Features

Sexual reproduction produces new combinations of genes, a process that is thought to prevent the accumulation of harmful mutations. A study in Nature Genetics now provides the first experimental evidence that recombining genes stops harmful mutations from piling up in humans.

I talked to the lead researcher, Dr Julie Hussin at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, about the evolutionary biology of sex.

OxSciBlog: Why is the evolution of sexual reproduction still a bit of a puzzle for researchers?

Julie Hussin: Well, because asexual reproduction just makes more sense!

If an organism has got to the stage where it can reproduce, its genes are clearly sufficiently adapted to the environment that it can survive.

From this point of view, it doesn't make sense why you'd risk mixing your genes to make a new, unproven genome, when the genome you already have has been proven to be good enough to survive.

OSB: So what advantage might sexual reproduction offer to a biological organism?

JH: Many decades of theoretical work show that when genes are not mixed together to make new combinations, over many rounds of reproduction mutations which are only slightly harmful slowly begin to accumulate in the organism's genome.

Over time, this can potentially drive the species to extinction.

Sexual reproduction is one way of ensuring that recombination happens each time the organism reproduces, preventing the accumulation of genetic defects.

OSB: You've mentioned that this rationale for sexual reproduction is supported by theoretical work: is there previous experimental evidence supporting it?

JH: Experimental evidence is much thinner, and there has been none in humans.

The problem with demonstrating that human recombinations have an effect on genetic mutations is that they affect mutations that are very rare in the population. The impact of recombination on the accumulation of these mutations is thus detectable within whole populations, rather than in single individuals.

So to find them, we not only needed very large sample sizes, but also data across the whole genome.

It is only recently that we have had the technology to get large-scale genomic data from many, many people: we used high-coverage gene sequencing data from over 1,400 people, collected by the 1000 Genomes and the CARTaGENE projects.

Using this data, we have shown for the first time that recombination rates have an effect on the accumulation of harmful mutations in humans.

OSB: How did you use this data?

JH: The rate of recombination is actually not uniform across the human genome, and rates vary quite dramatically across genomic regions.

So we compared how many mutations had accumulated in regions of the genome where there is a lot of recombination ('hotspots'), versus regions where the recombination rates are low ('coldspots').

Our thinking was that if recombination discourages the accumulation of harmful genetic mutations, then there will be a difference in the proportion of harmful mutations there are in the 'hotspots' versus the 'coldspots'.

OSB: What did you find?

JH: Exactly that: genome regions where the recombination rates are low had many more harmful and disease-associated mutations, compared to genomic regions with high rates of recombination.

What was a surprise was that the genes in the coldspot regions were more likely to be involved in really essential processes, such as DNA repair and cell maintenance. Mutations here were particularly likely to affect the health of people carrying the mutation.

OSB: Why are genes for essential functions located in regions where it turns out that there is greater chance of a harmful genetic mutation?

JH: We don't know.

But it is possible that there is a greater cost for a 'bad recombination event for these genes.

Very occasionally, recombining genes can result in a deleterious variation. When this happens for a very essential gene, the cell simply dies.

From an evolutionarily perspective, genes for essential cellular functions are very old: they evolved millions of years ago, and they've been handed down to many organisms because they clearly work.

So it makes sense not to 'mess' too much with them, and this could be why they're in coldspot genome region.

In contrast, genes in charge of the immune system and immune responses are mainly found in hotspots.

These are relatively new functions: perhaps the new variants that gene recombinations yield are still required here, to better adapt to the environment.

OSB: Did you also find genetic differences between the different human populations you looked at?

JH: Yes!

In older, larger populations, we found a much smaller difference in harmful mutation accumulation in the coldspots versus the hotspots.

For example, we had data from the French-Canadian population, which was established only 400 years ago. It started with only 8,000 'founders', and it is still quite small.

In contrast, as Africa is the birthplace of modern humans, the African populations we looked at have a larger effective population size, which means more people have contributed to the genetic diversity.

Although there is little evidence for a difference in the number of harmful mutations between human populations over the whole genome, the French-Canadian population had a larger proportion of harmful mutations in their genomic coldspots.

Many of these mutations were specific to the French-Canadian population: they were either rare variants which happened to be there in some of the 8,000 population founders, or they have originated for the first time since the founding of Quebec 400 years ago.

