the case for zombification. This lack of recovery is one of the primary reasons why it is so hard to stop the apocalypse scenario that appears in numerous zombie films.

OSB: Why, mathematically, is running away from zombies a good strategy?

TW: Our model is based on the idea that zombies move around using a random walk. Explicitly, they are mindless animals that simply lurch from position to the next with no purpose or direction (we apologise for hurting the feelings of any intelligent zombies who are currently reading this). Through this assumption we find that the zombie's motion is described by the diffusion equation.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the diffusion equation. Whenever movement can be considered random and directionless, the diffusion equation will be found. This means that, by understanding the diffusion equation, we are able to describe a host of different systems such as heat conduction through solids, gases (eg smells) spreading out through a room, proteins moving around the body and molecule transportation in chemical reactions, to name but a few of the great numbers of applications.

Through the use of the diffusion equation we find that the time for a human-zombie interaction is quadratically proportional to the distance separating the humans and zombies, whilst linearly proportional to the zombie diffusion constant, which measures the rate at which the zombies move. Explicitly, this means that if you double the distance between you and a zombie, then the time before your interaction quadruples. However, if you slow the zombies down by a half then the interaction time only doubles. Hence, we see that running away, rather than slowing the zombies down, is the better way of rapidly increasing the time before an interaction.

OSB: What difference does how deadly humans are compared to zombies make?

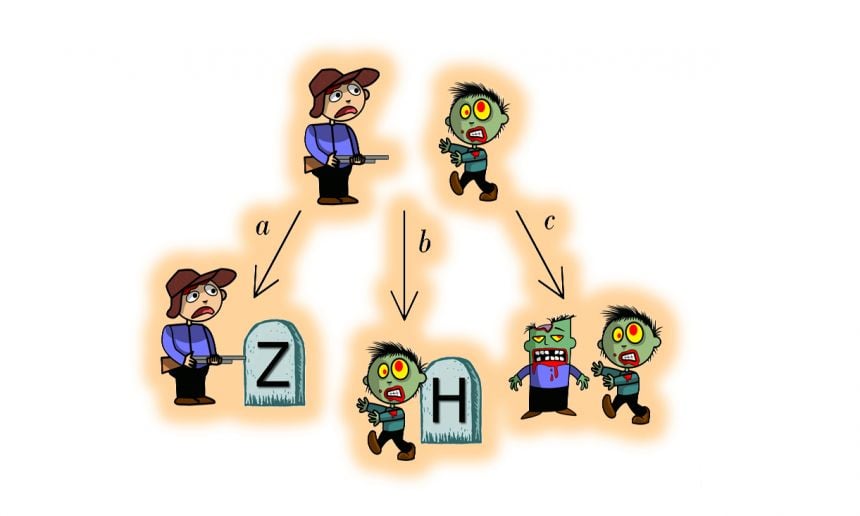

TW: In our model we suppose that there are three different interactions that can occur:

humans kill zombies at a rate a;

zombies kill humans at a rate b;

humans become zombified at a rate c.

These interactions are illustrated in the figure below. The only way that humans can survive is if we can wipe out the zombie menace. If any remain then they will always represent a potential threat. This means that humans have to kill the zombies at a rate faster than they are created, explicitly we need the rate a to be great than the rate c. Unfortunately, if the zombies are very infectious and very resilient to our attacks then c will be greater than a and we find that an infection wave can take hold in the susceptible population. This results in a scenario where everyone is eventually wiped out.

Illustration of three possible zombie interactions considered in the model

Illustration of three possible zombie interactions considered in the modelPhoto: Thomas E Woolley, with thanks to Martin Berube who provided the zombie figures.

OSB: Why might maths suggest that you turn on your fellow humans?

TW: An infection wave can only happen if there are susceptible people to be infected. Critically, the speed of the infection wave depends explicitly on the initial number of susceptible people. If you are able to isolate yourself geographically on an island then you should be completely safe (excluding such cases that occur in the film Land of the Dead).

However, suppose you are not lucky enough to live on an island and, instead, you in an office block when the dead begin to rise. Everyone around you is a potential zombie. Thus, be careful to pick your colleagues carefully. If they are all weak then you might want to think about dispatching them.

Alternatively, if you are the weak connection, make sure that someone is not trying to get rid of you. Of course I and the other authors would not recommend such unethical behaviour. The population will have enough trouble trying to survive the hordes of undead, without worrying about an attack from their own kind!

People involved in arts and sciences around Oxford are joining forces to hold a festival on the theme of breath and breathing next Saturday (1 November). The one-day Breath Festival comprises events, talks, performances and exhibitions in venues across Oxford.

Oxford University will curate a series of free 'Breath Talks', a series of TED-style short presentations by academics and artists on all the ways in which breath speaks to us. Dr Emma Smith, a Shakespeare expert at the University, will talk about King Lear and the relationship between language, performance and breath. Dr Kevin Hilliard of the Modern Languages Faculty will talk about the ways in which 18th Century German poems enact heavenly breathing patterns in their verse.

During the day Oxford University's museums will put on special displays, performances, tours, talks and children's activities concerned with breath. Visitors can also take 'Breath Tours' of the Museum of Natural History and Pitt Rivers throughout the day. The Museum of Natural History will host a session of singing activities led by Singing for Better Breathing, a local Sound Resource project encouraging people with respiratory problems to sing.

In the evening two performances of a new composition, Breathe, will take place at the North Wall Arts Centre. Breathe was composed by Orlando Gough, having been developed through research with John Stradling, Emeritus Professor of Respiratory Medicine at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust. The composition marks the tercentenary of the death of Dr John Radcliffe, who generously donated the funds to enable the building of the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford’s first hospital.

Professor Abigail Williams, an English academic at Oxford University, said: 'The Breath Talks are an eclectic and inspiring collection of talks from experts in many different disciplines. From King Lear to wind turbulence, devotional verse to Inuit breath music, they will explore how breath has been thought about, illustrated and performed throughout history.'

Lucy Shaw, Manager of Oxford University Museums partnership, said: 'Oxford University Museums are really delighted to be part of the Breath Festival. The activities, performances and displays, which make up the festival, bring together original work and thinking of artists, scientists, academics and curators in order to inspire, excite and inform our audiences.'

The Breath Project has been developed by artlink, the arts programme for Oxford University Hospitals Trust, in conjunction with Oxford University’s Humanities Division, Oxford University Museums, Oxford Contemporary Music and Singing for Better Breathing. It is supported by ORH Charitable Funds, The Radcliffe Trust, a Wellcome Trust Arts Award and Arts Council England.

Stammering is a common condition in children that may last into adulthood and can affect people's self-esteem, education and employment prospects.

22 October is International Stammering Awareness Day and sees the launch of a new Oxford University trial investigating whether a form of non-invasive brain stimulation could help people who stammer achieve fluent speech more easily and make this fluency last longer.

I asked Kate Watkins and Jen Chesters of Oxford University's Department of Experimental Psychology, who are leading the new trial, about the science of stammering, what the trial will involve, and how brain stimulation could improve current therapies…

OxSciBlog: What is stuttering/stammering? How many people have a stammer?

Kate Watkins: Stammering (also known as stuttering) affects one in twenty children and one in a hundred adults. About four or five times more men than women are affected.

The normal flow of speech is disrupted when people stammer. The speaker knows what he or she wants to say but has problems saying it. The characteristics of stammering include production of frequent repetitions of speech sounds, and frequent hesitations when speech appears blocked. Children and adults who stammer can sometimes experience restrictions in their academic and career choices. Some people some suffer anxiety as a result of their speech difficulties.

OSB: What do we think causes people to stammer?

KW: The cause of stammering is unknown. Using MRI scans we have noticed small differences in the brains of people who stammer when compared with those of people who speak fluently. For example, we found differences in the amount of brain activity that occurs during speech production in people who stammer even when they are speaking fluently.