We found similar results for the Finnish and Tuscan Italian population we looked at.

So we think that the population history of a group of people can also have an effect on the pattern of harmful genetic variants.

OSB: Where is your research headed for the future?

JH: In this study, we ignored the X and Y sex chromosomes.

We know that the Y chromosome never recombines, and the X recombines only in females, so the patterns there are likely different and deserve further investigation.

We would also like to test the same theory in other mammals. The availability of recombination maps and large-scale population data in other primate species, for example, makes this possible in the near future.

An Oxford philosopher has continued a tradition going back to Plato by using a fictional conversation to explore questions about truth, falsity, knowledge and belief in a new book published this month. But unlike Plato, his book is set on a train.

Timothy Williamson, the Wykeham Professor at Logic at Oxford University, has written Tetralogue: I'm Right, You're Wrong, in which four people with radically different outlooks on the world meet on a train. At the start of the journey each is convinced that he or she is right, but then doubts creep in.

In an interview with Arts Blog, Professor Williamson explains his hope that Tetralogue will give a wider audience an insight into the academic philosophy..

Q: What is the aim of the book?

A: Its starting point is the occurrence of radical disagreement, about science, religion, politics, morality, art, whatever. In contemporary society, many people are reluctant to apply ideas of truth and falsity, or knowledge and ignorance, to such clashes in point of view, because they are afraid of being dogmatic and intolerant. But can one really abstain from such distinctions without losing one's own point of view altogether? In a light-hearted way, the book aims to provide readers with the means to think more carefully and critically about such matters, and to avoid common traps and confusions.

Q: Who is your target audience?

A: The book is aimed primarily at people who haven’t studied philosophy academically, but who are interested in philosophical issues like those just mentioned. It might be someone who has been led to worry about them through personal experience of such clashes, or who has trouble handling them in their own research or teaching, or a teenager wondering what it would be like to study philosophy at university. I hope that even academic philosophers may find something to amuse them in it.

Q: What do you hope people take away from the book?

A: I’d like them to take away a nose for when certain fallacies are being committed or certain glib, problematic assumptions are being made. More constructively, I’d like to have empowered them to reason more logically about the sort of difficult issue I’ve mentioned. I also hope that they will have gained a sharper sense of the cut-and-thrust of philosophical argument, but also of the limited power of reason to force anyone to change their mind.

Q: Was it difficult to present philosophical concepts in ordinary dialogue on a train?

A: You find yourself sitting next to strangers on a train for several hours: a chance for a long talk. If Hitchcock is directing the film, the conversation turns to murder. If I’m writing the book, it turns to philosophy. Both are dangerous subjects with roots in ordinary life. Both need to be introduced carefully, because you can’t take much for granted about your audience. You have to start from the beginning. I must admit, when I’m on a train, I rarely speak to strangers, but I often listen in to their conversations. I’d love to hear them discuss murder, or philosophy.

Oxford University Press is publishing the book and will be holding Q&A sessions on Twitter in March. OUP has released an extract of the book, which we have reproduced below.

Sarah: It’s pointless arguing with you. Nothing will shake your faith in witchcraft!

Bob: Will anything shake your faith in modern science?

Zac: Excuse me, folks, for butting in: sitting here, I couldn’t help overhearing your conversation. You both seem to be getting quite upset. Perhaps I can help. If I may say so, each of you is taking the superior attitude ‘I’m right and you’re wrong’ toward the other.

Sarah: But I am right and he is wrong.

Bob: No. I’m right and she’s wrong.

Zac: There, you see: deadlock. My guess is, it’s becoming obvious to both of you that neither of you can definitively prove the other wrong.

Sarah: Maybe not right here and now on this train, but just wait and see how science develops—people who try to put limits to what it can achieve usually end up with egg on their face.

Bob: Just you wait and see what it’s like to be the victim of a spell. People who try to put limits to what witchcraft can do end up with much worse than egg on their face.

Zac: But isn’t each of you quite right, from your own point of view? What you—

Sarah: Sarah.

Zac: Pleased to meet you, Sarah. I’m Zac, by the way. What Sarah is saying makes perfect sense from the point of view of modern science. And what you—

Bob: Bob.

Zac: Pleased to meet you, Bob. What Bob is saying makes perfect sense from the point of view of traditional witchcraft. Modern science and traditional witchcraft are different points of view, but each of them is valid on its own terms. They are equally intelligible.

Sarah: They may be equally intelligible, but they aren’t equally true.

Zac: ‘True’: that’s a very dangerous word, Sarah. When you are enjoying the view of the lovely countryside through this window, do you insist that you are seeing right, and people looking through the windows on the other side of the train are seeing wrong?

Sarah: Of course not, but it’s not a fair comparison.

Zac: Why not, Sarah?

Sarah: We see different things through the windows because we are looking in different directions. But modern science and traditional witchcraft ideas are looking at the same world and say incompatible things about it, for instance about what caused Bob’s wall to collapse. If one side is right, the other is wrong.

Zac: Sarah, it’s you who make them incompatible by insisting that someone must be right and someone must be wrong. That sort of judgemental talk comes from the idea that we can adopt the point of view of a God, standing in judgement over everyone else. But we are all just human beings. We can’t make definitive judgements of right and wrong like that about each other.

Sarah: But aren’t you, Zac, saying that Bob and I were both wrong to assume there are right and wrong answers on modern science versus witchcraft, and that you are right to say there are no such right and wrong answers? In fact, aren’t you contradicting yourself?

Today, at an event in London, the government has revealed the outcome of a review of UK regulations for driverless cars as well as the launch of trial projects in three locations.

Today is also the first chance to see prototype driverless LUTZ Pathfinder pods built for one of the trials being driven around pedestrianized areas in Milton Keynes.

The Mobile Robotics Group (MRG) at Oxford University's Department of Engineering Science is involved in both announcements and has been at the forefront of autonomous vehicle research in the UK for over a decade, here's a brief run-down of what you need to know:

1. Oxford tech is in the LUTZ driverless pods

Technology developed at Oxford University's Mobile Robotics Group (MRG) is at the heart of the LUTZ Pathfinder pods. It enables the pods to navigate and understand their environment, so knowing exactly where they are on a pavement or pathway and being able to recognise and avoid pedestrians and obstacles. The Oxford team will be working with the Transport Systems Catapult (TSC) and project partners over the coming months to build autonomous systems into the pods, eventually doing away with the need for a steering wheel or human driver.

2. Wildcat shows off early tech back in 2011

The Oxford researchers first showed off their autonomous technology in March 2011 installed in a Bowler Wildcat 4X4 built by BAE Systems. Data gathered from cameras and lasers mounted on the Wildcat could be processed on board fast enough to be used in navigation and it was demonstrated driving around Begbroke Science Park, near Oxford. Coming only a year after Google announced it was testing driverless vehicles on California roads the Wildcat was a trail-blazer for autonomous vehicle research in the UK.

3. Does not rely on GPS to navigate

Oxford's autonomous vehicle tech does not rely on GPS to navigate because GPS doesn't work well in built-up environments and is in any case not precise or reliable enough to give an exact location. Neither does the Oxford approach use embedded infrastructure such as beacons and guide wires, which often guides robots in factories, as this would be impractical and far too expensive for use in most environments.

Instead the Oxford approach to navigation uses algorithms that combine machine learning and probabilistic inference to build up maps of the world around it using data form on-board sensors and 'learn as it drives'. The maps it builds (and updates) are like memories of a route which can be accessed to allow the vehicle to guide itself through places it has been before.

4. Robot Car demonstrated in 2014

February 2014 saw the first public demonstration of the Oxford Robot Car: Oxford University technology installed in a modified Nissan Leaf electric car that enables the vehicle to drive itself for stretches of a route. Robot Car was shown driving autonomously around private roads at Begbroke Science Park with the driver able to take his/her hands off the wheel as the car steered itself and stopped when confronted with an obstacle, such as a pedestrian walking out into the road.

The technology is controlled from an iPad on the dashboard which flashes up a prompt offering the driver the option of the car taking over for a portion of a familiar route – touching the screen then switches to 'auto drive' where the robotic system takes over. At any time a tap on the brake pedal returns control to the human driver.