These brain imaging studies indicate abnormal function of brain areas involved in planning and producing speech, and in monitoring speech production. We have also used MRI scans to look at how these brain areas are connected and found that the white matter connections between these regions are disrupted in people who stammer.

A striking feature of stammering is that complete fluency can be achieved by changing the way a person perceives his or her own speech (so by altering the way the speaker hears his or her own voice). For example, masking speech production with noise (or loud music as demonstrated in the film The King's Speech or by Musharraf on Educating Yorkshire) can temporarily eliminate stuttering. Delaying auditory feedback of speech, altering its pitch, singing, speaking in unison with another speaker, or speaking in time with a metronome are all ways of temporarily enhancing fluency in people who stammer. These observations tell us that the cause of stammering may be due to a problem in combining motor and auditory information.

OSB: What treatments/therapies can people currently get for stammering?

Jen Chesters: Speech and Language Therapy for people who stammer may involve learning to reduce moments of stammering, or decrease the amount of tension when stammering. Techniques such as speaking in time with a metronome beat, or lengthening each speech sound can immediately increase fluency.

However, these approaches make speech sound unnatural, so moving towards fluent yet natural-sounding speech is the main challenge during therapy. Even when these methods are mastered within the speech therapy clinic, continual ongoing practice is needed for fluency to be maintained in everyday life. The fluency-enhancing effects can also just 'wear off' over time, even when these techniques are practised regularly. For all these reasons, therapy for adults who stammer often focuses instead on learning to live with the disorder.

OSB: How might brain stimulation improve on these?

JC: Non-invasive brain stimulation is a promising new method for treating disorders that affect the brain's function. The method we use is called transcranial direct current stimulation (or TDCS for short). TDCS involves passing a very weak electrical current across surface electrodes placed on the scalp, and through the underlying brain tissue (it doesn't hurt!). This stimulation changes the excitability of the targeted brain area. TDCS applied during a task that engages the stimulated brain region, can increase and prolong task performance or learning.

TDCS has been used in rehabilitation studies, for example it has been applied to brain regions involved in speech and language to increase these functions in patients who have problems with speech (aphasia) following a stroke. We are interested in how TDCS could help people who stammer to achieve fluent speech more easily, and maintain their fluency for longer. TDCS may have the potential to increase speech therapy outcomes, or to reduce the high levels of effort and practice that are needed in traditional speech therapy for stammering. Our research aims to explore this potential.

OSB: What is the aim of your new trial?

JC: In this study, we want to see how the effects of a brief course of fluency therapy might be increased or prolonged by using TDCS. We will use some techniques that we know will immediately increase fluency in most people who stammer, such as speaking in unison with another person or in time with a metronome. However, these techniques would normally need to be combined with other methods to help transfer this fluency into everyday speech. We will investigate how TDCS might help maintain the fluent speech that is produced using these methods.

OSB: What will volunteers be asked to do?

JC: Volunteers will be invited to have fluency therapy over five consecutive days, whilst receiving TDCS. In order to measure the effects of this intervention, they will also be asked to do some speech tasks before the fluency therapy, one week after the fluency therapy, and again six weeks later. We are also interested in how this combination of therapy and TDCS may change brain function and structure. So, volunteers will also be invited for MRI scans before and after the therapy.

OSB: How do you hope the trial results will benefit patients/your research?

JC: The results of the trial will give us a first indication about whether TDCS might be a useful method to develop for stammering therapy. The research is in its early stages, so the results of this study will not cross over into the speech therapy clinic just yet. However, we are hoping to see whether TDCS shows promise for improving speech therapy outcomes. If it does, further research would be needed to explore how TDCS can be combined with speech therapy to achieve the greatest improvements for people who stammer.

We all know that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are a problem – maybe even 'as big a risk as terrorism'* – but how is this resistance passed on from one bug to another?