For a long time Robot Car was the only autonomous vehicle in the UK with permission to go on public roads and the team's work in collaboration with the Department for Transport fed into the government's legislative review. Development of the Oxford Robot Car continues alongside the technology for the LUTZ pods and the team's other robotics research .

5. Blueprint for a low-cost system

One key aim of the Oxford research is to produce autonomous systems that are affordable and would be relatively simple to build into ordinary vehicles. The approach is made possible by advances in 3D laser-mapping that enable a system to rapidly build up a detailed picture of its surroundings. The 2014 Robot Car demonstration showed that the combination of this laser-mapping, cameras, and the team's clever software, can enable a vehicle to learn to navigate a route and know exactly where it is on the road. The system used for the demonstration was estimated to cost around £5000 but the team believe that systems that deliver limited autonomy – driving you 'some of the time in some of the places' – could eventually cost around £100.

6. Robot Car is being tested around Oxford

What does the world look like to a driverless car? As Oxford researchers continue to develop all the components needed for a complete system to drive itself on the public road the team has released new videos from tests around Oxford. The videos show how some of Oxford's most iconic locations – including the Sheldonian Theatre on Broad Street – are mapped and interpreted by the technology. The footage also shows how the system detects people and other traffic.

7. Self-driving or driverless?

Whilst the ultimate vision is for a car to drive itself without the need for any intervention from a human driver there are likely to be many stages on the road to fully autonomous vehicles. During the 2014 tests of Robot Car a trained human driver was behind the wheel at all times to take over control whenever necessary and this is also true of all current testing – in this sense they are not yet 'driverless'. Initial autonomous systems for cars are likely to be able to drive 'some of the places some of the time' offering to take over familiar routes such as the school run or daily commute. However, systems for vehicles such as the LUTZ pods that are designed to drive at lower speeds in less hazardous pedestrianized environments, may be able to achieve full 'end to end' autonomy sooner, doing away with the need for a driver altogether.

8. It’s not just about driverless cars…

Driverless cars may hog the headlines but the same Oxford University technology in both the LUTZ pods and Oxford Robot Car has many other applications. Current MRG projects include robotic survey systems for roads and railways and robotic rovers for use on other planets. In November 2014 Professor Ingmar Posner and Professor Paul Newman, leaders of the Oxford Mobile Robotics Group (MRG) founded a new spin-out firm, Oxbotica, to commercialise MRG's robotics and autonomous systems technologies.

Cyclic changes in the tilt of the Earth's axis and the eccentricity of its orbit have left their mark on hills deep under the ocean, a study published in Science has found.

These variations in the Earth’s position affect its climate; in particular, they drive glacial cycles.

The study demonstrated that sea level changes caused by the formation and melting of continental ice sheets have affected undersea volcanic processes that pattern the sea floor.

I talked to one of the study authors, Professor Richard Katz at Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences, about fire, ice and sea-sickness.

OxSciBlog: What was new about your study?

Richard Katz: My coauthors went out in a Korean research ship to an area known as the Australian-Antarctic ridge, in the Southern Ocean between Australia and Antarctica.

I am not a sailor, so I didn't go along!

From the ship, they were able to reconstruct very detailed maps of the ocean floor from using sonar echoes.

It has long been known that the Earth’s magnetic field has reversed occasionally in its history; the timing of these reversals is known, and their positions are recorded in the sea floor as it moves away from the mid-ocean ridge. So we were able to calculate the age of the features we were looking at.

The area that we were looking at, the Australian-Antarctic ridge, is an underwater mountain range, formed by magma rising up as the mantle beneath the Earth's crust melts. We built up a map of all the features (such as hills running for hundreds of kilometres along the ridge) that are formed by eruption of magma onto the sea floor as the plates spread apart.

At mid-ocean ridges, mantle melting is caused by de-pressurisation of the mantle.

OSB: What affects the pressure on the mantle, and therefore its melting rate?

RK: The most important thing affecting the pressure on the mantle is the amount of rock and water above it. When sea level changes, the weight of water pushing downward changes, and so the pressure changes.

So we were interested in episodes of glacier formation and destruction, since these can change sea water levels by as much as 100 metres: during ice ages, large amounts of water are taken out of oceans and frozen in continental glaciers, called ice sheets. So sea levels can drop drastically, and there is a reduction of pressure on the mantle beneath the sea floor. This means that mantle melting speeds up.