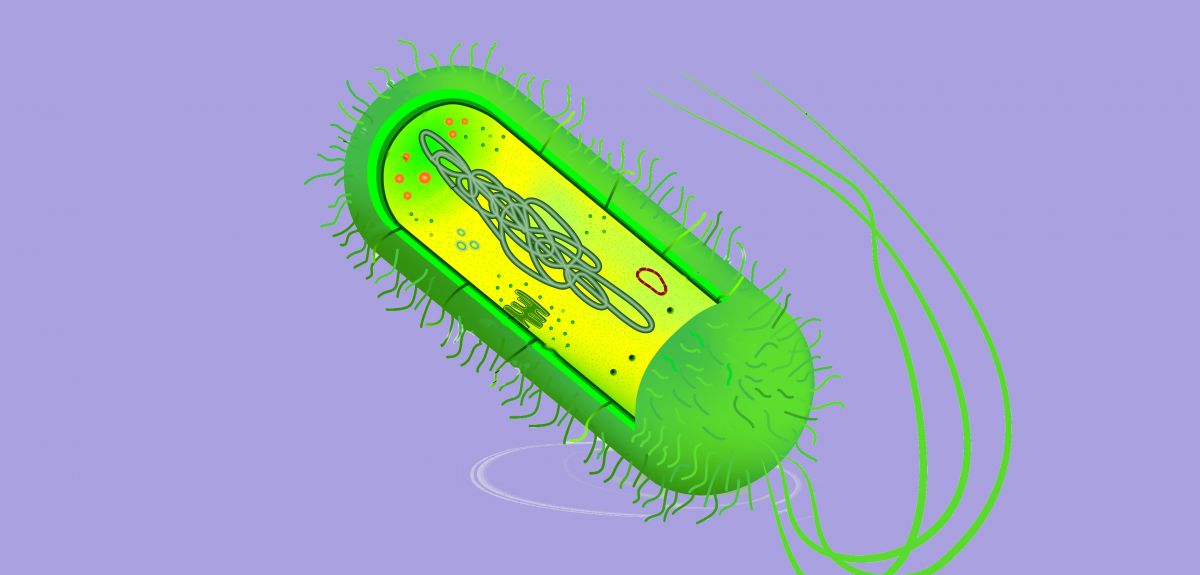

One key culprit is plasmids: these are small 'hula hoops' of DNA that occur naturally within the cells of bacteria (and some eukaryotes) and are completely independent of the main bacterial genome.

'Plasmids carry genes that help bacteria to adapt to new niches and stresses, playing a key role in bacterial evolution,' said Alvaro San Millan of Oxford University's Department of Zoology. 'In the last decades they have become especially relevant as vehicles for the spread of antibiotic resistance. Understanding the biology and evolution of plasmids is key to controlling the global threat posed to human health by antibiotic resistance.'

Not only do plasmids replicate, copying across to a daughter cell when a bacterium divides, but they can also pass between unrelated bacteria through mechanisms such as cell-to-cell contact or a 'bridging connection' in a process called 'conjugation' – which has been described as the bacterial equivalent of sex.

Alvaro explains that plasmids usually transfer not just one but a number of ways to fight off antibiotics: 'they confer multi-resistance en bloc, in only one step, jeopardising the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy.'

But there are a couple of reasons why plasmids shouldn't be such a problem:

For a bacterium, carrying a plasmid around is a bit like having a free-loading lodger. In situations where the lodger is providing a useful service, such as protecting you from antibiotics when antibiotics are killing off your rivals, then it can give you an advantage. Take those antibiotics away, however, and the evolutionary costs begin to mount so that a plasmid-free bacterium should fare better.

And then there's conjugation: a recent analysis has shown that almost half of the plasmids in nature lack the genetic tools required for conjugation. So how do non-conjugative plasmids survive?

Alvaro and colleagues set out to investigate this plasmid puzzle using a combination of mathematical modelling and experimental evolution and report their findings in a recent article in Nature Communications.

What they found is that, after exposure to antibiotics, bacteria evolve compensatory adaptions to mitigate some of the cost of carrying a plasmid. The adapted plasmid-carriers are selected in the next exposure to antibiotics and when the antibiotic is removed, plasmids are eliminated much more slowly from the population because they no longer come with a cost. Any subsequent exposure to antibiotics will cause the population of plasmid-carriers to bounce back as their resistance once again becomes an advantage, increasing their chances for further adaptations.

'It appears that adaptation between plasmid and bacteria coupled with rare events of antibiotic treatment are enough to stabilise a non-conjugative plasmid in a bacterial population,' Alvaro tells me. 'Our results provide a new understanding of how plasmids can persist in bacterial populations and help to explain why plasmid-mediated resistance can be maintained after antibiotic use is stopped.'

He adds: 'Our paper shows how antibiotic use plays a key role in stabilising resistance genes in pathogen populations, highlighting the importance of minimising antibiotic use for controlling resistance.'

The researchers say that more studies are needed into how plasmids evolve and survive in bacterial populations so that we can design intervention strategies aimed at reducing the spread of antibiotic resistance.

This year's Man Booker Prize has been awarded to Australian novelist Richard Flanagan, a former history undergraduate at Oxford.

But as far as one of his near-contemporaries at Oxford recalls, Mr Flanagan was not writing a novel while he studied here.

'I actually lived across the road from Richard while we were Rhodes Scholars at Oxford but it was only later when we both started to publish novels that we realised we had this mutual interest,' says Professor Elleke Boehmer, novelist and Professor of World Literature in English at Oxford University.

'I always knew Richard as a very serious and committed environmental campaigner who loved his homeland of Tasmania and the deep south of Australia, and this was very clear in his acceptance speech. I remember him campaigning against the building of a dam in his native Tasmania and the various forestry projects on the island.'

Mr Flanagan's book, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, is set during the construction of the Thailand-Burma Death Railway in World War Two. Professor Boehmer believes the novel is a fitting winner of the Man Booker Prize at a time when we are commemorating World War One.

'Richard’s book explores the question of how we remember war and other situations of conflict, and how we get over (or not) the trauma caused by those events,' she says. ‘It is a brilliant book and deserves to win in what I understand was a close run contest.'

Professor Boehmer attended the ceremony at the Guildhall on Tuesday evening, and will herself be a judge on the panel of next year's International Man Booker prize, which looks at literature written in English and other languages.

Professor Boehmer says that the main challenge of judging the award is the amount of reading required. 'Last night's committee would have had to read 150 novels and we’re probably having to read as much or perhaps even more than that,' she said.

'It is also difficult to make judgements between books that are really fantastic. Often it can help if the topic of a book relates to one that is the focus of public attention in a particular year.'

Despite these challenges, Professor Boehmer says that judging a book prize can also help you as a writer. She said: 'It takes you to a far broader terrain than you might normally read in because you are reading other literary traditions.

'This can help you work your way towards a solution to a common structural problem by seeing how other writers have dealt with that in their own tradition. For example, you can see how others manage multi-voice narratives, or the narrative of a single individual who may be out of touch with their own community—which is quite a common theme.'

A lot of attention focused on this year as the first in which all novels written in English were eligible for the Man Booker Prize, and two American authors were on the shortlist. 'It is interesting that in the first year Americans could be nominated the only Commonwealth writer on the longlist won,' says Professor Boehmer.

'I think it is right any novel in the English language can now be considered, and this year’s award demonstrates that the prize is not necessarily going to be dominated by big American realist novels.'

'It's also a great thing for Australian literature and I hope it will add to the momentum for the Commonwealth Fiction Prize to be revived. It was stopped a few years ago, having been won by Richard in the past, and I’d love to see it restarted.'

Professor Boehmer has two books coming out next year – a novel about the emotional legacy of the Second World War, and a book with Oxford University Press whose working title is ‘Networks of Empire’.

- ‹ previous

- 160 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?