Conversely, as glaciers melt with the retreat of ice ages, sea levels rise, the pressure on the sea floor mantle rises, and there is less melting in the mantle below. More or less mantle melting means more or less volcanic activity, and since this volcanic activity creates the oceanic crust, it also means thicker or thinner crust. The variations in crust are what we measured from the ship.

OSB: So what factors modulate the advent and retreat of ice ages?

RK: One factor is the amount of the sun’s radiation falling on Earth. There are periodic variations in the Earth's orbit and tilt – the so-called Milankovitch cycles – which alter the amount of the Sun's heat reaching the earth. We know that these variations have paced ice ages on Earth over the past two million years.

Using a mathematical technique called spectral analysis, we found that the hills running along the Australian-Antarctic ridge have been laid down in periodic patterns that bear the fingerprint of the 23,000, 41,000 and 100,000-year Milankovitch cycles.

We also developed computational models that took into account sea-level changes, as well other factors (such as how long the magma takes to rise from the mantle to the volcano) which had been ignored by other models. This was the second big advance in our paper.

The results from our model are a good, quantitative fit to the actual measurements from the sonar.

OSB: Are the effects of man-made climate change on glacier melting and sea level rise likely to affect these processes?

RK: The effects that we're looking at are caused by sea level changes of 100 metres or more. This is what happens when the Earth transitions between an ice age and an interglacial period. But we are currently in an interglacial period.

Man-made climate change is likely to change sea level on the order of 10 metres in the coming centuries. Depending on how fast this change happens, it could affect mantle melting.

But that's still very small compared to the sort of changes that happened during the transition from an ice-age to a warmer climate. So man-made climate change is unlikely to have a measurable effect on the undersea volcanic processes that we are looking at.

OSB: You've shown that long-term climate affects volcanism. Does this work the other way around too: can volcanic activity feedback onto climate?

RK: It's an intriguing possibility, since there is about 10,000 times more carbon dioxide locked away inside the Earth, compared to the combined amount in the atmosphere and the oceans.

We know that long (over tens of thousands to millions of years of years) periods of volcanic activity are associated with higher temperatures, because volcanoes release this carbon dioxide which had otherwise been locked away, a process called volcanic degassing.

However, nobody has shown that glacial cycles are related to volcanic degassing. We think that this is possible, and this is a research question that we're actively pursuing.

OSB: What other future work are you planning?

RK: We'd really like data from other ridges in the middle of oceans: these results are from measurement from just one. But if this is a general process, as we think, that the fingerprints of glacial cycle changes should be visible in other mid-ocean ridges too.

The problem is that it is very expensive to go out to the sea and make these measurements, so the opportunity doesn't arise very often.

We're fortunate to have had funding from the US National Science Foundation to make measurements of the Juan de Fuca ridge in the Pacific last year. We hope that analysing this data will support the ideas that we have put forward in this paper.

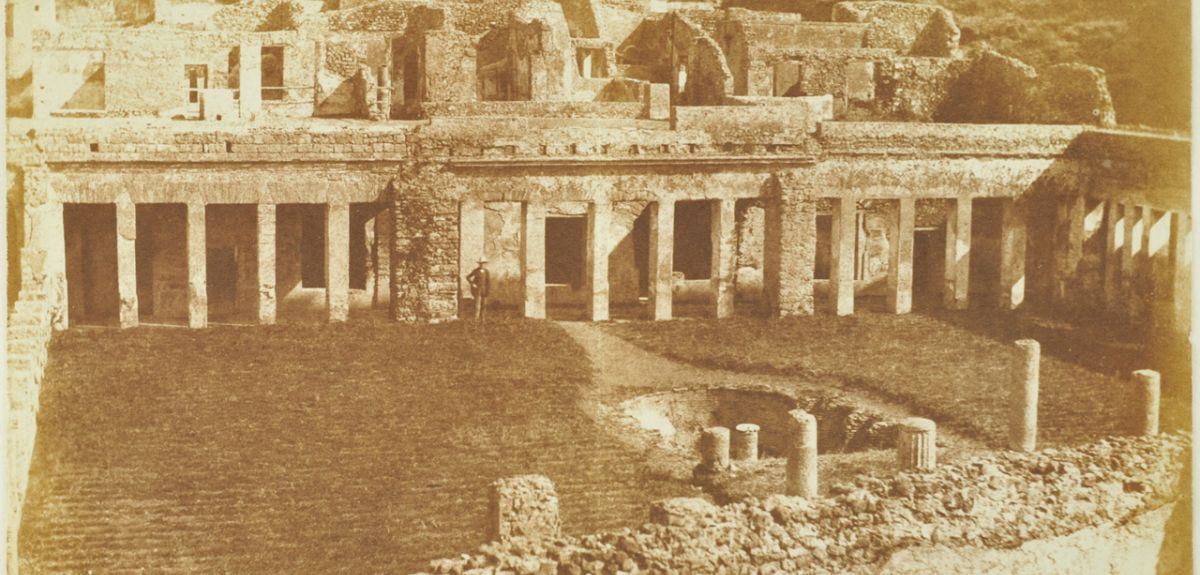

William Henry Fox Talbot is best-known today as a Victorian pioneer of photography. But an Oxford researcher has revealed that, for Talbot, photography was a means to an end in deciphering some of the oldest writing in human history.

Talbot's "calotype" process is a direct ancestor of modern imaging technology, and his family archive was acquired by the Bodleian Library last year.

"What's not so well-known about Talbot is that he only photographed for about ten years of his life," said Dr Mirjam Brusius, of the Department of the History of Art at Oxford University. "He worked in optics, botany, politics and other areas. In fact, he developed his photographic process in part to help decipher Mesopotamian artefacts.

"He was drawn to what was difficult and obscure. When he worked in botany, he was interested in mosses, because they're very hard to classify and identify. When he first became interested in antiquity, he worked briefly on Egyptian hieroglyphs - but they were too easy, they had already been largely deciphered, so he moved on to Assyrian tablets, and the cuneiform which was not so well understood. Talbot saw the tablets as a kind of mathematical exercise. He wasn't so interested in their content."

Cuneiform is one of the most ancient writing systems to survive in the world, dating back as far as 3000 BC. Knowledge of the system was completely lost until 19th-century Western archaeologists began to uncover clay tablets while excavating in the Middle East.

"Talbot spent a lot of time trying to propagate interest in photography as a tool for archaeological research," said Dr Brusius. "He put in a huge amount of energy but people were happy to use their existing tools, such as drawing. He did his best to convince the British Museum to take a camera on their expeditions, but the chemicals, the heavy equipment and changeable conditions meant they were not keen.

"Even in 1852, ten years after his invention of the calotype, he was still trying to persuade them to use a camera in the museum, to record the artefacts. He was lucky enough to know Lord Rosse [whom we've covered in a previous Arts Blog]. Rosse was a trustee at the British Museum and put in a good word for him, and the museum eventually hired a freelance photographer. The cuneiform collection was photographed, and Talbot hoped to use the resulting images in his research.

"Unfortunately for him, there was a certain amount of rivalry between him and the professional Assyriologists. Talbot was a wealthy gentleman who did not need to work and they considered him an amateur. Henry Rawlinson, a diplomat, was a major figure in the field. He worked out that Talbot was quite good, and didn't want him to be the first to decipher the inscriptions. Rawlinson's Assyriology was essentially a political enterprise, and there were British imperialist interests at play in the Middle East which were somewhat at odds with Talbot's 'armchair science'. So Talbot did not get the photos at first.

"These were inscriptions which could confirm or disprove the historical accuracy of the Bible. Artefacts might be suppressed if they challenged the prevailing narrative: one tablet contained an account of a flood which was at odds with the biblical story. The authority of the Bible as a historical source was seriously contested, and at a time when religious authority was being challenged in a variety of ways by natural science, this was very significant.

"Working in the Talbot archive at the British Library, I found his handwriting on one of the British Museum photographs. It seems that after another nine years, in about the early 1860s, Talbot finally received the photographs. His relationship with the professional Assyriologists gradually improved, along with his reputation and respect, and he was a founding member of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. They had perhaps come to realise that they needed people like Talbot, as much as he needed their contacts and equipment."

- ‹ previous

- 154 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria